Newcomb Pottery, also called Newcomb College Pottery, was a brand of American Arts & Crafts pottery produced from 1895 to 1940.[1] The company grew out of the pottery program at H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, the women's college now associated with Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana. The Pottery was a contemporary of Rookwood Pottery, the Saturday Evening Girls, North Dakota pottery, Teco and Grueby.

The program

Newcomb College had been founded expressly to instruct young Southern women in liberal arts.[2] The art school opened in 1886 and production of art pottery on a for-profit basis began in 1895 under the supervision of art professors William Woodward, Ellsworth Woodward, and Mary Given Sheerer.[3][4][5]

Potters

.jpg.webp)

Among the first persons to be hired by the Woodwards to assist with the new pottery program were the potters. Unlike the artists who created and carved the designs for the Pottery, the potters were all men, as it was believed that a "male potter would be needed to work the clay, throw the pots, fire the kiln and handle the glazing."[6] The first potter hired was Jules Garby in 1895. He was followed by one of Newcomb Pottery's most recognized potters, Joseph Meyer, in 1896. Notably, George Ohr was hired as a potter at approximately the same time as Joseph Meyer, but Ohr left Newcomb to work on his own sometime in 1897.[6] Meyer's cipher is found on more pieces of Newcomb College Pottery than any other person.[6] Meyer won awards for his work at Newcomb at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo and the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition.[6] Meyer stayed with the Pottery until his retirement in 1927. He was replaced by Jonathan Hunt in 1927 and later Kenneth Smith in 1929. After Hunt left the Pottery in 1933, he was replaced by Francis Ford. Both Smith and Ford stayed with the Newcomb Pottery program through its termination in 1940.[6]

Craftsmen

When the Pottery was first established, any woman who studied art at Newcomb College was allowed to sell wares that she had decorated, provided it was judged to be adequate for sale by the faculty at the school.[6] Over the years, the Pottery employed dozens of women.

Some early Newcomb College artists included:[6]

- Sadie Irvine

- Harriet Coulter Joor

- Selina Bres

- Marie and Emilie De Hoa LeBlanc

- Cynthia Littlejohn

- Mazie T. Ryan

- Sarah (Sallie) Henderson

- Henrietta Bailey

- Frances Lawrence Howe Cocke

- Roberta Kennon

- Sara B. Levy

- Ada Lonnegan

- Mary Given Sheerer

- Leona Nicholson

- Amelie and Desiree Roman

Eventually the women who worked regularly with the Pottery were designated as craftsmen with a preference given to those who had completed an undergraduate degree and a later graduate studies program with the art department.[6]

As the Pottery grew and expanded, new craftsmen joined the program including:[6]

- Anna Frances Simpson

- Aurelia Arbo

- Juanita Gonzales

- Corinne Chalaron

- Lucia Arena

While the craftsmen did not typically pot their own pieces, they were responsible for creating and carving designs for each piece of pottery the program put out. During the lifespan of the Pottery, over 70,000 unique pieces were created and carved by the women.[7]

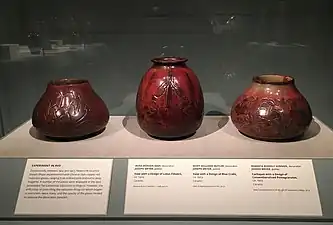

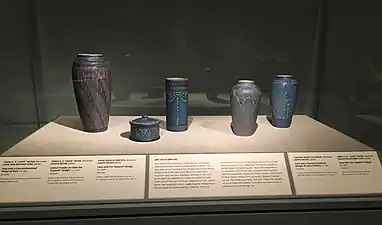

Pottery

Early pieces at the Pottery closely reflected the arts and crafts era in which the Pottery was operating. The pottery often depicted Louisiana's local flora, done in blue, yellow and green high glazes. The high point of Newcomb is generally considered to be from 1897 to 1917. During that period the Pottery experimented with various glazes and designs, and won numerous awards at various exhibitions throughout the country and in Europe. As the school entered the 1920s, new professors arrived and began to introduce influences from the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art. Highly carved pieces done in matt glazes of blue, green and pink marked this period. Perhaps one of the most famous Newcomb Pottery designs, the "Moon & Moss" style was introduced in this period.

Marks

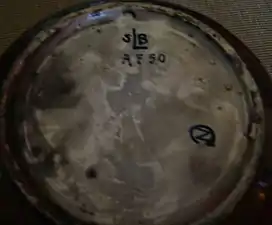

The Pottery used an elaborate system of marks to indicate a piece came from Newcomb College.[6] The marks would include an "N" inside of a "C" to indicate the school, along with the ciphers of the potter and craftsman who both created the piece.[6]

Also typically included would be a registration number indicating the year the piece was made.[6] The registration number for a Newcomb piece consisted of a letter or combination of letters to indicate the year the piece was made, along with a number from 1-100.[6] While most Newcomb pieces do have a registration number, some pieces, particularly earlier ones that were glazed but not otherwise decorated, do not.

In addition to the marks already mentioned, pieces prior to 1915 sometimes also had marks indicating the type of clay and glaze used for the piece.[6]

These marks include:

| Mark | Clay and glaze used | Years used |

|---|---|---|

| U | White clay | 1895–1902 |

| W | White clay | 1895–1908 |

| Q | Buff clay | 1895–1909 |

| R | Dark red clay | 1895–1910 |

| F | Dark red clay body with opaque glaze | 1895–1907 |

| FR | Dark red clay body with red glaze | 1895–1907 |

| B or B (enclosed in a circle) | Buff clay with a semi-matte glaze | 1910–1912 |

| C or C (enclosed in a circle) | Buff clay with a semi-matte glaze | 1913–1915 |

| A, D, E, F, G, K or T | White clay with a glass glaze | |

Newcomb Guild and the end of Newcomb Pottery

As tastes changed, and Arts & Crafts-style pottery became less popular and profitable for the College, the Pottery ceased production in 1940. It was replaced by the Newcomb Guild program that focused more on utilitarian wares, rather than the decorative pottery which symbolized the earlier Newcomb era.[6] Members of the earlier pottery program including Kenneth Smith, Francis Ford and Sadie Irvine continued producing pieces with the Newcomb Guild. However, the Newcomb Guild proved to be less popular than the earlier program and it effectively ended with Sadie Irvine's retirement in 1952.[6]

Smithsonian Institution Exhibitions

The Smithsonian Institution held an exhibition of Newcomb College Pottery in the Renwick Gallery of the American Art Museum from November 1984 to February 1985. That exhibition consisted of 210 Newcomb College Pottery pieces.[8] Approximately 30 years later, the Smithsonian put forward another exhibition of Newcomb College Pottery that ran from October 2013 to October 2016. This was a traveling exhibition which visited various cities around the United States, and displayed approximately 180 objects from the Newcomb College Pottery program, along with metalwork, jewelry, textiles and other objects made during the period the Pottery was in operation.[9]

Gallery

Various undecorated Newcomb College Pottery pieces showing a variety of forms

Various undecorated Newcomb College Pottery pieces showing a variety of forms Vase potted by Joseph Meyer and decorated by Sara Levy (1905)

Vase potted by Joseph Meyer and decorated by Sara Levy (1905) Example of Newcomb College Pottery marks from the Levy vase

Example of Newcomb College Pottery marks from the Levy vase Newcomb College Pottery vase potted and glazed by Joseph Meyer

Newcomb College Pottery vase potted and glazed by Joseph Meyer Example of Newcomb College Pottery marks from Meyer vase. This vase has no registration number, but dates from 1895-1907 due to the "FR" marking.

Example of Newcomb College Pottery marks from Meyer vase. This vase has no registration number, but dates from 1895-1907 due to the "FR" marking. Examples from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition showing a rare copper red reduction glaze

Examples from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition showing a rare copper red reduction glaze Vase with iris decoration, painted by Mary Given Sheerer (1898)

Vase with iris decoration, painted by Mary Given Sheerer (1898) Examples from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a cactus flower decoration

Examples from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a cactus flower decoration.jpg.webp) Vase with long stemmed flowers

Vase with long stemmed flowers Examples of Newcomb College Pottery showing art deco decoration

Examples of Newcomb College Pottery showing art deco decoration.jpg.webp) Example from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a repeating "red" cedar tree decoration

Example from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a repeating "red" cedar tree decoration.jpg.webp) Example from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a repeating blue crab decoration

Example from Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition with a repeating blue crab decoration.jpg.webp) Mug with oak tree decoration, painted by Marie de Hoa LeBlanc (1907)

Mug with oak tree decoration, painted by Marie de Hoa LeBlanc (1907)

References

- ↑ Poesch, Jessie J. & Spanola, Sally M. (1984). Newcomb Pottery: An Enterprise for Southern Women, 1895-1940.

- ↑ Newcomb Pottery: Its Makers and the Lessons They Are Teaching Southern Women. The Sunset, Vol.11. 1903.

- ↑ Lowe, John (2005). Bridging southern cultures: an interdisciplinary approach. pp. 133–153. ISBN 9780807130315.

- ↑ Cullison, William R. (1984). Two Southern Impressionists: An Exhibition of the Work of the Woodward Brothers, William and Ellsworth.

- ↑ admin. "Women, Art and Social Change: The Newcomb Pottery Enterprise".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Poesch, Jessie & Main, Sally (2003). Newcomb Pottery and Crafts: An Educational Enterprise for Women.

- ↑ Dalide, Monica (2008). 683 Things About New Orleans. pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Institution, Smithsonian. "Newcomb Pottery: An Enterprise for Southern Women". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ↑ "Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service - Women, Art, and Social Change: The Newcomb Pottery Enterprise".

External links

- Finding aid to the Newcomb College Art Department Collection on Newcomb Pottery, Newcomb Archives and Vorhoff Library Special Collections, Tulane University

- Finding aid to the Newcomb Pottery Records, Newcomb Archives and Vorhoff Library Special Collections, Tulane University

- Finding aid to the Newcomb Pottery Research Records, Newcomb Archives and Vorhoff Library Special Collections, Tulane University

- Newcomb Pottery Website