Blessed Odoric of Pordenone | |

|---|---|

The departure of Odoric | |

| Born | c. 1280 Pordenone, Patriarchate of Aquileia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | January 14, 1331 (aged 44–45) Udine, Patriarchate of Aquileia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholicism (Franciscan Order) |

| Beatified | 2 July 1755, Saint Peter's Basilica, Papal States by Pope Benedict XIV |

| Major shrine | Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Udine, Italy |

| Feast | January 14 |

Odoric of Pordenone[lower-alpha 1] (c. 1280–14 January 1331), was a Franciscan friar and missionary explorer from Friuli in northeast Italy. He journeyed through India, Sumatra, Java, and China, where he spent three years in the imperial capital of Khanbaliq (now Beijing). After more than ten years of travel, he returned home and dictated a narrative of his experiences and observations called the Relatio, highlighting various cultural, religious, and social peculiarities he encountered in Asia.

His manuscript was copied multiple times and distributed widely across Europe, both in the original Latin and several vernacular translations including Italian, French, and German. The Relatio was an important contribution to Europe's growing awareness of the Far East.

Odoric's account was a primary source for the account of Mandeville's Travels. Many of the incredible reports about Asia in Mandeville have proven to be versions of Odoric's eyewitness descriptions.[1]

After his death, Odoric became an object of popular devotion and was beatified in 1755.

Early life

Little is known about the life of Odoric and many details are confused by the mythology that evolved after his death.[2] He was born at Villanova, a hamlet now belonging to the town of Pordenone in Friuli. One tradition says that he was the son of a soldier fighting for Ottokar II of Bohemia, who seized control of Pordenone in the early 1270s. For this reason he has sometimes been called "the Bohemian". Another tradition says that Odoric was the son of a prominent local family but recent historians tend to discount this version.[3][4] Estimates of his birth year have ranged from 1265 to 1285 but a forensic examination of his partially mummified body in 2002 showed he was about 50 when he died in 1331, indicating that he was born around 1280.[4]

His 14th-century ecclesiastical biographers said that he took the vows of the Franciscan order at a very young age. The earliest record of his association with the order is a legal document he signed as a member of the Order of Friars Minor in 1296. He signed other documents in 1316, 1317 and 1318, indicating his presence in Friuli during this period. The nature of these documents also suggests the prestige and the high-level social and institutional relationships he maintained.[4]

Odoric in context

Odoric's journey had been preceded by a period of Papal diplomatic missions that began nearly a century earlier when Mongols had entered Europe in the Mongol invasion of Europe. Between 1237 and 1238 they pillaged most of Russia, and by 1241 they had devastated Poland and Hungary. Then they suddenly retreated. At the First Council of Lyon, Pope Innocent IV organized the first missions to the Great Khan Tartary in 1245, entrusted to the Franciscans, as were subsequent Papal missions over the next century.[5]

By 1260, the fear of another Mongol invasion had subsided and during the next 100 years there were numerous contacts between Europe and China focused on trade opportunities and religious conversion. Travel was facilitated by a united and peaceful Mongolian empire under the Yuan dynasty. Mongolian polytheism was tolerant of the Christian religion and welcomed foreign divinities into its pantheon. Niccolò, Matteo, and Marco Polo made two voyages in 1260 and 1271, and in 1294 the missionary John of Monte Corvino made a similar journey for Pope Nicholas IV. As a result of these and other travelers, information about the Far East started to circulate in Europe.[5][6]

There is no evidence that Odoric had any diplomatic responsibilities when he undertook his journey. He was motivated to evangelize and perhaps satisfy his own curiosity. In the opening chapter of his chronicle, he states "according to my wish, I crossed the sea and visited the countries of the unbelievers in order to win some harvest of souls."[7]

Journey to China

Sometime after 1318, Odoric left Venice to begin his multi-year journey across Asia.[4] In the introduction to his travel journal, Odoric says that he went as a missionary and never alludes to any other capacity such as an ambassador or emissary. No records have been found to indicate whether he was sent by some ecclesiastical authority or simply received permission to undertake a journey of his own choosing.[8][9]

There is little chronological information regarding the exact sequence and duration of the stops on his travel. His narrative and other evidence only tells us that he was in western India soon after 1321 (pretty certainly in 1322) and that he spent three years in China between the opening of 1323 and the close of 1328.[10] Along the way he provided brief descriptive notes for each of the places he visited, highlighting various cultural, religious, and social peculiarities.[4]

During at least a part of his journey, the companion of Odoric was Friar James of Ireland, who assisted at Odoric's funeral and subsequently received a payment of two marks from the city of Udine, recorded with the Latin notation, Socio beati Fratris Odorici, amore Dei et Odorici ('companion of the Blessed Brother Odoric, for the love of God and Odoric').[11]

From Venice he first went to Constantinople and then crossed the Black Sea to Trebizond. From Trebizond he traveled southeast along the caravan route to Erzerum, Tabriz, and Soltania. It is likely that he spent time at the Franciscan monasteries established in these cities. From Soltania his travels become somewhat confused. He seems to have wandered through Persia and Mesopotamia, visiting Kashan, Yazd, Persepolis, and Baghdad. From Baghdad he traveled along the Persian Gulf, and at Hormuz embarked for India.[12][13]

Odoric landed on the Indian coast at Tana where Thomas of Tolentino and his three Franciscan companions had recently been martyred for "blaspheming" Muhammad before the local magistrate or qadi. Their remains had been interred by Jordan of Severac, a Dominican missionary. Odoric relates that he recovered these relics and carried them with him on his further travels. From Tana, he travelled down the Malabar coast, stopping at Kodungallur and Quilon. From there, he proceeded around the southern tip of India and up along the southwest coast, where he visited the shrine of Thomas the Apostle, which tradition places near Chennai.[14][15]

From India, Odoric sailed in a junk to northern Sumatra, Java, and Borneo where he became the first European to make a recorded visit to the island.[2] At this point, his journey becomes somewhat confusing and it is not clear whether it is recorded in the correct chronological order. After visiting Champa, an ancient kingdom in Vietnam, Odoric says that he travelled to the islands of Nicobar and then on to Ceylon. After Ceylon, Odoric writes about 'Dondin', an island associated with the Andaman Islands by some historians while others believe it to be entirely fictional.[15][16]

Next he travelled to Guangzhou (which he knew as "Chin-Kalan" or "Mahachin"). From Guangzhou, he travelled overland to the great port of "Zayton" (possibly Quanzhou ) where there were two houses of his order. In one of these, he deposited the remains of the martyrs of Thane. A letter from the bishop, Andrea da Perugia, dated 1326, confirms their reception.

From Fuzhou Odoric struck across the mountains into Zhejiang and visited Hangzhou ("Cansay"). It was at the time one of the great cities of the world and Odoric —like Marco Polo, Marignolli, and Ibn Batuta—gives details of its splendors. He mentions Hangzhou as "greater city than any other in the world, being 100 miles around, with everywhere within inhabited; often a house has 10 or 12 families. The city has twelve gates and at each gate at about eight miles are cities larger than Venice or Padua".[17] Passing northward by Nanjing and crossing the Yangzi, Odoric embarked on the Grand Canal and travelled to the imperial city of the Great Khan (probably Yesün Temür Khan) at Khanbaliq (within present-day Beijing). He remained there for three years, probably from 1324 to 1327. He was attached, no doubt, to one of the churches founded by the Franciscan Archbishop John of Monte Corvino, at this time in extreme old age.[18] He also visited Yangzhou where Marco Polo had served as governor for three years.[19]

After three years in Khanbaliq, Odoric elected to travel back to Europe, possibly in response to the emperor's request for more missionaries.[20] His return journey is less clearly described. Traveling overland across Asia, he passed through what he called the kingdom of Prester John (possibly Mongolia), and then 'Kansan' (possibly Shaanxi). Some commentators have suggested that he may have been the first European to have reached Tibet,[18] but a number of modern scholars have contested this interpretation.[2] Beyond here, the friar likely proceeded through Kashmir, Afghanistan, Persia, Armenia and Trebizond, where may have caught a ship home to Venice.[20]

Return to Friuli

Odoric reached home sometime around the end of 1329 or the beginning of 1330. After a journey of more than ten years, he had travelled approximately 50,000 kilometers.[20] Shortly after his return Odoric was at his Order's house attached to the Friary of St. Anthony at Padua, and it was there in May 1330 that he related the story of his travels, which was taken down in simple Latin by Friar William of Solagna.[10]

From Padua he is thought to have proceeded to Pisa in order to take ship for the Papal Court at Avignon, where he wanted to report on the affairs of the church in the far East, and request recruits for the missions in Cathay. However, he fell ill in Pisa and returned home to Friuli where he died on January 14, 1331.[21]

The friars of the convent were about to bury him the same day privately, but when this became known in the city, Conrad Bernardiggi, the chief magistrate of Udine, who had a great regard for Odoric, intervened and appointed a solemn funeral for the next day. Rumours of his travels and the posthumous miracles attributed to Odoric spread rapidly through the population. The ceremony had to be deferred more than once, and at last took place in presence of the patriarch of Aquileia and many local dignitaries.[22]

As public veneration for Odoric grew, the patriarch ordered the body of the friar to be moved into a stone tomb, commissioned and paid for by the community of Udine and sculpted by a Venetian artist, Filippo de Sanctis. Odoric was placed in the church of San Francesco and the chapel dedicated to him was frescoed in the fifteenth century with episodes of his journey and his miracles. The tomb was removed due to the Venetian suppressions (1769) and after some wanderings it was placed in the church of San Maria del Carmine, where it is still to be found.[4]

Contemporary fame of his journeys

Popular acclamation made Oderic an object of devotion, the municipality erected a noble shrine for his body, and his fame as saint and traveller had spread far and wide before the middle of the century, but it was not until four centuries later (1755) that the papal authority formally sanctioned his beatification. A bust of Odoric was set up at Pordenone in 1881.[10]

There are a few passages in the book that stamp Odoric as a genuine and original traveller. He is the first European, after Marco Polo, who distinctly mentions the name of Sumatra. The cannibalism and community of wives which he attributes to certain people of that island do certainly belong to it, or to islands closely adjoining.[23] His description of sago in the archipelago is not free from errors, but they are the errors of an eye-witness.[10]

Regarding China, his mention of Guangzhou by the name of Censcolam or Censcalam (Chin-Kalan), and his descriptions of the custom of fishing with tame cormorants, of the habit of letting the fingernails grow extravagantly, and of the compression of women's feet, are peculiar to him among the travellers of that age; Marco Polo omits them all.[10] Odoric was one who not only visited many countries, but wrote about them so that he could share his knowledge with others.

Beatification

Moved by the many miracles that were wrought at the tomb of Odoric, Pope Benedict XIV, in the year 1755, approved the veneration which had been paid to Blessed Odoric. In the year 1881 the city of Pordenone erected a magnificent memorial to its distinguished son.

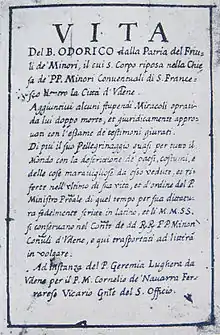

Manuscripts and published editions

The original manuscript of Odoric's narrative has been lost, but researchers have traced at least 117 copies, seventy-nine of them in Latin, twenty-three in Italian, eight in French, five in German, one in Castilian, and one in Welsh.[24] Most of the copies do not have a name so, by convention, scholars use the title Relatio.[25]

The work was read widely in Europe and manuscript copies can be found in libraries across the continent. The oldest surviving text is preserved in Assisi and three more copies nearly as old can be found in the Vatican library.[26][27]

The events narrated by Odoric after his return to Italy may have been transcribed several times. The most widespread version was made by William of Solagna who states in an introduction that he took down the dictation of Odoric while they were in Bologna in May 1330. Other compilations of the narrative were prepared in Latin or Italian and some of them were very dissimilar.[26]

Another contemporary version was made by Heinrich of Glatz (Silesia) who said he copied the text from a version he accessed in the papal library at Avignon (likely in 1331).[27] Each subsequent compiler or copyist modified the text as they saw fit. Some simply attempted to improve on the original Latin grammar while others added details or entirely new sections. In one German manuscript, for example, comparisons that Odoric frequently made between Chinese cities and Italian ones were replaced by comparisons with German cities. In France, comparisons were made to French cities and rivers. In other versions stories of miracles attributed to Odoric after his death were added in an effort to bolster the case for his beatification.[26]

A comprehensive study of all versions and their histories has not yet been done.[26]

The narrative was first printed at Pesaro in 1513, in what Apostolo Zeno (1668–1750) calls lingua inculta e rozza.[10]

Giovanni Battista Ramusio first includes Odoric's narrative in the second volume of the second edition (1574) (Italian version), in which are given two versions, differing curiously from one another, but without any prefatory matter or explanation. Another (Latin) version is given in the Acta Sanctorum (Bollandist) under 14 January. The curious discussion before the papal court respecting the beatification of Odoric forms a kind of blue-book issued ex typographia rev. camerae apostolicae (Rome, 1755). Friedrich Kunstmann of Munich devoted one of his papers to Odoric's narrative (Histor.-polit. Blätter von Phillips und Görres, vol. xxxvii. pp. 507–537).[10]

Some editions of Odoric are:

- Giuseppe Venni, Elogio storico alle gesta del Beato Odorico (Venice, 1761)

- Henry Yule in Cathay and the Way Thither, vol. i. pp. 1–162, vol. ii. appendix, pp. 1–42 (London, 1866), Hakluyt Society

- Henri Cordier, Les Voyages ... du frère Odoric ... (Paris, 1891) (edition of Old French version of c. 1350). Available at the Internet Archive

- Teofilo Domenichelli, Sopra la vita e i viaggi del Beato Odorico da Pordenone dell'ordine de'minori (Prato, 1881) (includes a Latin and an Italian text) (available at the Internet Archive)

- text embedded in the Storia universale delle Missione Francescane, by Marcellino da Civezza, iii. 739-781

- text embedded in Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations (1599), ii. 39-67.

- John of Viktring (Johannes Victoriensis) in Fontes rerum Germanicarum, ed. JF Böhmer

- Luke Wadding, Annales Minorum, A.D. 1331, vol. vii. pp. 123–126

- Bartholomew Rinonico, Opus conformitatum ... B. Francisci ..., bk. i. par. ii. conf. 8 (fol. 124 of Milan, edition of 1513)

- John of Winterthur in Eccard, Corpus historicum medii aevi, vol. i. cols. 1894-1897, especially 1894

- C. R. Beazley, Dawn of Modern Geography, iii. 250-287, 548-549, 554, 565-566, 612-613.[10]

Legacy

Minor planet 4637 Odorico is named after him.[28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Also known as Odorico, Odoricus, or Odorico the Bohemian

References

Citations

- ↑ Higgins 1997, pp. 2, 9, 10.

- 1 2 3 Howgego 2003.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tilatti 2013.

- 1 2 Chiesa 2002, pp. 17–22.

- ↑ Marchisio 2016, p. 43.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ O'Doherty 2006, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yule & Beazley 1911.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, p. 15.

- ↑ Yule 1913, p. 10.

- ↑ Rachewiltz 1971, p. 179.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, p. 30.

- 1 2 O'Doherty 2006, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, p. 116.

- ↑ Gernet 1962, p. 31.

- 1 2 Hartig 1911.

- ↑ Chiesa 2002, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Bressan 1997, pp. 9.

- ↑ Yule 1913, p. 12.

- ↑ Yule 1913, p. 13.

- ↑ Sir Henry Yule, ed. (1866). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Issue 36. pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Marchisio 2016, p. 49.

- ↑ Marchisio 2016, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Chiesa 2002, pp. 50–53.

- 1 2 Bressan 1997, p. 10.

- ↑ Minor Planet Center (4637) 1989 CT

Bibliography

- Bressan, L. (1997). "Odoric of Pordenone (1265-1331). His vision of China and South-East Asia and his contribution to relations between Asia and Europe". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 70 (2 (273)): 1–23. ISSN 0126-7353.

- Cameron, Nigel (1970). Barbarians and mandarins: thirteen centuries of Western travelers in China. New York: Walker/Weatherhill. pp. 107–120. ISBN 0802724035.

- Chiesa, Paolo, ed. (2002). "Introduction". The Travels of Friar Odoric. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0802849636.

- Dāsa, Jagannātha Prasāda (1982). Puri paintings : the chitrakāra and his work. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press. ISBN 0-391-02577-5. OCLC 8668302.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily life in China, on the eve of the Mongol invasion, 1250-1276. Stanford, Calif., Stanford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8047-0720-6.

- Higgins, Iain MacLeod (1997). Writing East : The "Travels" of Sir John Mandeville. Philadelphia, Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3343-8.

- Howgego, Raymond John, ed. (2003). "Odoric of Pordenone". Encyclopedia of Exploration to 1800. Hordern House. ISBN 1875567364.

- Marchisio, Annalia (2016). "Many Versions, One Edition Odorico da Pordenone's Travel to China". The Journal of Medieval Latin. 26: 43–76. ISSN 0778-9750.

- Maspero, G., & Tips, W. E. J. (2002). The Champa Kingdom: The history of an extinct Vietnamese culture. Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Press.

- Mitter, Partha (1977). Much maligned monsters : history of European reactions to Indian art. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-817336-9. OCLC 3741251.

- Moule, A. C. (1920). "A Life of Odoric of Pordenone". T'oung Pao. 20 (3/4): 275–290. ISSN 0082-5433.

- O'Doherty, Marianne (2006). Eyewitness Accounts of 'the Indies' in the Later Medieval West: Reading, Reception, and Re-use (c. 1300-1500) (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Leeds.

- Rachewiltz, Igor de (1971). Papal Envoys to the Great Khans. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0770-1.

- Starza, O. M. (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri : its architecture, art, and cult. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09673-6. OCLC 26635087.

- Tilatti, Andrea (2013). "Odorico da Pordenone". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Trecanni Instituto.

- Yule, Henry (1913). Cathay and the Way Thither. Vol. 2. London: Hakluyt Society.

- "Habig ofm ed., Marion, "Blessed Odoric Matiussi of Pordenone", The Franciscan Book of Saints, Franciscan Herald Press, 1959". Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hartig, Otto (1911). "Odoric of Pordenone". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hartig, Otto (1911). "Odoric of Pordenone". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12.- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Yule, Henry; Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). "Odoric". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

Popular translations

- Odoric of Pordenone, translation by Sir Henry Yule, introduction by Paolo Chiesa, The Travels of Friar Odoric: 14th Century Journal of the Blessed Odoric of Pordenone, Eerdmans (December 15, 2001), hardcover, 174 pages, ISBN 0802849636 ISBN 978-0802849632. Scan at Archive.org.

Further reading

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic source materials for the study of Philippine history. New Day Publishers. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-971-10-0226-8.

External links

- Viaggio del beato odoricl da vdine (Odoric travels) (1583) translated to Italian by Giovanni Battista Ramusio.