| Penshaw Monument | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The monument | |

| Location | Penshaw, Sunderland, England |

| Coordinates | 54°52′59″N 1°28′51″W / 54.8831°N 1.48087°W |

| Elevation | 136 m (446 ft) |

| Height | 21 m (70 ft) |

| Built | 1844–1845[lower-alpha 1] |

| Architect | John and Benjamin Green |

| Owner | National Trust |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Earl of Durham's Monument |

| Designated | 26 April 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1354965 |

Location of Penshaw Monument in Tyne and Wear .svg.png.webp) Penshaw Monument (Sunderland)  Penshaw Monument (England) | |

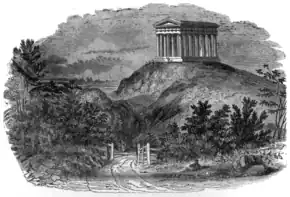

The Penshaw Monument (officially the Earl of Durham's Monument) is a memorial in the style of an ancient Greek temple on Penshaw Hill in the metropolitan borough of the City of Sunderland, North East England. It is located near the village of Penshaw, between the towns of Washington and Houghton-le-Spring in historic County Durham. The monument was built between 1844 and 1845[lower-alpha 1] to commemorate John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham (1792–1840), Governor-General of British North America and author of the Durham Report on the future governance of the American territories. Owned by the National Trust since 1939, it is a Grade I listed structure.

The monument was designed by John and Benjamin Green and built by Thomas Pratt of Bishopwearmouth using local gritstone at a cost of around £6000; the money was raised by subscription. On 28 August 1844, while it was partially complete, its foundation stone was laid by Thomas Dundas, 2nd Earl of Zetland in a Masonic ceremony which drew tens of thousands of spectators. Based on the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, it is a tetrastyle temple of the Doric order, with eighteen columns—seven along its longer sides and four along its shorter ones—and no roof or cella (inner chamber).

One column contains a spiral staircase leading to a parapeted walkway along the entablature. This staircase was closed to the public in 1926 after a 15-year-old boy fell to his death from the top of the monument. The structure fell into disrepair in the 1930s and was fenced off, then repaired in 1939. It has since undergone further restoration, including extensive work in 1979 during which its western side was dismantled. Floodlit at night since 1988, it is often illuminated in different colours to mark special occasions. The National Trust began to offer supervised tours of the walkway in 2011.

Penshaw Monument is a local landmark, visible from up to 80 kilometres (50 mi) away. It appears on the crest of Sunderland A.F.C. and is viewed nationally as a symbol of the North East. It has been praised for the grandeur, simplicity and symbolic significance of its design, especially when seen from a distance. However, critics have said it is poorly constructed and lacks purpose; nineteenth-century architectural journals condemned its lack of a roof and the hollowness of its columns and walls. It features no depiction of the man it honours, and has been widely described as a folly.

Location

Penshaw Monument stands on the south-western edge of the summit of Penshaw Hill,[2][lower-alpha 2] an isolated 136-metre (446 ft) knoll formed by the erosion of an escarpment of the Durham Magnesian Limestone Plateau.[7] The National Trust landholding at the site totals 18 hectares (44 acres),[8] including 12 hectares (30 acres) of deciduous woodland to the west of the monument.[2][lower-alpha 3] The woodland is split into Dawson's Plantation in the north and Penshaw Wood in the south.[2] Both the summit of the hill and the woodland are considered Sites of Nature Conservation Interest by Sunderland City Council.[2]

The monument's car park is accessible from Chester Road (the A183); three footpaths lead from the car park to the monument, which can also be reached from Grimestone Bank in the north-west and Hill Lane in the south.[2] The National Heritage List for England gives the monument's statutory address as Hill Lane,[3] but Sunderland City Council lists the property as located on Chester Road.[9] There have been few changes to the site since the monument's construction, although signs, fences and floodlights have been added, and footpaths have been improved by the National Trust.[10] There is an Ordnance Survey trig point to the west of the monument.[10]

The site receives over 60,000 visitors every year;[11] people come to visit the monument, admire the views or engage in walking, jogging or photography.[12] The Trust has placed a geocache at the site.[13] The Penshaw Bowl, an Easter egg rolling competition for children, takes place on the hill every Maundy Thursday;[14] this tradition is over a century old.[15] The hill is also popular for Bonfire Night and New Year celebrations.[5]

The surrounding area was formerly industrialised, but is now mainly arable farmland.[16] The site is in the Shiney Row ward;[17] it is south-west of Sunderland, north-east of Chester-le-Street, south-east of Washington and north of Houghton-le-Spring.[18] To the north is the Washington Wetland Centre, managed by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust; to the south is Herrington Country Park.[19] The monument is visible from 80 km (50 mi) away on a sunny day[20] and can be seen from the A1 road;[21] from the hill, it is sometimes possible to see the Cheviot Hills in Northumberland and the central tower of Durham Cathedral,[22] as well as the sea.[23]

History of the site

There is evidence that Penshaw Hill may have been an Iron Age hillfort: the remains of what may be ramparts have been identified at the site, and the expansive views from the hill would have made it a strategically advantageous location for a fort.[24] In March 1644, during the First English Civil War, the hill served as an encampment for an army of Scottish Covenanters who fled there after a failed attack on Newcastle before the Battle of Boldon Hill.[25] The hill is associated with the local legend of the Lambton Worm; a folk song written by C. M. Leumane in 1867 describes the worm wrapping itself "ten times roond Pensha Hill".[26][lower-alpha 4] The hill is the site of an 18th-century limestone quarry on Dawson's Plantation, which is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest;[27] farming and quarrying on nearby land continued after the monument's construction.[28]

The landholding is on the north-eastern edge of the historical township of Penshaw;[29] the original village of Old Penshaw is approximately 0.5 kilometres (0.31 mi) from the monument.[30] After Penshaw Colliery opened in 1792, a new pit village was established to the south-west of the original village – it was known as New Penshaw.[30] The earliest record of Penshaw is in the Boldon Book of 1183, where it is described as being leased by William Basset from a Jordan de Escoland, later Jordan de Dalton.[31] Other former landowners of the vill include the Bowes-Lyon and Lambton families.[31] The land on which the monument stands was eventually passed to the Vane-Tempest-Stewart estate and became the property of Charles Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, who gifted it as the site of the structure.[32][lower-alpha 5]

Conception and construction

Background

John George Lambton (born 1792) was the son of William Henry Lambton and Lady Anne Barbara Frances Villiers. He attended Eton College, then joined the 10th Royal Hussars in 1809. Lambton became Member of Parliament for County Durham in 1813; politically, he had a reputation for radicalism and proposing electoral reform, earning him the nickname "Radical Jack". In 1828 he was raised to the peerage, becoming Baron Durham. In 1830 Durham was made Lord Privy Seal in Earl Grey's cabinet and was charged with producing a draft of the bill that became the Reform Act 1832. He resigned his position in 1833, and was created Earl of Durham shortly afterwards. He was a Freemason and became Deputy Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England in 1834.[34]

The second Melbourne ministry appointed him Ambassador to Russia in 1835; he spent two years in the post. In 1838 Durham agreed to become Governor-General of British North America, and was sent to the British colony of Lower Canada (now Quebec) to deal with rebellions in the region. After a failed attempt to exile rebel leaders to Bermuda, he resigned from the post and left Canada after five months. His Report on the Affairs of British North America (1839) recommended that Lower Canada merge with the English-speaking province of Upper Canada to anglicise its French-speaking inhabitants; it also advocated limited self-government for the colony.[34]

After an illness lasting several months, thought to be tuberculosis, he died on 28 July 1840 in Cowes, Isle of Wight.[34] On 3 August, his body was taken in his own yacht to Sunderland, then in a steamship to Lambton Castle.[35] His funeral took place on 10 August, and was attended by over 300 Freemasons; they wanted to perform a Masonic ceremony for the occasion, but were asked not to do so by Durham's family.[36] The ceremony began at the castle, where the Earl lay in state in the dining room.[36] A procession, consisting of around 450 people in carriages and hundreds more on foot, then conveyed the body to the parish church of St Mary and St Cuthbert, Chester-le-Street, where Durham was buried in his family vault.[37] A large crowd gathered to observe the procession; its size has been estimated as between 30,000 and 50,000 people.[38] The Marquess of Londonderry, a political opponent of Durham's, travelled from London to act as a pallbearer at the funeral.[39]

1840–1842: proposals and selection of the site

At a meeting at the Lambton Arms pub in Chester-le-Street on 19 August 1840, it was decided to form a Provisional Committee to raise funds for a monument to the Earl by subscription.[40] The next day, at the Assembly Rooms in Newcastle, a committee of 33 men was formed for that purpose; it included the mayors of Newcastle and Gateshead.[40] The chairman of the committee was Henry John Spearman.[41] The following motion was put forward by William Ord MP:

That the distinguished services rendered to his country by the late John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, as an honest, able, and patriotic satesman, and as the enlightened and liberal friend to the improvement of the people in morals, education, and scientific acquirements, combined with his unceasing exercise of the most active benevolence, and of the other private virtues which adorned his character, render it the sacred duty of his fellow-countrymen to erect a public monument to perpetuate the memory of his services, his talents, and his virtues, and to act as an incitement to others to follow his bright example.[42]

Around £500 (equivalent to £48,000 in 2021) was pledged at this meeting. There were initially disagreements about the site of the monument: proposals included Durham, the Earl's territorial designation; Chester-le-Street, his burial place; Sunderland, where he had trading connections; and Newcastle, due to its size.[4] In a letter to the Durham Chronicle, published in October 1840, an anonymous subscriber to the monument urged that members of the public be allowed to submit designs, and that the final design be chosen by subscribers.[43] The letter warned of a "vicious system of jobbing" in which the exercise of private influence led to the adoption of inferior designs, which it claimed had influenced the planning of other monuments such as Nelson's Column.[43]

At another meeting at the Bridge Hotel in Sunderland on 28 January 1842,[44] William Hutt MP proposed that "the monument should be of an architectural character", and suggested Penshaw Hill as a location because it was the Earl's property,[lower-alpha 6] and the monument would be visible from much of County Durham and close to the East Coast Main Line.[45] Durham's wife had expressed support for this site before her death.[45] According to The Times, "a more suitable spot for the erection of a monument to the late lamented Earl could not have been selected".[46] Hutt hoped to erect a statue of Durham, and read out a letter from a sculptor who had offered to make one.[45] By this point, around £3000 (equivalent to £300,000 in 2021) had been subscribed.[45][lower-alpha 7] More money was later raised by a London-based committee.[47]

1842–1843: selection of the design

The committee sought advice from the Royal Institute of British Architects in London.[48] Its secretary, Thomas Leverton Donaldson, advised approaching five or six skilled architects named by the Institute privately, rather than advertising publicly for designs.[48] Donaldson told Hutt that if a public call for designs was made, the most skilled architects would not compete.[48] The Institute surveyed Penshaw Hill and produced instructions to the architects, which described the hill and indicated subscribers' preference for a column.[48] The instructions stated that the project could not cost more than £3000.[48] Six of the designs submitted to the committee were exhibited at the institute's premises in London before they were seen in the north.[49][50] These were all either columns or obelisks, each topped with a statue of the Earl.[50] At a meeting in Sunderland on 8 July 1842, subscribers examined proposals by seven architects.[48] These were:

- John Augustus Cory—Two designs: a column in the style of Italianate architecture; and a column based on those of the Temple of Hephaestus[lower-alpha 8]

- Thomas Leverton Donaldson—Design unknown

- Harvey Lonsdale Elmes—Two designs: a Grecian column topped by a temple containing an urn; and a column with projecting balconies in imitation of a Roman rostral column

- Charles Fowler—A Norman column, similar to those in the nave of Durham Cathedral

- Arthur Mee—A column; details unknown

- John Buonarotti Papworth—An obelisk, with a bronze statue and sarcophagus at the front

- Robert Wallace—A Doric column, 4.0 metres (13 ft) in diameter, based on those of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Agrigento and topped with a podium and a metal tripod[48]

Some present at the meeting were unhappy that the preference for a column had been expressed—one felt that "it would have been better to have left the genius of the artists unfettered", and another wished to receive more designs before a decision was made.[51] There was some consternation that the building of the monument was not taking place as quickly as had been anticipated.[51] The Durham Chronicle disapproved of the proposed designs, writing that "a column, standing in solitary nakedness, is a palpable absurdity".[52] It criticised the designs of Grey's Monument and Nelson's Column, believing them to belong to "the candlestick style of monumental architecture", and wrote that the monument to the Earl of Durham should be "lofty, massive, durable, and distinctive—simple in its features, and grand in its general effect".[52]

On 8 November 1842, an executive committee with the power to choose a design and begin construction of the monument was formed in Newcastle.[53] In May 1843, the committee met to consider new designs that it had received, and decided to recommend John and Benjamin Green's proposal of a Grecian Doric temple to subscribers.[54] By July, the design had been officially selected.[55] The Greens were father and son, and also designed Grey's Monument and the Theatre Royal in Newcastle.[23] The initial design was in the style of the temples of Paestum, with an arrangement of four by six columns; this was later changed to one based on the Temple of Hephaestus.[56][lower-alpha 9] It was envisaged that the hill would become an enclosed pleasure garden after the monument's construction.[56]

1844: construction and foundation stone ceremony

The stone used in the construction was a gift from the Marquess of Londonderry; it came from his quarries in Penshaw, about 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) from the hill.[46][lower-alpha 10] In a letter to subscribers, the Marquess explained his decision to provide the stone: "it has afforded me great satistfaction in a very humble manner to aid in recording my admiration of [the Earl of Durham's] talents and abilities, however I may have differed with him on public or political subjects".[58] Lime used in the construction was made in kilns owned by the Earl of Durham, located in the nearby village of Newbottle; sand was obtained from a sand pit at the foot of Penshaw Hill.[46] The materials were brought up the hill by a temporary spiral railway.[46] Holes on the stone blocks of the monument's stylobate indicate that they were transported with a lifting device called a lewis.[59]

In January and February 1844, an invitation to tender for the monument's construction was placed in the Durham Chronicle and Newcastle Courant newspapers.[60][61] The deadline to submit tenders was initially 15 February, but was later extended to 1 March.[60][61] By 15 March the builder Thomas Pratt of Bishopwearmouth, Sunderland, had been awarded the contract;[62] little is known about him.[63] By March, operations to clear the ground at the site had begun;[62] an invitation to tender for the transportation of the stone from the quarry to Penshaw Hill appeared in the Durham Chronicle on 29 March.[64] By May, a trench for the monument's foundations had been dug.[65]

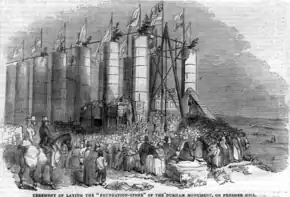

The foundation stone of the monument was laid on 28 August 1844 by Thomas Dundas, 2nd Earl of Zetland, Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England. The construction had been underway for several months:[46] all the columns had been built to around half of their final height, except two at the front of the structure.[56] The monument's scaffolding was adorned with flags for the ceremony.[66] The Great North of England Railway Company organised special trains from Sunderland, Newcastle, Durham and South Shields to bring spectators to the event, and galleries were erected on either side of the monument to allow them to watch the ceremony[46]—most of those in the galleries were women.[56] The Durham Chronicle estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 spectators were present;[66] the Durham County Advertiser reported at least 30,000.[56]

A pavilion was put up in a field to the south of Penshaw Hill to accommodate the Freemasons present,[46] including 400 members of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Durham.[23] At around 1:30 pm, the Freemasons formed a procession and ascended the hill, accompanied by a marching band and the monument's building committee.[67][lower-alpha 11] The Grand Treasurer placed a phial containing Victorian coins into a cavity in the foundation stone, which was then covered with a brass plate bearing an inscription that dedicated the monument to the Earl of Durham.[46][lower-alpha 12] Zetland then spread mortar on the stone with a silver trowel, specially engraved for the occasion.[46] A second stone was then lowered on top of it as the band played "Rule, Britannia!",[67] and Zetland used a plummet, level and square to adjust the upper stone before strewing it with corn, wine and oil.[46] The Reverend Robert Green of Newcastle said a prayer and the Freemasons examined the plans of the monument before returning to their pavilion as the band played "God Save the Queen".[46][67] The Times described the event thus:

[A] more animated and picturesque scene was perhaps never witnessed in this part of the country. ... The gorgeous insignia of the masonic brethren brilliantly reflected the rays of an almost vertical sun, the various banners fluttering in the gentle breeze, the gay dresses of the ladies, and the vast assemblage of spectators on every side, formed altogether a magnificent spectacle.[46]

That evening, two dinners were held in Sunderland to celebrate the event: one at the Wheatsheaf in Monkwearmouth and another at the Bridge Hotel.[56] The former was attended by many of the Freemasons who had participated in the ceremony; the latter accommodated many members of the gentry.[56] A dispute arose at one of these dinners when the vice-chairman, a Liberal solicitor called A. J. Moore, refused to take part in a toast in honour of the Marquess of Londonderry, a Tory.[69] Moore left the room, and the toast was drunk in his absence.[69] The Newcastle Journal condemned Moore's behaviour as a "brutal display of corrupt feeling, unmanly resentment, and base ingratitude".[69] In September 1844, one of the monument's architects threatened legal action against J. C. Farrow, who had announced the publication of a lithograph depicting the structure.[70] Green claimed that the monument—which was not yet finished—could not be depicted without reference to the architectural plans, and that the lithograph infringed his "rights of copy and design".[70] The Durham Chronicle called Green's claim "utterly preposterous and absurd".[70] In October, the Carlisle Journal reported that only one of the monument's columns had been topped with its capital, and that the structure was expected to be completed in 1845.[4] The total cost of the construction was approximately £6000 (equivalent to £638,400 in 2021).[19][71]

Subsequent history

1880s to 1920s: early damage and fatal accident

.jpg.webp)

On 29 May 1889, the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne was told of damage to the monument: many of the stones forming its stylobate had been removed and rolled down Penshaw Hill.[72] The stonework was repaired in the 1920s after it became cracked.[73]

It was once possible to pay a penny for the key to the staircase to the top of the structure.[74] This ended after a fatal accident:[74] on 5 April (Easter Monday) 1926, Temperley Arthur Scott, a 15-year-old apprentice mason from Fatfield, fell to his death from the top of Penshaw Monument.[75] There were around 20 people at the top when he fell.[75] He had ascended the structure with three of his friends; the group had climbed around the top twice and were attempting to do so a third time.[75] Scott tried to climb over a pediment to cross between the two walkways when he stumbled and fell 21 metres (70 ft).[14][75] A doctor pronounced him dead at the scene.[75] A police officer told an inquest at the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Fatfield that it was usual for people to visit the top of the monument on public holidays.[75] He said the stonework at the top of the pediment was worn, suggesting that many people had scaled it.[75] The deputy coroner declared a verdict of accidental death and recommended either that spiked railings be put on the pediments, or that the door to the staircase be permanently locked.[75] The door was kept locked from then on; after repeated break-ins it was sealed with cement, and later bricks.[74]

1930s to 1970s: National Trust restoration

At a conference organised by the Council for the Preservation of Rural England in Leamington Spa in summer 1937, J. E. McCutcheon of Seaham Town Council spoke about the need to protect tourist destinations in County Durham.[76] McCutcheon's comments interested B. L. Thompson, who was attending the conference on behalf of the National Trust; the two men began corresponding.[76] As a result, the Trust agreed to take over Penshaw Monument from John Lambton, 5th Earl of Durham on the condition that covenants be imposed on Cocken Wood, an area of woodland near Finchale Priory.[76] The monument became the Trust's property in September 1939.[20] In April 1950 it was classed as a Grade I listed building on the National Heritage List for England; its official name is the Earl of Durham's Monument.[3] Grade I buildings make up only 2.5% of listed buildings, and are described by Historic England as "of exceptional interest".[77]

In 1936 the Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette reported that multiple large stones had fallen from the monument and a fence had been erected around it[73]—the fence was wooden and covered in barbed wire, and was still there in 1938.[78] By July 1939 repair work was being carried out, and scaffolding was present around some of the monument's columns.[79] It was not damaged during the Second World War, despite raids on Houghton-le-Spring during The Blitz.[80] In 1942 it was struck by lightning; this caused damage to the top of the column containing the staircase.[81] This damage—a hole at the top of the column and a fissure extending half its length—was still visible a decade later.[74]

In 1951 the Sunderland Echo reported that children had unsealed the door to the staircase and climbed the monument to search for pigeons' eggs; the National Trust employed a local builder to reseal it.[82] In 1959 the National Coal Board repaired the monument after it was damaged by subsistence caused by mining: its northern, western and southern sides had become cracked, and part of the walkway had detached and overhung the interior.[83] Stone blocks were replaced with concrete slabs with stone facings.[83] Because of further settlement, Penshaw Monument was underpinned in 1978.[19] The next year the western side was taken apart, and damaged lintels were replaced with ones made of reinforced concrete;[19] the new lintels have buff-coloured artificial stone facings.[19]

1980s to 2000s: floodlighting and further repair

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

In 1982 a grant from the Countryside Commission allowed the National Trust to purchase 44 acres (18 ha) of land surrounding the monument,[23][80] including much of the south-facing side of Penshaw Hill and the woodland to the north-west.[8] The monument has been illuminated at night by floodlights since 1988, when Sunderland City Council paid £50,000 (equivalent to £143,000 in 2021) for them.[19] Between 1994 and 1996, several of these lights were stolen; Northumbria Police said they may have been used as grow lights for the cultivation of cannabis.[84] In 1994, The Journal reported that Penshaw Monument "might be sinking" after two surveys showed the levels of the bottoms of the columns were not even.[85] The National Trust hired the civil engineer Professor John Knapton to carry out a third, more comprehensive survey of the monument to assess whether movement had occurred.[85]

In 1996 the National Trust said it was spending over £100,000 (equivalent to £200,000 in 2021) to restore the monument.[86] Its columns and lintels had deteriorated and were repaired.[86] Its cast iron cramps had rusted, causing them to expand and stress the monument's stonework—these were replaced with stainless steel cramps bedded in lead.[86] Repointing was done using lime mortar made from lime quarried at the National Trust's pits on the Wallington estate in Northumberland.[86][lower-alpha 13] However, the surface of the stone, which has been blackened by soot, was not cleaned so that it would remain "a reminder of the area's tradition of heavy industry".[86] The Trust later said: "Now that mining has ceased, the blackness seems particularly evocative and proposals for cleaning have been resisted".[23] On 16 November 2005 a group of 60 volunteers, recruited by the National Trust from local businesses, universities and Boldon School, South Tyneside,[87] assisted with the upkeep of the monument by replacing the kissing gate at its entrance, building a plinth and path for its interpretation area, repairing and replacing the steps leading to it and planting 40 metres (130 ft) of hedge.[88]

2010s and 2020s: reopening of the staircase and vandalism

In August 2011 the National Trust opened the staircase to the public for the first time since 1926 and began to provide guided tours of the top of the structure.[89] More than 500 people attended the reopening, although only 75 were initially allowed to climb it; further tours took place in subsequent months.[89] The trust now normally provides tours every weekend between Good Friday and the end of September.[90] Tours last 15 minutes and only five people are allowed to go up at once; National Trust members can do so for free, but non-members must pay £5.[91] By March 2013, over 3600 people had taken the tours.[92]

In March 2014 the council announced that it would spend £43,000 to replace the floodlights[93] with 18 new energy-efficient LED lights, which it expected would save £8000 per year in operating costs; they produce a softer, whiter light than their predecessors, and can be programmed to illuminate the monument in different colours.[94] They were paid for with a government loan and were expected to reduce annual energy consumption from 75,000 kilowatt-hours to less than 10,000.[94] An archaeological watching brief was carried out during the lights' installation.[95] In April 2015 nine of the new lights, worth £20,000, were stolen; thieves used bolt cutters to breach the monument's security gates and open the lights' steel enclosures.[96] The installation was fully complete by August 2015.[94] The monument has since been illuminated in various colours to commemorate events, including the colours of the flag of France after the November 2015 Paris attacks;[20] the colours of Hays Travel in November 2020 to commemorate John Hays;[97] the colours of the Union Jack on 31 January 2020 to mark Brexit;[98] and blue on 24 March 2020 as a tribute to National Health Service and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.[99]

.jpg.webp)

On 26 July 2014, extensive areas of the monument were vandalised with red spray paint.[100] The graffiti included text and symbols related to the 2005 film V for Vendetta.[100] The National Trust said it had hired specialist contractors to remove the graffiti at a "considerable cost".[101] Although the Trust did not ask for donations, local residents and businesses gave £1500 to pay for the removal.[100] In 2019, as an April Fools' Day joke, it was announced that Penshaw Monument would be "moved stone by stone" to Beamish Museum in County Durham.[102] The museum claimed the move was due to "the discovery of an infestation of a rare breed of worm in Penshaw Hill"—a reference to the Lambton Worm legend.[102] In August 2019 the National Trust received £200,000 from Highways England's Environment Designated Fund.[11] It said it would use the money to provide better access to the monument by replacing old timber steps with new ones made of sandstone and limestone, and improve signage at the site using information from new ground surveys.[103] Repairs were also carried out on the monument itself, including stone repair and repointing on its stylobate.[103] It was originally proposed to add a new spur path, and ditches at the side of the main path with soakaway pits for drainage; however, these plans were abandoned, partly because of their archaeological impact.[104] As part of the Lumiere in Durham light festival in November 2021, the monument is to be illuminated with 140,000 separate points of light to commemorate the UK dead in the COVID-19 pandemic.[105]

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

Although it was intended as a memorial to the Earl of Durham, many sources describe Penshaw Monument as a folly;[106][107][108] it features no statue or sculpture of the man it was intended to commemorate.[109][lower-alpha 14] The monument was built in the style of a temple of the Doric order.[3] It is based on the Temple of Hephaestus, which is on the Agoraios Kolonos hill on the north-west side of the Agora of Athens.[111] The National Trust describes it as a replica of the temple;[112] however, according to the Sunderland Echo, "at best it could be said it is 'slightly similar to' the Temple of Hephaestus".[20][lower-alpha 15]

It is an example of Greek Revival architecture, which is rare in the historic County Durham.[1] The style first appeared there c. 1820 at country houses like Eggleston Hall; Penshaw Monument is a late example, as is Monkwearmouth Railway Station.[1] John Martin Robinson cites the monument alongside Bowes Museum as an example of the "eccentric buildings" found in the county.[115] Nikolaus Pevsner noted that the structure's proximity to the Victoria Viaduct produces a rare juxtaposition of Greek and Roman architecture.[1][lower-alpha 16] A booklet produced by Tyne and Wear County Council Museums compares Penshaw Monument to Jesmond Old Cemetery, whose gates were designed by John Dobson; it says that the monument "shares the Arcadian intentions of Dobson's Cemetery, but is very much more successful".[117] In her survey of the monument commissioned by the National Trust, Penny Middleton states that its "closest architectural and cultural relation" may be the National Monument of Scotland, an unfinished Grecian temple on Calton Hill in Edinburgh.[118]

Description

.jpg.webp)

Penshaw Monument is 30 metres (100 ft) long, 16 m (53 ft) wide and 21 m (70 ft) high,[19] making it the biggest structure serving only as a memorial in North East England.[119] It is made of gritstone ashlar,[3][19][lower-alpha 17] which was yellow at first, but has darkened.[119] The stone was originally held together by steel pins and brackets.[19] Graffiti is present on many areas of the monument, in the form of both carvings and ink.[119] Its foundations originally sat on limestone 6.1 m (20 ft) below the ground.[46] The base consists of the upper stylobate and the lower stereobate[120]—the columns sit on the stylobate, which is made of large gritstone blocks.[3][59] The height of the base varies from 1.23 m (4 ft 0 in) at the south-west corner to 2.35 m (7 ft 9 in) at the south-east.[120] When the monument was built there were no steps leading up to the stylobate.[121] The floor consists of setts,[59] which are pointed in mortar and laid to falls[lower-alpha 18] to diagonal flagstones.[122] These flagstones direct rainwater to a central gulley.[122]

The monument is a tetrastyle structure.[59] It has 18 tapered, unfluted columns:[119][123] seven along the north- and south-facing sides and four facing the east and west.[120] The columns are 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in) in diameter,[19] and 10 m (33 ft) high.[120] There are two parapeted walkways[lower-alpha 19] running from east to west at the top of the monument;[125] the parapets are 0.91 m (3 ft) tall.[126] One column—the second from the east on the south-facing side[127]—contains a 74-step[92] spiral staircase leading to the southern walkway.[14][125] The columns support a deep entablature, whose blocking course serves as the walkways;[46][124] the columns, and the walls of the foundation and entablature, are hollow.[lower-alpha 20] The entablature is made up of the architrave, frieze and cornice; the architrave and cornice are simple in design, and the frieze is adorned with triglyphs, although these are stylised and lack grooves.[59] There is a triangular pediment at each end of the entablature;[59] the total height of the entablature and pediments is 6.62 m (21.7 ft).[120]

.jpg.webp)

The structure has no roof,[3] leading The Illustrated London News to call it hypaethral;[128] however, The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal considered this adjective inappropriate.[106] It asserted that "[a]n 'hypoethral' temple does not mean one without any roof at all ... but only that peculiar kind of temple in which the cella was left partly uncovered"—the monument has no cella.[106] The Athenaeum called it "not only hypaethral, but hypaethral in issimo[lower-alpha 21]—and after the most extraordinary fashion", and remarked, "Possibly it was at first intended that there should be a roof, but in order to save expense, it was afterwards thought that such covering might be dispensed with".[124] According to the council, the monument was indeed originally intended to have a roof and interior walls but these were never built due to a lack of funding.[19] However, The Chronicle has reported that this is a myth and a roof was never planned.[110][lower-alpha 22]

Reception and impact

19th century

Before its completion, the Carlisle Journal said Penshaw Monument would be "one of England's proudest architectural wonders, and a fitting memorial of one of its wisest statesmen".[4] However, its design initially met with a hostile response in architectural circles: in 1844 The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal called it "as arrant a piece of 'nonsense architecture' as can well be imagined" and derisively compared it to a cattle pound.[106] The Art Union was similarly scathing: it was critical of the idea of a Greek temple, which it said "does not bespeak much of either invention or judgement". It concluded: "To us it appears to be one of the most absurd, ill-imagined, and ill-contrived things ever devised, utterly devoid of significancy, purpose, or meaning."[50]

The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal termed the presence of pediments despite the absence of a roof a "gross and palpable violation of meaning and common sense".[106] The Athenaeum was similarly critical of the roofless pediments—"the building will look as if there had originally been a roof to it, which had fallen in!"—and expressed disapproval of the lack of cella and inner walls, writing that the architects had "cut the Gordian knot" by omitting them.[124] The decision to make the walls and columns hollow was condemned by The Athenaeum, which called the structure "nearly as much a sham, as if it were composed of cast iron coloured in imitation of stone" and said it "may be intended as characteristic ... of an age which estimates plausible appearances above solid worth".[124] The Art Union agreed: the hollowness of the columns, it said, "partakes too much of sham construction, with little if any thing to recommend it on the score of economy".[50]

The Athenaeum wrote that climbing the monument's stairs could be dangerous,[124] and The Art Union condemned the staircase as "dreadfully narrow and inconvenient".[50] The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal believed that those who ascended the monument would "have to promenade somewhat after the fashion of crows in a gutter", and suggested that the architects ought to have provided a terrace on the roof of the monument, accessible by a wider staircase.[106] The Athenaeum expressed confusion at the absence of a statue or commemoration of the Earl of Durham, believing that "although it may not yet be definitely settled what it is to be, something must surely be intended".[124]

In 1850 The Times was more complimentary: "The position and architecture of this structure are both extremely fine, and viewed from the railway it produces the best effect."[130] At the Great Exhibition, which took place in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London in 1851, a model of the monument made of cannel coal was exhibited as part of the event's Mining and Metallurgy section.[131] In 1857 William Fordyce wrote: "The temple is remarkable for its grandeur, simplicity and imposing effect, nothing in the shape of ornament or meretricious decoration being introduced".[47] In his graphic novel Alice in Sunderland, which explores Lewis Carroll's connections to Sunderland, Bryan Talbot suggests that Carroll may have been inspired by the monument, comparing the door leading to the monument's stairs to a scene omitted from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), in which Alice knocks on a door in a tree.[132] In his 1887 story "The Flower of Weardale", author William Delisle Hay described the monument:

Upon the crest of a bare and ugly eminence that towers above the Wear, there stands a mighty experiment in stone: a Grecian temple, splendid and solemn, with its columns and entablatures, yet blackened and stained by the sooty atmosphere, and looming grandly through the rolling smoke-clouds rising from the collieries down below, over which it lords, and with which it has no fellowship. Queer art, curious taste, surely, which has raised this majestic memorial of an aesthetic age and clime, and planted it, severe and solid, here in the centre of the now most prosaic county of practical, toiling, prosaic England! A monstrous monument, set up a few decades ago in honour of some notability, dead and in spite of it forgotten! Yet may this modern Durham folly on Penshaw Hill emblematize the passage of the centuries, and serve, at any rate, to indicate to us a spot whereby there hangs a legend of elder England.[133]

20th and 21st centuries

The monument is often described by recent sources as a landmark which indicates to locals that they have returned home after a long journey;[17][23][134] it is no longer widely associated with John Lambton.[118] It is a key part of Sunderland's cultural identity,[135] frequently depicted by local photographers and artists.[129] Nationally, it is viewed as a symbol of the North East alongside the bridges of the River Tyne and the Angel of the North.[21] Sunderland A.F.C.'s current crest, adopted in 1997, features a depiction of Penshaw Monument; according to Bob Murray, the club's chairman at the time, it was included "to acknowledge the depth of support for the team outside the City boundaries".[136][lower-alpha 23]

In 2006 the monument featured alongside Hadrian's Wall and the Sage Gateshead in a television advertisement for the "Passionate People, Passionate Places" campaign, which was intended to promote North East England.[137] It was produced by RSA Films, a company founded by the directors Tony and Ridley Scott, both natives of the North East.[137] In 2007 the structure came second in a poll of places which inspired the most pride in residents of the region, behind Durham Cathedral and Castle;[138] in a survey conducted by the advertising company CBS Outdoor, 59% of people from Sunderland said Penshaw Monument was an important landmark.[139] It appears in Richard T. Kelly's 2008 novel Crusaders.[140] The National Trust has said that since it reopened the structure's staircase in 2011, "for some making it to the top has become a sort of personal pilgrimage, with many visitors finding it an inspiring and often quite emotional experience".[141]

Bryan Ferry, lead singer of the band Roxy Music, grew up in Washington, and often visited Penshaw Hill with his father.[142] He told The Times that the monument made a significant impression on him as a child, and seemed "like a symbol ... representing art, and another life, away from the coal fields and the hard Northeastern environment; it seemed to represent something from another civilization, that was much finer".[143] He has conceded, however, that the monument is "essentially a folly, a building without purpose".[142] In his book on Roxy Music, Michael Bracewell describes the experience of approaching the monument: "its immensity drawing nearer, the heroic ideal of the place falls away. Grandeur gives way to mere enormity, statement to silence, substance to emptiness. ... [T]his solid memorial ... was designed, like stage scenery, to be appreciated from a distance."[144]

Alan Robson called the monument "a striking example of Doric architecture" in an article for the Evening Chronicle.[145] The Independent's James Wilson thought it "perplexing" and a "seriously silly folly".[146] The Journal's Tony Jones called it "a visible but under-rated symbol of regional identity".[147] David Brandon described it in The Guardian as an "extraordinary ... symbol of the Earl of Durham's insanity and county pride".[148] The Northern Echo's Chris Lloyd compared Penshaw Monument to the Angel of the North, calling both "beautifully pointless".[149] Tony Henderson, also of The Journal, wrote that the lack of roof and interior walls "has been to the advantage of the monument as it allows the dramatic play of light among the columns".[23] In her Monument Guide to England and Wales, Jo Darke called the monument "a great northern landmark";[150] architectural historians Gwyn Headley and Wim Meulenkamp have described its blackened surface as "a satanic response to the pure white Hellenic ideal".[151] Nikolaus Pevsner wrote that "the monument looms as an apparition of the Acropolis under hyperborian skies".[1] In his book The Northumbrians, historian Dan Jackson praised it: "It is a building of great gravitas, and its austere Doric silhouette dominates the landscape for miles around."[108]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Most sources give the year of construction as simply 1844;[1][2][3] however, a Carlisle Journal article from October 1844 says that the monument was not finished, and would be completed in the following year.[4]

- ↑ "Penshaw" is often spelled Painshaw or Pensher in older sources.[5] Its etymology is uncertain, but it may be derived from the Celtic words *penn and *cerr, meaning "the head of the rocks".[6]

- ↑ The exact extent of the landholding is marked on the maps in Middleton 2010, between pp. 3–4 and 60–61.

- ↑ Middleton (2010, p. 18) suggests that the ramparts of the hillfort may have formed ridges on the hill which caused it to be associated with the legend of the worm. She compares the worm to the dragon in Beowulf and suggests it may have been conceived as the guardian of an ancient site located on the hill. In earlier versions of the legend, however, the hill in question is Worm Hill in the nearby village of Fatfield.[23]

- ↑ According to an 1848 tithe map, the hill officially remained the Marquess's property for a period after the monument's construction.[33]

- ↑ Although Hutt described Penshaw Hill as Durham's property, Middleton (2010, p. 25) writes that the hill itself was owned by the Marquess of Londonderry, and the Earl owned the land surrounding it.

- ↑ For a list of subscribers as of late 1840 and the amounts they gave, see Local Collections 1841, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ In older sources the Temple of Hephaestus is called the "Temple of Theseus" or the "Theseon".

- ↑ According to the Carlisle Journal, a design based on the Temple of Hephaestus was suggested by Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey,[4] former Prime Minister and Durham's father-in-law.

- ↑ A theory exists that some stones used in the construction came from a Roman river crossing at South Hylton—there is no evidence for this.[57]

- ↑ A full list of those who were part of the procession is given in Local Collections 1845, p. 102.

- ↑ For the full text of the inscription, see Local Collections 1845, p. 102. It has since been eroded; the National Trust has installed a brushed steel plaque on the monument bearing the same text.[68]

- ↑ The Times incorrectly writes that Wallington is in County Durham.

- ↑ There is a popular story that the statue of the Marquess of Londonderry in the market square in Durham was intended to be placed on top of Penshaw Monument; this is not true.[110]

- ↑ The monument is a similar size to the Temple of Hephaestus, but has a simpler design with fewer columns;[113] the temple has thirteen by six columns.[3] The monument's height is roughly double that of the temple, as is the diameter of its columns.[114]

- ↑ A third edition of the Pevsner Architectural Guides, County Durham: Buildings of England, coauthored by Martin Roberts with Nikolaus Pevsner and Elizabeth Williamson, was published in 2021. It has an illustration of Penshaw Monument on its cover and an entry for the monument on page 565.[116]

- ↑ Gritstone was chosen because local sandstone would not be durable enough to survive weather conditions on the hill.[59]

- ↑ "Laid to falls" means that the stones are on a slight slope to allow rainwater to drain along them.

- ↑ The walkways are called "promenades" in nineteenth-century sources.[106][50][124]

- ↑ According to Sunderland City Council, the 17 columns that do not contain the staircase are solid;[14] however, other sources agree that they are hollow.[47][119][124]

- ↑ In issimo means "to the greatest possible degree".

- ↑ There is a myth that the monument lacks a roof because the Earl of Durham increased his tenants' rent during its construction, causing them to refuse to build it.[59] In reality, construction began four years after his death.

- ↑ The monument is in the modern City of Sunderland district; the Sunderland Echo interprets this remark as a reference to its visibility from afar.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pevsner & Williamson 1983, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Middleton 2010, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Historic England. "Earl of Durham's Monument (Grade I) (1354965)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Leaves from a Note-Book: No. IV". Carlisle Journal. 12 October 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 6.

- ↑ Mills, A. D. (2011). "Penshaw". A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191739446. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 7, 9, 10.

- 1 2 Newman 2019, p. 2.

- ↑ "Penshaw Monument". MySunderland. Sunderland City Council. 2022. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 48.

- 1 2 Henderson, Tony (12 August 2019). "Help for one of the North East's most recognisable landmarks". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 51, 53.

- ↑ "Go geocaching at Penshaw Monument". National Trust. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Sunderland City Council 2015, p. 2.

- ↑ Davies, Hannah (13 April 2006). "Easter echoes of our Pagan past". The Journal. p. 46.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 7.

- 1 2 Fraser Kemp, MP for Houghton and Washington East (19 May 1997). "Home Affairs". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 436.

- ↑ Google (20 June 2020). "Penshaw Monument" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sunderland City Council 2015, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gillan, Tony (13 June 2020). "The story of Penshaw Monument – the real reason why Sunderland has a huge mock Greek monument on a hill and its links to the Freemasons". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 51.

- ↑ "Things to see and do at Penshaw Monument". National Trust. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Henderson, Tony (10 October 2005). "Well-loved historic tribute fit for a lord". The Journal. p. 18.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 15.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 17.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 4, 6.

- ↑ Newman 2019, p. 5.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 21.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 24.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 "Lambton, John George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15947. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Local Collections 1841, p. 27.

- 1 2 Local Collections 1841, p. 28.

- ↑ Local Collections 1841, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Local Collections 1841, p. 29.

- ↑ Local Collections 1841, pp. 28, 30.

- 1 2 Local Collections 1841, p. 38.

- ↑ "Monument to the Late John George, Earl of Durham". Newcastle Journal. 31 August 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "The Late Earl of Durham". The Times. 24 August 1840. p. 3.

- 1 2 "The Durham Monument". Durham Chronicle. 17 October 1840. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Durham Testimonial". Durham County Advertiser. 4 February 1842. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 Local Collections 1843, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Monument to the Late Earl of Durham". The Times. 30 August 1844. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Fordyce 1857, p. 567.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Late Earl of Durham's Monument". Durham Chronicle. 15 July 1842. p. 4. Retrieved 20 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Local Collections 1843, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Art Union 1844.

- 1 2 Local Collections 1843, p. 107.

- 1 2 "The Durham Monument". Durham Chronicle. 22 July 1842. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Local Collections 1843, p. 182.

- ↑ "The Durham Memorial". Newcastle Journal. 6 May 1843. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal 1843, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Monument to the Late Earl of Durham". Durham County Advertiser. 30 August 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ "The Marquis of Londonderry and the Durham Monument". Durham Chronicle. 21 June 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Middleton 2010, p. 47.

- 1 2 "Testimonial to the Late Earl of Durham". Durham Chronicle. 26 January 1844. p. 1 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Testimonial to the Late Earl of Durham". Newcastle Courant. 2 February 1844. p. 1 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Local Intelligence". Durham Chronicle. 15 March 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ "Testimonial to the Memory of the Late Earl of Durham". Durham Chronicle. 29 March 1844. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "The Lord Durham Memorial". Newcastle Journal. 25 May 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Laying the Foundation Stone of the Monument to the Late Earl of Durham on Pensher Hill". Durham Chronicle. 30 August 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 Local Collections 1845, p. 102.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 27, 59.

- 1 2 3 "The Durham Memorial and the Sunderland Banquet". Newcastle Journal. 31 August 1844. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Lord Durham's Monument". Durham Chronicle. 6 September 1844. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Harper 1922, p. 131.

- ↑ Society of Antiquaries 1891, p. 52.

- 1 2 "Penshaw Monument Damage". Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette. 2 September 1936. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 "Wearside Echoes". Sunderland Echo. 13 August 1953. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Penshaw Fatality". Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. 7 April 1926. p. 10 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Wearside Echoes". Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette. 19 October 1939. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". Historic England. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ↑ "Penshaw Monument—Danger Of Becoming a Ruin". Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette. 10 June 1938. p. 7 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Restoration". Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette. 22 July 1939. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ "Damage to Penshaw Monument". Sunderland Echo. 20 April 1942. p. 5. Retrieved 19 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "'Faux pas' by council". Sunderland Echo. 22 November 1951. p. 7 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Subsistence threatens Durham landmark". The Times. 19 October 1959. p. 12.

- ↑ Millar, Stuart (9 November 1996). "Church raid casts new light on skunk". The Guardian. p. 6.

- 1 2 Ffrench, Andrew (19 August 1994). "Monument may have that sinking feeling". Newcastle Journal. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Restored folly will stay a mucky monument". The Times. 8 August 1996. p. 18.

- ↑ "Landmark folly gets a makeover". The Northern Echo. 17 November 2005. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ "Monumental effort, please". The Journal. 26 October 2005. p. 52.

- 1 2 "Penshaw Monument opening: National Trust turns hundreds away". BBC News. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ "Take a stroll up Penshaw Hill". National Trust. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ "Tours to the top". National Trust. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- 1 2 Tallentire, Mark (20 March 2013). "Tours to top of Penshaw Monument". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ "New lights for Penshaw Monument". BBC News. 9 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Diffley, James (28 August 2015). "Penshaw Monument lit up by new £43,000 lighting scheme from Sunderland City Council". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ Nicholson 2015, p. 2.

- ↑ Henderson, Tony (23 April 2015). "Penshaw Monument floodlights stolen from iconic Wearside landmark". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ "Sunderland landmarks lit up in honour of travel firm boss". BBC News. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "The UK celebrates Brexit Day 2020, in pictures". The Telegraph. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Thompson, Fiona (26 April 2020). "Sunderland's landmarks lit up in blue in support for NHS and social care workers leading coronavirus battle". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Graffiti removed after donations". BBC News. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ↑ "Monument defaced with Vendetta signs". BBC News. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- 1 2 "Penshaw Monument to be relocated to Beamish! Update: April Fool!". Beamish Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- 1 2 "New project to improve access to Penshaw Monument". National Trust. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ Newman 2019, p. 7.

- ↑ Brown, Mark (18 November 2021). "'A chariot in the sky':Lumiere festival in Durham honours Covid dead". The Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal 1844, p. 373.

- ↑ Taylor, Louise (1 May 2015). "Folly of Sunderland contrasts starkly with efficiency of Southampton". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- 1 2 Jackson 2019, p. 101.

- ↑ Companion to the Almanac 1845, p. 225.

- 1 2 Seddon, Sean (26 November 2016). "Penshaw Monument: Was it supposed to have a roof? We look at the myths and legends". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ "Penshaw Monument". National Trust. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Middleton 2010, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ "Penshaw Monument". Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette. 5 June 1948. p. 2 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Robinson 1986, p. 93.

- ↑ Roberts, Pevsner & Williamson 2021, p. 565.

- ↑ Tyne and Wear County Council Museums 1980, p. 24.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Usherwood, Beach & Morris 2000, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Elevation survey examples: Penshaw Monument". AMR Geomatics. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ Newman 2019, p. 4.

- 1 2 RNJ Partnership 2019, p. 1.

- ↑ Pevsner & Williamson 1983, p. 371.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Athenaeum 1844, p. 836.

- 1 2 "Measured building survey examples: Penshaw Monument". AMR Geomatics. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ Henderson, Tony (26 August 2011). "Monumental views". Evening Chronicle. p. 23.

- ↑ "Topographical survey examples: Penshaw Monument". AMR Geomatics. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ Illustrated London News 1844, p. 149.

- 1 2 Middleton 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ "The royal progress to Scotland". The Times. 30 August 1850. p. 4.

- ↑ Hunt 1851, p. 18.

- ↑ Talbot 2014, p. 226.

- ↑ Hay 1887, p. 673.

- ↑ "More landmarks to show you're nearly home". BBC News. 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ Newman 2019, p. 6.

- ↑ "Sir Bob Murray recalls why he changed Sunderland AFC badge after 'sinking ship' ridicule". Sunderland Echo. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- 1 2 Rouse, Stephen (17 January 2006). "Film's top guns to put North name in lights". The Journal. p. 7.

- ↑ "Landmark tops region 'proud' poll". BBC News. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ "Mackem pride tops British". Sunderland Echo. 11 July 2007.

- ↑ Whetstone, David (27 December 2007). "North-East thrust into limelight". The Journal. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ "High times expected as monument opens again". The Journal. 27 March 2012. p. 3.

- 1 2 Ferry 2008.

- ↑ Bracewell, Michael (13 October 2007). "The birth of Roxy Music". The Times. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ↑ Bracewell 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Robson, Alan (22 February 1965). "You'll never feel lonely in this town". Evening Chronicle. p. III – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Wilson, James (13 June 1992). "A city red and white and proud all over – Britain's newest city, Sunderland". The Independent. p. 48.

- ↑ Jones, Tony (24 January 1994). "Folly's anniversary set to pass quietly". The Journal. p. 41 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Brandon, David (11 August 1997). "A cry for a lost childhood". The Guardian. p. 8.

- ↑ Lloyd, Chris (17 February 1998). "A heavenly host greets the Angel". The Northern Echo. p. 8.

- ↑ Darke 1991, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Headley & Meulenkamp 1999, pp. 221–222.

Bibliography

- "The Durham Testimonial". Art Union. London: Palmer and Clayton. 1844. p. 317.

- "The Durham Memorial Temple". Athenaeum. London: J. Francis. 1844. pp. 835–836.

- Bracewell, Michael (2008). Roxy: The Band That Invented an Era. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571229864.

- "Miscellanea". Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. Vol. 6. London: R. Groombridge. 1843. pp. 253–254.

- "Candidus's Note-Book: Fasciculous LIX". Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. Vol. 7. London: R. Groombridge. 1844. pp. 373–374.

- Companion to the Almanac (1845). The Companion to the Almanac; or, Year-Book of General Information for 1845. London: Charles Knight.

- Darke, Jo (1991). The Monument Guide to England and Wales: A National Portrait in Bronze and Stone. London: MacDonald and Co. OCLC 1008240876.

- Ferry, Bryan (2008). "Another Time, Another Place". In Bryson, Bill (ed.). Icons of England. London: Think Books. p. 94. ISBN 9781845250546.

- Fordyce, William (1857). The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham. Vol. 2. Newcastle: A. Fullarton and Co.

- Harper, Charles George (1922). The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. London: Cecil Palmer.

- Hay, William Delisle (1887). "The Flower of Weardale". Time. London: Swan Sonnenschein. pp. 672–685.

- Headley, Gwyn; Meulenkamp, Wim (1999). Follies, Grottoes and Garden Buildings. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 9781854106254.

- Hunt, Robert (1851). Synopsis of the Contents of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (5th ed.). London: Spicer Brothers.

- "Monument to the Late Earl of Durham". The Illustrated London News. Vol. 5. William Little. 7 September 1844. pp. 149–150.

- Jackson, Dan (2019). The Northumbrians: North-East England and Its People: A New History. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781787381940.

- Local Collections; or Records of Remarkable Events, Connected with the Borough of Gateshead. Gateshead: William Douglas. 1841.

- Local Collections; or Records of Remarkable Events, Connected with the Borough of Gateshead. Gateshead: William Douglas. 1843.

- Local Collections; or Records of Remarkable Events, Connected with the Borough of Gateshead. Gateshead: William Douglas. 1845.

- Middleton, Penny (2010). "Historic Environment Survey for the National Trust Properties in Tyne & Wear: Penshaw Monument". Archaeo-Environment Ltd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Newman, Mark (2019). "Heritage Significance and Impact Assessment [HISA]: Path relaying and repairs to the Monument, Penshaw Monument". Sunderland City Council. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2020. (Click the View icon next to "Heritage Significance Impact Assessment" to access the document.)

- Nicholson, Michael (2015). An Archaeological Watching Brief at Penshaw Monument, Chester Road, Penshaw, Sunderland (Report). Archaeological Research Services Ltd. doi:10.5284/1050246.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (1983) [1953]. The Buildings of England: County Durham. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300095999.

- RNJ Partnership (2019). "National Trust Penshaw Monument Revitalisation: Design and Access Statement". Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2020. (Click the View icon next to "Design & Access Statement" to access the document.)

- Roberts, Martin; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (2021). County Durham. The Buildings of England. New Haven, Connecticut and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300225044. OCLC 1225908677.

- Robinson, John Martin (1986). The Architecture of Northern England. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333373960.

- Society of Antiquaries (1891). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. South Shields: George Nicholson.

- Sunderland City Council (2015). "Local Studies Centre Fact Sheet Number 14: Penshaw Monument" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Talbot, Bryan (2014). Alice in Sunderland: An Entertainment. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics. ISBN 9780224080767.

- Tyne and Wear County Council Museums (1980). The Tyneside Classical Tradition: Classical Architecture in the North East, c. 1700–1850 (Booklet).

- Usherwood, Paul; Beach, Jeremy; Morris, Catherine (2000). Public Sculpture of North-East England. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0853236356.

External links

- Official website

- An early photograph of Penshaw Monument, taken c. 1910

.jpg.webp)