Modern scholars of ancient Rome have found difficulty in defining who was considered to be living in poverty due to their lack of significant coverage in the historical record, and the difficulty in defining the lines between poverty and middle class. Roman writers describe the poorer parts of the population as unvirtuous and immoral masses who were threats to the nation and unconcerned with the values of the Roman world. Ancient Roman Christian depictions tend to depict the poor as more sympathetic and often call for the wealthy to help them. There were other efforts to help the poor, such as the Cura Annonae, a policy which redistributed grain. The Roman poor also had limited rights. They were unable to access political offices, had higher tax rates, and were unable to afford most status symbols.

Definition

It can be difficult to define ancient Roman poverty. The conditions of most people in the Roman world resembled modern ideas of poverty. They had high rates of infant mortality, poor diet, and low rates of literacy. Poverty was also not regarded as a problematic or unacceptable condition, which differs from the modern understanding of it. It is also unclear if there was a group of people which were noticeably poorer than other groups. Another possibility is that the Roman economy allowed civilians meeting the criteria for the modern understanding of poverty to not live a life resembling the modern understanding of poverty. Roman writers only make a distinction between the wealthy upper-class patricians and the rest of the population. They don't distinguish between the rest of the plebian class, and treat all of them as if they were a homogenous mass. Roman poverty can be defined by the lack of presence in the historical record. Archaeological evidence of poorer classes and people of low-status in ancient Rome is rare.[1]

The Roman Senate defined the groups known as the ordines. These were the equites, curiales, and the senators. The classes below these ones were known as the humiliores. It is unclear to what extent these classes were representative of economic inequality. They may have been political classes rather than economic ones.[2] Another uncertainty is the presence of a Roman middle class. Their society may have consisted of a handful of wealthy individuals which made up 0.6% of the population, an army that made up 0.4% of the population, and the poor masses that made up 99% of the populace. Other scholars, such as William Harris divided Roman society into three economic classes: those that relied on other's work, those that were well-off although they still worked, and the slaves and menial laborers. However, there is little archaeological evidence that can pinpoint who belonged to these classes. Scholars are also unsure if these views of Roman society are overly dichotomous, and if the real Roman economy was far more nuanced and complex.[3]

Social status and stigma

Wealth in ancient Rome was a status symbol, and many expensive objects, such as large houses were also status symbols.[4] In the Roman Republic political privileges were often restricted to the wealthy, although most rights and privileges were based on citizenship status, rather than economic status. The Roman military typically employed the poorer members of the Roman population. By the end of a campaign, the poverty-stricken populace was in a position to demand reforms or relief.[5] During earlier periods of Roman history the poor were considered to be virtuous and poverty was considered honorable. Stoic philosophers such as Seneca and Epicurus believed that poverty could lead to contentment with life and that increasing wealth did not reduce the problems a person suffered from, but merely altered it.[6] The Cynics believed poverty was a more desirable condition than wealth.[7][8]

By the late Republic, the poor were considered to be beneath others and to be lower in prestige and virtue than other social castes. Writers described them as incapable of any lasting virtue. They were considered to be a mass of peasants that was easily swayed and a threat to political stability.[9] Roman writers also considered the poor to only be concerned with "bread and circuses," rather than the intricacies and values of Roman society. Martial's epigrams compare the poor to dogs.[10] Roman cities and settlements were typically designed to geographically separate the living spaces of the rich from those of the poor. This social stigma likely reinforced the economic inequality and the social stratification present in ancient Rome. Wealthy Romans were terrified of poverty, and the humiliations and social ostracization that came along with it.[11][12] By the reign of Marcian in the 5th century poverty was no longer seen as shameful.[13]

Financial aid

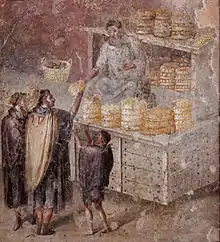

The Cura Annonae was a program to redistribute grain amongst the populace.[14][15] Cicero, a Roman politician and writer believed that generosity was a part of the human nature. Cicero, alongside the philosopher Seneca,[16][17] believed that all of the beneficiaries of this aid should be respectable members of the population with good moral character who would use the aid to try and escape poverty.[18][19][20] It was believed that many poor Romans were stuck in poverty due to their own moral faults, and to aid the poor would be a disservice to them. Roman writers described beggars dressed in rags spread throughout the streets asking for aid. They were said to be almost always elderly, and some were alleged to have blinded their own children to make them more sympathetic.[21][22] Other motivations for aiding the poor came from a fear of public humiliation or of being harmed in some way by the poor.[23] Despite these cultural beliefs, upper-class Romans were far more likely to help other members of the upper-class than they were to help poorer civilians.[24] Typically, philanthropists supporting the middle class or working class, as they were far more capable of benefiting the provider in return.[15] Certain groups did argue in favor of financial aid for the poor Such as the Cynics, Stoics, and Christians.[25]

Usually ancient Roman philanthropy was motivated by a desire to receive something in return.[26] Cicero and Seneca critiqued this in their works. They were disgusted at how people only gave when they expected they would receive something in return. It was common practice for people who had funded the construction of buildings to leave a marker stating that they had funded its construction. This practice was designed to boost the popularity and reputation of the benefactor. Who, due to their philanthropy, would have a statue be built of them in their honor. Philanthropic acts were important for presenting oneself as a generous and virtuous member of society. If a wealthy Roman did not participate in philanthropy they would bring dishonor onto their family.[15] Philanthropists were also motivated by a desire to gain political status. Patricians would provide services to the plebeians if the plebeians gave them support during elections. These services were legal defenses, supplies of material goods, and invitations to feasts.[27] Politicians would provide donations of food or money known as sportula in return for political support and the spreading of their good reputation.[28][29][30] Alongside the political benefits, the good reputation the wealthy would gather through these efforts allowed for them to gain favors from other wealthy Romans.[15]

Another way the wealthy would perform philanthropic acts was through the alimenta. It was a welfare program designed to aid orphans and poor children in Roman Italy.[31] The program was started by Nerva and funded by wealth gained through the Dacian wars, philanthropy, and taxation.[32] Although it was ended by Aurelian after his triumph.[33][34] The Cura Annonae was another program designed to aid the population of Rome.[14] It was a grain redistribution program that gave free or subsidized grain.[35]

Causes

The poor in Roman society had little or no access to land or property. Those who owned land were capable of using that land to generate more wealth or cultivate resources. Land was also the most common item used as security in loans. Poorer civilians were often relegated to working alongside slaves, although this provided an irregular source of income. Debt was another major factor that contributed to ancient Roman poverty. Loans usually had high interest rates and were required to be paid back under threat of harsh penalties. The Roman government imposed high rates of taxation on the poorer parts of the Roman population, while the wealthy paid little in taxes.[36] Poor Romans also faced difficulties finding jobs with adequate pay. It was extremely improbable for a worker to find enough work to properly support a family of three.[37]

Effects

.jpg.webp)

Poor Romans often sold themselves or their child into slavery. The disabled population of Rome had to rely on the goodwill of other people to survive. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman historian, the Roman poor lived in buildings' crevices, tabernae, or vaults beneath theaters or circuses.[38] They also lived in low-quality apartment buildings called insulae.[39] Poor Romans were especially vulnerable during crises, being vulnerable to food shortages or being the victims of crime.[40]

The poorest parts of the Roman population were unable to afford most forms of social interaction and demonstrations of status, such as baths, dinners, or collegia.[41] Poor Romans were barred from political positions and certain activities. Emperor Constantine enacted a law prohibiting unvirtuous women from marrying high-status men. Poor individuals in general were banned from marrying people above their social status. It was unclear if the poor belonged to this group. Roman law did not define the poor as a group. Poorer Romans were also buried in puticuli, which were mass burial sites.[42] It was also difficult for the poor to find jobs due to slavery. People would purchase slaves rather than pay workers.[43][44]

Christianity

Christians in ancient Rome sought to highlight the poorer members of Roman society and to bring attention to their struggles. John Chrysostom, a saint, a Church father, and the Archbishop of Constantinople argued that if the wealthy were to redistribute their wealth and fortune amongst the populace "you would have difficulty in finding one poor person for every fifty or even every hundred of the others." Paulinus' epistulae describe Christians organizing mass events designed to provide alms and gifts for the poor. However, it is possible he made this story up. Christian interpretations of the poor in ancient Rome didn't differentiate between differing groups of poor people. They depicted them as a homogenous mass in line with previous negative outlooks on those stuck in poverty. However Christian depictions did not portray poverty as immoral or unvirtuous. Augustine, a Catholic theologian, described beggars as immoral criminals who acted in unvirtuous ways and were far from God. However he also portrayed obsession with wealth and accruing money as like begging and only resulting in dissatisfaction with life. Augustine also believed that Jesus taught that people should aid beggars, and wrote that people should redirect their stigma from the poor, and towards the wealthy. Jesus himself was frequently associated with poverty.[45]

References

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 21-36.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 9-11.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 45-46.

- ↑ Edwards 1993, p. 151-154.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 8-9.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 13-15.

- ↑ Davies 2016.

- ↑ Campbell 2017, p. 1-3.

- ↑ Walker & Bantebya-Kyomuhendo 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Silver 2007, p. 225.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 183-184.

- 1 2 Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 9-10.

- 1 2 3 4 McCann 2012, p. 1-79.

- ↑ Kjær 2019, p. 121-159.

- ↑ Seneca & Stewart 1887.

- ↑ Cicero 2014, p. 41-45.

- ↑ Payton & Moody 2008, p. 140.

- ↑ Benthall 2012, p. 373.

- ↑ Seneca 1900, p. 6.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 39-40.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 74-75.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 39-40.

- ↑ Vallely 2020.

- ↑ Kjær 2019, p. 42-65.

- ↑ Aftyka 2019, p. 149-154.

- ↑ Sampley 2016, p. 178, 209–210.

- ↑ Faas 2005, p. 39-41.

- ↑ Hurschmann 2006.

- ↑ Ashley 1921, p. 5-16.

- ↑ Rich & Wallace-Hadrill 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Southern 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 1964, p. 123-146.

- ↑ Rickman 1980, p. 263.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 24-26.

- ↑ Neumeister 1993, p. 23.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Erdkamp 2013, p. 99.

- ↑ Morley 1998, p. 102.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Osborne & Atkins 2006, p. 130-144.

Bibliography

- Osborne, Robin; Atkins, Margaret, eds. (October 9, 2006), Poverty in the Roman World (1st ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482700, ISBN 978-0521106573, archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2022, retrieved August 4, 2022.

- Edwards, Catherine (1993), "Structures of immorality: Rhetoric, building, and social hierarchy", Politics of Immortality in ancient Rome (PDF), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (published February 26, 1993), doi:10.1017/CBO9780511518553, ISBN 978-051-151-855-3, archived from the original on August 8, 2022, retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Erdkamp, Paul, ed. (2013), The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (published September 30, 2013), doi:10.1017/CCO9781139025973, ISBN 978-113-902-597-3, archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2018, retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Neumeister, Christoff (1993), "Urban Culture in Ancient Rome", Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 2 (2): 21–37, JSTOR 43234745, retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Morley, Nevilel (1998), "Political Economy and Classical Antiquity", Journal of the History of Ideas, 59 (1): 95–114, doi:10.2307/3654056, JSTOR 3654056, retrieved August 8, 2022

- Silver, Moris (2007), "Roman Economic Growth and Living Standards: Perceptions Versus Evidence", Ancient Society, 37: 191–252, doi:10.2143/AS.37.0.2024038, JSTOR 44079897, retrieved August 8, 2022

- Harris, W.V. (February 3, 2011), Rome's Imperial Economy: Twelve Essays, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-161649-5, retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Cicero, Marcus (2014). "The Project Gutenberg eBook of De Officiis, by Cicero". gutenberg.org. Translated by Miller, Walter. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- Kjær, Lars (2019). The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition: Ideals and the Performance of Generosity in Medieval England, 1100–1300. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-42402-8.

- Seneca; Stewart, Aubrey (1887). On Benefits (De Beneficiis). Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- Benthall, Jonathan (August 20, 2012), Fassin, Didier (ed.), "Charity", A Companion to Moral Anthropology (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 359–375, doi:10.1002/9781118290620.ch20, ISBN 978-0-470-65645-7, retrieved August 27, 2022

- McCann, Genevieve I. (2012). Private Philanthropy and the Alimenta Programs in Imperial Rome (Thesis). Georgetown University.

- Vallely, Paul (September 17, 2020). Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-2013-3.

- Aftyka, Leszek (April 17, 2019). "Philanthropy in Ancient Times: Social and Educational Aspects". Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University. 6 (1): 149–154. doi:10.15330/jpnu.6.1.149-154. ISSN 2413-2349. S2CID 150861185.

- Sampley, J. Paul (October 6, 2016). Paul in the Greco-Roman World: A Handbook: Volume II. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 178, 209–210. ISBN 978-0-567-65707-7.

- Faas, Patrick (2005). Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome. University of Chicago Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-226-23347-5.

- Ashley, Alice M. (1921). "The 'Alimenta' of Nerva and His Successors". The English Historical Review. 36 (141): 5–16. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXXVI.CXLI.5. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 552639.

- Rich, John; Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (2003). City and Country in the Ancient World. ISBN 0-203-41870-0.

- Southern, Pat (2004). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. p. 123.

- Duncan-Jones, Richard (1964). "The Purpose and Organisation of the Alimenta". Papers of the British School at Rome. 32 (1): 123–146. doi:10.1017/S0068246200007261. ISSN 2045-239X. S2CID 155933416.

- Rickman, G.E. (1980). "The Grain Trade Under the Roman Empire". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 36: 263. doi:10.2307/4238709. JSTOR 4238709.. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Seneca (1900). Of Clemency (De Clementia), Book II.

- Davies, John (March 7, 2016). "wealth, attitudes to". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6880. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- Campbell, Charles S. (2017). "LEONIDAS OF TARENTUM AND CYNICISM - (M.) Solitario Leonidas of Tarentum. Between Cynical Polemic and Poetic Refinement. (Quaderni 19.) Pp. vi + 110. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2015. ISBN: 978-88-7140-607-7". The Classical Review. 67 (2): 368–370. doi:10.1017/S0009840X17000245. ISSN 0009-840X. S2CID 164336364.

- Walker, Robert; Bantebya-Kyomuhendo, Grace (2014). The Shame of Poverty. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968482-3.

- Payton, Robert L.; Moody, Michael P. (March 26, 2008). Understanding Philanthropy: Its Meaning and Mission. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00013-2.

- Hurschmann, Rolf (Hamburg) (October 1, 2006), "Sportula", Brill's New Pauly, Brill, archived from the original on August 27, 2022, retrieved August 27, 2022