| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H30N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 366.505 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

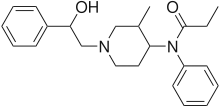

Ohmefentanyl (also known as β-hydroxy-3-methylfentanyl, OMF and RTI-4614-4)[1] is an extremely potent opioid analgesic drug which selectively binds to the µ-opioid receptor.[2][3]

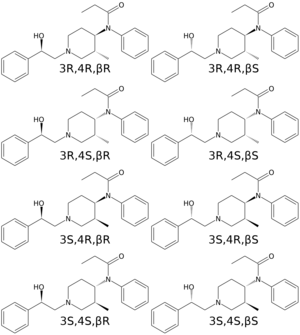

There are eight possible stereoisomers of ohmefentanyl. These stereoisomers are among the most potent μ-opioid receptor agonists known, comparable to super-potent opioids such as carfentanil and etorphine which are only legally used for tranquilizing large animals such as elephants in veterinary medicine. In mouse studies, the most active stereoisomer, 3R,4S,βS-ohmefentanyl, was 28 times more powerful as a painkiller than fentanyl, the chemical from which it is derived, and 6300 times more powerful than morphine.[4][5][6][7] Ohmefentanyl has three stereogenic centers and eight stereoisomers, which are named F9201–F9208. Researchers are studying the different pharmaceutical properties of these isomers.[8]

The 4″-fluoro analogue (i.e., substituted on the phenethyl ring) of the 3R,4S,βS isomer of ohmefentanyl is one of the most potent opioid agonists yet discovered, possessing an analgesic potency approximately 18,000 times that of morphine.[9] Other analogues with potency higher than that of ohmefentanyl itself include the 2′-fluoro derivative (i.e., substituted on the aniline phenyl ring), and derivatives where the N-propionyl group was replaced by N-methoxyacetyl or 2-furamide groups, or a carboethoxy group is added to the 4-position of the piperidine ring. The latter is listed as being up to 30,000 times more potent than morphine.[10]

Side effects of fentanyl analogues are similar to those of fentanyl itself, which include itching, nausea and potentially serious respiratory depression, which can be life-threatening. Illicitly used fentanyl analogues have killed hundreds of people throughout Europe and the former Soviet republics since the most recent resurgence in use began in Estonia in the early 2000s, and novel derivatives continue to appear.[11]

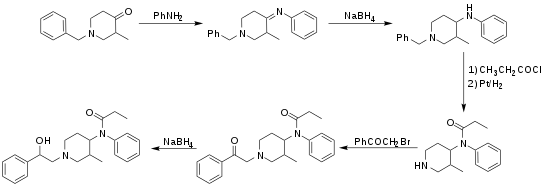

Synthesis

See also

References

- ↑ Rothman RB, Xu H, Seggel M, Jacobson AE, Rice KC, Brine GA, Carroll FI (April 1991). "RTI-4614-4: an analog of (+)-cis-3-methylfentanyl with a 27,000-fold binding selectivity for mu versus delta opioid binding sites". Life Sciences. 48 (23): PL111–PL116. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(91)90346-D. PMID 1646357.

- ↑ Brine GA, Stark PA, Liu Y, Carroll FI, Singh P, Xu H, Rothman RB (April 1995). "Enantiomers of diastereomeric cis-N-[1-(2-hydroxy-2-phenylethyl)- 3-methyl-4-piperidyl]-N-phenylpropanamides: synthesis, X-ray analysis, and biological activities". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 38 (9): 1547–1557. doi:10.1021/jm00009a015. PMID 7739013.

- ↑ Wang ZX, Zhu YC, Jin WQ, Chen XJ, Chen J, Ji RY, Chi ZQ (September 1995). "Stereoisomers of N-[1-hydroxy-(2-phenylethyl)-3-methyl-4-piperidyl]- N-phenylpropanamide: synthesis, stereochemistry, analgesic activity, and opioid receptor binding characteristics". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 38 (18): 3652–3659. doi:10.1021/jm00018a026. PMID 7658453.

- ↑ H. D. Banks, C. P. Ferguson (September 1988). "The Metabolites of Fentanyl and its Derivatives" (PDF). U.S. Army Chemical Research, Development and Engineering Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ↑ Jin WQ, Xu H, Zhu YC, Fang SN, Xia XL, Huang ZM, et al. (May 1981). "Studies on synthesis and relationship between analgesic activity and receptor affinity for 3-methyl fentanyl derivatives". Scientia Sinica. 24 (5): 710–720. PMID 6264594.

- ↑ Zhu YC, Wu RQ, Chou DP, Huang ZM (December 1983). "[Studies on potent analgesics. VII. Synthesis and analgesic activity of diastereoisomers of 1-beta-hydroxy-3-methylfentanyl (7302) and related compounds]". Yao Xue Xue Bao = Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 18 (12): 900–904. PMID 6679170.

- ↑ Guo GW, He Y, Jin WQ, Zou Y, Zhu YC, Chi ZQ (June 2000). "Comparison of physical dependence of ohmefentanyl stereoisomers in mice". Life Sciences. 67 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00617-2. PMID 10901279.

- ↑ Liu ZH, He Y, Jin WQ, Chen XJ, Shen QX, Chi ZQ (April 2004). "Effect of chronic treatment of ohmefentanyl stereoisomers on cyclic AMP formation in Sf9 insect cells expressing human mu-opioid receptors". Life Sciences. 74 (24): 3001–3008. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.027. PMID 15051423.

- ↑ Yong Z, Hao W, Weifang Y, Qiyuan D, Xinjian C, Wenqiao J, Youcheng Z (May 2003). "Synthesis and analgesic activity of stereoisomers of cis-fluoro-ohmefentanyl". Die Pharmazie. 58 (5): 300–302. PMID 12779044.

- ↑ Brine GA, Carroll FI, Richardson-Leibert TM, Xu H, Rothman RB (August 1997). "Ohmefentanyl and its stereoisomers: Chemistry and pharmacology". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 4 (4): 247–270. doi:10.2174/0929867304666220313115017. ISSN 0929-8673.

- ↑ Mounteney J, Giraudon I, Denissov G, Griffiths P (July 2015). "Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 26 (7): 626–631. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.003. PMID 25976511.

External links

- Ohmefentanyl at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)