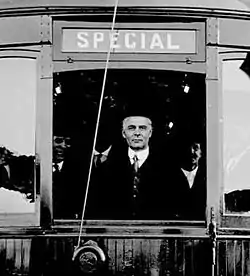

Ole Hanson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Seattle | |

| In office March 18, 1918 – August 28, 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Hiram C. Gill |

| Succeeded by | C. B. Fitzgerald |

| Member of the Washington House of Representatives from the 43rd district | |

| In office 1909–1911 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 6, 1874 Union Grove, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | July 6, 1940 (aged 66) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (1918–) |

| Other political affiliations | Progressive "Bull Moose" (1912) |

| Children | 10 |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Known for | Founder of San Clemente, California |

Ole Hanson (January 6, 1874 – July 6, 1940) was an American politician who served as mayor of Seattle, Washington, from 1918 to 1919. Hanson became a national figure promoting law and order when he took a hardline position during the 1919 Seattle General Strike. He then resigned as mayor, wrote a book, and toured the lecture circuit, earning tens of thousands of dollars in honoraria lecturing to conservative civic groups about his experiences and views, promoting opposition to labor unions and Bolshevism. Hanson later left Washington and founded the city of San Clemente, California, in 1925.[1]

Biography

Early years

Ole Hanson was born in a log cabin in Union Grove in Racine County, Wisconsin, the son of Thorsten Hanson and Goro Tostofson Hanson.[2] He was the fifth of six children raised by the Norwegian immigrant couple.[3]

As a teenager, the precocious Hanson worked as a tailor during the day and studied law at night.[3] He passed the Wisconsin bar in 1893, despite being two years too young to practice law.[3] In the end, Hanson never did work in the legal profession, instead going into the grocery business before moving west and going into real estate.[4]

He worked as a real estate developer and co-founded Lake Forest Park, Washington, in 1912 as a rural planned community for professionals in the Seattle area.[5]

Political career

Entering political life, he served in the Washington House of Representatives during 1908 and 1909.[2] In 1912 he supported Theodore Roosevelt for President of the United States.[1] In 1914, Hanson himself ran for the United States Senate as the candidate of the so-called Bull Moose Party.[2] Hanson garnered nearly a quarter of the vote in the five-way race, won by Republican incumbent Wesley Livsey Jones with a 37% plurality.

In March 1918, Hanson was elected the thirty-third mayor of Seattle. Both he and his opponent, James Bradford, were progressive Republicans, but Hanson was considered more pro-labor. He ran on a platform of patriotism, eight hour workday for female workers, a minimum wage, initiative and referendum, and others. Predicted to win a strong majority, Hanson won by a slimmer margin of 32,286 to 27,677 for Bradford, or about seven points. Hanson supported the recall of socialist Anna Louise Strong from her school board seat.[6]

In February 1919, tens of thousands of workers went on strike in what would become the Seattle General Strike. In 1916 and 1918, there was nearly a general strike, but negotiations had successfully defused the situation, while in 1919 they failed. Caused by the lowering of wages of shipyard workers, almost two dozen unions joined the strike.[7] Right before and after his election, relations had soured between Hanson and the unions, and he was intensely critical of the Industrial Workers of the World on the campaign. Hanson deputized three thousand soldiers from Fort Lewis, and threatened to impose martial law despite lacking the authority to do so. Lacking cohesion and clear demands, the general strike began to dissipate as workers went back to work. Before a full week had passed, the strike was ended. Hanson received praise and national attention for his steadfastness against the unions.[8]

In April 1919, anarchists made him one of the targets of booby-trap bombs mailed to approximately 30 prominent American officials. Hanson survived the assassination attempt,[1] and responded by calling for a nationwide campaign of hangings and life imprisonment for members of the I.W.W. and other radicals.[9] He resigned as Mayor on August 28, 1919, saying: "I am tired out and am going fishing."[4][10]

Following his resignation, Hanson set to work writing a book on what he perceived to be the radical menace to America, published in January 1920 in the immediate aftermath of the so-called "Palmer Raids" as Americanism versus Bolshevism. In this tome, Hanson declared:[11]

I am tired of reading rhetorical, finely spun, hypocritical, far-fetched excuses for bolshevism, communism, syndicalism, IWWism! Nauseated by the sickly sentimentality of those who would conciliate, pander, and encourage all who would destroy our Government, I have tried to learn the truth and tell it in United States English of one or two syllables.... With syndicalism — and its youngest child, bolshevism — thrive murder, rape, pillage, arson, free love, poverty, want, starvation, filth, slavery, autocracy, suppression, sorrow and Hell on earth. It is a class government of the unable, the unfit, the untrained; of the scum, of the dregs, of the cruel, and of the failures. Freedom disappears, liberty emigrates, universal suffrage is abolished, progress ceases,...and a militant minority, great only in their self-conceit, reincarnate under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat a greater tyranny than ever existed under czar, emperor, or potentate.

In Hanson's view, the fact that the 1919 Seattle general strike was peaceful belied its revolutionary nature and intent. He wrote:[12]

The so-called sympathetic Seattle strike was an attempted revolution. That there was no violence does not alter the fact... The intent, openly and covertly announced, was for the overthrow of the industrial system; here first, then everywhere... True, there were no flashing guns, no bombs, no killings. Revolution, I repeat, doesn't need violence. The general strike, as practised in Seattle, is of itself the weapon of revolution, all the more dangerous because quiet. To succeed, it must suspend everything; stop the entire life stream of a community... That is to say, it puts the government out of operation. And that is all there is to revolt — no matter how achieved.

Hanson toured the country giving lectures about the dangers of "domestic bolshevism." He earned $38,000 in 7 months, 5 times his annual salary as mayor.[13]

Founding San Clemente

In 1925, Hanson put some of his wealth to work by purchasing a 2,000-acre (8.1 km2) tract at the southern tip of Orange County, California. Hanson believed that the area's pleasant climate, beautiful beaches and fertile soil would serve as a haven to Californians who were tired of urban life. He named the city San Clemente after neighboring San Clemente Island, southernmost of California's Channel Islands.

Hanson envisioned his new project as a Spanish-style coastal resort town. He proclaimed, "I have a clean canvas and I am determined to paint a clean picture. Think of it — a canvas five miles long and one-half miles wide!"

In an unprecedented move, Hanson had a clause added to all deeds requiring that building plans be submitted to an architectural review board in an effort to ensure that future development would retain Spanish Colonial Revival style influence. Red tile roofs became a stylistic signature of the new community. Hanson succeeded in promoting his new venture and selling property to interested buyers. The area was officially incorporated as a city on February 27, 1928.

Over the years, Hanson built various public structures in San Clemente, including the Beach Club, the Community Center, the pier, and Max Berg Plaza Park, which were later donated to the city. He also had a Spanish Style home built overlooking the San Clemente Pier. This home was later named Casa Romantica.

Financially leveraged with mortgages on his various property ventures, Hanson lost all his remaining holdings during the Great Depression, including his beloved mansion in San Clemente.[3] Hanson eventually moved along to launch a new property development at Twentynine Palms in San Bernardino County, California.[3]

Death and legacy

Ole Hanson died of a heart attack on July 6, 1940, in Los Angeles, California.[3] He was 66 years old at the time of his death. Hanson was survived by his widow and ten children.[1]

The city of San Clemente bears numerous reminders of its founding father, including the Ole Hanson historic pool which overlooks the Pacific Ocean. His home in the center of the city overlooking the historic pier was restored and opened to the community as a cultural center.

Works

- Address to the American Legion on "Bolshevism" praises the Russian people for overthrowing the Czarist autocracy

- Americanism vs. Bolshevism Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1920.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "Ole Hanson, Once Mayor of Seattle, Broke General Strike, Which Involved 65,000, in 1919 After 5 Days. Dies in Los Angeles. Former Teacher, Lawyer. Candidate for Senate in 1912 on Bull Moose Ticket. Was California Realty Man". New York Times. Associated Press. July 8, 1940.

- 1 2 3 Lawrence Kestenbaum, "Ole Hanson," PoliticalGraveyard.com Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Don Kindred, The Legend of Ole Hanson (San Clemente Journal, SanClemente.com/) Archived March 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Ole Hanson Quits as Seattle Mayor (New York Times August 29, 1919)

- ↑ - https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/covenants/LakeForestPark.PDF 1910 LFP plats

- ↑ "Voters elect Ole Hanson mayor of Seattle on March 5, 1918". www.historylink.org. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Seattle shipyard strike begins on January 21, 1919. - HistoryLink.org". www.historylink.org. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Hanson, Ole Thorsteinsson (1874-1940)". www.historylink.org. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Hang or Imprison All Reds Declares Mayor Ole Hanson". The Morning Press. May 2, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved August 7, 2019 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ↑ "Mayor Ole Hanson Resigns". Lime Springs Herald. September 4, 1919. p. 7. Retrieved July 18, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Ole Hanson, Americanism versus Bolshevism. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1920; pp. vii-viii.

- ↑ Quoted in Jeremy Brecher, Strike!, 126

- ↑ Murray, Robert K. (1955). Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919-1920. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 9780816658336. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Further reading

- Jeremy Brecher, Strike! Revised edition. Boston: South End Press, 1997.

- Ann Hagedorn, Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007.

- Terje I. Leiren, "Ole and the Reds: The 'Americanism' of Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson," Norwegian-American Studies, Volume 30, pg. 75.

- Robert K. Murray, Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919-1920 Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955.

External links

- Cliffe, "Know Your Mayor: Ol' Ole Hanson," VintageSeattle.org, November 27, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- Trevor Williams, Ole Hanson's Fifteen Minutes, Seattle General Strike Project, Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies at the University of Washington, 1999.