Pierre André de Suffren | |

|---|---|

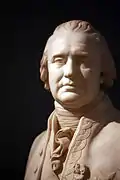

Bust of Suffren by Jean-Antoine Houdon | |

| Nickname(s) | Jupiter[1] |

| Born | 17 July 1729 Château de Saint-Cannat, France |

| Died | 8 December 1788 (aged 59) Paris, France |

| Buried | Ashes defiled in 1793 by the Revolutionaries[2] |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1743–1784 |

| Rank | Vice-admiral in the French Navy General of the Galley of Malta |

| Unit | Indian Ocean squadron |

| Battles/wars | War of the Austrian Succession: |

| Awards | Order of Saint-John of Jérusalem |

Admiral comte Pierre André de Suffren de Saint Tropez, bailli de Suffren [Note 1] (17 July 1729 – Paris, 8 December 1788[4]), Château de Saint-Cannat) was a French Navy officer and admiral. Beginning his career during the War of the Austrian Succession, he fought in the Seven Years' War, where he was taken prisoner at the Battle of Lagos. Promoted to captain in 1772, he was one of the aids of Admiral d'Estaing during the Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, notably taking part in the Siege of Savannah.

Suffren was then appointed to serve in the Indian Ocean under Thomas d'Estienne d'Orves, but assumed command himself at his death. Leading a 15-ship squadron, he fought five intense and evenly matched battles for control of the sea against Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Hughes. Through these battles, Suffren managed to secure French dominance of the seas in Indian waters until the conclusion of the war at the Treaty of Paris. At his return, he was promoted to vice-admiral. He died shortly before he was to take command of the Brest squadron of the French fleet.

Biography

Early life

Pierre André de Suffren was born on 17 July 1729 in the Château de Saint-Cannat to the family of Marquis Paul de Suffren, the third son of an old nobility from Provence with two daughters and three other sons.[5] [6] [Note 2] In October 1743, as the War of the Austrian Succession was raging, Suffren, aged 14,[5] went to Toulon to undertaken naval studies as a Garde-Marine.[4] However, he spent only 6 months ashore before he was appointed on a ship.[8]

War of the Austrian Succession

Suffren served on the 64-gun Solide[5] and took part in the Battle of Toulon in 1744. During the battle, Solide engaged HMS Northumberland. [9]

In the spring of 1745, Suffren transferred to Pauline, part of a 5-ship and 2-frigate squadron under Captain Jean-Baptiste Mac Nemara,[Note 3] sent to America to harass British forces.[10][11] At his return, Suffren served on the 60-gun Trident, under Captain d'Estourmel, and took part in the Duc d'Anville expedition.[12]

Suffren graduated from the Gardes-Marine in 1747 as an ensign,[4] and worked on commissioning the brand new 74-gun Monarque, under Captain La Bédoyère,[13] in a squadron under Des Herbiers de l'Estenduère.[14] He took part in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre on 25 October 1747, where La Bédoyère was killed and Monarque, badly damaged, was captured.[15] Suffren was taken prisoner.[16]

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle restoring peace, Suffren joined the Order of Malta.[17] He served in several commercial expeditions[18] on galleys of the order, escorting merchantmen and defending them against the depredation of the Barbary corsairs. In late 1754, Suffren departed Malta to return to Toulon.[17]

Seven Years' War

In 1756, Suffren had returned to Toulon and had risen to lieutenant. At the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, Suffren was appointed to the 64-gun Orphée, part of a 12-ship squadron under La Galissonière tasked with ferrying 12,000 men under Maréchal de Richelieu to strike Menorca. The squadron departed on 10 April, arriving on 17 and landing troops; the British garrison retreated to St. Philip's Castle and was forced to surrender after the Siege of Fort St Philip.[19] Patrolling between Menorca and Mallorca to prevent British relief to support Fort St. Philip, La Galissonière intercepted a 13-ship squadron under Admiral Byng, leading to the Battle of Minorca. The British failed to break the French blockade, and Fort St. Philip fell on 29 July.[20]

In 1757, Suffren transferred to the 80-gun Océan, flagship of a 6-ship and 2-frigate squadron under Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran. The squadron departed Toulon in November, bound for Brest. On 7 December, it called Cartagena to resupply, and found itself blockaded by a British from under Henry Osborne. [20] A relief squadron under Duquesne de Menneville attempted to break the blockade, but was destroyed in the Battle of Cartagena, as La Clue failed to sortie. Suffren witnessed the capture of Foudroyant and Orphée on 28 February 1758. La Clue's squadron eventually returned to Toulon.[21]

Toulon was blockaded by Edward Boscawen's forces but, on 16 August 1758, La Clue seized an opportunity to make a sortie with 12 ships and 3 frigates. The frigate HMS Gibraltar detected La Clue's squadron and reported to Boscawen, who moved to intercept.[22] Meanwhile, the French squadron failed to maintain formation and scattered.[23] In the ensuing Battle of Lagos, Océan ran aground in Almadora Bay and was burnt by the British, in violation of neutrality laws,[24][25] while her crew was taken prisoner, including Suffren.[26][18] He returned to France after several months and was left without employ at sea for several years.[27]

Interwar period

On the return of peace in 1763 Suffren intended again to do the service in the caravans which was required to qualify him to hold the high and lucrative posts of the order. He was, however, named to the command of the 20-gun xebec Caméléon,[27] which he cruised against the Barbary pirates.[11][28] Shortly thereafter, he transferred on Singe, also a 20-gun xebec, part of a squadron under Louis Charles du Chaffault de Besné.[28] He took part in the Larache expedition.[27] In 1767, Suffren was promoted to frigate captain and called to Brest to serve on the 64-gun Union, flagship of a squadron headed by Breugnon.[29][28] Upon his return, he was promoted to Frigate captain on 18 August 1767.[30]

After the end of the expedition, Suffren returned to Malta to resume escort duty with the order. He spent four years, rising from Knight to Commander. In February 1772, he was promoted to captain in the French Navy, and returned to Toulon to take command of the 26-gun frigate Mignonne. He conducted two patrols in the Eastern Mediterranean. [29][28]

In 1776, Duchaffault appointed Suffren to the command of the 26-gun frigate Alcmène. She departed for a training cruise to drill new navy officers.[29] From that time till the beginning of the War of American Independence he commanded vessels in the squadron of evolution which the French government had established for the purpose of training its officers. [11]

War of American independence

Tensions mounted between France and England in early 1778 in the context of the American Revolutionary War, with the action of 17 June 1778 constituting a step up announcing France's participation in the American Revolutionary War. Suffren was appointed to the fleet of Admiral d'Estaing, leading a division comprising the 64-gun Fantasque, which he personally captained,[25] and the frigates Aimable, Chimère and Engageante. [31] The mission of his force was to support Franco-American efforts in the Battle of Rhode Island by striking a 5-frigate British squadron anchored in Narragansett Bay, off Newport,[28] comprising HMS Juno, Flora, Lark, Orpheus and Cerebus. On 5 August 1778, Suffren entered the Bay and anchored next to the British, who cut their cables and scuttled their ships by fire to avoid capture.[31][32] The Royal Navy ended up having to destroy ten of their own vessels in all,[33] including five frigates.[25][Note 4]

The French fleet sailed to Martinique, where Suffren's division joined up with it, and from there to Grenada, leading to the Battle of Grenada on 6 July 1779. Fantasque was at the front of the vanguard, preceding the 74-gun Zélé.[25] When the two fleets came in contact, she came under fire from the 74-gun Royal Oak and the 70-gun Boyne, sustaining 62 men killed or wounded.[34][11] After the battle, Admiral d'Estaing sent Suffren with a 2-ship and 3-frigate division to secure the surrender of Carriacou and Union Island. [35]

On 7 September 1779, d'Estaing ordered Suffren to blockade the mouth of Savannah River, to cover the landing of French troops in support of the Siege of Savannah, and prevent British ships from escaping. Suffren led the 64-gun Artésien and Provence, and the frigates Fortunée, Blanche and Chimère, sailing into the river and forcing the British to scuttle several ships,[36] notably HMS Rose.

On 1 March 1780, Louis XVI granted Suffren a 1,500 French livre pension in recognition of his services.[37] In April, Suffren was given command of the 74-gun Zélé, part of a two-ship squadron along with Marseillais, under Captain d'Albert de Rions.[38] They set sail on 19 May 1780 to patrol off Portugal, and joined up with a division under Rear-Admiral de Beausset in Cadiz on 17 June.[39] He then joined up with a combined Franco-Spanish fleet under Admiral Luis de Córdova y Córdova. On 9 August, the fleet intercepted a large British convoy, leading to the action of 9 August 1780. The British escort, comprising the 74-gun HMS Ramillies, under Captain Sir John Moutray, and the frigates Thetis and Southampton, fled before the vastly superior combined fleet. Suffren attempted to give chase, but the copper sheathing of the British warships gave them a decisive advantage, and he abandoned the pursuit to help with the capture of the merchantmen.[35][11] After the battle, Suffren wrote a letter to Antoine de Sartine, Secretary of State of the Navy, to advocate for the French Navy to copper its own ships.[40][Note 5]

Campaign in the Indian Ocean

With the outbreak of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, France and the Dutch Republic found themselves allied against the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Dutch expected the British to send an expeditionary force to try and capture their Dutch Cape Colony, and Suffren was given command of a 5-ship squadron to reinforce it. The task force comprised the 74-gun Héros (under Suffren) and Annibal (under Trémignon), and the 64-gun Artésien (under Cardaillac), Sphinx (under Du Chilleau) and Vengeur (under Forbin), [41] as well as the 16-gun corvette Fortune (under Lieutenant Lusignan), and seven transports [42] carrying the Régiment de Pondichéry, under Brigadier General Thomas Conway.[43] All these ships had a copper sheathing, except for Fortune and Annibal.[44]

Battle of Porto Praya

The squadron departed Brest on 22 March 1781. En route, Artésien, which had originally been appointed to a shorter mission, found herself short on water, and Captain de Cardaillac requested permission to resupply at Santiago. Suffren gave permission but, unwilling to scatter his forces, ordered his entire squadron to move into Praia Harbour. Arriving there at 0830 the morning of 16 April, Artésien spotted five British warship at anchor; she turned, signalling "enemy ships in sight". Understanding that random chance had put him in contact with George Johnstone's squadron,[45] and disregarding neutrality laws,[25][Note 6] Suffren ordered an immediate attack.[46] At 1000, Suffren's squadron attacked, precipitating the Battle of Porto Praya. Having scattered and disorganised Johnstone's forces, Suffren rushed to The Cape, and arrived at Simon's Bay on 21 June.[47] The Régiment de Pondichéry landed and started fortifying the Cape colony against attacks from land and from the sea, while the fleet repaired its ships and had its sick given medical attention in hospitals ashore.[43]

Johnstone arrived in the morning of 21 July, left two frigates to watch the bay, and sailed on to Saldanha Bay.[43] On 24 July, Suffren set sail with four ships,[Note 7] chased away the British frigates, and patrolled the area around the Cape to ascertain the intentions of the British. Satisfied that Johnstone had renounced attacking the Cape colony, he resupplied and sailed to Isle de France (now Mauritius) with the rest of the squadron, arriving on 28 July.[50]

Preliminary operations at Isle de France

Until the outbreak of the Anglo-French War, the French colony of Pondichéry maintained a small squadron under François-Jean-Baptiste l'Ollivier de Tronjoli[Note 8], comprising the 64-gun Brillant (under Tronjoli), the 40-gun frigate Pourvoyeuse (under Captain Saint-Orens[Note 9], and three armed merchantmen: the 26-gun corvette Sartine (under du Chayla), the 24-gun Brisson (under Captain du Chézeau), and the 24-gun Lawriston.[52] During the Siege of Pondicherry in 1778, Tronjoli had lost some of his ships and escaped to Isle de France with the survivors, arriving there in late September.[53] Pondichéry fell to the British on 17 October.[54] With these reinforcements, the island was guarded by the 64-gun Brillant, the 54-gun Flamand, the frigates Pourvoyeuse and Consolante, and the smaller Subtile (a 24-gun corvette), Elisabeth (a fluyt) and Sylphide (a 12-gun corvette).[53] Furthermore, on 28 December 1778, the 74-gun Orient[Note 10] departed Brest under Thomas d'Estienne d'Orves to reinforce the colony, and on 27 March 1779, so did the 64-gun Sévère, under la Pallière, escorting the transports Hercule and Trois-Amis, arriving on 9 August 1779.[56] With four ships of the line now at his disposal, Tronjoli departed on 6 December 1779 to cruise off the Cape, but to no avail, and he returned to Isle de France on 13 January 1780.[57] On 3 February 1780, the 64-gun Bizarre departed Lorient to further reinforce Isle de France.[58] After it was confirmed that the British had despatched a squadron under Admiral Hughes in the Indian Ocean, France sent a convoy comprising the 64-gun Protée and Ajax, and the frigate Charmante (under Baron de la Haye),[59] escorting 16 transports ferrying the Régiment d'Austrasie under Brigadier Duchemin de Chenneville.[60] En route, the convoy encountered a British squadron under Admiral George Rodney, yielding the action of 24 February 1780 in which Protée sacrificed herself and tree smaller transports to lure the British away from the others. Charmante returned to Lorient to bring the news of the engagement, while the other survivors sailed on to Isle de France. By 1780, Tronjoly was recalled to France, leaving d'Orves in command with a total of six ships of the line at his disposal.[59]

Suffren arrived at Isle de France on 25 October 1781.[61][62] The island had been selected as the base for French operations in the Indian Ocean, falling under the overall command of Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau.[63]

On 7 December 1781, d'Orves led a 27-ship fleet to Ceylon, with his flag on Orient. He had 11 ships of the line, 3 frigates and 3 corvettes at his disposal. En route, d'Orves changed his objectif from Trincomalee to Madras.[64][Note 11] On 19 January, Sévère detected a strange sail, and d'Orves detached Héros and Artésien to investigate. Suffren closed in, making signals according to tables captured at Porto Praya on the East Indiaman Hinchinbrooke, until the ship made signals that he was unable to answer. A chase ensued, and with the night Suffren abandoned the pursuit to rejoin the fleet. On 21, the fleet encountered the same ship again, and again detached Héros, Artésien and Vengeur, but this time with other ships deploying as to ensure communication between the pursuers and the main body of the fleet, allowing Suffren to press on his chase. Suffren caught up with his quarry on 22 around noon and forced her to surrender. She was the 50-gun HMS Hannibal, under Captain Christy, which the French pressed into their service as Petit Annibal.[65]

Battle of Sadras

In the following days, d'Orves' failing health deteriorated to the point where he was not fit for duty, and he delegated command to Suffren.[66] The French intended to surprise the British ships anchored in the roads of Madras. The fleet arrived North of Madras on 5 February 1782, and its light units started preying on coastal merchantmen and capturing cargo of rice.[67] However, the monsoon caused strong winds from the South which trapped the French North of Madras, while at the same time favouring the return of Hughes' squadron from Ceylon to Madras.[68] Upon Hughes' arrival, Lord Macartney warned him of the presence of the French squadron, and Hughes anchored his ships under the protection of Fort St. George and Black Town. On 9 February 1782, Hughes received reinforcements with the arrival of a squadron comprising the 64-gun HMS Monmouth, the 74-gun Hero, the 50-gun Isis and the armed transport Manilla, under James Alms.

D'Orves died the same day at 1600. Suffren re-appointed his captains to the ships of the squadron: Captain de Lapallière[Note 12] took command of Orient and Cillart that of Sévère; Captain Morard de Galles, of Pourvoyeuse, and Lieutenant de Ruyter, in temporary command of Petit Annibal, exchanged their positions; Beaulieu went on Bellone;[70] Tromelin-Lanuguy took on Subtile; and Galifet took Sylphide. General Duchemin transferred from Orient to Héros.[69]

On 14 February, the usual monsoon wind from the North-East resumed, allowing Suffren's squadron to sail South. In the evening, Fine, under Perrier de Salvert, came in view of Madras harbour and Hughes' squadron. Seeing Hugues anchored in a very strong defensive position, Suffren decided to sail off the coast,[71] but to his surprise, Hugues left the safety of the forts and gave chase.[72] Suffren deployed a frigate screen to warn his squadron of Hugues' moves, but during the night Pourvoyeuse drifted away from the fleet due to a navigation error, while Fine lost sight of the British ships, and both thus failed to keep Suffren appraised of Hughes's position.[73] In the morning, signals from Fine informed Suffren that HMS Montmouth, Hero, Isis, Aigle and Burford where approaching the French transports. Suffren rushed with his warships to protect the convoy, and Hughes ordered his ships to regroup and form a line of battle.[74] In the morning of 17 February, the fleets were about 6 km apart[Note 13], the British forming a line and had captured Lawriston, while the French were scattered due to an error in interpreting night signals. Suffren formed a line without consideration for the order of battle,[75] and at 1500 he closed in within gun range, starting the Battle of Sadras.

Suffren sustained about 30 men killed and 100 wounded,[76] and light damage to his riggings.[77] At 1900 he broke contact.[76]

Battle of Providien

Suffren returned to Pondichéry, where he arrived on 19 February 1782 and learned that the British squadron was heading for Trincomalee. After consulting Hyder Ali, he decided not to land his troops in Pondichéry, and rather to head for Porto Nove, where he arrived on 23 February.[78] Hyder Ali despatched André Piveron de Morlat, the French ambassador, to act as an intermediary between Suffren and himself, along with two of his officiers. Suffren negotiated an agreement that French troops would retain their own command; that a 4,000-man cavalry and 6,000-man infantry force would reinforce them; and that they be paid 24 Lakh rupee a year.[79] Suffren landed his troops at Porto Nove, and departed on 23 March to search for the British fleet.

On 10 April, the two fleets came into view, and they spent two days in manoeuvres, trying to gain an advantage on the other.[79] In the morning, Fine captured a British courier and managed to retrieve the dispatches that her captain had thrown overboard, revealing British plans to expel the Dutch from Ceylon.[80] On 12, the Battle of Providien broke out, leaving both squadrons damaged. Suffren retreated to the safety of the Dutch forts of Batacalo to repair, and tend to those members of his crews who were wounded or suffered from scurvy.[79]

Battle of Negapatam

On 3 June 1782, Suffren departed Batacalo and sailed to Cuddalore, where he received letters from Hyder Ali requesting that he lay siege to Nagapattinam. The French troops reembarked on their transports, when Bellone, which had been left to patrol, came with news that Hughes' squadron was at Nagapattinam. Suffren ordered an immediate departure and found the British ships anchored when he arrived on 6 July 1782.[81] Before the battle, Suffren despatched Pourvoyeuse to Malacca, Résolution to Manila, and Fortitude and Yarmouth to Isle de France, to purchase spare spars, food and ammunition to resupply his fleet. He furthermore kept Sylphide and Diligent handy to bring news of the outcome of the battle to Isle de France.[82]

The Battle of Negapatam ensued. The two fleets exchanged fire to over 4 hours, until Hughes retreated.[81] During the battle, Captain Cillart,[83][Note 14] captain of Sévère, panicked and struck his colours but two of the officers, named Dieu and Kerlero de Rosbo,[84] refused to surrender and resumed firing. HMS Sultan had stopped to launch her boats and take possession of Sévère, and sustained serious damage when the broadsides of Sévère suddenly raked her.[85] Seeing his hand forced, Cillart ordered his flag hoisted again. [86][Note 15]

Suffren cruised off Nagapattinam to observe the moves of the British ships, and seeing them idle, returned to Cuddalore to repair.[88] On the way, HMS Rodney joined up as cartel with Héros, with Captain James Watt of HMS Sultan[89] bringing a letter from Hughes demanding that Suffren hand over Sévère after her surrender. Suffren answered that he was unaware that Sévère had surrendered and promised to launch an investigation, and also warned that without orders from his government he was not at liberty to give away his ships.[88]

Following the incident with Sévère, Suffren relieved Cillart of duty and sent him back to Isle de France to be returned to France and court-martialed.[90] He also dismissed Maurville of Artésien, Forbin of Vengeur and De Ruyter of Pourvoyeuse, as well as three more junior officers.[86] Command of Artésien went to Saint-Félix; that of Vengeur went to Cuverville, himself replaced by Lieutenant Perier de Salvert at the command of Flamand; Lieutenant Maureville de Langle was promoted to the command of Sévère; Lieutenant de Beaumont le Maître received command of Ajax, replacing Bouvet de Précourt; and Brillant went to Beaulieu, himself replaced on Bellone by Pierrevert.[91] Later, Beaulieu returned to Bellone after Pierrevert's death in the action of 12 August 1782,[92] and from then on Lieutenant de Kersauson captained Brillant.[93]

Battle of Trincomalee

On 25 July 1782, Hyder Ali arrived at Bahour under the gun salutes of the fortress and the whole French squadron. The next day, a 500-man cavalry troop under General Ghulam Ali Khan escorted Suffren, six of his captains and several officers to the encampment of Hyder Ali's army for a meeting with him.[86] Suffren announced that Bussy-Castelnau had arrived to Isle de France with 6 ships of the line, 2 frigates and transports carrying 5,000 soldiers. He also informed Hyder Ali that a French frigate had intercepted a British schooner carrying Colonal Horn to Nagapattinam. Hyder Ali responded with luxurious gifts to Suffren and his officers, or with gifts represented by their equivalent value in rupees. He then ajourned the meeting until the next day. [94][Note 16]

On 27, Hyder Ali invited Suffren and Piveron to a private dinner, with European-style seating in deference to his guests.[95][Note 17] Suffren reported on the battles against Hughes, and they reviewed plans of operations against the British. Hyder Ali was especially concerned by British advance on the Malabar Coast and the risk that the Maratha Empire would switch sides, ally with the British and start a war with Mysore.[Note 18] The next day, Fine joined the squadron with a prize carrying British colonel Horn, of the Madras Army, and Lézard brought news of the arrival of Bussy-Castelnau, with the 74-gun Illustre and the 64-gun Saint Michel, on the theatre of operations.[96]

Meanwhile, the French squadron was effecting repairs, especially to its rigging, and Pourvoyeuse sailed to Malacca to pick up spars.[97][98] In early August, Suffren learnt that the British fleet had departed Nagapattinam and was embarking troops in Madras, bound for an unknown destination. Suffren departed at once for Tharangambadi in the hope of discovering the British plans. Failing to do so, he sailed to Batticaloa, where he arrived on 8 August to find Consolante, arrived from Isle de France three days earlier. From Consolante, Suffren learnt that Bussy's Illustre and Saint Michel were awaiting him at Galle with 8 transports of troops and supplies. Suffren had sent a light ship to Trincomalee, which returned announcing that the British ships were not there. Suffren then decided to lay siege to Trincomalee.[97]

On 21 August, the two ships of the convoy arrived. Suffren had ammunition from the convoy distributed among his warships to replenish their magazines, and explained his intentions to the captains. [97] The same day, the cutter Lézard arrived, bringing despatches. The letter, dated from 22 November 1781, notably carried official approval of Suffren's conduct at the Battle of Porto Praya, granted the requests he had made to appoint his officers, and promoted him to Chef d'Escadre.[99] Furthermore, a letter from Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, informed him that he was promoted to Bailiff (Bailli) of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[100][101]

On 25 August, the fleet set sail and formed a battle line, soon arriving in view of the forts of Trincomalee. 2,000 men quickly landed, with siege artillery, ammunition and three days worth of rations. By 29, the French had completed their siege battery emplacements, and they started bombarding the fort. On 30, at 0900, Suffren sent a message to the fort of Trincomalee to negotiate its capitulation. Captain Hay MacDowall surrendered the fort in exchange for its 1,000-man garrison to be sent to Madras.[100] [102] The next day, Captain Quelso, low on water, surrendered Fort Ostenburg under the same conditions.[103]

On 3 September, the British fleet arrived. Suffren reembarked his troops and moved to intercept, leading to the Battle of Trincomalee.[104] The French line fought disorganised, especially after Vengeur caught fire and had to distance herself from the other ships. The flag of Héros was shot away by British fire and Suffren had new French ensigns hoisted to continue the fight. After an hour and a half, night fell and the battle ended. Suffren was furious at the conduct of his captains, whom he accused of abandoning him.[105] The next day, the British fleet had disappeared, and Suffren returned to Trincomalee, where he arrived in the evening of 7 September 1782.[106]

Battle of Cuddalore

When the French squadron arrived at Trincomalee in the evening of 7 September 1782 after the Battle of Trincomalee, its ships were seriously damaged. Héros, in particular, was leaking and had lost her foremast and mainmast. The ships anchored to effect repairs, which the crew completed in two weeks. [106] Around that time, Captains Tromelin, Saint-Félix and la Landelle-Roscanvec, who could not get along with Suffren, requested to be relieved. So did Morard de Galles, who was wounded and weakened. On 23 September 1782, Suffren sent Pulvérisateur to Isle de France under M. Le Fer to bring despatches to Governor François de Souillac, with the four captains aboard.[107] This yielded another reshuffle: Annibal went to Captain d'Aymar, Artésien to Captain de Vigues, Saint-Michel to Dupas, Petit-Annibal to Beaulieu, Bizarre to Lieutenant Tréhouret de Pennelé, Fine to Saint-Georges, Bellone to Villaret-Joyeuse, Consolante to Malis, and Lézard to Dufreneau.[108]

Meanwhile, Suffren received news that Hyder Ali had left Cuddalore with his army to fight in the North, leaving the city vulnerable to a British attack from Madras. As Cuddalore was a crucial supply depot, it was imperative for Suffren to protect it. Suffren departed Trincomalee on 1 October to reinforce Cuddalore,[106] arriving on 4 October. The expected British attack did not happen, and on 12 October, the change in monsoon forced both fleets to shelter in harbour. Hughes anchored at Bombay, [109] while Suffren chose to sail to Aceh. By choosing Aceh, Suffren avoided both being driven away from the battlefield as he would have by choosing Isle de France, and the climate of Trincomalee which he feared would be detrimental to his crew.[109]

The French squadron left Cuddalore on 15 October 1782 and arrived at Aceh on 1 November. Pourvoyeuse and Bellone arrived shortly after with spare parts, and the fleet spent the following weeks tending to the sick and effecting repairs.[110] After a while, a corvette arrived from Isle de France, bringing news that a 3-ship squadron under Antoine de Thomassin de Peynier was about to arrive, escorting a convoy ferrying troops and ammunitions, as well as Bussy-Castelnau.[111]

Suffren's fleet set sail on 20 December to return to Coromandel. On the way, it raided the British colony of Ganjam, destroying a number of merchantmen. On 12 January 1783, the frigate HMS Coventry, unaware of the presence of the French fleet and mistaking its ships for East Indiamen, approached and had to surrender. From the prisoners, Suffren learnt of Hyder Ali's death. The fleet continued to Cuddalore, arriving there on 1 February.[111] Peynier's squadron of 3 ships and 1 frigate arrived shortly afterwards with 30 transports, survivors of a much larger convoy that had lost a number of ships to the elements and to the British. [112]

With the return of favourable weather, Suffren expected and feared Hughes' attack, as his own ships were either damaged after long cruises, or had at best only received field repair at Aceh. He therefore quickly landed his troops at Cuddalore and set sail for Trincomalee. Unfavourable winds made progression difficult and as Suffren's squadron entered the bay, Fine reported 17 sails closing in.[112] The French squadron retreated into the safety of Trincomalee and started repairing. [113]

On 24 May, Hughes' squadron passed off Trincomalee. A few days later, a ship brought letters from Bussy-Castelnau announcing that Cuddalore was besieged and blockaded.[113] Suffren departed Trincomalee on 11 June 1783 and passed off Tharangambadi on 16, when the frigate screen signaled 18 ships in view. Suffren transferred onto the frigate Cléopâtre to personally reconnoitre the situation. The two fleets approached each other in the evening manoeuvered without engaging. In the morning, the French found themselves at the entrance of Cuddalore Bay, while the British squadron was further off at sea.[114] Suffren anchored his ships and spent the night reinforcing his crew with 1,200 soldiers from ashore.[115] On 18 June, Suffren set sail and the two squadrons chased each other for two days, trying to gain an advantage. Finally, on 20, the two fleets came in contact and engaged, starting the Battle of Cuddalore at 1530. [115]

On 25, Hughes retreated to Madras,[116] and on 29, a British frigate came as a cartel,[117] bringing news of the preliminary agreements to the Treaty of Paris that had been signed on 9 February 1783, and Hughes' offer of a cease-fire. Suffren accepted. On 25 July, the frigate Surveillante arrived from Europe with news of the Peace of Paris and orders to Suffren to return to France, leaving 5 ships under Peynier in the Indian Ocean.[118]

Post-War

Suffren's squadron arrived at Trincomalee on 8 August. Most of it remained there until October. Suffren himself sailed to Pondichéry on 15 September with Héros and Cléopâtre to confer with Bussy, arriving on 17. There, he learnt of his promotion to Lieutenant général des Armées navales.[119] He departed for Trincomalee on 26, arriving on 29. The fleet departed for Europe on 6 October. [120] On his way, Suffren called the Cape of Good Hope, and had stayed there for a few days when Hughes' squadron arrived, with unfavourable winds. HMS Exeter ran aground,[121] and both the British and French ships launched their boats to provide assistance.[122]

Suffren arrived at Toulon on 26 March 1784. Summoned to Versailles, he was received by Navy Minister Castrie and by Louis XVI, and much celebrated. [122] A fourth position of vice-admiral was created especially for Suffren, the decree stipulating that it would be suppressed after his death.[123]

In October 1787, with the implementation of the Eden Agreement, tensions again flared up between France and England, and it was feared that a new conflict was looming. As a precaution, Louis XVI ordered the Brest squadron be readied, and he appointed Suffren to command it, leaving him the choice of his captains. As he prepared for the journey to Brest, Suffren's health suddenly declined. He died in Paris on 8 December 1788.[124]

Legacy

Assessment

Suffren was generally recognised as an able commander. The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition called him "perhaps the ablest sea-commander that France ever produced'.[125] In The Influence of Sea Power upon History, Mahan writes:

The military situation... demanded first the disabling of the hostile fleet, next the capture of certain strategic ports. That this diagnosis was correct is as certain as that it reversed the common French maxims, which would have put the port first and the fleet second as objectives.[126]

Lacour-Gayet cites Suffren's instructions before the Battle of Sadras as reminiscent of Nelson's style, in that he was giving advance instruction for a variety of scenarios and was attempting to take the British in a cross-fire and destroy their squadron. [127] In 1942, Admiral Ernest King listed his five favourite admirals of the past as Jervis, Nelson, Tromp, Suffren and Farragut.[128]

On the other hand, Las Cases, who had served as a lieutenant in the navy, described Suffren to Napoléon as "A hard man, very weird, egoistic in the extreme, bad-tempered, poor comrade in arms, liked of no one."[129][Note 19] More recently, François Caron stated "while Chevalier de Suffren displayed an indisputable bravery and an incomparable tactical insight, an analysis of his action shows it to be banal and disappointing."[130]

Rémi Monaque offers a more nuanced assessment, finding Suffren an aggressive and innovative commander comparable to Ruyter and Nelson,[131] but also one whose lack of didactic qualities and social graces made him misunderstood and disliked by his captains, and thus failed to develop his full potential.[132]

Monuments and memorials

Eight ships of the French Navy have been named Suffren in honour of Suffren de Saint Tropez.

A number of streets and avenues through France are named in Suffren's honour. In Paris, the Avenue de Suffren runs alongside the Champ de Mars.

Suffren, by Pompeo Batoni.

Suffren, by Pompeo Batoni.-white.jpg.webp) Suffren's statue in Saint Tropez.

Suffren's statue in Saint Tropez. The envoys Mattheus Lestevenon and Gerard Brantsen presenting vice-admiral Pierre André Bailly de Suffren de Saint Tropez with a golden sword in 1784

The envoys Mattheus Lestevenon and Gerard Brantsen presenting vice-admiral Pierre André Bailly de Suffren de Saint Tropez with a golden sword in 1784 Bust of Suffren by Brion, on display at Paris naval museum.

Bust of Suffren by Brion, on display at Paris naval museum.

Notes

- ↑ usually pronounced [syfʁɛn], historically [syfʁɛ̃] and still pronounced in this way in the French Navy[3]

- ↑ The older son was an Army officer; the second, a priest; the third and fourth sons were Navy officers; the oldest daughter married Marquis de Pierrevert, and the youngest married Marquis de Nibles de Vitrolles.[7]

- ↑ Alternatively spelt "Macnémara", "Macnemara"[10] or "Macnamara"

- ↑ The remains of the Cerberus are now part of a site listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the "Wreck Sites of HMS Cerberus and HMS Lark."

- ↑ The full text of Suffren's memorandum on copper sheathing is quoted in Cunat, p.353-354

- ↑ Several authors attribute Suffren's disregard for neutrality law to his experience at the Battle of Lagos, 20 years earlier.[25][46][45]

- ↑ Annibal was in need of more extensive repairs to her rigging:[48] after losing her masts at Porto Praya, she had done the rest of the journey in two of Sphinx.[49]

- ↑ Sometimes spelt "Tronjoly"[51]

- ↑ Cunat spells "Saint-Orins"[52]

- ↑ Built as an 80-gun, Orient had been reduced to a 74-gun in early 1766[55]

- ↑ Present-day Chennai

- ↑ Sometimes spelt "la Pallière"[69]

- ↑ one League and a half[74]

- ↑ Also known as Villeneuve-Cilart [83]

- ↑ When known in France, the anecdote yielded the pun that "Villeneuve-Cilart wanted to surrender, but "God" (Dieu, the name of the insubordinate officer) would not allow it".[86] Dieu would be killed on Sévère at the Battle of Cuddalore on 20 June 1783.[87]

- ↑ Suffren received 10,000 rupees symbolising the gift of an elephant, which would have been inconvenient on Héros; his officers received 1,000 symbolising horses, for the same reason.[94]

- ↑ The previous day, Suffren, who was overweight, had suffered from the Indian-style seating and Hyder Ali had graciously bent the etiquette to accommodate him.[95]

- ↑ The Maratha–Mysore War was to start three years later.

- ↑ Un jour, à Sainte-Hélène, Las Cases, qui avait été lieutenant de vaisseau à l'époque de la Révolution, traçait à Napoléon le portrait de l'adversaire de Hughes : « M. de Suffren, très dur, très bizarre, extrêmement égoïste, mauvais coucheur, mauvais camarade, n'était aimé de personne. ».[129]

Citations

- ↑ Cunat, p.382

- ↑ Les voyages du Bailli de Suffren Archived 2008-12-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Monaque, Suffren (2009), p.2, also cited at

- 1 2 3 Hennequin (1835), p. 289.

- 1 2 3 Cunat (1852), p. 3.

- ↑ Geneanet: Paul de Suffren

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 2-3.

- ↑ Monaque (2017), p. 85.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 9.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 11.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 12.

- ↑ Monaque (2017), p. 86.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 15.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 18.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 19.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 290.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 25.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 26.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 27.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 29.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 30.

- ↑ Willis 2009, p. 761.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Monaque (2017), p. 87.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Cunat (1852), p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hennequin (1835), p. 291.

- 1 2 3 Cunat (1852), p. 33.

- ↑ Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 456.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 37.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 292.

- ↑ Hepper (1994), p. 52.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 38.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 39.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 40.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 41.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 42.

- ↑ Diaz de Soria (1954), p. 11.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 44.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 48.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 49.

- 1 2 3 Cunat (1852), p. 63.

- ↑ Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 480.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 294.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 50.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 62.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 65.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 295.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 64.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 74.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 69.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 72.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 71.

- ↑ Demerliac (1996), p. 17, n°22.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 73.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 75.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 81.

- 1 2 Cunat (1852), p. 83.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 82.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 94.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 297.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 95.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 97.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 99.

- ↑ Cunat, p.100

- ↑ Cunat, p.101

- ↑ Cunat, p.102

- 1 2 Cunat, p.104

- ↑ Cunat, p.103

- ↑ Cunat, p.105

- ↑ Cunat, p.106

- ↑ Cunat, p.108

- 1 2 Cunat, p.109

- ↑ Cunat, p.111

- 1 2 Cunat, p.115

- ↑ Cunat, p.116

- ↑ Hennequin, p.299

- 1 2 3 Hennequin, p.302

- ↑ Cunat, p. 127

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 303.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 164.

- 1 2 "de Cillart (Chevalier de Cillart)". Three Deck's Forum.

- ↑ Roche (2005), p. 414.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 305.

- 1 2 3 4 Hennequin (1835), p. 306.

- ↑ Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 546.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 304.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 177.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 179.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 180.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 201.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 217.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 308.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 309.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 192.

- 1 2 3 Hennequin (1835), p. 311.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 193.

- ↑ Caron (1996), p. 347.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 312.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 202.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 210.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 211.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 314.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 316.

- 1 2 3 Hennequin (1835), p. 317.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 231.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 232.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 318.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 319.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 320.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 321.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 322.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 323.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 324.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 326.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 327.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 328.

- ↑ Monaque (2009), p. 320.

- ↑ Monaque (2009), p. 321.

- ↑ Cunat (1852), p. 338.

- 1 2 Hennequin (1835), p. 329.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 330.

- ↑ Hennequin (1835), p. 331.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 660.

- ↑ Mahan, A.T., The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660–1783, p. 433 ISBN 0-486-25509-3

- ↑ Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 502.

- ↑ Monaque (2009), p. 14.

- 1 2 Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 525.

- ↑ Monaque (2009), p. 15.

- ↑ Monaque (2017), p. 91.

- ↑ Monaque (2017), p. 90.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Suffren Saint Tropez, Pierre André de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Caron, François (1996). La guerre incomprise, ou, Le mythe de Suffren: la campagne en Inde, 1781-1783. Service historique de la marine. OCLC 463973942.

- Cunat, Charles (1852). Histoire du Bailli de Suffren. Rennes: A. Marteville et Lefas. p. 447.

- Demerliac, Alain (1996). La Marine de Louis XVI: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1774 à 1792 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-906381-23-3.

- Glanchant, Roger (1976). Suffren et le temps de Vergennes (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hennequin, Joseph François Gabriel (1835). Biographie maritime ou notices historiques sur la vie et les campagnes des marins célèbres français et étrangers (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Regnault éditeur. pp. 289–332.

- Hepper, David J. (1994). British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail, 1650–1859. Rotherfield: Jean Boudriot. ISBN 0-948864-30-3.

- Lacour-Gayet, Georges (1905). La marine militaire de la France sous le règne de Louis XVI. Paris: Honoré Champion. OCLC 763372623.

- Monaque, Rémi (2017). "Le Bailli Pierre-André de Suffren: A Precursor of Nelson". Naval Leadership in the Atlantic World: The Age of Reform and Revolution, 1700–1850. University of Westminster Press. pp. 85–92. ISBN 9781911534082. JSTOR j.ctv5vddxt.12., CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

- Monaque, Rémi (2009). Suffren. Tallandier. ISBN 9791021002364.

- Mores, ed. (1888). Journal de Bord du Bailli de Suffren dans l'Inde.

- Thayer Mahan, Alfred (1890). Harding, Richard; Guimerá, Agustín (eds.). The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660–1783. London: Little, Brown and Co.

- Klein, Charles-Armand (2000). Mais qui est le bailli de Suffren Saint-Tropez ?. Mémoires du Sud – Editions Equinoxe. ISBN 2841352056. OCLC 51607247.

- Diaz de Soria, Ollivier-Zabulon (1954). Le Marseillois, devenu plus tard le Vengeur du peuple (in French). F. Robert et fils.

- Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours. Vol. 1. Group Retozel-Maury Millau. ISBN 978-2-9525917-0-6. OCLC 165892922.

- Taillemite, Étienne (2010) [1988]. Histoire ignorée de la Marine française (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03242-5.

- Willis, Sam (2009). "The Battle of Lagos, 1759". The Journal of Military History. 73 (3): 745–765. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0366. ISSN 0899-3718. S2CID 162390731.

Iconography

- Engraving by Mme de Cernel after an original by Gerard.

External links

Media related to Pierre André de Suffren at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pierre André de Suffren at Wikimedia Commons- (in French) Composition de l'escadre sous Suffren aux Indes (1781–1783)