Московский Физико-Технический институт | |

| |

| Motto | Sapere aude |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Dare to know |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | 1946 |

Parent institution | Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Russia) |

| Affiliation | Russian Academy of Sciences |

| President | Nikolay Kudryavtsev |

| Rector | Dmitry Livanov |

Academic staff | 1,110 |

| Students | 6,040 |

| Undergraduates | 4,288 |

| Postgraduates | 1,751 |

| Location | , Russia 55°55′46″N 37°31′17″E / 55.92944°N 37.52139°E |

| Campus | Urban |

| Language | Russian |

| Colours | Blue & white |

| Website | mipt.ru/english |

| |

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| USNWR Global | 475 |

| Regional – Overall | |

| QS Emerging Europe and Central Asia[1] | 10 (2022) |

Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT; Russian: Московский Физико-Технический институт, also known as PhysTech), is a public research university located in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It prepares specialists in theoretical and applied physics, applied mathematics and related disciplines.

The main MIPT campus is located in Dolgoprudny,[2] a northern suburb of Moscow. However the Aeromechanics Department is based in Zhukovsky, a suburb south-east of Moscow.

In international rankings, the university was ranked 44th by The Three University Missions Ranking in 2022, In 2020 and 2021, Times Higher Education ranked MIPT #201 in the world, in 2022 QS World University Ratings ranked it #290 in the world, in 2022 U.S. News & World Report ranked it #475 in the world, and in 2022 Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked it #501 in the world.[3][4][5][6] As Phystech's founder, Pyotr Kapitsa, designed the institute inspired by and in accordance with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology model, Phystech is commonly hailed as the "MIT of Russia" and is considered to be the leading specialized technical institution of higher education in the former Soviet Union.[7]

Nikolay Kudryavtsev (Кудрявцев Николай Николаевич]), the rector of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology has signed a letter of support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[8]

History

In late 1945 and early 1946, a group of Soviet scientists, including the future Nobel Prize winner Pyotr Kapitsa, lobbied the government for the creation of a higher educational institution radically different from the type established in the Soviet system of higher education. Applicants, selected by challenging examinations and personal interviews, would be taught by and work together with, prominent scientists. Each student would follow a personalized curriculum created to match his or her particular areas of interest and specialization. This system would later become known as the Phystech System.

In a letter to Stalin in February 1946, Kapitsa argued for the need for such a school, which he tentatively called the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, to better maintain and develop the country's defense potential. The institute would follow the principles outlined above and was supposed to be governed by a board of directors of the leading research institutes of the USSR Academy of Sciences. On March 10, 1946, the government issued a decree mandating the establishment of a "College of Physics and Technology" (Russian: Высшая физико-техническая школа).[9]

For unknown reasons, the initial plan came to a halt in the summer of 1946. The exact circumstances are not documented, but the common assumption is that Kapitsa's refusal to participate in the Soviet atomic bomb project and his disfavor with the government and communist party that followed, cast a shadow over an independent school based largely on his ideas. Instead, a new government decree was issued on November 25, 1946, establishing the new school as a Department of Physics and Technology within Moscow State University. November 25 is celebrated as the date of MIPT's founding.[10]

Kapitsa foresaw that within a traditional educational institution, the new school would encounter bureaucratic obstacles, but even though Kapitsa's original plan to create the new school as an independent organization did not come to fruition exactly as envisioned, its most important principles survived intact. The new department enjoyed considerable autonomy within Moscow State University. Its facilities were in Dolgoprudny (the two buildings it occupied are still part of the present day campus), away from the MSU campus. It had its own independent admissions and education system, different from the one centrally mandated for all other universities. It was headed by the MSU "vice rector for special issues"—a position created specifically to shield the department from the university management.

As Kapitsa expected, the special status of the new school with its different "rules of engagement" caused much consternation and resistance within the university. The immediate cult status that Phystech gained among talented young people, drawn by the challenge and romanticism of working on the forefront of science and technology and on projects of "government importance," many of them classified, made it an untouchable rival of every other school in the country, including MSU's own Department of Physics. At the same time, the increasing disfavor of Kapitsa with the government (in 1950 he was essentially under house arrest) and anti-semitic repressions of the late 1940s made Phystech an easy target of intrigues and accusations of "elitism" and "rootless cosmopolitanism." In the summer of 1951, the Phystech department at MSU was shut down.[11]

A group of academicians, backed by Air Force general Ivan Fedorovich Petrov, who was a Phystech supporter influential enough to secure Stalin's personal approval on the issue, succeeded in re-establishing Phystech as an independent institute. On September 17, 1951, a government decree re-established Phystech as the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology.[12]

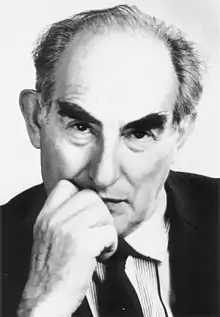

Apart from Kapitsa, other prominent scientists who taught at MIPT in the years that followed included Nobel prize winners Nikolay Semyonov, Lev Landau, Alexandr Prokhorov, Vitaly Ginzburg; and Academy of Sciences members Sergey Khristianovich, Mikhail Lavrentiev, Mstislav Keldysh, Sergey Korolyov and Boris Rauschenbach. MIPT alumni include Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, the 2010 winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics.[13]

The Phystech System

The key principles of the Phystech System, as outlined by Kapitsa in his 1946 letter arguing for the founding of MIPT:

- Rigorous selection of gifted and creative young individuals.

- Involving leading scientists in student education, in close contact with them in their creative environment.

- An individualized approach to encourage the cultivation of students' creative drive and to avoid overloading them with unnecessary subjects and rote learning common in other schools and necessitated by mass education.

- Conducting their education in an atmosphere of research and creative engineering, using the best existing laboratories in the country.

Departments

The institute has eleven departments, ten of them averaging 80 students admitted annually.[14]

- Radio Engineering and Cybernetics

- General and Applied Physics

- Aerophysics and Space Research

- Molecular and Biological Physics

- Physical and Quantum Electronics

- Aeromechanics and Flight Engineering

- Applied Mathematics and Control

- Problems of Physics and Power Engineering

- Innovation and High Technology

- Nano-, Bio-, Information and Cognitive Technologies

Admissions

Most students apply to MIPT immediately after graduating from high school at the age of 18. Traditionally, applicants were required to take written and oral exams in both mathematics and physics, write an essay and have an interview with the faculty. In recent years, oral exams have been eliminated, but the interview remains an important part of the selection process. The strongest performers in national physics and mathematics competitions and IMO/IPhO participants are granted admission without exams, subject only to the interview.

In accordance with the traditions of the Soviet education system, education at MIPT is free for most students. Further, students receive small scholarships (as of 2020, $70–105 for bachelor's and $110–140 for master's degree per month,[15] depending on the student's performance) and rather cheap (as of 2020, $13–20[16] per month, depending on location and comfort) housing on campus.

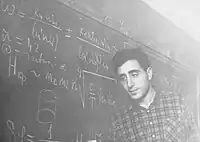

Education

It normally takes six years for a student to graduate from MIPT. The curriculum of the first three years consists exclusively of compulsory courses, with emphasis on mathematics, physics and English. There are no significant curriculum differences between the departments in the first three years. A typical course load during the first and second years can be over 48 hours a week, not including homework. Classes are taught five days a week, beginning at 9:00 am or 10:30 am and continuing until 5:00 pm, 6:30 pm, or 8:00 pm. Most subjects include a combination of lectures and seminars (problem-solving study sessions in smaller groups) or laboratory experiments. Lecture attendance is optional, while seminar and lab attendance affects grades. Andre Geim, a graduate and Nobel prize winner stated "The pressure to work and to study was so intense that it was not a rare thing for people to break and leave and some of them ended up with everything from schizophrenia to depression to suicide."[17]

MIPT follows a semester system. Each semester includes 15 weeks of instruction, two weeks of finals and then three weeks of oral and written exams on the most important subjects covered in the preceding semester. Starting with the third year, the curriculum matches each student's area of specialization and also includes more elective courses. Most importantly, starting with the third year, students begin work at base institutes (or "base organizations," usually simply called bases). The bases are the core of the Phystech system. Most of them are research institutes, usually belonging to the Russian Academy of Sciences. At the time of enrollment, each student is assigned to a base that matches his or her interests. Starting with the third year, a student begins to commute to their base regularly, becoming essentially a part-time employee. During the last two years, a student spends 4–5 days a week at their base institute and only one day at MIPT.[18]

The base organization idea is somewhat similar to an internship in that students participate in "real work." However, the similarity ends there. All base organizations also have a curriculum for visiting students and besides their work, the students are required to take those classes and pass exams. In other words, a base organization is an extension of MIPT, specializing in each particular student's area of interests. While working at the base organization, a student prepares a thesis based on his or her research work and presents ("defends") it before the Qualification Committee consisting of both MIPT faculty and the base organization staff. Defending the thesis is a requirement for graduation.

Base organizations

As of 2005, MIPT had 103 base organizations. The following list of institutes is currently far from being complete:

- Center for Arms Control, Energy and Environmental Studies (established 1991) [19]

- Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology RAS

- Gromov Flight Research Institute

- Institute for Information Transmission Problems RAS

- Institute for Nuclear Research RAS

- Institute for Physical Problems

- Institute for High Energy Physics (1963)

- Institute for Problems in Mechanics RAS

- Institute for Spectroscopy Russian Academy of Sciences

- Institute for Theoretical and Experimental Physics

- Institute of Biochemical Physics RAS

- Institute of Molecular Genetics RAS

- Institute of Numerical Mathematics RAS

- Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics RAS (1956)

- Institute of Radio Engineering and Electronics of RAS

- Institute of Solid State Physics RAS

- Institute of Synthetic Polymer Materials RAS

- Joint Institute for Nuclear Research

- Kurchatov Institute (formerly Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy)

- Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics

- Lebedev Institute of Physics RAS (FIAN)

- Lebedev Institute of Precision Mechanics and Computer Engineering

- N.N. Andreyev Acoustics Institute

- N.N. Semenov Institute of Chemical Physics, RAS

- Nuclear Safety Institute of RAS (IBRAE)

- Shirshov Institute of Oceanology

- Shubnikov Institute of Crystallography RAS

- Space Research Institute RAS (1965)

- Steklov Institute of Mathematics

- Zhukovsky Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute

- and a number of OKBs (experimental design bureaux)

In addition, a number of Russian and Western companies act as base organizations of MIPT. These include:

- 1C Company

- ABBYY

- Competentum Group or Physicon

- NPMP "Concept Consulting"

- Intel

- IPG Photonics

- Kraftway

- MetaSynthesis

- Paragon Software Group

- S.P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia

- SWsoft

- Yandex

Degrees

Before 1998, students could graduate only after completing the full six-year curriculum and defending their thesis. Upon graduation, they were awarded a specialist degree in Applied Mathematics and Physics and, beginning in the early 1990s, a Master's degree in Physics. Since 1998, students have been awarded a Bachelor's degree diploma after four years of study and the defense of a Bachelor's "qualification work" (effectively a smaller and less involved version of the Master's thesis).

The full course of education at MIPT takes six years to complete, just like an American bachelor's degree followed by a master's degree. The MIPT curriculum is more extensive compared to an average American college according to the school.[20] There is an opinion at the school that an MIPT specialist/Master's diploma may be roughly equivalent to an American PhD in physics.[21]

Rankings

In 2020 and 2021, Times Higher Education ranked MIPT #201 in the world, in 2022 QS World University Ratings ranked it #290 in the world, in 2026 U.S. News & World Report ranked it #475 in the world, and in 2022 Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked it #501 in the world.[4][5][6][3]

Traditional university rankings are often based in part on the universities' research output and prizes won by faculty.[22]

People

Demographics

About 15% of all students are residents of Moscow and nearly the same are from Moscow region; the rest come from all over the former Soviet Union. The student population is almost exclusively male, with the female/male ratio in a department rarely exceeding 15% (seeing 2–3 women in a class of 80 is not uncommon). In 2009 more than 20% of first year students were females.[23]

There are no reliable statistics on the careers of MIPT graduates.

Notable faculty and alumni

Scientists

Nobel Prize winners

- Lev Landau – physicist, Nobel Prize 1962[24]

- Pyotr Kapitsa – discovered superfluidity,[25] Nobel Prize 1978[26]

- Nikolay Semyonov – best known for his work on chain reactions, Nobel Prize 1956[27] in chemistry

- Vitaly Ginzburg – physicist, Nobel Prize 2003,[28] co-developer of the Soviet H-bomb

- Alexandr Prokhorov – an Australian-Soviet-Russian co-inventor of the laser, Nobel Prize 1964[29]

- Alexey Abrikosov – Soviet-Russian-American theoretical physicist whose main contributions were in the field of condensed matter physics.

- Igor Tamm – physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, for their discovery of Cherenkov radiation.

- Andrei Sakharov – nuclear physicist, dissident, Nobel laureate, and activist for disarmament, peace, and human rights.

- Sir Andrey Geim – Russian-Dutch-British discoverer of graphene, gecko tape and levitating frogs; Fellow of the Royal Society, Nobel Prize in physics, 2010

- Sir Konstantin Novoselov – Russian-British, Nobel Prize in physics for graphene research, 2010

Other notable scientists

- Alexander Andreev – a theoretical physicist best known for explaining the eponymous Andreev reflection

- Alexander Belavin - a physicist, known for his contributions to string theory

- Boris Babayan – a pioneer of Russian supercomputers, an Intel Fellow 2004[30] and software architect

- Oleg Belotserkovsky – rector of MIPT (1962–1987), mathematician and mechanician

- Spartak Belyaev - a theoretical physicist contributed to nuclear physics

- Andrei Bolibrukh – a mathematician who solved Hilbert's twenty-first problem in 1989[31]

- Gersh Budker - Soviet physicist, specialized in nuclear physics and accelerator physics

- Boris Chertok - electrical engineer and the control systems designer in the Soviet Union's space program

- Nikolai Borisovich Delone – physicist who discovered multiphoton ionization

- Gerasim Eliashberg - physicist who contributed to the theory of superconductivity and statistical physics

- Igor Dzyaloshinskii - theoretical physicist, known for his research on magnetism, multiferroics, one-dimensional conductors, liquid crystals, van der Waals forces, and applications of methods of quantum field theory

- David A. Frank-Kamenetskii - theoretical physicist and chemist

- Alexey Fridman - physicist

- Vsevolod Gantmakher - experimental physicist

- Semyon Gershtein – a theoretical physicist who contributed to nuclear physics, particle physics and astrophysics

- Victor Glushkov - a Soviet mathematician, the founding father of information technology in the Soviet Union and one of the founding fathers of Soviet cybernetics

- Lev Gor'kov – a Russian-American theoretical physicist known for his pioneering work in the field of superconductivity

- Yurij Ionov – discovered genome instability as a mechanism in colonic carcinogenesis[32]

- Alexander Holevo – a mathematician known for Holevo's theorem

- Isaak Khalatnikov -- a Soviet theoretical physicist who has made contributions to many areas of theoretical physics, including general relativity, quantum field theory, as well as the theory of quantum liquids

- Alexey Kitaev - a Russian-American theoretical physicist, best known for introducing the quantum phase estimation algorithm and the concept of the topological quantum computer

- Sergey Korolev - a Soviet rocket engineer and spacecraft designer during the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s

- Leonid Keldysh – a theoretical physicist known for developing the Keldysh formalism

- Mstislav Keldysh - a Soviet mathematician who worked as an engineer in the Soviet space program. Among scientific circles of USSR Keldysh was known with epithet "the Chief Theoretician" in analogy with epithet "the Chief Designer" used for Sergey Korolyov.

- Leonid Khachiyan – Soviet-American mathematician and computer scientist famous for his Ellipsoid method for linear programming, Fulkerson Prize (1982)

- Vadim Knizhnik - physicist known for the Knizhnik–Zamolodchikov equations

- Igor Kurchatov - a Soviet nuclear physicist who is known as the director of the Soviet atomic bomb project

- Anatoly Larkin - theoretical physicist, recognised as a leader in theory of condensed matter, and who was also a teacher of several generations of theorists

- Grigory Landsberg -Soviet physicist who worked in the fields of optics and spectroscopy. Together with Leonid Mandelstam he co-discoverer inelastic combinatorial scattering of light, which known as Raman scattering

- Sergei Lebedev – invented MESM (1950) and BESM (1953) mainframe computers

- Evgeny Lifshitz - physicist

- Robert Liptser - Russian-Israeli mathematician who made contributions to the theory and applications of stochastic processes

- Alexander Migdal – Russian-American, defined 2D quantum gravity,[33] 2D/3D visualization software and internet entrepreneur

- Viatcheslav Mukhanov – contributor to the theory of cosmological inflation

- Sergey Nikolsky – mathematician

- Lev Okun - a Soviet theoretical physicist, who made contributions to the theory of elementary particles

- Lev Pitaevskii – theoretical physicist, who made contributions to the theory of quantum mechanics, electrodynamics, low-temperature physics, plasma physics, and condensed matter physics

- Valery Pokrovsky - is a Soviet and Russian physicist. He is best known for his pioneering and fundamental contributions to the modern theory of phase transitions

- Alexander Polyakov – quantum field theory classics,[34][35][36][37][38] Dirac'86[39] and Lorentz'94 Medals

- Emmanuel Rashba – Soviet-American theoretical physicist known for the Rashba effect and prediction of the Electric dipole spin resonance,[40] Lenin Prize

- Boris Rauschenbach – rocket scientist in control engineering, responsible for the first photographs of the far side of the Moon (1959)

- Mikhail Shifman – non-perturbative QCD classics,[41][42] Sakurai Prize (1999), Lilienfeld Prize (2006)

- Georgiy L. Stenchikov - applied mathematician

- Andrey A. Varlamov - an Italian physicist of Ukrainian origin, and the principal investigator at the Institute of Superconductors, Oxides and Other Innovative Materials and Devices (SPIN-CNR) in Rome

- Alexei Vasilievich Shubnikov - crystallographer and mathematician, who pioneered Russian crystallography and its application

- Rashid Sunyaev – an author of the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect and a model of black holes[43]

- Max Taitz - scientist, engineer, and one of the founders of Gromov Flight Research Institute

- Karen Ter-Martirosian – a theoretical physicist greatly contributed to high-energy physics

- Edward Trifonov - Russian-Israeli molecular biophysicist

- Misha Tsodyks - theoretical and computational neuroscientist

- Sergey Vavilov – a physicist, who founded the Soviet school of physical optics, known by his works in luminescence. In 1934 he co-discovered the Vavilov-Cherenkov effect, a discovery for which Pavel Cherenkov was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1958.

- Victor Veselago – put forward a theory[44] for metamaterials of the 21st century in 1967

- Grigory Volovik - theoretical physicist, who specializes in condensed matter physics. He is known for the Volovik effect.

- Vladimir Zakharov - mathematician and physicist, who is known for his contributions in nonlinear wave theory in plasmas, hydrodynamics, oceanology, geophysics, solid state physics, optics, and general relativity.

- Alexander Zamolodchikov – quantum field theory classics[35][37][45]

- Sergey Yablonsky - mathematician, one of the founders of the Soviet school of mathematical cybernetics and discrete mathematics.

Cosmonauts

- Yuri Baturin – cosmonaut (1998 and 2001 missions), former head of national security

- Aleksandr Kaleri – cosmonaut, spent 609 days on the Mir and ISS space stations

- Aleksandr Serebrov – cosmonaut, 373 days in outer space (four flights)

Political and business persons

- Alexander Abramov – founder of Evraz Group, #137 on the Forbes list

- Boris Aleshin – deputy prime minister in Russian government (2003–2004), president of AvtoVAZ (2007–2009), general director of TsAGI (2009–)

- Serguei Beloussov – businessman, entrepreneur, investor and speaker, founder of Acronis, executive chairman of the board and chief architect of Parallels, Inc.

- Aleksandr Frolov – CEO of Evraz Group, #390 on the Forbes list

- Valentin Gapontsev – fiber laser technology pioneer, founder of IPG Photonics

- Mikhail Kirpichnikov – Russian Science & Technology Minister (1998–2000), dean of Biology at MSU (2006–)

- Pavlo Klimkin – Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.[46]

- Alex Konanykhin – Entrepreneur, former banker, former Russian oligarch, with political asylum in the United States.

- Nikolay Kudryavtsev – rector of MIPT (1997–)

- Boris Saltykov – Russian Minister of Science and Technology (1991–1996)

- Natan Sharansky – Israeli Cabinet Minister (1996–2005), US Congressional Gold Medal (1986)

- Sergei Guriev – Economist, former rector of New Economic School (2004–2013)

- Volodymyr Shkidchenko – Defense Minister of Ukraine (2003–2004), four-star general of the Army

- Nikolay Storonsky – Russian-British founding CEO of British fintech company Revolut (2015–)

- Ratmir Timashev – American and Swiss businessman, entrepreneur, investor, co-founder and CEO of Veeam and Aelita Software Corporation, founder of ABRT Fund.

- Arkady Volozh – Kazakhstan-born Israeli technology entrepreneur, computer scientist, investor, and philanthropist

- Dmitry Zelenin – governor of Tverskaya Oblast (2004–2011)

- Dmitri Dolgov – Co-founder and CTO of the Google Self-Driving Car Project (Waymo) (2009–2021), then Co-CEO (2021–)[47][48]

References

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings-Emerging Europe & Central Asia". Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- 1 2 Moscow Institute of Physics & Technology

- 1 2 "Best Universities in the world". Mastersportal. Retrieved 20 Dec 2022.

- 1 2 "Best Universities". USNews. Retrieved 20 Dec 2022.

- 1 2 "Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT / Moscow Phystech)". Top Universities.

- ↑ "ShanghaiRanking-Univiersities".

- ↑ "Обращение Российского Союза ректоров 04.03.2022". Российский Союз Ректоров. March 4, 2022. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022.

- ↑ "Повесть древних времён или предыстория Физтеха", Ch 3 Archived 2006-10-11 at the Wayback Machine by N. V. Karlov.

- ↑ "Повесть древних времён или предыстория Физтеха", Ch 4 by N.V. Karlov.

- ↑ "Повесть древних времён или предыстория Физтеха", Ch 6 by N.V. Karlov.

- ↑ "Повесть древних времён или предыстория Физтеха", Ch 7 by N.V. Karlov.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "2006 Admission Statistics (in Russian)". Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Государственная академическая стипендия — Студенческая жизнь". mipt.ru.

- ↑ "Residence Prices".

- ↑ "Renaissance scientist with fund of ideas". Scientific Computing World. 15 July 2006.

- ↑ Gruntman, Mike (2022). My fifteen years at IKI, the Space Research Institute : position-sensitive detectors and energetic neutral atoms behind the Iron Curtain. Rolling Hill Estates, Calif.: Interstellar Trail Press. pp. 6–17. ISBN 9798985668704.

- ↑ "Summer Symposiums History". International Summer Symposium on Science and World Affairs. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ "Phystech's Educational Approach". Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Academicians, Hierarchy and Titles in Russian Science, MIPT Web Site". Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Shanghai Jao Tong University ranking methodology". Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "MIPT 2009 admittance statistics". Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1962 – Presentation Speech". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Kapitza P (1938). "Viscosity of liquid helium below the λ-point". Nature. 141 (3558): 74. Bibcode:1938Natur.141...74K. doi:10.1038/141074a0.

- ↑ "Press Release: The 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Ölander, A. "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1956: Award ceremony speech". nobelprize.org.

- ↑ "Press Release: The 2003 Nobel Prize in Physics". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1964 – Presentation Speech". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Intel Fellow – Boris A. Babayan". www.intel.com. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Bolibrukh AA (1995). 21st Hilbert Problem for Linear Fuchsian Systems. Amer Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-0466-9.

- ↑ Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M (1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature. 363 (6429): 558–61. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..558I. doi:10.1038/363558a0. PMID 8505985. S2CID 4254940.

- ↑ Gross DJ, Migdal AA (1990). "Nonperturbative two-dimensional quantum gravity". Phys. Rev. Lett. 64 (2): 127–30. Bibcode:1990PhRvL..64..127G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.127. PMID 10041657.

- ↑ Gubser SS, Klebanov IR, Polyakov AM (1998). "Gauge theory correlators from non-critical string theory". Phys. Lett. B. 428 (1–2): 105–14. arXiv:hep-th/9802109. Bibcode:1998PhLB..428..105G. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00377-3. S2CID 15693064.

- 1 2 Belavin AA, Polyakov AM, Zamolodchikov AB (1984). "Infinite conformal symmetry in two-dimensional quantum field theory" (PDF). Nucl. Phys. B. 241 (2): 333–80. Bibcode:1984NuPhB.241..333B. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(84)90052-X.

- ↑ Polyakov AM (1981). "Quantum geometry of bosonic strings". Phys. Lett. B. 103 (3): 207–10. Bibcode:1981PhLB..103..207P. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(81)90743-7.

- 1 2 Knizhnik VG, Polyakov AM, Zamolodchikov AB (1988). "Fractal structure of 2d—quantum gravity". Mod. Phys. Lett. A. 3 (8): 819–26. Bibcode:1988MPLA....3..819K. doi:10.1142/S0217732388000982.

- ↑ Polyakov AM (1977). "Quark confinement and topology of gauge theories". Nucl. Phys. B. 120 (3): 429–58. Bibcode:1977NuPhB.120..429P. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(77)90086-4.

- ↑ "Dirac Medallists 1986 — ICTP Portal". prizes.ictp.it. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ E. I. Rashba, Sov. Phys. Solid State 2, 1109 (1960)

- ↑ Shifman MA, Vainshtein AI, Zakharov VI (1979). "QCD and resonance physics: The ρ-ω mixing". Nucl. Phys. B. 147 (5): 519–34. Bibcode:1979NuPhB.147..519S. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(79)90024-5.

- ↑ Shifman MA, Vainshtein AI, Zakharov VI (1979). "QCD and resonance physics. Applications". Nucl. Phys. B. 147 (5): 448–518. Bibcode:1979NuPhB.147..448S. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(79)90023-3.

- ↑ Shakura NI, Syunyaev RA; Sunyaev (1973). "Black holes in binary systems. Observational appearance". Astron. Astrophys. 24: 337–55. Bibcode:1973A&A....24..337S.

- ↑ Veselago VG (1968). "The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and μ". Sov. Phys. Usp. 10 (4): 509–14. Bibcode:1968SvPhU..10..509V. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n04ABEH003699.

- ↑ Knizhnik VG, Zamolodchikov AB (1984). "Current algebra and Wess-Zumino model in two dimensions". Nucl. Phys. B. 247 (1): 83–103. Bibcode:1984NuPhB.247...83K. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(84)90374-2.

- ↑ Parliament appoints Klimkin as Ukrainian foreign minister, Interfax-Ukraine (19 June 2014)

- ↑ Bloomberg Profile: Dmitri Dolgov (20 July 2023)

- ↑ Computer History Museum: Profile - Dmitri Dolgov (20 July 2023)

External links

- Official website (in English)

- Official website (in Russian)