|

| History of Sardinia |

The history of Phoenician and Carthaginian Sardinia deals with two different historical periods between the 9th century BC and the 3rd century BC[1] concerning the peaceful arrival on the island of the first Phoenician merchants[1][2] and their integration into the Nuragic civilization by bringing new knowledge and technologies, and the subsequent Carthaginian presence aimed at exploiting mineral resources of the Iglesiente and controlling the fertile plains of the Campidano.[3]

The Phoenicians

First Phoenician presences in Sardinia

During the 9th and 8th centuries BC there is news of their presence along the coasts of Sardinia. According to the most recent researches, the coastal Nuragic villages located in the southern and western coast of the island were the first points of contact between the Phoenician traders and the ancient Sardinians. These landings constituted small markets where the most varied merchandise were exchanged. With the constant prosperity of trade, the villages grew more and more, welcoming the exodus of Phoenician families fleeing from Lebanon. In this distant land they continued to practice their lifestyle, their own uses, their traditions and their cults of origin, bringing new technologies and knowledge to Sardinia.

Through mixed marriages and in a fruitful and continuous cultural exchange, the two peoples coexisted peacefully and the coastal villages became important urban centers, organized in a similar way to the ancient city-states of the Lebanese coasts. The first settlements arose in Karalis, Olbia, Nora (near Pula), Bithia, Sulki on the Sant'Antioco island, and Tharros on the Sinis peninsula, then in Neapolis near Guspini, and in Bosa.[4] At the same time as the prosperity of these coastal centers in Sardinia, on the other side of the Mediterranean, on the African continent, in 814 BC according to the classical tradition, Carthage was born, and sixty years later, in the Italian peninsula, Rome.[5]

Urbanism and writing

The Phoenicians introduced to Sardinia a form of urban aggregation hitherto unknown to the natives: the city. The Nuragic clans lived in cantons,[6] i.e. vast well-defined territories controlled by Nuragic towers located in strategic points. They were very skilled in designing and building complex defensive agglomerations and close to these, outside the walls, villages were located, ready to be evacuated in case of attack. Just as the Nuragics divided the island into cantons, so the now Sardo-Phoenicians organized the coastal villages in well-organized cities.

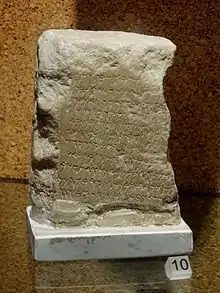

A sepulchral stele dated to the 9th century BC was found in Nora and preserved in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari;[7] according to many researchers, this stele is also the first testimony attesting to the written name used to name Sardinia. The toponym Shrdn[8] appears on the stele, without vowels as is customary in the ancient Semitic languages.[9]

Carthage

Military expansion of Carthage

Known for their prosperity, the city-states of Sardinia entered into Carthage's orbit of expansion. The nascent Punic colonial power, projected towards the conquest of the merchant routes in the western Mediterranean, was interested not only in controlling the territory of the coastal urban centers, but also the fertile plains of the interior, and above all the exclusive exploitation of the rich metal mines. A long war began which saw the Punics penetrate towards the inland territories.

In defense of Punic interests, in 540 BC Carthage sent an expert general to Sardinia, already victorious in Sicily against the Greeks and called Malchus (i.e. the King) by them. Having landed on the island with an expeditionary force made up of the Punic elites, with the task of freeing the coastal cities from the impending danger of annihilation, Malchus found the organized resistance of the Nuragic Sardinians.[10] Overwhelmed by continuous attacks and the guerrilla that developed around their movements, the Carthaginians were forced to retreat and re-embark suffering heavy losses.[10] The intervention of Carthage was described by the Roman historian Justin, and it seems that in the African motherland this defeat was described as a disaster, so much so that it subsequently motivated extensive civil and military reforms. After these events, the army was strengthened and became the symbol and instrument of the Carthaginian desire for domination.

After the victorious Battle of Alalia against the Phocaea Greeks, the Punics under the command of the two brothers Hasdrubal and Hamilcar, sons of Mago,[11] in 535 BC led a new military campaign for the conquest of the island. In 509 BC the Southern and Central-western portion of Sardinia was in the hands of Carthage.

Punic fortification system

The duration of the Punic presence in Sardinia is believed to be about 271 years, until the Roman invasion in 238 BC. During this period, the continuous wars were followed by a phase of settling, determined by the arrest of the Carthaginian penetration at the foot of the mountain massifs of the Barbagia and the ridge of the Goceano.

To defend against the indigenous people, a limes went from Padria to Macomer, Bonorva, Bolotana, Sedilo, Neoneli, Fordongianus, Samugheo, Asuni, Genoni, Isili, Orroli, Goni, Ballao to the mouth of the Flumendosa.[12]

Carthaginian coins found within the indigenous Sardinian territories suggest that despite the limes, trade exchanges existed between the two peoples.[13] The centers that stood near the border area were strengthened and new settlements were founded in inland areas.

End of Punic rule

In 368 BC the Sardinians, after almost 150 years of occupation, revolted against Carthage who sent his armies to the island to quell the uprising.[14]

In 238, after the First Punic War, the Romans, in the course of the Mercenary War, took control of Sardinia and Corsica who later become their second province after Sicily.

Gallery

Necropolis of Tuvixeddu, Cagliari

Necropolis of Tuvixeddu, Cagliari Tophet of Sulki

Tophet of Sulki Hypogeum at Monte Sirai

Hypogeum at Monte Sirai.jpg.webp) Terracotta statue of lion-headed man with gold and silver insets, 6th-5th century BC, from Tharros

Terracotta statue of lion-headed man with gold and silver insets, 6th-5th century BC, from Tharros Punic necklace from Olbia

Punic necklace from Olbia Stelae from Nora

Stelae from Nora

See also

References

- 1 2 SardegnaCultura.it, Fenicio-Punico

- ↑ SardegnaCultura.it,Il periodo precoloniale

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 35.

- ↑ Casula 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ Casula 1994, p. 83.

- ↑ Brigaglia 1995, p. 70.

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 15.

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 19.

- ↑ Murgia, Marco; Manuela Cuccuru. "Sardinia Point intervista Giovanni Ugas". www.sardiniapoint.it. Sardinia Point. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- 1 2 Barreca 1988, p. 33-34.

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 34.

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 86-88.

- ↑ Barreca 1988, p. 42.

- ↑ Casula 1994, p. 95.

Bibliography

- AA.VV, Storia della Sardegna, a cura di Manlio Briaglia, 1995

- AA.VV, La società in Sardegna nei secoli, ERI -Edizioni RAI, Radiotelevisione italiana, Torino 1967.

- F. Barreca, Il retaggio di Cartagine in Sardegna, Cagliari 1960.

- F. Barreca, La civiltà fenicio punica in Sardegna, Carlo Delfino Editore, Sassari 1988: in PDF:

- Francesco Cesare Casula, La Storia di Sardegna, Sassari, Delfino, 1994.

- G. Pesce, Sardegna punica, Fossataro, Cagliari 1960; riedizione Ilisso Edizioni, Nuoro 2000, ISBN 88-87825-13-0; in PDF:

- G. Pesce, Civiltà punica in Sardegna, Roma 1963.

- G. Lilliu, Rapporti tra civiltà nuragica e la civiltà fenicio punica in Sardegna, in Studi Etruschi.

- S. Moscati, La penetrazione fenicio-punica in Sardegna.

- Sabatino Moscati, Il simbolo di Tanit a Monte Sirai, in Rivista degli studi orientali, Roma 1964

- A. Succa, L'impero coloniale di Cartagine (Parte II, Capitolo II, La colonizzazione della Sardegna), Lecce-Roma, 2021.