| Porta Nuova | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Verona, Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°25′53.28″N 10°59′17.43″E / 45.4314667°N 10.9881750°E |

| Founded | 1532-1540 |

| Architect | Michele Sanmicheli |

Porta Nuova is a gateway to the historic center of Verona, built between 1532 and 1540. It was designed by architect Michele Sanmicheli. Giorgio Vasari said of the gateway in Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori "never before any other work of more grandeur or better design."[1][2]

History

Beginnings

Two resolutions of the Venetian Senate (the first on December 15, 1530, and the second on January 5, 1531) ordered the demolition of the long side of the wall that separated the Visconti Citadel from the rest of Verona, "for the convenience, and ornament of our city." At the same time, it was decided to renovate the country-side wall, since it had been severely damaged during the War of the League of Cambrai in 1516; such a project was certain to include the replacement of the medieval gate that stood near where Porta Nuova would later be built.[3]

Michele Sanmicheli was appointed engineer in charge of the fortifications of Verona ("inzener sopra le fabriche," as defined by the Serenissima).[4] The appointment took place in October 1530 but was not effective until May 1531. From that time, work on the military structures continued more expeditiously.[5] Sanmicheli's first intervention was the design of the bastion of the Holy Trinity, starting in the year following the beginning of his appointment, which was followed later by work on the bastions of Riformati, San Bernardino, San Zeno, Spagna, and San Francesco, as well as a series of intermediate artillery emplacements, including that of the cavalier of San Giuseppe.[6] This included the creation of three city gates: the first was Porta Nuova (1532), which was followed by Porta San Zeno (1541) and Porta Palio (1547).[4][6]

Urban framework

Porta Nuova, located between the bastion of the Holy Trinity and the bastion of Riformati, was built in conjunction with the realignment of the city walls between these two bastions[7] and the dismantling of the wall that divided the fortified Citadel from the rest of the city.[8] In this context Sanmicheli had the opportunity to fine-tune a new conception, from an urban planning point of view, of this large portion of the Venetian city, setting up as a focal point precisely Porta Nuova, which, compared to those built previously, introduced a radical novelty: it gave access to a long straight street (the street of Porta Nuova, which was built in 1535) that led directly, through the gates of Bra, to the Arena, near which Sanmicheli built the Honorij Palace a few years later.[8]

The project, therefore, had as its first objective the urban renewal of the city, a purpose that was even preeminent to military purposes. The architect, in fact, set himself the goal of accommodating the powerful dynamic thrust of the urban organism toward the south.[3] From a military point of view, he saw Porta Nuova as an element of Verona's southern city wall, and in function of it he prepared the two bastions located on its flanks, namely those of the Holy Trinity and the Riformati,[9] whereas from a civil point of view, the construction was to enhance the Arena and the revival of the Roman urbanistic scheme, based on orderly rectilinear axes, as opposed to the disorderly urbanism of the medieval period.[10] This scheme, which was intended symbolically to rediscover the Roman roots of the city, in practice promoted trade between the countryside and the area of Piazza Bra.[9]

Construction

Construction of the gate began in 1532 with work on the elevation toward the countryside, under the jurisdiction of podestà Giovanni Dolfin and captain Leonardo Giustinian, whose coats of arms can still be seen on the facade,[7] as recorded in 1571 by the report of captain Lorenzo Donato.[11] An inscription, which has disappeared, located above the attic, mentioned by Scipione Maffei in 1732 and by Francesco Ronzani in 1831, was dated 1533.[7][12][13] In 1535, therefore, the elevation toward the countryside, as well as the interior of the building, were nearly completed. All that was missing was the replica of the Lion of Saint Mark to be set above the attic, which was difficult to place in such a position because it was "very large and difficult to move," according to what was written in a report dated March 16 of that year.[7][14]

.JPG.webp)

Work on the creation of the façade toward Verona began in 1535, as evidenced by another inscription, now unreadable as it has been abraded, bearing the name of the architect and mentioned again by Maffei and Ronzani.[7] The podestà Cristoforo Morosini and the captain Giacomo Marcello (whose coats of arms are still visible on the facade) informed in their mandates about the completion of the building site around 1540.[15] The date 1540, moreover, is given by an inscription on the central tympanum of the elevation facing the city.[9][13] In the same year, when the elevation toward the city was nearly completed, the official opening of the gate took place, which a report dated July 26 of that year sets at August 1.[7][16]

The roofing of the gate, however, remained provisional for many years and is evidenced by two reports dated July 21, 1550[17] and 1564.[7][18] The roof was completed around 1570,[7] as can be inferred from a report by Captain Lorenzo Donato in 1571 that indicates it was completed.[18]

Nineteenth-century transformations

The lion of St. Mark was destroyed by the Jacobins in 1801 and later replaced by a sculpted group with a coat of arms bearing the double-headed imperial eagle in the center, later abraded, and topped by a crown.[19]

The current appearance of the monument, while not dissimilar to Sanmicheli's original one, has undergone other alterations as well, due to interventions that took place throughout the 19th century during the Austrian occupation, especially on the country-side façade. To this façade in 1852, in fact, two large lateral arches were added, with a rupture of the rhythm between the central portal and the two minor lateral ones;[1] a connecting corridor was also opened from the minor light on the right to the internal rooms and, on the front facing the city, the two rectangular openings placed on either side of the pediment were closed.[20] This intervention, which made a new addition to the original monument while remaining faithful to its design and construction technique, can be identified because of the "decidedly lower level" of the ashlar lining.[21]

To cope with the growth of civilian traffic, the right-hand fornix (in relation to the exterior façade) was opened in 1854, followed by the left-hand one in 1900, renovations that in this case included some demolition of the 16th-century structure. In the interior façade, in fact, the new openings replaced the windows of the side rooms,[19] originally intended for the guardhouse, to such an extent that the left room still retains a large fireplace.[22] On the same occasion, the double flight of internal stairs leading to the roof and artillery emplacements was demolished.[19]

The area in front of the gate, on the other hand, underwent significant transformations in the second half of the nineteenth century, particularly due to the expansion of the Verona Porta Nuova station. As the terminus of the city's tramway network, in operation between 1884 and 1951, the station required the passage of the line under the gate's arches to connect with the city center.[23] Beginning in 1866, with the annexation of the Veneto region to the Kingdom of Italy, the defensive function of the magistral wall was lost: under the Italian administration, therefore, several passages and breaches were made along the walls to facilitate traffic in and out of the city, including the two openings on either side of Porta Nuova.[24]

Description

Francesco Maria I Della Rovere, Captain General, wanted the gates to be located "in an open place and straight between two bastions," that they should not be " entangled and twisted" like those of Ferrara, and that in the center of the curtain between the two bastions there should be a cavalier suitable for the placement of artillery.[22]

The volume comprising the gate structure gave the impression of being an integral part of the walls, as it did not project beyond the curtain wall. Its height was also limited, so as to make it less vulnerable to enemy artillery hits. The block has two circular towers on either side, used by sentries and originally covered by a wooden roof with a tiled covering, the shape of which allowed an excellent view of the surrounding area. The uncovered top of the gate was used for the placement of fortress artillery, so that according to Scipione Maffei this would have been "the first example of making a gate to be used also as a Cavalier."[22] This explains the considerable width of the gate, necessary to maneuver the artillery, and the thickness of walls, pillars and the roof, necessary to support its weight and the vibrations of the cannonades.[25][26]

The plan, rectangular in shape, is laid out as an elaborate three-lane design, defined by four large pillars with dividing Doric pilasters. The side aisles provided access to guard posts, complete with fireplaces, and to small rooms that could be used as cells. The interior is almost entirely covered by ashlar.[27] The gate was accessible from the countryside by wooden drawbridges lowered over the fixed masonry bridge, which ran across the deep magisterial moat.[28]

.JPG.webp)

The building draws on some elements of Ancient Roman architecture, especially Verona's antiquities: the Arena, due to the use of the Doric order and ashlar;[29] the Arch of Jupiter Ammon (which stood between Corso Porta Borsari and Via Quattro Spade), the keystone of which, now in the Maffeian Lapidary Museum, is evoked through the use, in the keystone of the central arch of the main façade, of the deity's face, a symbol alluding to power, royalty, and strength;[30] and the older façade of Porta Leoni, evoked in the use of the running dog frieze.[31] These references, instrumental to the political program of the Venetian republic, which wanted to fortify and adorn the cities it controlled by drawing inspiration from the grandeur of ancient Rome,[19] merged firmly with the two practical functions of the building: to be an easy route of communication between the city and the countryside and to be part of the defensive system of the inhabited area.[9]

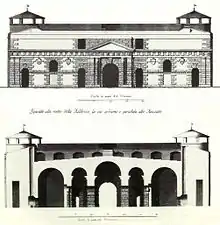

Elevations

The original elevation toward the countryside echoed the classical compositional scheme of the triumphal arch, but due to the massive forms and the ashlar that completely covered the gateway, it took on a more austere appearance. The façade is divided into a central part with the main portal, in which paired half-columns and lesenes support a tympanum, and two slightly set back side parts with small portals, to which two more large side arches were added in the 19th century. The attic floor supported the lion of St. Mark, later replaced by the sculpted group with two griffins, between which stood the coat of arms with the double-headed eagle, later abraded.[32]

This façade had a particularly massive and stocky Doric order, lacking a base, and a facing completely covered in rough ashlar, including the half-columns and pilasters, while the frieze, containing metopes and triglyphs, appears almost rough-hewn. The simultaneous use of Doric order and ashlar was not new, having already been used for several buildings of the same period as this one, but such a combination was also present in the Veronese amphitheater, right at the end of the new city course that was emerging. This juxtaposition of Doric order and ashlar gave the façade a character of indestructibility and strength, very suitable for a military architecture.[32]

The rear façade, on the city side, spans the entire length of the block: the central part faithfully reproduces its corresponding one on the front façade, while a sequence of three arched openings extends to the sides: the one closest to the end of the gateway gave access to the stairs; the middle one is a large archway accessible to vehicles, with a window originally illuminating the upper floor; finally, the last opening allowed access to the interior rooms of the structure. In this elevation, stone material combined with brick was used, a choice that gives the façade a less threatening appearance; moreover, while Red Verona marble was used in the front façade, less noble tuff was used for the one in the rear.[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Notiziario della Banca Popolare di Verona, Verona, 1984, n. 3.

- ↑ Vasari (1568, ch. Vita di Michele San Michele architettore veronese)

- 1 2 Puppi (1971, p. 24)

- 1 2 Conforti Calcagni (2005, p. 84)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 243)

- 1 2 Davies & Hemsoll (2004, pp. 243–244)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 244)

- 1 2 Brugnoli & Sandrini (1988, p. 121)

- 1 2 3 4 Puppi (1971, p. 27)

- ↑ Conforti Calcagni (2005, pp. 85–86)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 63)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 64)

- 1 2 Ronzani & Luciolli (1831, p. 2, vol. III)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 65)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 66)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 66: BCVe, Ms. Cod. Cicogna 2777)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 67: ASVe, Consiglio dei X, Lettere dei Rettori, b. 194, f. 54.)

- 1 2 Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 272, footnote 67)

- 1 2 3 4 Stocker, Pierre & Martinelli (2013, p. 107)

- ↑ Brugnoli & Sandrini (1988, p. 142, footnote 103)

- ↑ Conforti Calcagni (2005, p. 96)

- 1 2 3 Stocker, Pierre & Martinelli (2013, p. 106)

- ↑ Viviani (2008)

- ↑ Conforti Calcagni (2005, p. 110)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, pp. 246–247)

- ↑ Ronzani & Luciolli (1831, p. 1, vol. III)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 251)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 246)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 252)

- ↑ Concina & Molteni (2001, p. 131)

- ↑ Brugnoli & Sandrini (1988, pp. 121–123)

- 1 2 Davies & Hemsoll (2004, p. 247)

- ↑ Davies & Hemsoll (2004, pp. 250–251)

Bibliography

- Vasari, Giorgio (1568). Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri. Edizione Giuntina. part III, volume II.

- Brugnoli, Pierpaolo; Sandrini, Arturo (1988). Architettura a Verona nell'età della Serenissima. Vol. I. Verona: Banca Popolare di Verona. OCLC 311461716.

- Concina, Ennio; Molteni, Elisabetta (2001). La fabrica della fortezza: l'architettura militare di Venezia. Verona: Banca Popolare di Verona. OCLC 49401651.

- Conforti Calcagni, Annamaria (2005). Le mura di Verona. Cierre edizioni. ISBN 88-8314-008-7.

- Davies, Paul; Hemsoll, David (2004). Michele Sanmicheli. Mondadori Electa. ISBN 88-370-2804-0.

- Puppi, Lionello (1971). Michele Sanmicheli architetto di Verona. Padova: Marsilio. OCLC 825249.

- Ronzani, Francesco; Luciolli, Gerolamo (1831). Le fabbriche civili, ecclesiastiche e militari di Michele Sanmicheli, architetto veronese. Venice: Giuseppe Antonelli.

- Stocker, Mirjam; Pierre, Elodie; Martinelli, Chiara, eds. (2013). Un parco da vivere: guida al parco delle mura e dei forti di Verona. Legambiente.

- Viviani, Giuseppe Franco, ed. (2008). Verona 1908: arriva il tram elettrico (PDF). Verona: Associazione Filatelica Numismatica Scaligera. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2018.