| Quran |

|---|

|

Rasm (Arabic: رَسْم) is an Arabic writing script often used in the early centuries of Classical Arabic literature (7th century – early 11th century AD). Essentially it is the same as today's Arabic script except for the big difference that the Arabic diacritics are omitted. These diacritics include i'jam (إِعْجَام, ʾIʿjām), consonant pointing, and tashkil (تَشْكِيل, tashkīl), supplementary diacritics. The latter include the ḥarakāt (حَرَكَات) short vowel marks—singular: ḥarakah (حَرَكَة). As an example, in rasm, the five distinct letters ـبـ ـتـ ـثـ ـنـ ـيـ are indistinguishable because all the dots are omitted. Rasm is also known as Arabic skeleton script.

History

In the early Arabic manuscripts that survive today (physical manuscripts dated 7th and 8th centuries AD), one finds dots but "putting dots was in no case compulsory".[1] The very earliest manuscripts have some consonantal diacritics, though use them only sparingly.[2] Signs indicating short vowels and the hamzah are largely absent from Arabic orthography until the second/eighth century. One might assume that scribes would write these few diacritics in the most textually ambiguous places of the rasm, so as to make the Arabic text easier to read. However, many scholars have noticed that this is not the case. By focusing on the few diacritics that do appear in early manuscripts, Adam Bursi "situates early Qurʾān manuscripts within the context of other Arabic documents of the first/seventh century that exhibit similarly infrequent diacritics. Shared patterns in the usages of diacritics indicate that early Qurʾān manuscripts were produced by scribes relying upon very similar orthographic traditions to those that produced Arabic papyri and inscriptions of the first/seventh century." He concludes that Quranic scribes "neither 'left out' diacritics to leave the text open, nor 'added' more to clarify it, but in most cases simply wrote diacritics where they were accustomed to writing them by habit or convention."[3]

Rasm means 'drawing', 'outline', or 'pattern' in Arabic. When speaking of the Qur'an, it stands for the basic text made of the 18 letters without the Arabic diacritics which mark vowels (tashkīl) and disambiguate consonants (i‘jām).

Letters

The Rasm is the oldest part of the Arabic script; it has 18 elements, excluding the ligature of lām and alif. When isolated and in the final position, the 18 letters are visually distinct. However, in the initial and medial positions, certain letters that are distinct otherwise are not differentiated visually. This results in only 15 visually distinct glyphs each in the initial and medial positions.

| Name | Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | Rasm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | Code point | |||||

| ʾalif | ـا | ـا | ا | ا | ـا | ـا | ا | ا | U+0627 |

| Bāʾ | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب | ـٮ | ـٮـ | ٮـ | ٮ | U+066E |

| Tāʾ | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت | |||||

| Ṯāʾ | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث | |||||

| Nūn | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن | ـں | ـںـ | ںـ | ں | U+06BA[a] |

| Yāʾ | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي | ـى | ى | U+0649 | ||

| Alif maqṣūrah | ـى | ى | |||||||

| Ǧīm | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح | U+062D |

| Ḥāʾ | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح | |||||

| Ḫāʾ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ | |||||

| Dāl | ـد | ـد | د | د | ـد | ـد | د | د | U+062F |

| Ḏāl | ـذ | ـذ | ذ | ذ | |||||

| Rāʾ | ـر | ـر | ر | ر | ـر | ـر | ر | ر | U+0631 |

| Zāy | ـز | ـز | ز | ز | |||||

| Sīn | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س | U+0633 |

| Šīn | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش | |||||

| Ṣād | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص | U+0635 |

| Ḍād | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض | |||||

| Ṭāʾ | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط | U+0637 |

| Ẓāʾ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ | |||||

| ʿayn | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع | U+0639 |

| Ġayn | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ | |||||

| Fāʾ | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف | ـڡ | ـڡـ | ڡـ | ڡ | U+06A1 |

| Fāʾ (Maghrib) | ـڢ / ـڡ | ـڢـ | ڢـ | ڢ / ڡ | |||||

| Qāf | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق | ـٯ | ـٯـ | ٯـ | ٯ | U+066F |

| Qāf (Maghrib) | ـڧ / ـٯ | ـڧـ | ڧـ | ڧ / ٯ | |||||

| Kāf | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك | ـک | ـکـ | کـ | ک | U+06A9 |

| Lām | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل | U+0644 |

| Mīm | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م | U+0645 |

| Hāʾ | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه | U+0647 |

| Tāʾ marbūṭah | ـة | ة | |||||||

| Wāw | ـو | ـو | و | و | ـو | ـو | و | و | U+0648 |

| Hamzah | ء | ء | ء | ء | (None)[b] | ||||

- ^a This character may not display correctly in some fonts. The dot should not appear in all four positional forms and the initial and medial forms should join with following character. In other words the initial and medial forms should look exactly like those of a dotless bāʾ while the isolated and final forms should look like those of a dotless nūn.

- ^b There is no hamzah in rasm writing, including hamzah-on-the-line (i.e., hamzah between letters).

At the time when the i‘jām was optional, letters deliberately lacking the points of i‘jām: ⟨ح⟩ /ħ/, ⟨د⟩ /d/, ⟨ر⟩ /r/, ⟨س⟩ /s/, ⟨ص⟩ /sˤ/, ⟨ط⟩ /tˤ/, ⟨ع⟩ /ʕ/, ⟨ل⟩ /l/, ⟨ه⟩ /h/ — could be marked with a small v-shaped sign above or below the letter, or a semicircle, or a miniature of the letter itself (e.g. a small س to indicate that the letter in question is س and not ش), or one or several subscript dots, or a superscript hamza, or a superscript stroke.[4] These signs, collectively known as ‘alāmātu-l-ihmāl, are still occasionally used in modern Arabic calligraphy, either for their original purpose (i.e. marking letters without i‘jām), or often as purely decorative space-fillers. The small ک above the kāf in its final and isolated forms ⟨ك ـك⟩ was originally ‘alāmatu-l-ihmāl, but became a permanent part of the letter. Previously this sign could also appear above the medial form of kāf, instead of the stroke on its ascender.[5]

Examples

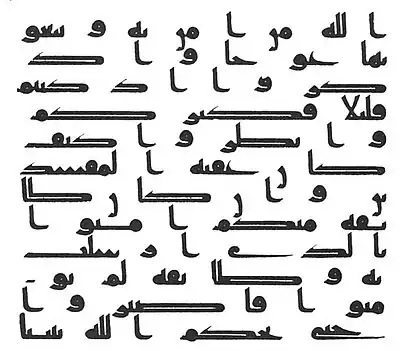

Among the historical examples of Rasm script are the Kufic Blue Qur'an and the Samarkand Qurʾan. The latter is written almost entirely in Kufic rasm.

The following is an example of Rasm from Surah Al-Aʿaraf (7), Ayahs 86 & 87, in the Samarkand Qur'an:

| Digital rasm with spaces | Digital rasm | Fully vocalized |

|---|---|---|

| ا لله مں ا مں ٮه و ٮٮعو | الله مں امں ٮه وٮٮعو | ٱللَّٰهِ مَنْ آمَنَ بِهِ وَتَبْغُو |

| ٮها عو حا و ا د | ٮها عوحا واد | نَهَا عِوَجًا وَٱذْ |

| کر و ا ا د کٮٮم | کروا اد کٮٮم | كُرُوا۟ إِذْ كُنْتُمْ |

| ڡلٮلا ڡکٮر کم | ڡلٮلا ڡکٮرکم | قَلِيلًا فَكَثَّرَكُمْ |

| و ا ٮطر وا کٮڡ | واٮطروا کٮڡ | وَٱنْظُرُوا۟ كَيْفَ |

| کا ں عڡٮه ا لمڡسد | کاں عڡٮه المڡسد | كَانَ عَٰقِبَةُ الْمُفْسِدِ |

| ٮں و ا ں کا ں طا | ٮں واں کاں طا | ينَ وَإِنْ كَانَ طَا |

| ٮڡه مٮکم ا مٮو ا | ٮڡه مٮکم امٮوا | ئِفَةٌ مِنْكُمْ آمَنُوا۟ |

| ٮالد ى ا ر سلٮ | ٮالدى ارسلٮ | بِٱلَّذِي أُرْسِلْتُ |

| ٮه و طا ٮڡه لم ٮو | ٮه وطاٮڡه لم ٮو | بِهِ وَطَائِفَةٌ لَمْ يُؤْ |

| مٮو ا ڡا صٮر و ا | مٮوا ڡاصٮروا | مِنُوا۟ فَٱصْبِرُوا۟ |

| حٮى ٮحکم ا لله ٮٮٮٮا | حٮى ٮحکم الله ٮٮٮٮا | حَتَّىٰ يَحْكُمَ ٱللَّٰهُ بَيْنَنَا |

Digital examples

| Description | Example |

|---|---|

| Rasm |

الاٮحدىه العرٮىه |

| Short vowel diacritics omitted. This is the style used for most modern secular documents. |

الأبجدية العربية |

| All diacritics. This style is used to show pronunciation unambiguously in dictionaries and modern Qurans. Alif Waṣlah (ٱ) is only used in Classical Arabic. |

ٱلْأَبْجَدِيَّة ٱلْعَرَبِيَّة |

| Transliteration | /alʔabd͡ʒadij:a alʕarabij:aʰ/ |

Compare the Basmala (Arabic: بَسْمَلَة), the beginning verse of the Qurʾān with all diacritics and with the rasm only. Note that when rasm is written with spaces, spaces do not only occur between words. Within a word, spaces also appear between adjacent letters that are not connected, and this type of rasm is old and not used lately.

| Rasm with spaces [c] |

ٮسم ا لله ا لر حمں ا لر حىم | |

|---|---|---|

| Rasm only [c] | ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم | |

| Iʿjām and all diacritics [c] |

بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ |  |

| Basmala Unicode character U+FDFD |

﷽ | |

| Transliteration | bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi | |

^c. The sentence may not display correctly in some fonts. It appears as it should if the full Arabic character set from the Arial font is installed; or one of the SIL International[6] fonts Scheherazade[7] or Lateef;[8] or Katibeh.[9]

Examples of Common Phrases

| Qurʾanic Arabic with Iʿjam | Qurʾanic Arabic Rasm | Phrase |

|---|---|---|

| بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ | ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم | In the name of God, the All-Merciful, the Especially-Merciful. |

| أَعُوذُ بِٱللَّٰهِ مِنَ ٱلشَّيْطَٰنِ ٱلرَّجِيمِ | اعود ٮالله مں السىطں الرحىم | I seek refuge in God from the pelted Satan. |

| أَعُوذُ بِٱللَّٰهِ ٱلسَّمِيعِ ٱلْعَلِيمِ مِنَ ٱلشَّيْطَٰنِ ٱلرَّجِيمِ | اعود ٮالله السمىع العلىم مں السىطں الرحىم | I seek refuge in God, the All-Hearing, the All-Knowing, from the pelted Satan. |

| ٱلسَّلَٰمُ عَلَيْکُمْ | السلم علىکم | Peace be upon you. |

| ٱلسَّلَٰمُ عَلَيْکُمْ وَرَحْمَتُ ٱللَّٰهِ وَبَرَکَٰتُهُ | السلم علىکم ورحمٮ الله وٮرکٮه | Peace be upon you, as well as the mercy of God and His blessings. |

| سُبْحَٰنَ ٱللَّٰهِ | سٮحں الله | Glorified is God. |

| ٱلْحَمْدُ لِلَّٰهِ | الحمد لله | All praise is due to God. |

| لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ | لا اله الا الله | There is no deity but God. |

| ٱللَّٰهُ أَکْبَرُ | الله اکٮر | God is greater [than everything]. |

| أَسْتَغْفِرُ ٱللَّٰهَ | اسٮعڡر الله | I seek the forgiveness of God. |

| أَسْتَغْفِرُ ٱللَّٰهَ رَبِّي وَأَتُوبُ إِلَيْهِ | اسٮعڡر الله رٮى واٮوٮ الىه | I seek the forgiveness of God and repent to Him. |

| سُبْحَٰنَکَ ٱللَّٰهُمَّ | سٮحںک اللهم | Glorified are you, O God. |

| سُبْحَٰنَ ٱللَّٰهِ وَبِحَمْدِهِ | سٮحں الله وٮحمده | Glorified is God and by His praise. |

| سُبْحَٰنَ رَبِّيَ ٱلْعَظِيمِ وَبِحَمْدِهِ | سٮحں رٮى العطىم وٮحمده | Glorified is my God, the Great, and by His praise. |

| سُبْحَٰنَ رَبِّيَ ٱلْأَعْلَىٰ وَبِحَمْدِهِ | سٮحں رٮى الاعلى وٮحمده | Glorified is my God, the Most High, and by His praise. |

| لَا حَوْلَ وَلَا قُوَّةَ إِلَّا بِٱللَّٰهِ ٱلْعَلِيِّ ٱلْعَظِيمِ | لا حول ولا ٯوه الا ٮالله العلى العطىم | There is no power no strength except from God, the Exalted, the Great. |

| لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا أَنْتَ سُبْحَٰنَکَ إِنِّي کُنْتُ مِنَ ٱلظَّٰلِمِينَ | لا اله الا اںٮ سٮحںک اںى کںٮ مں الطلمىں | There is no god except You, glorified are you! I have indeed been among the wrongdoers. |

| حَسْبُنَا ٱللَّٰهُ وَنِعْمَ ٱلْوَکِيلُ | حسٮںا الله وںعم الوکىل | God is sufficient for us, and He is an excellent Trustee. |

| إِنَّا لِلَّٰهِ وَإِنَّا إِلَيْهِ رَٰجِعُونَ | اںا لله واںا الىه رحعوں | Verily we belong to God, and verily to Him do we return. |

| مَا شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ کَانَ وَمَا لَمْ يَشَاءُ لَمْ يَکُنْ | ما سا الله کاں وما لم ىسا لم ىکں | What God wills will be, and what God does not will, will not be. |

| إِنْ شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ | اں سا الله | If God wills. |

| مَا شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ | ما سا الله | What God wills. |

| بِإِذْنِ ٱللَّٰهِ | ٮادں الله | By the permission of God. |

| جَزَاکَ ٱللَّٰهُ خَيْرًا | حراک الله حىرا | God reward you [with] goodness. |

| بَٰرَکَ ٱللَّٰهُ فِيکَ | ٮرک الله ڡىک | God bless you. |

| فِي سَبِيلِ ٱللَّٰهِ | ڡى سٮىل الله | On the path of God. |

| لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ | لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله | There is no deity but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God. |

| لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ عَلِيٌّ وَلِيُّ ٱللَّٰهِ | لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله على ولى الله | There is no deity but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God, Ali is the vicegerent of God. (Usually recited by Shia Muslims) |

| أَشْهَدُ أَنْ لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ | اسهد اں لا اله الا الله واسهد اں محمدا رسول الله | I bear witness that there is no deity but God, and I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God. |

| أَشْهَدُ أَنْ لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّ عَلِيًّا وَلِيُّ ٱللَّٰهِ | اسهد اں لا اله الا الله واسهد اں محمدا رسول الله واسهد اں علىا ولى الله | I bear witness that there is no deity but God, and I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God, and I bear witness that Ali is the vicegerent of God. (Usually recited by Shia Muslims) |

| ٱللَّٰهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَىٰ مُحَمَّدٍ وَآلِ مُحَمَّدٍ | اللهم صل على محمد وال محمد | O God, bless Muhammad and the Progeny of Muhammad. |

| ٱللَّٰهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَىٰ مُحَمَّدٍ وَآلِ مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَجِّلْ فَرَجَهُمْ وَٱلْعَنْ أَعْدَاءَهُمْ | اللهم صل على محمد وال محمد وعحل ڡرحهم والعں اعداهم | O God, bless Muhammad and the Progeny of Muhammad, and hasten their alleviation and curse their enemies. (Usually recited by Shia Muslims) |

| ٱللَّٰهُمَّ عَجِّلْ لِوَلِيِّکَ ٱلْفَرَجَ وَٱلْعَافِيَةَ وَٱلنَّصْرَ | اللهم عحل لولىک الڡرح والعاڡىه والںصر | O God, hasten the alleviation of your vicegerent (i.e. Imam Mahdi), and grant him vitality and victory. (Usually recited by Shia Muslims) |

| لَا سَيْفَ إِلَّا ذُو ٱلْفَقَارِ وَلَا فَتَىٰ إِلَّا عَلِيٌّ | لا سىڡ الا دو الڡٯار ولا ڡٮى الا على | There is no sword but the Zu al-Faqar, and there is no youth but Ali. (Usually recited by Shia Muslims) |

See also

- Kufic

- Abjad numerals

- History of the Arabic alphabet

- Qiraʾat

- Modern Arabic mathematical notation

- Book Pahlavi, an Iranian script with similar graphemic convergence.

References

- ↑ "What Are Those Few Dots for? Thoughts on the Orthography of the Qurra Papyri (709–710), the Khurasan Parchments (755–777) and the Inscription of the Jerusalem Dome of the Rock (692)", by Andreas Kaplony, year 2008 in journal Arabica volume 55 pages 91–101.

- ↑ Dutton, Yasin (2000). "Red Dots, Green Dots, Yellow Dots and Blue: Some Reflections on the Vocalisation of Early Qur'anic Manuscripts (Part II)". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 2 (1): 1–24. doi:10.3366/jqs.2000.2.1.1. JSTOR 25727969.

- ↑ Bursi, Adam (2018). "Connecting the Dots: Diacritics Scribal Culture, and the Quran". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 3: 111. doi:10.5913/jiqsa.3.2018.a005. hdl:1874/389663. JSTOR 10.5913/jiqsa.3.2018.a005. S2CID 216776083.

- ↑ Gacek, Adam (2009). "Unpointed letters". Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers. BRILL. p. 286. ISBN 978-90-04-17036-0.

- ↑ Gacek, Adam (1989). "Technical Practices and Recommendations Recorded by Classical and Post-Classical Arabic Scholars Concerning the Copying and Correction of Manuscripts" (PDF). In Déroche, François (ed.). Les manuscrits du Moyen-Orient: essais de codicologie et de paléographie. Actes du colloque d'Istanbul (Istanbul 26–29 mai 1986). p. 57 (§8. Diacritical marks and vowelisation).

- ↑ "Arabic Fonts". software.sil.org. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ "Google Fonts: Scheherazade". Google Fonts. Archived from the original on 2020-03-19. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ↑ "Google Fonts: Lateef". Google Fonts.

- ↑ "Google Fonts: Katibeh". Google Fonts.

External links

- Some pages from the famous Saint Petersburg-Samerkand-Tashkent Koran. The fourth to seventh images are written in the Kufic script

- A page in the earliest script Archived 2020-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, known as ma'il