Richard Scott | |

|---|---|

| Born | baptized 9 September 1605 |

| Died | by 1 July 1679 |

| Education | signed his name to documents |

| Occupation | Shoemaker |

| Spouse | Katharine Marbury |

| Children | James, John, Mary, Joseph, Patience, Hannah, Deliverance |

| Parent(s) | Edward Scott and Sarah Carter |

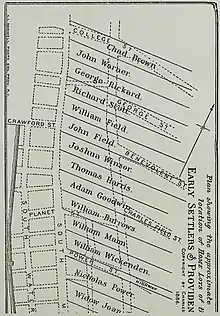

Richard Scott (1605–1679) was an early settler of Providence Plantations in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He married Katherine Marbury, the daughter of Reverend Francis Marbury and sister of Puritan dissident Anne Hutchinson. The couple emigrated from Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire, England with an infant child to the Massachusetts Bay Colony where he joined the Boston church in August 1634. By 1637, he was in Providence signing an agreement, and he and his wife both became Baptists for a time. By the mid-1650s, the Quaker religion had taken hold on Rhode Island, and Scott became the first Quaker in Providence.

Life

Richard Scott was born 1607 in Glemsford, Suffolk, England, the son of clothier Edward Scott of Glemsford.[1] Records are lacking concerning his childhood, but he appears as a young man in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire where he was married on 7 June 1632 to Katherine Marbury, the daughter of Francis Marbury and a younger sister of Anne Hutchinson.[2] The couple's first child was baptized in Berkhamsted in March 1634, and within months of this date the young family boarded a ship for New England.[3] John Austin suggests that they sailed on the Griffin,[4] but Robert Anderson rejects that hypothesis, stating that Scott was admitted to the Boston church on 28 August 1634 while the Griffin did not land until several weeks later.[3]

About August 1637, Scott was in Providence Plantations where he and 12 others signed an agreement submitting themselves to the collective agreements made for the public good.[5] This document was signed by Providence inhabitants who arrived too late to be included in an earlier division of lands, and by those who were minors during the earlier division.

Scott was not closely associated with the Antinomian Controversy surrounding his sister-in-law Anne Hutchinson in 1637 and 1638, as were most of Hutchinson's other relatives. However, he was present at her church trial in Boston on 15 March 1637/8, and he did speak briefly in her defense.[3] He experimented with non-Puritan religions, and his wife became a Baptist. Massachusetts governor John Winthrop reacted to this when he wrote in 1639, "at Providence things grew still worse: for a sister of Mrs. Hutchinson, the wife of one Scott, being infected with Anabaptistry… was re-baptized by one Holyman."[5] He went on to criticize the Baptists for denying infant baptism and having no magistrates.[3]

Difficulties as Quakers

Scott evidently accumulated a significant amount of land in Providence, since he paid more than three pounds in tax which was one of the highest amounts in the colony.[6] He appears on a 1655 list of freemen from Providence, and it is about this time that he and his wife became converts to the Quaker religion.[7] In September 1658, their future son-in-law Christopher Holder had his right ear cut off in Boston for his Quaker activism.[5] Katherine Scott was present and protested that "it was evident they were going to act the works of darkness, or else they would have brought them forth publicly and have declared their offences that all may hear and fear." She was committed to prison for saying this, and she was given "ten cruel stripes with a three fold corded knotted whip."[5] Scotts' daughter Patience went to Boston in June 1659, aged about 11, to witness against persecutions of Quakers, and she was sent to prison.[5] A short time later, their daughter Mary went to visit Christopher Holder in prison, and was herself apprehended and put in prison and kept there for a month.[7]

It appears that Katherine Scott drifted away from the Quaker religion by 1660, following a trip that she made to England. In September of that year, Roger Williams wrote a letter to John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay Colony in which he said, "Sir, my neighbor Mrs. Scott is come from England, and what the whip at Boston could not do, converse with friends in England, and their arguments, have in a great measure drawn her from the Quakers, and wholly from their meetings."[7] Williams waged a pamphlet war in the 1670s with Quaker founder George Fox. Williams did not agree with Quaker theology, and he published the pamphlet George Fox digged out of his Burrow in 1676, in response to which Fox published the pamphlet A New England Fire Brand Quenched in 1678.[8] Included in Fox's work was a letter from Scott which accused Williams of pride and folly, and charged him with "inconsistency in professing liberty of conscience, and yet persecuting those who did not join in his views."[8]

Richard Scott was dead by 1 July 1679 when his land was taxed.[8] His wife died in Newport on 2 May 1687, said to be aged 70 per the Rhode Island Vital Record, but this cannot be correct because her father had died by February 1611, so she could not have been born after 1611; therefore, she was at least 75 years old when she died.[2][5]

Family

Richard and Katharine Scott had seven known children. Mary married Quaker Christopher Holder and Hannah married colonial Rhode Island governor Walter Clarke, a son of earlier colonial president Jeremy Clarke and his wife Frances Latham.[8] Their grandson John Scott, Jr. married Elizabeth Wanton, who was a sister of colonial governors William Wanton and John Wanton.[9] Also, their grandson Sylvanus Scott, son of John, married Joanna Jenckes, the sister of colonial governor Joseph Jenckes.[10] Their descendant Sarah Scott married Stephen Hopkins, who was a governor and chief justice of the Rhode Island colony and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[11]

Ancestry of Richard Scott and Katharine Marbury

The ancestry of Richard Scott was summarized by G. Andrews Moriarty in 1944, referencing earlier works.[12] The ancestry of his wife, Katharine Marbury, was well documented by John Denison Champlin, Jr. in 1914.[13]

| Ancestors of Richard Scott (settler) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Anderson 2009, p. 204.

- 1 2 Anderson 2009, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson 2009, p. 206.

- ↑ Austin 1887, p. page needed.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Austin 1887, p. 272.

- ↑ Benedict Arnold paid the highest tax of five pounds.

- 1 2 3 Austin 1887, p. 274.

- 1 2 3 4 Austin 1887, p. 374.

- ↑ Austin 1887, pp. 215–6.

- ↑ Austin 1887, p. 113.

- ↑ Sanderson & Conrad 1846, p. 145.

- ↑ Moriarty 1944, p. 229.

- ↑ Champlin 1914, pp. 17–26.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert Charles (2009). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. VI R-S. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-225-1.

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Champlin, John Denison (1914). "The Ancestry of Anne Hutchinson". New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. New York: New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. XLV: 17–26.

- Moriarty, G. Andrews (April 1944). "Additions and Corrections to Austin's Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island". The American Genealogist. 20: 229–30.

- Richardson, Douglas (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. pp. 492–3. ISBN 0-8063-1750-7.

- Sanderson, John; Conrad, Robert Taylor (1846). Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia: Thomas, Cowperthwait & Company.

Stephen Hopkins.