| Palace of Venaria | |

|---|---|

Reggia di Venaria Reale | |

.jpg.webp) View of the Palace | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| General information | |

| Location | Venaria Reale, Metropolitan City of Turin, Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°8′8.99″N 7°37′24.67″E / 45.1358306°N 7.6235194°E |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 80,000 m2 (861,112 ft2)[1] |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Official name | Reggia di Venaria Reale - Residences of the Royal House of Savoy |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, vi, v |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 823 |

| Region | Europe |

The Palace of Venaria (Italian: Reggia di Venaria Reale) is a former royal residence and gardens located in Venaria Reale, near Turin in the Piedmont region in northern Italy. It is one of the Residences of the Royal House of Savoy, included in the UNESCO Heritage List in 1997.

The Palace was designed and built from 1675 by Amedeo di Castellamonte, commissioned by duke Charles Emmanuel II, who needed a base for his hunting expeditions in the heathy hill country north of Turin. The name itself derives from Latin, Venatio Regia meaning "Royal Hunt". It was enlarged to become a luxurious residence for the House of Savoy. The palace complex became a masterpiece of Baroque architecture and was filled with decoration and artwork. It fell into disuse at the end of the 18th century. After the Napoleonic wars, it was used for military purposes until 1978, when its renovation began, leading to the largest restoration project in European history. It opened to the public on October 13, 2007, and it has since become a major tourist attraction and exhibition space.

It is noted for its monumental architecture and Baroque interiors by Filippo Juvarra, including the Galleria Grande and its marble decorations, the chapel of Saint Uberto, and its extensive gardens. It received 1,048,857 visitors in 2017, making it the sixth most visited museum in Italy.[2]

History

17th century structure

Charles Emmanuel II was inspired by the example of the Castle of Mirafiori, built by Duke Charles Emmanuel I for his wife Catherine Michaela of Spain. Keen to leave a memorial of himself and his wife, Marie Jeanne of Savoy-Nemours, he bought the two small villages of Altessano Superiore and Altessano Inferiore from the Milanese-origin Birago family, who had employed the land for agricultural use. The place was rechristened Venaria for its future function as a hunting base (Venatio, in Latin). The construction of this residence fell in the larger plan of surrounding the city of Turin with a garland of delicacies (Corona di Delizie), a system of palaces and leisure residences which included the Palazzina di caccia of Stupinigi, Castle of Rivoli, Villa della Regina, and others.

In 1658 Charles Emmanuel commissioned the project of the palace and the new town built around to architect Amedeo di Castellamonte.[3] The plan envisioned a grandiose ensemble of a palace, gardens, hunting woods, and a new town, bearing a noteworthy scenographic impact. The new town's plan was circular to reflect the round shape of the collar of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, a dynastic order created by the House of Savoy. Construction began in 1659 and under the direction of Amedeo di Castellamonte work proceeded steadily, starting with the stable and the clock tower in 1660. The Palace of Diana, functioning as the central body of the palace and intended to house the duke and the court, was built in successive phases: it was first built on two levels with short side loggias and subsequently raised bu adding two more floors, the topmost of which was intended as a belvedere, between 1660 and 1663. It was then modified with the creation of apartments more suitable for private life, of smaller dimensions compared to the halls and parade chambers of the central body. The building was further expanded with the creation of pavilions facing the gardens in 1669 and of small pavilions that close off the courtyards on both sides of the palace in 1671. The facade was built with a loggia on the first floor flanked by grand arched entrances, the left one of which was subsequently destroyed during the renovations of Garove. The layout of the plan, consisting of a main compact block volume denote the influence of late sixteenth-century Roman works, such as the layouts of Villa Borghese and that of Villa Mondragone.[4][5]

Castellamonte also built the loggia and theater in the upper garden (1666), the square in front of the palace (1667), the twin facades of the churches in the town square (1669), the citroneria and the fountain of Hercules, the avenue of the fountain of Hercules (1671), the temple of Diana in the gardens (1673), the porticos of the central street of the town (1679). The entire complex was tied together by the straight axis that cut across the town, reached the heart of palace, followed the canal and arrived to the fountain of Hercules and finally the temple of Diana in the gardens.

18th century additions

After the French destroyed some buildings on 1 October 1693 (fighting the Savoys as part of the Nine Year's War), Duke (future King of Sardinia) Victor Amadeus II had the residence modified according to French canons, with the intent of rivaling the Palace of Versailles. Starting in 1699, he entrusted the project to its new director and Michelangelo Garove, who followed Victor Amadeus' intent of building an ever more grandiose palace. Garove's plan envisioned a complete reimagining of the palace according to contemporary standards. The Reggia di Diana would be flanked by two enormous wings, one south and one north of it, with pavilions at each end. He constructed the south-west pavilion (1702), the south-east pavilion (1703-1713) and he began the Great Gallery connecting them, which would remain unfinished with his death in 1713. The two pavilions, connected by the Gallery, constituted the south wing of Garove's plan, but the north wing was never built. The palace gardens were redesigned to conform to the French formal style, with views and perspectives continuing out to infinity on the model of the Palace of Versailles, which at the time was considered the ideal royal residence.[6] Garove's plans for this expansions were sent to be examined by Robert de Cotte, the architect of the French court. In the gardens Garove demolished the Temple of Diana (1700), traced the Allea Reale and extending the avenue (1702), demolised the seventeenth-century citroneria (1703), traced the English Garden (1710), built the Green Apartments and demolised the seventeenth-century Loggia Theater (1711).

Further damage was inflicted during the Siege of Turin (1706), when the French troops under Louis d'Aubusson de La Feuillade were garrisoned there. After the Savoyard victory, Victor Amadeus entrusted Filippo Juvarra in 1716 to enlarge the palace. Juvarra completed the Great Gallery (1716), set up the south-east pavilion, built the Citroneria and the Scuderia Grande (1722-1727), and built the chapel of Sant'Uberto. In the gardens, Juvarra demolished the remaining foundations of the temple of Diana in 1719 and in 1725 built the Labyrinth and its pavilion. He oversaw the renovation in French-style of the facades, elevating the palace to a Baroque masterpiece.

In 1739, Charles Emmanuel III hired new director Benedetto Alfieri with the task of building connective structures across the still disjointed wings of the palace and other functional spaces. Alfieri demolished the clock tower and rebuilt it in the same place (1739), erected the Belvedere wing (1751), the gallery between the chapel and the Citroneria (1754), the small western stable (1758) and the eastern one (1760 ), and the indoor riding halls (1761). In 1788-89 architects Giuseppe Battista Piacenza and Carlo Randoni created the staircase on the facade of the Reggia of Diana and decorated according to the neoclassical taste the new apartments on the first floor intended for the dukes of Aosta, putting an end to the architectural history of the complex.[7] In the 18th century the Palace was overlooked in favor of the Palazzina di Caccia di Stupinigi (1729), which was by then more in tune with the tastes of the European courts. The Palace continued to serve under the reigns of Victor Amadeus III and Charles Emmanuel IV.[7]

Military use and abandonment

In 1792, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the other states of the Savoy Crown joined the First Coalition against the French First Republic, but was beaten in 1796 by Napoleon and forced to conclude the disadvantageous Treaty of Paris (1796), giving the French army free passage through Piedmont. On 6 December 1798 Joubert occupied Turin and forced Charles Emmanuel IV to abdicate and leave for the island of Sardinia. The provisionary government voted to unite Piedmont with France. In 1799 the Austro-Russians briefly occupied the city, but with the Battle of Marengo (1800), the French regained control. During the Napoleonic domination, the structures of the palace were turned into barracks and the gardens were destroyed to create a training ground. The palace suffered irreversible damage during the Napoleonic period.[8]

Because of the heavy damage sustained during the French occupation, once Napoleon was defeated and the Kingdom of Sardinia restored, the palace of Venaria did not revert to its previous role as royal residence, but became a Royal Military Domain (Regio Demanio Militare). The decors and furnishing that could be salvaged were transferred to the other palaces and castles of the Savoy court, and the role of royal summer residence was taken up by the castle of Racconigi, that of Stupinigi, and that of Agliè.[7]

During its role as a military structure, which included being part of the Demanio Militare between 1851 and 1943, the complex was used Italian Army. iI housed the Field Artillery Regiment "a Cavallo", the Regia Scuola Militare (today Scuola di cavalleria dell'Esercito Italiano), and the 5th Field Artillery Regiment from 1850 to 1943. In the early 1900s the military started slowly abandoning the site, and the property gradually was transferred to the Ministry of Culture, starting in 1936 with the Chapel.

Restoration

Once the military garrison was removed, the palace became prey to vandalism and continued on a slow and inexorable abandon. Given the lack of funds for the site, the interventions of the Ministry of Culture were minimal and essential and aimed at the preservation of the structural integrity of the buildings. A small scale restoration of the Chapel was undertaken in the 1940s.[9]

In 1961, in occasion of the celebration of the 100th Anniversary of the Unification of Italy, the Great Gallery and the Hall of Diana were briefly restored, albeit in a mostly scenographic manner.[7] In the 1960s a group of Venariese citizens gave life to the Coordinamento Venariese per la Tutela e Restauro del Castello (Venariese Coordination for the Protection and Restoration of the Castle), which started some limited work to restore and highlight the decaying palace.

Starting in the 1980s, funds from the FIO (fondi di investimento occupazionale) were employed for early work of redevelopment, restoration and enhancement aimed at raising public awareness.

On 5 December 1996, the Minister for Culture Walter Veltroni, in agreement with the President of Piedmont Enzo Ghigo, gave birth to the "Committee for the Reggia di Venaria", which started the long process of restoration of the Palace. In 1999 the first framework agreement was signed the Ministry of Culture, the Piedmont Region, the City of Turin, and the municipalities of Venaria Reale and Druento. Overall the work lasted 8 years from 1999 to 2007, and was the largest restoration project in European history. The project involved 700 technicians and collaborators and 300 companies for a total of over 1,800 operators, 100 designers with 16 international bids, 8 design bids and involved the palace, the village, the castle of the Mandria, the gardens and the park. The allocated funds amounted to over 300 million euros (50 from the Ministry of Culture, 80 from the Piedmont Region, 170 from the European Union), have allowed the restoration of the entire complex, for a total area of 240,000 m2 and 800,000 m2 of gardens, 1000 frescoes, 9.5000 m2 stuccoes, with a cost of less than €900/m2.[10][11]

In 1997 it was added to the UNESCO Heritage List as part of the Residences of the Royal House of Savoy, together with other landmarks such as the Royal Palace of Turin and the Palazzina di caccia of Stupinigi.[11]

The complex was open for tourism from 13 October 2007, and has since become a major tourist destination and space for exhibitions and events. It received 1,048,857 visitors in 2017, making it the sixth most visited museum in Italy.[2] In 2019 it was chosen as Italy's most beautiful parks.[12] The palace's restaurant was awarded a Michelin star.[13]

In recent years, it has served as a filming location for several movies, including The King's Man and Miss Marx.[14] The palace hosted the "Turquoise Carpet" and Opening Ceremony events for the Eurovision Song Contest 2022.[15]

Architecture

The Palace

The palace is made up of two distinct wings: the original 17th century Palace of Diana, covered in white plaster, and the later 18th-century addition, with exposed brickwork. The entrance of the palace leads into the Cour d'honneur ("Honour Court"), which once housed a fountain with a deer.

Palace of Diana

The Palace of Diana is the core of the complex and the oldest section of the palace. It was built between 1658 and 1663 under the direction of Amedeo di Castellamonte. The main facade, covered with plaster and featuring cornucopias, shells and fruits, is connected on the right by section with the 18th-century wing. The facade facing the Honor Court presents a loggia flanked by an arched entryway on its right. Originally, there was a twin archway on the left of the loggia, but it was removed during Garove's reworking.

The Cour d'honneur leads into the Sala di Diana (Hall of Diana), situated in the Palace of Diana, which functions as the heart of the palace. It is a rectangular room, decorated with stuccoes and paintings centered on the theme of hunting. These include the frescoed vault representing Olympus (work of Jan Miel) which pictures Jupiter offering a gift to Diana, huge equestrian portraits of the dukes and the court (works by various painters in the ducal service), and hunting-themed canvases by Jan Miel, including the Hunt for the Deer, the Hare, the Bear, the Fox, the Boar, the Death of the Deer, the Going to the Woods, the Assembly, the Curea.[16]

18th century wing

The two pavilion date to the Michelangelo Garove period (1669–1713) and are covered with multicolor pentagonal tiles in ceramics, which are united by a large gallery, known as Grand Gallery (Galleria Grande). The centerpiece of the 18th-century wing is the Galleria Grande (Grand Gallery), which is stucco decorations, 44 arched windows, and black and white tiled floor.[16] The interiors originally housed a large collection of stuccos, statues, paintings (according to Amedeo di Castellamonte, up to 8,000) from some of the court artists of the times, such as Vittorio Amedeo Cignaroli, Pietro Domenico Olivero and Bernardino Quadri.

Gardens

The original gardens of the residence have now totally disappeared, since French troops turned them into training grounds. Earlier drawings show an Italian garden with three terraces connected by elaborate stairways and architectural features such as a clock tower in the first court, the fountain of Hercules, a theatre and parterres.

Recent works have recreated a park in modern style, exhibiting modern works by Giuseppe Penone, including a fake 12 m-high cedar housing the thermic discharges of the palace.

The palace with its gardens. The 17th-century wing on the right (in white plaster) while the 18th century wing is in the center (with a brick exterior).

The palace with its gardens. The 17th-century wing on the right (in white plaster) while the 18th century wing is in the center (with a brick exterior). The Juvarra stables

The Juvarra stables The palace seen from the gardens (17th century wing on the right, 18th century wing on the left)

The palace seen from the gardens (17th century wing on the right, 18th century wing on the left)

Juvarra Stables and Citroneria

The Juvarrian stables consist of a large atrium (room 57) overlooking the gardens, and a large vaulted room divided in two by a wall: the Scuderia Grande (Grand Stable, room 58) on the north side, and the Citroneria (orangery, room 59) on the side south. The Citroniera consists of a large vaulted gallery (148 meters long, 14 wide, and 16 high) whose ancient function was the winter storage of citrus fruits grown in the gardens. The side walls are decorated by niches that give the gallery dynamism, the south the walls feature large arches surmounted by oculi that overlook the gardens, while the north wall (which separates the room from the stables) has trompe l'oeil windows that mimics the arches of the south wall. The environment is currently used for temporary exhibitions. The large stable (148 m long, 12 wide and 15 high) contained about 200 horses at the time and sheltered the north side of the Citroniera in winter. Currently, the room exhibits carriages, uniforms, and the Venetian Bucintoro. The latter was commissioned in Venice by Vittorio Amedeo II between 1729 and 1731. Among the carriages on display there is the golden gala sedan, commissioned by Vittorio Emanuele II, the silver sedan of Queen Margherita and some carriages of Umberto I and Vittorio Emanuele III. In addition, Napoleon's carriage on temporarily exhibition.[17][18]

Church of Sant'Uberto

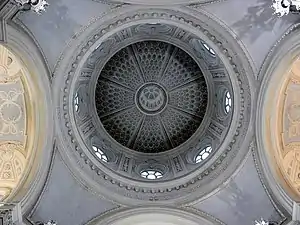

After the death of Garove (1713), Juvarra was commissioned by Vittorio Amedeo II to build a church dedicated to Saint Hubertus, patron of hunters. The grandiose baroque church was built between 1716 and 1729 and presents a Greek-cross plan with an octagonal core, and houses a large high altar inside, two side altars, and four side chapels located diagonally. Due to the church's position within the palace complex, it was impossible to build a dome. It was instead simulated with a trompe-l'œil painted on the vaulting by Giovanni Antonio Galliari. Juvarra decided to push facade back from in relation to the Grand Galley, in order to obtain a parvise in front of the church.[19][20]

Inside, the entablature is supported by tall lesenes topped with Corinthian capitals. The sculptural program, built between 1724 and 1729, is the work of Giovanni Baratta and his nephew Giovanni Antonio Cybei. It features tribunes on the upper level, that were used by the monarch and the royal court when attending mass.[21] the large high altar, decorated with flying angels supporting a ciborium in the shape of a small temple, and the four statues of the doctors of the church: St. Augustine, St. Ambrose, St. Athanasius and St. John Chrysostom around the central nave. The pictorial program, centred on the figure of the Virgin Mary and associated saints, is presented on the paintings placed on the side altars and in the chapels, works by Francesco Trevisani, Sebastiano Ricci and Sebastiano Conca. The upper level of the church houses tribunes The baptismal font is located in the chapel to the left of the entrance. The connections of the church with the Royal Palace were completed under Carlo Emanuele III by Benedetto Alfieri, who also designed the monumental staircase that gives access to the upper tribune and the tunnel connecting the chapel with the Citroniera. After the period of abandonment of the palace, the chapel underwent a minor renovation in 1961 on the occasion of the 1961 Italian Expo, and then a complete renovation with the rest of the palace in 1999. Its opening to the public was celebrated on 3 September 2006 with a concert.[19][20]

The exterior and main façade of the church

The exterior and main façade of the church The Trompe-l'œil mimicking the dome

The Trompe-l'œil mimicking the dome Interior of the chapel

Interior of the chapel The central space

The central space

The main altar

The main altar A side altar

A side altar

Gallery

The Court's departure for the hunt from the Venaria Reale by Melchior Hamers, 1668

The Court's departure for the hunt from the Venaria Reale by Melchior Hamers, 1668 The Belvedere and the Garove Pavilion

The Belvedere and the Garove Pavilion Galleria Grande (erroneously known as "Diana's Gallery")

Galleria Grande (erroneously known as "Diana's Gallery") View of the town and the palace in the late 17th century)

View of the town and the palace in the late 17th century)

See also

- List of Baroque residences

- Lux (album) – a 2012 album by Brian Eno which was initially a soundtrack for the Grand Gallery

Sources

References

- ↑ "History in brief". 8 November 2017.

- 1 2 "Musei, monumenti e aree archeologiche statali" [State museums, monuments and archaeological areas] (PDF). ilsole24ore.it (in Italian). 5 January 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Vinardi, Maria Grazia (2022). "La Venaria Reale". In Ricuperati, Giuseppe (ed.). Storia di Torino (in Italian). Einaudi. p. 463-481. ISBN 9788806162115.

- ↑ Cornaglia, Paolo. "La Reggia di Diana" (PDF). Reggia di Venaria. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ↑ http://www.21-style.com, MuseoTorino,Comune di Torino,Direzione Musei,Assessorato alla Cultura e al 150° dell’Unità d’Italia, 21Style. "Venaria Reale, Reggia di Diana - MuseoTorino". www.museotorino.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2023-04-11.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ↑ "History in brief". La Venaria Reale. 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Martinelli, Nicole (16 December 2007). "A Pleasure Palace Rises Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ Conticello, Anna (1992). Condotte nei restauri (in Italian). L'ERMA di BRETSCHNEIDER. ISBN 978-88-7062-779-4.

- ↑ "Restauro". La Venaria Reale (in Italian). 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- ↑ "Restauro". La Venaria Reale (in Italian). 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- 1 2 Martinelli, Nicole (16 December 2007). "A Pleasure Palace Rises Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ "I giardini della reggia di Venaria: ecco il parco più bello d'Italia". la Repubblica (in Italian). 2019-10-03. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "Dolce Stil Novo alla Reggia – Venaria Reale - a MICHELIN Guide Restaurant". MICHELIN Guide. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "Know About The King's Man Filming Locations | Readsme". 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "Eurovision 2022: All the news and looks from the Turin Turquoise Carpet". Eurovision.tv. 2022-05-08. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- 1 2 "Storia della Reggia di Venaria Reale: tutto ciò che c'è da sapere". Mole24 (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "Bucintoro reale dei Savoia". La Venaria Reale (in Italian). 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "The Juvarra Stables". La Venaria Reale. 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- 1 2 "The Church of St. Hubert". La Venaria Reale. 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- 1 2 "Chiesa di Sant'Uberto". Museo Torino (in Italian). Museo Torino, Comune di Torino, Direzione Musei, Assessorato alla Cultura e al 150° dell'Unità d'Italia, 21Style. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ "La Venaria Reale - Recensioni - Arte - Repubblica.it". www.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

External links

- Official website (in English)

- A.V.T.A. – Royal Palace of Venaria (en)

- Martinelli, Nicole (16 December 2007). "A Pleasure Palace Rises Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- Virtual tour of the Palace of Venaria provided by Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Reggia (Venaria Reale) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Reggia (Venaria Reale) at Wikimedia Commons