In geometry, an orthocentric system is a set of four points on a plane, one of which is the orthocenter of the triangle formed by the other three. Equivalently, the lines passing through disjoint pairs among the points are perpendicular, and the four circles passing through any three of the four points have the same radius.[1]

If four points form an orthocentric system, then each of the four points is the orthocenter of the other three. These four possible triangles will all have the same nine-point circle. Consequently these four possible triangles must all have circumcircles with the same circumradius.

The common nine-point circle

The center of this common nine-point circle lies at the centroid of the four orthocentric points. The radius of the common nine-point circle is the distance from the nine-point center to the midpoint of any of the six connectors that join any pair of orthocentric points through which the common nine-point circle passes. The nine-point circle also passes through the three orthogonal intersections at the feet of the altitudes of the four possible triangles.

This common nine-point center lies at the midpoint of the connector that joins any orthocentric point to the circumcenter of the triangle formed from the other three orthocentric points.

The common nine-point circle is tangent to all 16 incircles and excircles of the four triangles whose vertices form the orthocentric system.[2]

The common orthic triangle, its incenter, and its excenters

If the six connectors that join any pair of orthocentric points are extended to six lines that intersect each other, they generate seven intersection points. Four of these points are the original orthocentric points and the additional three points are the orthogonal intersections at the feet of the altitudes. The joining of these three orthogonal points into a triangle generates an orthic triangle that is common to all the four possible triangles formed from the four orthocentric points taken three at a time.

The incenter of this common orthic triangle must be one of the original four orthocentric points. Furthermore, the three remaining points become the excenters of this common orthic triangle. The orthocentric point that becomes the incenter of the orthic triangle is that orthocentric point closest to the common nine-point center. This relationship between the orthic triangle and the original four orthocentric points leads directly to the fact that the incenter and excenters of a reference triangle form an orthocentric system.[3]

It is normal to distinguish one of the orthocentric points from the others, specifically the one that is the incenter of the orthic triangle; this one is denoted H as the orthocenter of the outer three orthocentric points that are chosen as a reference triangle △ABC. In this normalized configuration, the point H will always lie within the triangle △ABC, and all the angles of triangle △ABC will be acute. The four possible triangles referred above are then triangles △ABC, △ABH, △ACH, △BCH. The six connectors referred above are AB, AC, BC, AH, BH, CH. The seven intersections referred above are A, B, C, H (the original orthocentric points), and HA, HB, HC (the feet of the altitudes of triangle △ABC and the vertices of the orthic triangle).

The orthocentric system and its orthic axes

The orthic axis associated with a normalized orthocentric system A, B, C, H, where △ABC is the reference triangle, is a line that passes through three intersection points formed when each side of the orthic triangle meets each side of the reference triangle. Now consider the three other possible triangles, △ABH, △ACH, △BCH. They each have their own orthic axis.

Euler lines and homothetic orthocentric systems

Let vectors a, b, c, h determine the position of each of the four orthocentric points and let n = (a + b + c + h) / 4 be the position vector of N, the common nine-point center. Join each of the four orthocentric points to their common nine-point center and extend them into four lines. These four lines now represent the Euler lines of the four possible triangles where the extended line HN is the Euler line of triangle △ABC and the extended line AN is the Euler line of triangle △BCH etc. If a point P is chosen on the Euler line HN of the reference triangle △ABC with a position vector p such that p = n + α(h – n) where α is a pure constant independent of the positioning of the four orthocentric points and three more points PA, PB, PC such that pa = n + α(a – n) etc., then P, PA, PB, PC form an orthocentric system. This generated orthocentric system is always homothetic to the original system of four points with the common nine-point center as the homothetic center and α the ratio of similitude.

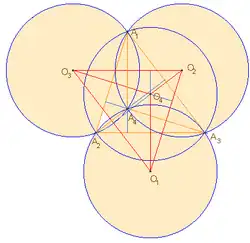

When P is chosen as the centroid G, then α = –⅓. When P is chosen as the circumcenter O, then α = –1 and the generated orthocentric system is congruent to the original system as well as being a reflection of it about the nine-point center. In this configuration PA, PB, PC form a Johnson triangle of the original reference triangle △ABC. Consequently the circumcircles of the four triangles △ABC, △ABH, △ACH, △BCH are all equal and form a set of Johnson circles as shown in the diagram adjacent.

Further properties

The four Euler lines of an orthocentric system are orthogonal to the four orthic axes of an orthocentric system.

The six connectors that join any pair of the original four orthocentric points will produce pairs of connectors that are orthogonal to each other such that they satisfy the distance equations

where R is the common circumradius of the four possible triangles. These equations together with the law of sines result in the identity

Feuerbach's theorem states that the nine-point circle is tangent to the incircle and the three excircles of a reference triangle. Because the nine-point circle is common to all four possible triangles in an orthocentric system it is tangent to 16 circles comprising the incircles and excircles of the four possible triangles.

Any conic that passes through the four orthocentric points can only be a rectangular hyperbola. This is a result of Feuerbach's conic theorem that states that for all circumconics of a reference triangle that also passes through its orthocenter, the locus of the center of such circumconics forms the nine-point circle and that the circumconics can only be rectangular hyperbolas. The locus of the perspectors of this family of rectangular hyperbolas will always lie on the four orthic axes. So if a rectangular hyperbola is drawn through four orthocentric points it will have one fixed center on the common nine-point circle but it will have four perspectors one on each of the orthic axes of the four possible triangles. The one point on the nine-point circle that is the center of this rectangular hyperbola will have four different definitions dependent on which of the four possible triangles is used as the reference triangle.

The well documented rectangular hyperbolas that pass through four orthocentric points are the Feuerbach, Jeřábek and Kiepert circumhyperbolas of the reference triangle △ABC in a normalized system with H as the orthocenter.

The four possible triangles have a set of four inconics known as the orthic inconics that share certain properties. The contacts of these inconics with the four possible triangles occur at the vertices of their common orthic triangle. In a normalized orthocentric system the orthic inconic that is tangent to the sides of the triangle △ABC is an inellipse and the orthic inconics of the other three possible triangles are hyperbolas. These four orthic inconics also share the same Brianchon point H, the orthocentric point closest to the common nine-point center. The centers of these orthic inconics are the symmedian points K of the four possible triangles.

There are many documented cubics that pass through a reference triangle and its orthocenter. The circumcubic known as the orthocubic - K006 is interesting in that it passes through three orthocentric systems as well as the three vertices of the orthic triangle (but not the orthocenter of the orthic triangle). The three orthocentric systems are the incenter and excenters, the reference triangle and its orthocenter and finally the orthocenter of the reference triangle together with the three other intersection points that this cubic has with the circumcircle of the reference triangle.

Any two polar circles of two triangles in an orthocentric system are orthogonal.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Kocik, Jerzy; Solecki, Andrzej (2009). "Disentangling a triangle" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly. 116 (3): 228–237.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Orthocentric System." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ↑ Johnson 1929, p. 182.

- ↑ Johnson 1929, p. 177.

References

- Johnson, Roger A. (1929). Modern Geometry: An Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of the Triangle and the Circle. Houghton Mifflin. Republished as Advanced Euclidean Geometry. Dover. 1960; 2007. See especially Chapter IX. Three Notable Points.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Orthocenter". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Feuerbach's Theorem". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Feuerbach's Conic Theorem". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Feuerbach Hyperbola". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Jerabek Hyperbola". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Kiepert Hyperbola". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Orthic Inconic". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Orthic Axis". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Perspector". MathWorld.

- Bernard Gibert Circumcubic K006

- Clark Kimberling, "Encyclopedia of triangle centers". (Lists some 5000 interesting points associated with any triangle.)