Per Hasselberg (1 January 1850 – 25 July 1894), until 1870 Karl Petter Åkesson, was a Swedish sculptor. He has received critical acclaim mainly for his delicate and allegorical nudes, copies of which are widely distributed in public places and private homes in Sweden.

Biography

Hasselberg was born 1 January 1850 in the small village Hasselstad near Ronneby in the province of Blekinge in the south of Sweden.

He grew up as the sixth child in a poor family. His very religious father, Åke Andersson, was a small farmer, a construction worker for bridges, and a cabinet-maker.

Hasselberg finished school at the age of twelve and became a carpenter apprentice in Karlshamn, where he even got a training as ornamental sculptor. After this, he moved to Stockholm in 1869, where he took several jobs as ornamental sculptor and visited evening and weekend courses at craft school.

In 1876, he got a scholarship from the Swedish National Board of Trade to travel to Paris, where he was accepted at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts the following year. There, he studied for three years under the sculptor and academy professor François Jouffroy. He then worked as sculptor in Paris until 1890, when he returned to Stockholm to open a studio in Östermalm.

In 1885, he was taken in at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg because of aortic dissection. He recovered, but doctors told him he had only a few years to live.[1]

In 1894, his condition became serious again and he died 25 July in Stockholm at the hospital Sophiahemmet.[2]

At the time of his death, he had no debts and a book of orders of a total sum of about 30.000 Swedish Crowns,[3] which is equivalent to about 250.000 US-Dollar in 2015.[4] His will was that the large marble blocks, which were being shipped from Italy and which were destined for large copies of Farfadern and Näckrosen, should be handed over to his sculptor colleague Christian Eriksson to do the job (which he also did).[5]

Major works

Snöklockan (Snowdrop, Paris 1881)

The original French name was La Perce-Neige (snow breaker) and it was first made in plaster cast for the 1881 Salon in Paris. Hasselberg's model was 16-year-old Italian. At her feet shows a small snowdrop, and the statue was understood as a symbol of new life breaking through the snow in springtime.

Snöklocka actually is not the ordinary Swedish name for the flower, which is snödroppe. It is a rare poetic name that historically was derived from a literal translation of the ordinary German name Schneeglöckchen (little snowbell).[6] Thus a musical connotation was added by using it for the statue, and her right hand is close to her right ear.

The Snowdrop was not only accepted at the 1881 Salon, but even received an honorable mention, which no other Swedish work achieved that year. This success meant that he suddenly was a famous artist in Sweden, where the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm soon ordered a copy in marble. It was finished in 1883 and received a gold medal at the Salon in Paris the same year. In 1885, also the Gothenburg Museum of Art had its marble copy. The Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen/Denmark has one since 1889. Copies in bronze at public places are on Maria Square (Mariatorget)/Stockholm, in Falun, Ronneby, and near Sunne (Rottneros park).

1,700 pieces in parian ware (marble imitation) with a height of 50 cm and 625 pieces in 60 cm were produced in 1887-1926 by Gustavsberg porcelain.

The more recent reception of the Snowdrop in Sweden in the 21st century presented a new additive in the form of certain feminist views. One author of the catalogue of the large Hasselberg retrospective in Stockholm 2010 claimed that the closed eyes of the statue were not a sign of just waking up but rather showed that Hasselberg had “forced” the “body of the young woman” into a “state of unconsciousness”.[7]

Farfadern (Father’s Father, Paris 1886)

The original French name was L'Aiëul (The Grandfather) and it was first made in plaster cast 1886 in Paris and exhibited at the Palais de l'Industrie that year. The basic idea was to show nature's cycle containing the poles of young and old. It had its origin during Hasselberg's long treatment at university hospital in Gothenburg in 1885, after which he learned that he had only a few more years to live. He knew, therefore, that the planned work might be his last one and thus his artistic testament.

The idea became more definitive after he had seen an old man sitting with a naked sleeping boy on his knees on a boulevard in Paris. When it was finished, his artist friends were enthusiastic about it, but the exhibition in Paris was no success.[8]

The original copies in plaster cast by Hasselberg are lost, but a copy in bronze was placed near the National Library of Sweden in Stockholm 1896, and a copy in marble also from 1896 is today in the Gothenburg Museum of Art.[9]

Grodan (Frog, Paris 1889)

Grodan (French La Grenouille, English The Frog) was made in plaster cast for the Exposition Universelle (1889) in Paris and exhibited there. There is a frog between the knees of a girl. Hasselberg reported that the concept of this piece had spontaneously come up when a model in his studio during a break sat on the floor in this position to rest.[10]

The French word grenouille does not only mean frog but in slang also for street girl. It is unknown if Hasselberg was aware of this second meaning, but it was commented that by this statue, he possibly wanted to express his time's view of a tension between the noble and the less noble sides of youth.[11]

Several copies in bronze are in public parks in Sweden and marble copies in museums. The most recent bronze copy from 2009 in Ulricehamn replaced a stolen copy from the 1940s.[12] 230 pieces in parian ware (marble imitation) with a height of 38 cm and 241 pieces in 26 cm were produced in 1906-1926 by Gustavsberg porcelain.

Näckrosen (Water Lily, Stockholm 1892)

Näckrosen was first exhibited in plaster cast at the Danish art society Kunstforeningen in Copenhagen 1892 and later that year in Gothenburg/Sweden.[13] In 1893, it was exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The statue shows a young woman lying on her back, floating on a large water lily leaf, surrounded by water lilies, and heads of old men symbolizing mermen. The first part of the flower's name näck in Scandinavia means water spirit. So a literal translation of Näckrosen would be Water Spirit Rose. While this association is usually not present when talking about the flower, Hasselberg here made it unavoidable by the heads of old men in the water. On the backside of the statue, there is a tree stump that holds a chain with a large padlock, apparently indicating that the large water lily leaf was put on chain.

Gallery

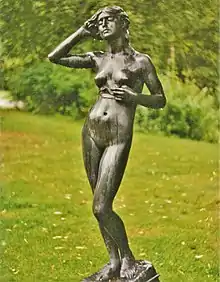

Tjusningen (Fascination) from 1880, since 1917 at Mariatorget in Stockholm.

Tjusningen (Fascination) from 1880, since 1917 at Mariatorget in Stockholm. Snöklockan, original in plaster cast from 1881 in the Town hall of Ronneby.

Snöklockan, original in plaster cast from 1881 in the Town hall of Ronneby. Snöklockan from 1885 in Fürstenbergska galleriet, Göteborgs konstmuseum.

Snöklockan from 1885 in Fürstenbergska galleriet, Göteborgs konstmuseum.

Ernst Josephson, in Fürstenbergska galleriet, bronze from 1883.

Ernst Josephson, in Fürstenbergska galleriet, bronze from 1883. Ernst Josephson, in bronze from 1883, among further copies in Nationalmuseum, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde and Thiel Gallery.

Ernst Josephson, in bronze from 1883, among further copies in Nationalmuseum, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde and Thiel Gallery. Såningskvinnan (Sower) from 1883 in Brunnsparken, Göteborg.

Såningskvinnan (Sower) from 1883 in Brunnsparken, Göteborg. Sven Adolf Hedlund from 1883 at Samhällsvetenskapliga biblioteket, Göteborg.

Sven Adolf Hedlund from 1883 at Samhällsvetenskapliga biblioteket, Göteborg.

Snöklockan in marble and six ceiling sculptures from 1895, Fürstenbergska galleriet, Göteborgs konstmuseum.

Snöklockan in marble and six ceiling sculptures from 1895, Fürstenbergska galleriet, Göteborgs konstmuseum. Farfadern since 1896 at Kungliga biblioteket, Stockholm.

Farfadern since 1896 at Kungliga biblioteket, Stockholm. Vågens tjusning (the wave's fascination), since 1920 in the park at Herrgårdsvägen on Hästö, Karlskrona.

Vågens tjusning (the wave's fascination), since 1920 in the park at Herrgårdsvägen on Hästö, Karlskrona. Vågens tjusning, from 1922 in the park at Vasakyrkan, Engelbrektsgatan, Göteborg.

Vågens tjusning, from 1922 in the park at Vasakyrkan, Engelbrektsgatan, Göteborg. Grodan from 1917 in Brunnsparken in Ronneby Brunn.

Grodan from 1917 in Brunnsparken in Ronneby Brunn. Grodan since 1949 in Grodparken, Ulricehamn.

Grodan since 1949 in Grodparken, Ulricehamn. Coco from 1953 in Rottneros Park.

Coco from 1953 in Rottneros Park. Näckrosen since 1912 in the park on Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm.

Näckrosen since 1912 in the park on Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm. Näckrosen in marble, Göteborgs konstmuseum.

Näckrosen in marble, Göteborgs konstmuseum. Näckrosen cast in bronze, Waldemarsudde, Stockholm.

Näckrosen cast in bronze, Waldemarsudde, Stockholm. Näckrosen detail, Göteborgs konstmuseum; chain and padlock on the left.

Näckrosen detail, Göteborgs konstmuseum; chain and padlock on the left.

References

- ↑ Lennart Wærn: Petter (Per) Hasselberg, Skulptör, Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Riksarkivet.

- ↑ Torell, Ulf (2007). Per Hasselberg: den nakna sensualismens skulptör (in Swedish). Ronneby: Ronneby hembygdsförening. pp. 14–25, 226, 283. ISBN 978-91-975092-3-7. OCLC 192057192.

- ↑ Torell, Ulf (2007). Per Hasselberg: den nakna sensualismens skulptör (in Swedish). Ronneby: Ronneby hembygdsförening. pp. 271–286. ISBN 978-91-975092-3-7. OCLC 192057192.

- ↑ Historical currency converter, by Rodney Edvinsson, associate professor, Stockholm University.

- ↑ Lennart Wærn: Petter (Per) Hasselberg, Skulptör, Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Riksarkivet.

- ↑ Lennart Waern: Natursymboliken hos Per Hasselberg, Tidskrift för konstventenskap 29, Uppsala 1952, p. 71-91, here 72-73.

- ↑ Jessica Sjöholm Skrubbe: Gränsfall: estetik och obcenitet i Per Hasselbergs skulpturer, in: Gunnarsson, Annika, et al (Eds) (2010). Per Hasselberg: Waldemarsuddes utställningskatalog. Malmö Stockholm: Arena/Åmells Artbooks Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde. ISBN 978-91-7843-325-4. OCLC 656365821.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), p.63-81, here p. 67. - ↑ Torell, Ulf (2007). Per Hasselberg: den nakna sensualismens skulptör (in Swedish). Ronneby: Ronneby hembygdsförening. pp. 143–145. ISBN 978-91-975092-3-7. OCLC 192057192.

- ↑ Gunnarsson et al (eds), Annika (2010). Per Hasselberg: Waldemarsuddes utställningskatalog. Malmö Stockholm: Arena/Åmells Artbooks Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde. p. 114 and 120. ISBN 978-91-7843-325-4. OCLC 656365821.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ↑ Torell, Ulf (2007). Per Hasselberg: den nakna sensualismens skulptör (in Swedish). Ronneby: Ronneby hembygdsförening. p. 174. ISBN 978-91-975092-3-7. OCLC 192057192.

- ↑ Lennart Waern: Natursymboliken hos Per Hasselberg, Tidskrift för konstventenskap 29, Uppsala 1952, p. 71-91, there p. 85-86.

- ↑ Skulpturer, website of the city of Ulricehamn (accessed 2019-12-17).

- ↑ Torell, Ulf (2007). Per Hasselberg: den nakna sensualismens skulptör (in Swedish). Ronneby: Ronneby hembygdsförening. pp. 241–247. ISBN 978-91-975092-3-7. OCLC 192057192.

- ↑ Planteringen i Kronbergs minne, Föreningen Kultur och Miljö i Falun.

External links

- Works by or about Per Hasselberg at Internet Archive

Media related to Per Hasselberg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Per Hasselberg at Wikimedia Commons- Hasselberg at Artfacts