The rivers of New Zealand are used for a variety of purposes and face a number of environmental issues. In the North Island's hill country the rivers are deep, fast flowing and most are unnavigable. Many of the rivers in the South Island are braided rivers. The navigable rivers were used for mass transport in the early history of New Zealand.

Statistics

The longest river in New Zealand is the Waikato River with a length of 425 kilometres (264 miles). The largest river by rate of flow is the Clutha River / Mata-Au with a mean discharge of 613 cubic metres per second (21,600 cu ft/s).[1] The shortest river is claimed to be the Tūranganui River in Gisborne at 1,200 metres (3,900 feet) long.[2]

Some of the rivers, especially those with wide flood plains and stop banks, have long road bridges spanning them. The Rakaia River is crossed by Rakaia Bridge, the longest bridge in New Zealand at 1,757 m (5,764 ft). The third longest bridge is the Whirokino Trestle Bridge on State Highway 1 crossing the Manawatū River.[3]

Over 180,000 km (110,000 mi) of rivers have been mapped in New Zealand.[4]

Uses

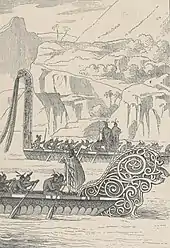

Before colonisation, Māori frequently used the navigable rivers (waterways) for transportation. Waka (canoes) made of hollowed-out logs were the main mode of navigating rivers.[5] During the early European settler years, coastal shipping was one of the main methods of transportation.[6] There are 1,609 km (1,000 mi) of navigable inland waterways; however these are no longer significant transport routes.

Rivers are used for commercial tourism and recreation activities such as rafting, canoeing, kayaking and jet-boating. Bungy jumping, pioneered as a commercial venture by a New Zealand innovator, is often done above some of the more scenic rivers.

Over half of the electricity generated in New Zealand is hydroelectric power.[7] Hydroelectric power stations have been constructed on many rivers, some of which dam the river completely while others channel a portion of the water through the power station. Some of the large hydroelectric power schemes in both North Island and South Island use a system of canals to move water between catchments in order to maximise electricity generation.

Conservation and pollution

River conservation is threatened by pollution inflows from point and non-point sources. In the past rivers had been used for pollution discharges from factories and municipal sewerage plants. With increasing environmental awareness and the passing of the Resource Management Act 1991, these sources of pollution are now less problematic. Water abstraction, especially for irrigation, is now a major threat to the character of rivers. An upsurge in conversion of land to dairy farming is stretching water resources. Also, since dairy farming is becoming more intensified in New Zealand and requires large amounts of water, the problem is therefore being exacerbated.

Acid mine drainage (AMD) from the Stockton coal mine has altered the ecology of the Mangatini Stream on the West Coast. The Stockton mine is also leaching AMD into the Waimangaroa River and the proposed Cypress Mine will increase this amount.

There is a high level of pollution in lowland rivers and streams that flow through urban or pastoral farming areas.[8]

A report[9] from the Ministry of Economic Development identified a large number of rivers as being suitable for hydroelectric power production. This report alarmed the Green Party and a number of environmental organisations due to the fear of an increasing loss of scenic rivers and rivers that have a high degree of natural character.

See also

References

- ↑ Murray, D. L. (1975). "Regional hydrology of the Clutha River". Journal of Hydrology (N.Z.). 14 (2): 85–98.

- ↑ "Gisborne Region Environmental Reporting". Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (LAWA). Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "FAQs". Transit New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008.

- ↑ Young, David (1 March 2009). "Rivers – How New Zealand rivers are formed". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatu- Taonga. ISBN 978-0-478-18451-8. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ↑ Young, David (24 September 2007). "Rivers – Māori and rivers". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ↑ New Zealand's Burning: Overview of coastal shipping 1885 – Arnold, Rollo, Victoria Press, Victoria University of Wellington, 1994

- ↑ Kelly, Geoff (June 2011). "History and potential of renewable energy development in New Zealand". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 15 (5): 2501–2509. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.01.021.

- ↑ Scott T. Larned; Mike R. Scarsbrook; Ton H. Snelder; Ned J. Norton; Barry J. F. Biggs (2004). "Water quality in low-elevation streams and rivers of New Zealand: Recent state and trends in contrasting land‐cover classes". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. The Royal Society of New Zealand. 38: 347–366. doi:10.1080/00288330.2004.9517243.

- ↑ East Harbour Management Services (January 2004). "Identification of Potential Hydroelectric Resources". Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Government of New Zealand. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

Further reading

- Knight, Catherine (2016). New Zealand's Rivers: An Environmental History. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press. ISBN 978-1-927145-76-0.

- Mosley, M Paul, ed. (1992). Waters of New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Hydrological Society. ISBN 0-473-01667-2.

- Egarr, Graham; Jan Egarr; John Mackay. 64 New Zealand rivers: a scenic evaluation. Auckland: New Zealand Canoeing Association.

- Collier, K.J.; Clapcott, J.E.; Young, R.G. (August 2009). Influence of Human Pressures on Large River Structure and Function (PDF). CBER Contract Report 95. Centre for Biodiversity and Ecology Research.

External links

- National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research – National Centre for Water Resources

- Wild Rivers – a campaign to protect rivers

- Whitewater NZ (formerly New Zealand Recreational Canoeing Association)

- Ministry for the Environment – water information page

- League table of the suitability of New Zealand rivers for contact recreation from NIWA