A bachelor is a man who is not and has never been married.[1]

Etymology

A bachelor is first attested as the 12th-century bacheler: a knight bachelor, a knight too young or poor to gather vassals under his own banner.[2] The Old French bacheler presumably derives from Provençal bacalar and Italian baccalare,[2] but the ultimate source of the word is uncertain.[3][2] The proposed Medieval Latin *baccalaris ("vassal", "field hand") is only attested late enough that it may have derived from the vernacular languages,[2] rather than from the southern French and northern Spanish Latin[3] baccalaria.[4] Alternatively, it has been derived from Latin baculum ("a stick"), in reference to the wooden sticks used by knights in training.[5][6]

History

From the 14th century, the term "bachelor" was also used for a junior member of a guild (otherwise known as "yeomen") or university and then for low-level ecclesiastics, as young monks and recently appointed canons.[7] As an inferior grade of scholarship, it came to refer to one holding a "bachelor's degree". This sense of baccalarius or baccalaureus is first attested at the University of Paris in the 13th century in the system of degrees established under the auspices of Pope Gregory IX as applied to scholars still in statu pupillari. There were two classes of baccalarii: the baccalarii cursores, theological candidates passed for admission to the divinity course, and the baccalarii dispositi, who had completed the course and were entitled to proceed to the higher degrees.[8]

In the Victorian era, the term "eligible bachelor" was used in the context of upper class matchmaking, denoting a young man who was not only unmarried and eligible for marriage, but also considered "eligible" in financial and social terms for the prospective bride under discussion. Also in the Victorian era, the term "confirmed bachelor" denoted a man who desired to remain single.

By the later 19th century, the term "bachelor" had acquired the general sense of "unmarried man". The expression bachelor party is recorded 1882. In 1895, a feminine equivalent "bachelor-girl" was coined, replaced in US English by "bachelorette" by the mid-1930s. This terminology is now generally seen as antiquated, and has been largely replaced by the gender-neutral term "single" (first recorded 1964). In England and Wales, the term "bachelor" remained the official term used for the purpose of marriage registration until 2005, when it was abolished in favor of "single."[9]

Bachelors have been subject to penal laws in many countries, most notably in Ancient Sparta and Rome.[3] At Sparta, men unmarried after a certain age were subject to various penalties (Greek: ἀτιμία, atimía): they were forbidden to watch women's gymnastics; during the winter, they were made to march naked through the agora singing a song about their dishonor;[3] and they were not provided with the traditional respect due to the elderly.[10] Some Athenian laws were similar.[11] Over time, some punishments developed into no more than a teasing game. In some parts of Germany, for instance, men who were still unmarried by their 30th birthday were made to sweep the stairs of the town hall until kissed by a "virgin".[12] In a 1912 Pittsburgh Press article, there was a suggestion that local bachelors should wear a special pin that identified them as such, or a black necktie to symbolize that "....they [bachelors] should be in perpetual mourning because they are so foolish as to stay unmarried and deprive themselves of the comforts of a wife and home."[13]

The idea of a tax on bachelors has existed throughout the centuries. Bachelors in Rome fell under the Lex Julia of 18 BC and the Lex Papia Poppaea of AD 9: these lay heavy fines on unmarried or childless people while providing certain privileges to those with several children.[3] In 1695, a law known as the Marriage Duty Act was imposed on single males over 25 years old by the English Crown to help generate income for the Nine Years' War.[14] In Britain, taxes occasionally fell heavier on bachelors than other persons: examples include 6 & 7 Will. III, the 1785 Tax on Servants, and the 1798 Income Tax.[3]

It has been noted by some people such as Francis Bacon that many preeminent men throughout history have been bachelors:[15]

He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises, either of virtue or mischief. Certainly the best works, and of greatest merit for the public, have proceeded from the unmarried or childless men, which, both in affection and means, have married and endowed the public.

Nikola Tesla also made a similar statement:[16]

I do not think you can name many great inventions that have been made by married men.

A study that was conducted by professor Charles Waehler at the University of Akron in Ohio on non-married heterosexual males deduced that once non-married men hit middle age, they will be less likely to marry and remain unattached later into their lives.[17] The study concluded that there is only a 1-in-6 chance that men older than 40 will leave the single life, and that after the age 45, the odds fall to 1-in-20.[17] Kenyan psychologist Florence Wamaitha noted that single men have the freedom to interact with people and hence have a deeper connection to the world and that most single males are financially stable as they do not have many family responsibilities.[18]

In certain Gulf Arab countries, "bachelor" can refer to men who are single as well as immigrant men married to a spouse residing in their country of origin (due to the high added cost of sponsoring a spouse onsite),[19] and a colloquial term "executive bachelor" is also used in rental and sharing accommodation advertisements to indicate availability to white-collar bachelors in particular.[20]

Men who never married

Listed chronologically by date of birth.

Gallery

Plato

Plato Jesus Christ

Jesus Christ Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci.jpg.webp) Michelangelo

Michelangelo Galileo

Galileo Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton David Hume

David Hume Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer Nikola Tesla

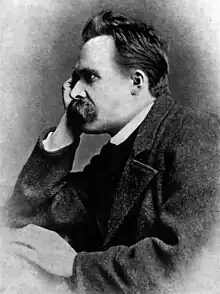

Nikola Tesla Frederich Nietzche

Frederich Nietzche The Wright Brothers

The Wright Brothers Alfred Nobel

Alfred Nobel Frederic Chopin

Frederic Chopin_crop-waist-slim.jpg.webp) Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky.jpg.webp) Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

Bachelorette

The term bachelorette[93] is sometimes used to refer to a woman who has never been married.

The traditional female equivalent to bachelor is spinster, which is considered pejorative and implies unattractiveness (i.e. old maid, cat lady).[93] The term "bachelorette" has been used in its place, particularly in the context of bachelorette parties and reality TV series The Bachelorette.[94]

See also

References

- ↑ Bachelors are, in Pitt & al.'s phrasing, "men who live independently, outside of their parents' home and other institutional settings, who are neither married nor cohabitating". (Pitt, Richard; Borland, Elizabeth (2008), "Bachelorhood and Men's Attitudes about Gender Roles", The Journal of Men's Studies, vol. 16, pp. 140–158).

- 1 2 3 4 Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "bachelor, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1885.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 196–197

- 1 2 Du Cange, Charles du Fresne, sieur (1733), Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinitatis (in Latin), vol. 1, pp. 906–912

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ For further etymological discussion, with sources, see Schmidt,(Schmidt, Uwe Friedrich, Praeromanica der Italoromania auf der Grundlage des LEI (A und B), Europäische Hochschulschriften; Vol. 49, No. 9 (in German)) reprinted by Lang.

- ↑ Schmidt, Uwe Friedrich (2009), "Praeromanica der Italoromania auf der Grundlage des LEI (A und B)", Italienische Sprache und Literatur (in German), Peter Lang, pp. 117–120

- ↑ Severtius, De Episcopis Lugdunensibus, p. 377 cited in Du Cange.[4]

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bachelor". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 132.

- ↑ "R.I.P Bachelors and Spinsters". BBC. 14 September 2005. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Plutarch, Lyc., 15.

- ↑ Schomann, Gr. Alterth., Vol. I, 548.

- ↑ Melican, Brian (2015-03-31). "Bizarre German birthday traditions explained". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ↑ Mellon, Steve (3 November 2016). "A tax on bachelors? Why not? 'There's one on dogs'". The Digs. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ Flatley, Louise (23 November 2018). "Men used to be Taxed if they Wanted to Remain a Bachelor". The Vintage News. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ Bacon, Francis. "Essays".

- ↑ Tesla, Nikola. "Goodreads".

- 1 2 McManis, Sam (January 26, 2003). "Kind of looking for Ms. Right / Older bachelors say freedom, high standards keep them single". SFGate. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ↑ Waithira, Nancy (27 November 2021). "What happens to men who stay bachelors for a lifetime?". Nation. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ↑ "Hundreds of 'bachelors' crammed in squalid and dilapidated buildings". GulfNews.com. 2009-05-03. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ↑ "executive-bachelor - Google Search". archive.is. 25 January 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013.

- ↑ Willis, Timothy M. Jeremiah – Lamentations (The College Press NIV Commentary) (College Press Publishing Co., 2002), 122.

- ↑ Targoff, Ramie. Posthumous Love: Eros and the Afterlife in Renaissance England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 59.

- ↑ Schoelcher, Victor. The Life of Handel, Vol. II (London: Robert Cocks & Co., 1857), 380.

- ↑ Guthrie, W. K. C. A History of Greek Philosophy, Vol. III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 36.

- ↑ Thomas, Joseph, M.D. Universal Pronouncing Dictionary of Biography and Mythology, Vol. II (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1908), 2396.

- ↑ Skinner, Hubert Marshall. The Schoolmaster in Comedy and Satire (New York: American Book Company, 1894), 129.

- ↑ Leigh, Aston. The Story of Philosophy (London: Trubner & Co., 1881), 31.

- ↑ Harris, Virgil McClure. Ancient, Curious and Famous Wills (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1911), 120.

- ↑ Davidson, Ian. Voltaire in Exile (London: Atlantic Books, 2004), 14.

- ↑ Cates, William Leist Readwin. A Dictionary of General Biography (London: Spottiswoode and Co., 1875), 890.

- 1 2 Becker, Thomas W. Eight Against the World: Warriors of the Scientific Revolution (Bloomington: AuthorHouse, 2007), 17.

- ↑ McElroy, Tucker, Ph.D. A to Z of Mathematicians (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2005), 25.

- ↑ Frischer, Bernard. The Sculpted Word: Epicureanism and Philosophical Recruitment in Ancient Greece (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 63.

- ↑ Parry, Emma Louise. The Two Great Art Epochs (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1914), 210.

- ↑ Phillipson, Nicholas. David Hume: The Philosopher as Historian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 12.

- ↑ Hazel, John. Who's Who in the Roman World (London: Routledge, 2001), 140.

- ↑ Timmons, Todd. Makers of Western Science (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012), 52.

- ↑ Anderson, John D. A History of Aerodynamics and Its Impact on Flying Machines (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 44.

- ↑ Rogers, Arthur Kenyon. The Life and Teachings of Jesus (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1894), 270.

- ↑ Rae, John. Life of Adam Smith (London: Macmillan & Co., 1895), 213.

- ↑ Lucian, Demoxan, c. 55, torn, ii., Hemsterh (Editor), p. 393, as quoted in A Selection from the Discourses of Epictetus With the Encheiridion (2009), p. 6.

- ↑ Allan-Olney, Mary. The Private Life of Galileo (Boston: Nichols and Noyes, 1870), 75.

- ↑ Paulsen, Friedrich. Immanuel Kant, His Life and Doctrine (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1902), 26.

- ↑ Smith, William, D.C.L., LL.D. (Editor). A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines (London: John Murray, 1887), 485.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (Editor). The Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes, Vol. I (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 191.

- ↑ Hubbard, Elbert. Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous Women (New York: William H. Wise & Co., 1916), 165.

- ↑ Green, Bradley G. (Editor). Shapers of Christian Orthodoxy (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 236.

- ↑ Williams, Henry Smith. The Historians' History of the World, Vol. XI (London: Kooper and Jackson, Ltd., 1909), 638.

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen, ed. (2007). God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs that Changed History. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 526. ISBN 978-0-7624-3004-8.

- ↑ Walker, Gabrielle. An Ocean of Air – Why the Wind Blows and Other Mysteries of the Atmosphere (Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc., 2007) 24.

- ↑ Rudall, H.A. Beethoven (London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company, 1903), 28.

- ↑ Cook, Terrence E. The Great Alternatives of Social Thought: Aristocrat, Saint, Capitalist, Socialist (Savage, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1991), 97.

- ↑ Sterling, Keir B. Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997), 465.

- ↑ Owen, William (Editor). A New and General Biographical Dictionary, Volume II (London: W. Strahan, 1784), 371.

- ↑ Bebel, August. Woman in the Past, Present and Future (San Francisco: International Publishing Co., 1897), 58.

- ↑ Bos, Henk J. M. Lectures in the History of Mathematics (American Mathematical Society, 1993), 63.

- ↑ "James Buchanan". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-12-19. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ↑ McElroy, Tucker, Ph.D. A to Z of Mathematicians (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2005) 24.

- ↑ von Hellborn, Dr. Heinrich Kreissle. Franz Schubert: A Musical Biography [abridged], trans. by Edward Wilberforce (London: William H. Allen & Co., 1866), 64.

- ↑ Bancroft, George. History of the United States of America, Vol. I (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1916), 561.

- ↑ Szulc, Tad. Chopin in Paris: The Life and Times of the Romantic Composer (Da Capo Press, 2000), 61.

- ↑ Francks, Richard. Modern Philosophy: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (London: Routledge, 2003), 59.

- ↑ Tibbetts, John C. Schumann – A Chorus of Voices (Amadeus Press, 2010), 146.

- ↑ Lasater, A. Brian. The Dream of the West, Part II: The Ancient Heritage and the European Achievement in Map-Making, Navigation and Science, 1487–1727 (Morrisville, NC: Lulu Enterprises, Inc., 2007), 509.

- ↑ Buber, Martin. "The Question to the Single One," from Søren Kierkegaard: Critical Assessments of Leading Philosophers, edited by Daniel W. Conway (London: Routledge, 2002), 45.

- ↑ Thomas, Joseph, M.D. Universal Pronouncing Dictionary of Biography and Mythology, Vol. II (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1908), 1814.

- ↑ Hudson, William Henry. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Herbert Spencer (London: Watts & Co., 1904), 23.

- ↑ Kidder, David S. The Intellectual Devotional Biographies: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Acquaint Yourself with the World's Greatest Personalities (New York: Rodale, Inc., 2010), 6.

- ↑ Mabie, Hamilton Wright. Noble Living and Grand Achievement: Giants of the Republic (Philadelphia: John C. Winston & Co., 1896), 665.

- ↑ Sandberg, Karl C. At the Crossroads of Faith and Reason: An Essay on Pierre Bayle (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1966), vii.

- ↑ Hubbard, William Lines (Editor), American History and Encyclopedia of Music, Musical Biographies, Vol. 1 (New York: Irving Squire, 1910), 97.

- ↑ Joesten, Castellion, and Hogg. The World of Chemistry: Essentials, 4th Ed. (Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2007), 25.

- ↑ Growe, Bernd. Degas (Cologne: Taschen GmbH, 2001), 35.

- ↑ Archibald, Raymond Clare. Semicentennial Addresses of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. II (New York, NY: American Mathematical Society, 1938), 272.

- ↑ Crumbley, Paul. Student's Encyclopedia of Great American Writers, Vol. II, 1830–1900 (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2010), 305.

- ↑ Salter, William Mackintire. Nietzsche the Thinker: A Study (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1917), 7.

- ↑ Heinich, Nathalie. The Glory of Van Gogh: An Anthropology of Admiration, trans. by Paul Leduc Brown (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 85.

- ↑ Brayer, Elizabeth (2006). George Eastman: A Biography. University Rochester Press. p. 3. ISBN 1-58046-247-2.

- ↑ Cheney, Margaret. Tesla: Master of Lightning (Metrobooks/Barnes & Noble, 1999), preface p. vi.

- ↑ Crouch, Tom D. The Bishop's Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright (W. W. Norton & Company, 2003)

- ↑ Garraty, John Arthur; Carnes, Mark Christopher; American Council of Learned Societies, American National Birography, Vol. I (London: Oxford University Press, 1999), 419.

- ↑ Burt, Daniel S. The Literary 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time, Revised Edition (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2009), 116.

- ↑ "″A Ophelinha pode preferir quem quiser″. Primeira carta de amor de Pessoa faz 100 anos". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). March 2020. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ↑ "BBC brings back Jim Corbett back to life with 75-minute documentary 'Corbett of Kumaon'". India Today. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ↑ Parachini, Allan (1986-02-18). "Jiddu Krishnamurti, 90, Indian Philosopher, Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Acharya Vinoba Bhave, who crusaded for a ban on... - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ↑ Danto, Arthur Coleman. Jean-Paul Sartre (Minneapolis: Viking Press, 1975), 166.

- ↑ "Homi Jehangir Bhabha | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ "'Why didn't you marry, President?'". The Times of India. February 2, 2006. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ↑ Konieczny, Vladimir. Struggling for Perfection: The Story of Glenn Gould (Toronto: Napoleon Publishing, 2004), 46.

- ↑ "Profile: Anna Hazare". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ↑ "Excerpt: Ratan Tata's Focus On Family Legacy Vs Marriage". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- 1 2 Eschner, Kat. "'Spinster' and 'Bachelor' Were, Until 2005, Official Terms for Single People". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-05-06.

- ↑ Gulla, Emily (2020-02-14). "The real meaning behind the word "spinster" and the secret ways it's still used today". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 2022-05-06.

External links

- Cole, David. "Note on Analyticity and the Definability of 'Bachelor'." Philosophy Department of the University of Minnesota Duluth. 1 February 1999.