Passaconaway | |

|---|---|

| Papisseconneway | |

A 19th century representation of Passaconaway, Pennacook Sachem[1] | |

| Pennacook leader | |

| Preceded by | Nanepashemet |

| Succeeded by | Wonalancet (sachem) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | around 1570 near Merrimack River |

| Died | before 1669 |

| Relations | Montowampate |

| Children | 5, including Wonalancet[2] |

Passaconaway was a 17th century sachem and later bashaba (chief of chiefs) of the Pennacook people in what is now southern New Hampshire in the United States, who was famous for his dealings with the Plimouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies.

Name

17th century records spell his name in a variety of ways, including Papisseconewa, Papisseconeway, Passeconneway, Papisseconneway, Passeconewa, Passaconaway, and Peasconaway.[3] In New English Canaan (1637) Thomas Morton wrote the name as "Papasiquineo". At some point in the late 1830s American author Samuel G. Drake either theorized, or encountered someone else's theory, that these names are all derived from words for "child" and "bear" - he make the claim for the first time in the 1841 8th edition of his Indian Biographies. Chandler Potter's 1856 History of Manchester derived the name from papoeis "a child" and kunnaway "a bear", but does not provide citations for this (the two terms he uses most likely came from Roger Williams' A Key Into the Language of America, which includes papoòs "infant" and paukunnawaw "bear" and "Ursa Major"). The alleged "child of the bear" translation has become a staple in subsequent accounts about Passaconaway, but is linguistically problematic, despite looking plausible. Modern speculative reconstructions based on 17th century orthography point to the name most likely having been something (in modern orthography) like Papisseconneway. There are no extant contemporaneous accounts of the name's literal meaning, nor about whether it was related to his lineage, his status as a powow,[Note 1] or other social significance, whether it was an autonym or heteronym, or even from which of the various Algonquian languages it came (the English colonists were much better acquainted with Wampanoag, Massachusett and Narragansett communities than with the Pennacook, and Williams' glossary is of Narragansett words).

In 19th century and subsequent publications he has sometimes been equated with the Catholic sachem called St. Aspenquid, but this is erroneous.

Life

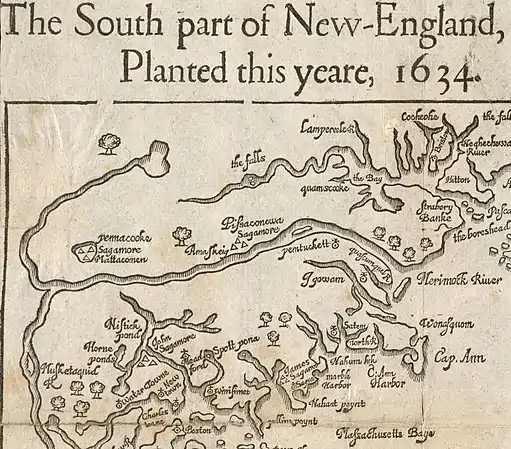

Passaconaway was widely respected by contemporaneous Native Americans in the New England region, by English colonists (even those who said that his supernatural abilities were satanic in origin), and was taken seriously as a political leader by colonial English settlers. One of the key native figures in the colonial history of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, he is believed to have been born between 1550 and 1570, and had died by 1669 (his birth and death dates are imprecise, and reckoning is skewed by the claim of one reporter, who says that he met Passaconaway when the latter was 120 years old). During his lifetime English colonial settlement in New England began in earnest, intersecting with an ongoing series of socio-political and demographic changes arising from warfare over the fur trade and the introduction of Eurasian diseases. In particular, an epidemic in 1616 ravaged the Native American populations in southeast New England, and that event's demographic consequences probably motivated sachems to allow the settlement of English colonists in their territories, usually under the framework of "land sales", to bolster their ability to engage in inter-group raids and warfare with other Native communities.

He was a powerful and widely respected powow (a ritual expert and mediator between humans and spirits similar to a shaman); English accounts by figures like Thomas Morton and John note that he was allegedly able to make water burn, produce ice in the summer, make trees dance, call up thunderstorms, make dried leaves turn green, and make living snakes out of dead snake skin.[6] Prior to, and during the early period of, colonial encroachment Passaconaway presumably followed traditional New England Native lifeways[7] in the Pennacook territories around the Merrimack River, moving among established village sites like Amoskeag and Pawtucket seasonally, which accounts for his historical association with several places in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Colonial records specify that Passaconaway lived at the top of the Pawtucket Falls (today's Lowell, Massachusetts). Local New Hampshire history says that he lived and moved seasonally among various fishing and planting spots along the Merrimack River, including the Amoskeag Falls in present-day Manchester, several fertile islands, present-day Horseshoe Pond, and sites along the nearby coast.

There are no records about the earlier part of his career beyond his reported abdication speech, which said that he had fought against the Mohawk as a younger man. At some point prior to the Pilgrims' arrival he became sachem (chief) of the Pennacook, and eventually bashaba (chief of chiefs) of a multi-tribal confederation in parts of today's New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Maine, members of which originally drew together for mutual protection from attacks by other Native groups. Passaconaway was one of the first native chieftains to lease land to English settlers in New England, and the 1629 Wheelwright Deed (the authenticity of which is debated, but which is generally accepted as legitimate) specifies that Passaconaway and other sachems were willing to sell territory to the English for the explicit purpose of making alliances against the Tarrantines (an exonym given to a confederation of Native groups in today's Maine which made a habit of attacking the groups in southeast New England) and the Mohawks. The English were problematic allies at best, and for the rest of his life Passaconaway repeatedly dealt with English transgression, affronts, and challenges to his autonomy.

In 1632, when a Native American murdered an English settler and fled, Passaconaway oversaw his capture and turned him over to colonial authorities. In 1642, when a rumor falsely claimed that there was an anti-English conspiracy developing among the local Native Americans, a militia was sent to apprehend Passaconaway and seize his guns. When the militia's forward progress was stopped by a thunderstorm, they instead seized his son, Wonalancet, his daughter-in-law, and his grandchild. When the authorities in Boston sent him an apology and invited him to come to the town to discuss the matter, Passaconaway insisted that the captives be freed. After they were, Passaconaway turned over his guns. In 1648 the English missionary John Eliot reported that he had gone to Pawtucket Falls, met Passaconaway, and preached to him there. According to Eliot, Passaconaway was receptive to his preaching, and invited him to come live with the Pennacook, which Eliot did not do. Whether Passaconaway converted is uncertain - no records indicate it, but legends among English colonists and their descendants maintained that he did. His son Wonalancet eventually became a Christian, and as his policies often continued his father's, it seems likely that Passaconaway was at least open to some form of Christian influence.

Passaconaway voluntarily abdicated in approximately 1660 and designated his second son Wonalancet as next sachem of the Pennacook (a position he actively held no later than 1664), which announcement was part of a larger speech he delivered urging his people to always keep peace with the English colonists. His larger family remained active in Native politics: his oldest son Nanamocomuck became sachem of the neighboring Wachusett.[8] His daughter Wanunchus married Montowampate, a sagamore of the Naumkeag in Saugus, who lived north of what is now Boston (their marriage was the topic of John Greenleaf Whittier's poem "The Bridal of Penacook"), and another daughter, known only as Bess, married Nobhow, the sachem of the Pawtucket.

In his old age Passaconaway, having relinquished his position of authority and having seen most traditional subsistence practices abandoned or rendered impossible by English colonial practices and laws, became dependent on the goodwill of the Massachusetts General Court and colonial government, petitioning in 1664 for a land grant for territory over which he once exercised some form of sovereignty.[9] In October 1665, Passaconaway's daughter, Bess (wife of Nobb How), sold the Pennacook territory called Augumtoocooke (present-day Dracut, Massachusetts) to Captain John Evered, for the sum of four yards of "Duffill" and one pound of tobacco. Capt. Evered in turn sold tracts of the land to European families for a great deal of money.[10] However, it is important to remember that by that time, the Pennacook and Pawtucket families had been arrested, harassed, enslaved, and shipped to Barbados in some cases.

The details of his death, including date, cause, and the location of his grave, are unknown. His son and successor, Wonalancet, kept to his father's policies regarding the English, including forbearing to take part in King Philip's War. His first son, Nanamocomuck, was the father of Kancamagus, who became Pennacook sachem after Wonalancet, and was far more inclined to fight back against the English than his grandfather and uncle had been. Kancamagus eventually removed the remnants of the Pennacook northward to the settlements along the Saint Lawrence River.

Passaconaway was later heroized by non-native New Englanders as a representative of a "good" Indian, largely due to his lifelong policy of nonaggression with the English colonists, the repeated positive comments on his character from English contemporaries such as John Eliot, and he has been commemorated in various places in New Hampshire and elsewhere.

Legends

Legends in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Maine are mostly drawn from, and elaborate upon, colonial accounts. Even before the Pilgrims' 1620 landing on the Massachusetts coast, a European ship's captain reported seeing a huge native standing atop a coastal cliff, surmising he was probably the native often referred to as Conway.

Another legend indicates that Passaconaway was summoned to the Plymouth area of Massachusetts by the Wampanoag sachem Massasoit, asking Passaconaway to use his supernatural powers to rid the land of the Pilgrims who were building a village on the shore (this is tied to versions of his abdication speech where he allegedly said he did everything to get rid of the English that he could - which does not line up with his lifelong policy of appeasement). At Massasoit's village, says the folklore, Passaconaway was for the first time in his life unable to bring up a storm. After conversing with the Great Spirit, Passaconaway declared that the Great Spirit had commanded him to live the rest of his life in peace with the white-faced tribes. From this time on, Passaconaway would not allow his sons or his tribe to fight with any European settlers, and counseled peace to all his native associates.

Local New Hampshire history says that in 1647 John Elliot attempted to speak with Passaconaway but was refused audience again and again before he was finally allowed to talk with the bashaba. Eventually the minister was invited to live with the Pennacook people and teach the elderly sachem about Christianity. Legend says that after the preacher died suddenly from an illness, Passaconaway decided to step down from his position of authority, announcing before an enormous crowd at the yearly native gathering that his son Wonalancet was now sachem of the Pennacook. This account closely follows the events narrated in Eliot's letter and descriptions of Passaconaway's farewell speech, but presents the two as somehow causally related.

The commemorative statue in Edson Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts is historically inaccurate - it depicts Plains Indian clothing and headdress. The other most frequently presented image of Passaconaway is a drawing that first appeared in Potter's History of Manchester, and has a somewhat better connection to period-accurate clothing, but the conspicuously displayed bearskin was almost certainly included due to the folk etymology of his name (discussed above).

Anglo-American legends about Passaconaway's death say that his body was buried in a cave in the sacred native mountain Agamenticus in southern Maine, and that at least one member of his people saw his spirit carried up to the Great Spirit's earthly abode of Agiocochook (Mount Washington) atop a sled pulled by wolves and covered with hundreds of animal skins given to him by his people and his fellow sachems. There he burst into flame and was carried up to the heavens to live with the Great Spirit. This legend is almost certainly due to Passaconaway being confused with St. Aspinquid, who was allegedly buried (without miracles) on Agamenticus. The details about wolf-drawn sleds and flaming translation are 18th and 19th century elaborations without any clear Native American antecedent.

Shortly before his death, Passaconaway was granted extensive tracks of land on both sides of the Merrimack as far north as the Souhegan River (although others, like Potter, have claimed without evidence that he settled in present-day Concord).[8] He most likely died and was buried near the island where he was last known to be living, in the Merrimack River not far north of the mouth of the Souhegan.

Village

The present-day Kancamagus Highway, a scenic two-lane highway through the White Mountains of New Hampshire, bears the name of Passaconaway's grandson, Kancamagus. The Kancamagus Highway passes the former village of Passaconaway, much of which is now part of the White Mountain National Forest. The village of Passaconaway once contained a sawmill, hotel and post office, as well as several farms and homes. For a few years a logging railroad ran through the area.[12] The short-lived Passaconaway Mountain Club was based there. The former settlement is located in the incorporated town of Albany, New Hampshire. Today the area is noted for its hiking and cross-country skiing trails. The U.S. Forest Service maintains the Passaconaway Campground and the Jigger Johnson Campground in this area, as well as the historic Russell-Colbath House and adjacent cemetery.[13]

Mountain

Mount Passaconaway, a 4,043-foot (1,232 m) summit in the Sandwich Range of the White Mountains lying between the village of Wonalancet and the Kancamagus Highway, bears the sachem's name.[14]

Legacy

The Daniel Webster Council of the Boy Scouts of America, which serves most of New Hampshire, honors Passaconaway by naming their Order of the Arrow lodge for the sachem.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Powow (also powwaw, pawaw, powah or powwow) is Algonquian for "shaman" and also for the public curing ceremony, purification ritual, or other rite performed or led by the shaman. By 1780 the English were using powwow as a verb meaning "to confer", but powwaw literally means "one who has visions".[4]

References

- ↑ Potter, Chandler Eastman (1856). The History of Manchester, Formerly Derryfield, in New Hampshire: Including that of Ancient Amoskeag, Or the Middle Merrimack Valley; Together with the Address, Poem, and Other Proceedings, of the Centennial Celebration, of the Incorporation of Derryfield; at Manchester, October 22, 1851. C.E. Potter. p. 52.

- ↑ Beals, Charles Edward (1916). Passaconaway in the White Mountains. Cornell University Library. Boston : R.G. Badger. p. 54.

- ↑ Hampshire., Potter, C. E. (Chandler Eastman), 1807-1868. History of Manchester, formerly Derryfield in New (2008). Master index to History of Manchester, New Hampshire, parts 1 & 2 by C.E. Potter 1856. Berkshire Family History Association. OCLC 501187191.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mary Ellen Lepionka, "Sachems and Shamans," in "History of Cape Ann and Beyond," at Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts, 2017-2022

- ↑ Wood, William, active (2009). Wood's vocabulary of Massachusett. Evolution Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-889758-97-8. OCLC 426796430.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Morton, Thomas (2001). New English Canaan. Ye Galleon Press. ISBN 0-87770-736-7. OCLC 46975008.

- ↑ Bragdon, Kathleen J. (1999). Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806131269.

- 1 2 Stewart-Smith, David (1998). The Pennacook Indians and the New England frontier, circa 1604–1733 (Thesis). ProQuest 304504354.

- ↑ Lyford, John (1896). History of Concord, New Hampshire. p. 72.

- ↑ History of Dracut, Massachusetts, called by the Indians Augumtoocooke and before incorporation, the wildernesse north of the Merrimac. First permanent settlement in 1669 and incorporated as a town in 1701. Silas Roger Coburn (1922)

- ↑ Jones, Leslie, Passaconaway Indian statue in Lowell Edson Cemetery, retrieved 2022-10-31

- ↑ Beals, Charles Edward, Jr., Passaconaway in the White Mountains (Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916). The author was a summer resident of the village, and later a ranger in the White Mountain National Forest. The title of the book refers to the village, not to the Pennacook leader (who had no known connection to the White Mountains).

- ↑ WMNF official website

- ↑ "Hiking Mount Passaconaway - Appalachian Mountain Club". www.outdoors.org.

- Beals, Charles Edward, Jr., Passaconaway in the White Mountains (Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916)

- Carter, George Calvin, "Passaconaway: The Greatest of the New England Indians" (published transcript of 1947 speech) (Manchester, NH: Granite State Press, 1947)

- Drake, Samuel Adams, "St. Aspenquid of Agamenticus," A Book of New England Legends and Folk Lore (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884), pp. 359–362

- Lyford, James O., ed., History of Concord, Vol I (Concord, NH: The Rumford Press, 1903)

- Potter, C. E., The History of Manchester (Manchester, NH: C. E. Potter, 1856)