| New Britain campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

US Army soldiers returning from a patrol near Arawe, December 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 | 100,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

502 killed 1,575 wounded 4 missing | ~30,000 killed (mostly from disease and starvation)[1] | ||||||

The New Britain campaign was a World War II campaign fought between Allied and Imperial Japanese forces. The campaign was initiated by the Allies in late 1943 as part of a major offensive which aimed to neutralise the important Japanese base at Rabaul, the capital of New Britain, and was conducted in two phases between December 1943 and the end of the war in August 1945.

Initial fighting on New Britain took place around the western end of the island in December 1943 and January 1944, with US forces landing and securing bases around Arawe and Cape Gloucester. This was followed by a further landing in March 1944 around Talasea, after which little fighting took place between the ground forces on the island. In October 1944, the Australian 5th Division took over from the US troops and undertook a Landing at Jacquinot Bay the following month, before beginning a limited offensive to secure a defensive line across the island between Wide Bay and Open Bay behind which they contained the numerically superior Japanese forces for the remainder of the war. The Japanese regarded the New Britain Campaign as a delaying action, and kept their forces concentrated around Rabaul in expectation of a ground assault which never came.

The operations on New Britain are considered by historians to have been a success for the Allied forces. However, some have questioned the necessity of the campaign. In addition, Australian historians have been critical of the limited air and naval support allocated to support operations on the island between October 1944 and the end of the war.

Background

Geography

New Britain is a crescent-shaped island north east of the mainland of New Guinea. It is approximately 595 kilometres (370 mi) long, and its width varies from around 30 kilometres (19 mi) to 100 kilometres (62 mi); this makes it the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago. The interior of New Britain is rugged, with a range of volcanic mountains over 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) high running for most of its length.[2] The island's coast is indented by a large number of bays.[3]

The island has a tropical climate. At the time of World War II the mountains were covered by a rainforest of tall trees. The coastal plains which ring most of the island were covered in dense jungle. Most of the beaches on New Britain were backed by forested swamps, and a large number of rivers and streams ran from the mountains to the sea. All of these characteristics greatly complicated the movement of military units on New Britain. The number of sites suitable for amphibious landings was also constrained by the coral reefs which lay off most of the island's coastline.[3]

The island's population in 1940 was estimated as over 101,000 New Guineans and 4,674 Europeans and Asians.[4] Rabaul, located on the north-east coast of New Britain, was the main settlement on the island and the largest in the Bismarcks.[3] The town had served as the capital of the Australian-administered Territory of New Guinea since Australian forces had captured the region from Germany during 1914.[5]

Japanese occupation

Japanese forces captured New Britain in January 1942 as part of efforts to secure Rabaul,[6] quickly overwhelming the small Australian garrison during the Battle of Rabaul.[7] This invasion was undertaken to both prevent Allied forces from using Rabaul to attack the important Japanese base at Truk in the central Pacific, and to capture the town so that it could be used to support potential further Japanese offensives in the region.[8] While hundreds of Australian soldiers and airmen managed to escape and were evacuated between February and May, around 900 became prisoners of war and were treated harshly. The 500 European civilians captured by the Japanese were interned.[5] On 1 July 1942, 849 POWs and 208 civilian men who had been captured on New Britain were killed when the Montevideo Maru was torpedoed by an American submarine en route to Japan.[5] Most of the remaining European internees were transported to the Solomon Islands where they died due to poor conditions.[9]

The Japanese authorities adopted the Australian system of administering the island through village chiefs, and many villages shifted their loyalties to the Japanese to survive or to gain an advantage against other groups. The few chiefs who refused to cooperate with the Japanese were severely punished, with several being killed.[5] While the European women and children had been evacuated to Australia prior to the war, Asian people had not been assisted to leave. The Chinese-ethnic community feared that it would be massacred by Japanese forces, as had happened elsewhere in the Pacific, but this did not occur. However, men were forced to work as labourers and some women were raped and, in several cases forced to become "comfort women".[5]

Following the invasion, the Japanese established a large base at Rabaul. The facilities located near the town were attacked by Allied air units from early 1942, but these operations were generally unsuccessful. By mid-1943, a network of four airfields had been constructed at Rabaul which could accommodate 265 fighters and 166 bombers in protective revetments. More aircraft could also be accommodated in unprotected parking areas.[10] Aircraft based at these facilities operated against Allied forces in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.[11] The town was also developed into a major port, with extensive dock and ship repair facilities. Large stockpiles of supplies were stored in warehouses and open air dumps in and around Rabaul.[12] Few other Japanese facilities were constructed on New Britain, though a forward airfield was developed at Gasmata on the island's south coast. Both the Japanese and Australians maintained small parties of coastwatchers at other locations on New Britain; the Australians were civilians who had volunteered to remain on the island following the invasion.[9]

During 1943 small parties of Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) personnel, which comprised both Australian and New Guinean troops, were landed on New Britain. The AIB units sought to gather intelligence, re-assert Australian sovereignty and rescue downed Allied airmen. The Japanese attempted to hunt down the Allied coastwatchers and AIB patrols, and committed atrocities against civilians who assisted them. The AIB also trained and equipped New Guineans to serve as guerrillas, which led to a successful low-intensity campaign against the Japanese garrison. However, it also sparked tribal warfare with the guerrillas attacking villages they believed to have collaborated with the Japanese.[9]

Opposing forces

By 1943, there were more than 100,000 Japanese military and civilian personnel on New Britain and a smaller nearby island, New Ireland. These were centred on the headquarters of the Eighth Area Army, under the command of General Hitoshi Imamura: the 17th Division (11,429 personnel at the end of the war); the 38th Division (13,108); the 39th Brigade (5,073); the 65th Brigade (2,729); the 14th Regiment (2,444); the 34th Regiment (1,879) and the 35th Regiment (1,967). Together, these formations amounted to a force equivalent to four divisions. Naval troops provided the equivalent of another division.[13] By the end of the war, these Japanese forces were restricted to Rabaul and the surrounding Gazelle Peninsula.[6] These forces lacked naval and air support,[14] and were increasingly isolated and eventually cut-off from resupply due to Allied interdiction efforts, which meant that the garrison was largely left to its own devices.[15] Indeed, direct communications between Rabaul and Japan were severed in February 1943 and not reestablished until after the war.[16]

In contrast, United States, Australian and New Guinean forces, assisted by local civilians, were always a division-level command or smaller; the US "Director" Task Force which secured Arawe was effectively a regimental combat team based on the 112th Cavalry Regiment.[17] It was later followed by the 1st Marine Division before it handed over to the 40th Infantry Division, which in turn handed over to the Australian 5th Division.[6] This was due partly to a miscalculation of the size of the Japanese forces holding the island, as well as broader Allied strategy, which dictated a limited operation for New Britain, focused initially upon seizing and defending suitable locations for airbases, and then containment of the larger Japanese force.[6]

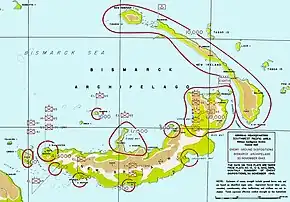

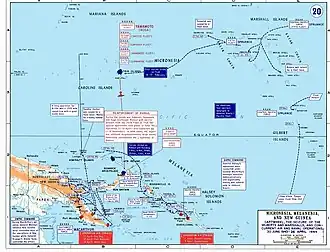

Preliminary operations

From mid-1942 Allied plans for the Pacific had a strong focus on capturing or neutralising Rabaul. In July 1942 the US military's Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered a two-pronged offensive against Rabaul. The forces assigned to the South Pacific Area were directed to capture the Solomon Islands, starting with Guadalcanal. Simultaneously, the units assigned to the South West Pacific Area, commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, were to secure Lae and Salamaua on the north coast of New Guinea. Once these operations were complete, forces from both commands would land on New Britain and capture Rabaul. This plan proved premature, however, as MacArthur lacked the forces needed to execute his elements of it. The Japanese offensive towards Port Moresby, which was defeated after months of heavy fighting in the Kokoda Track campaign, Battle of Milne Bay and Battle of Buna–Gona, also disrupted the Allied plans but left them in control of the territory needed to mount their own offensives.[18]

The Allies re-cast their plans in early 1943. Following a major conference, on 28 March the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a new plan for reducing Rabaul, which was designated Operation Cartwheel. Under this plan, MacArthur's forces were to establish airfields on two islands off the coast of New Guinea, capture the Huon Peninsula region of the mainland and land in western New Britain. The South Pacific Area was to continue its advance through the Solomon Islands towards Rabaul, culminating with a landing on Bougainville Island.[18] While the initial plans for Operation Cartwheel directed MacArthur to capture Rabaul, in June 1943 the Joint Chiefs of Staff decided that this was unnecessary as the Japanese base there could be neutralized by blockade and aerial bombardment. MacArthur initially opposed this change in plans, but it was endorsed by the British and United States Combined Chiefs of Staff during the Quebec Conference in August.[19]

The United States Fifth Air Force, the main American air unit assigned to the South West Pacific Area, began a campaign against Rabaul in October 1943. The goal of the attacks was to prevent the Japanese from using Rabaul as an air or naval base and to provide support for the planned landing on Bougainville scheduled for 1 November, as well as landings in western New Britain planned for December.[20] The first raid took place on 12 October, and involved 349 aircraft. Further attacks were made whenever weather conditions were suitable during October and early November.[21] On 5 November, two United States Navy aircraft carriers also attacked the town and its harbour. Following this attack the Imperial Japanese Navy ceased using Rabaul as a fleet base.[22] The campaign against Rabaul was intensified from November when air units operating from airfields on recently captured islands in the Solomons joined the attacks.[23]

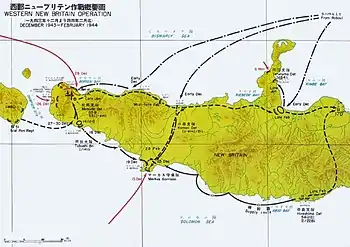

Invasion of western New Britain

Opposing plans

On 22 September 1943 MacArthur's General Headquarters issued orders for the invasion of New Britain, which was designated Operation Dexterity. These directed the US Sixth Army (which at the time was typically designated 'Alamo Force') to land forces in the Cape Gloucester region of western New Britain and at Gasmata to secure all of New Britain west of the line between Gasmata and Talasea on the north coast.[23] MacArthur's air commander, Lieutenant General George Kenney, opposed this operation as he believed that it would take too long to develop airfields at Cape Gloucester given the rapid pace of the Allied advances in the New Guinea region, and existing airfields were adequate to support the attacks on Rabaul and planned landings at other locations. However, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, the commander of Alamo Force, and MacArthur's naval commanders believed that it was necessary to invade New Britain to gain control of the strategic Vitiaz Strait through which it was planned to send convoys carrying Allied forces to locations in western New Guinea. However, the planned landing at Gasmata was cancelled in November due to concerns over the Japanese reinforcing the region and its proximity to the airfields at Rabaul, as well as the terrain being judged too swampy. Instead, on 21 November it was decided to capture the Arawe area on the south-west coast of New Britain to establish a base for PT boats and hopefully divert Japanese attention away from the main landing at Cape Gloucester.[24] After taking into account the availability of shipping and air cover, the landing at Arawe was scheduled for 15 December and that at Cape Gloucester for the 26th of that month.[25]

Alamo Force was responsible for developing plans for Operation Dexterity, with work on this having commenced in August 1943. Intelligence to inform these plans was sourced from Marine and Alamo Scout patrols which were landed in New Britain between September and December, as well as from aerial photography.[26] The US 1st Marine Division was the main formation selected for the Cape Gloucester landing; combined with artillery, transport, construction and logistics units this force was designated the Backhander Task Force.[27] The force selected for Arawe was built around the 112th Cavalry Regiment, which had been dismounted and was serving as infantry. The cavalry regiment was augmented with artillery and engineer units, with the overall force being designated the Director Task Force.[28]

The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assessed the strategic situation in the Southwest Pacific in late September 1943, and concluded that the Allies would attempt to break through the northern Solomon Islands and Bismarck Archipelago in the coming months en route to Japan's inner perimeter in the western and central Pacific. Accordingly, reinforcements were dispatched to strategic locations in the area in an attempt to slow the Allied advance. Strong forces were retained at Rabaul, however, as it was believed that the Allies would attempt to capture the town. At the time, Japanese positions in western New Britain were limited to airfields at Cape Gloucester on the island's western tip and several small way stations which provided small boats travelling between Rabaul and New Guinea with shelter from Allied aerial attacks.[29] As New Britain lay well to the east of the "Absolute National Defence Zone" which had been adopted by the Japanese military on 15 September, the overall goal for the forces there was to delay any Allied advances to buy time to improve the defences of more strategically important regions.[30]

During October the commander of the Eighth Area Army, Imamura, judged that the Allies next move would probably be an invasion of western New Britain. In response, he decided to dispatch further units to the area to reinforce its garrison, which was based around the under-strength 65th Brigade and designated Matsuda Force after its commander, Major General Iwao Matsuda.[31] The 17th Division was selected to provide troops for this purpose; the main body of this unit arrived in Rabaul from China on 4 and 5 October, having suffered around 1,400 casualties due to submarine and air attacks while en route to New Britain. The commander of the 17th Division, Lieutenant General Yasushi Sakai was appointed the new commander of the Japanese forces in western New Britain, but the division's battalions were spread across this region, southern New Britain and Bougainville.[32]

Arawe

For the Arawe operation, the Director Task Force, under the command of Brigadier General Julian Cunningham,[28] concentrated on Goodenough Island where they carried out training prior to embarking on 13 December 1943. In the weeks prior to the operation, Allied aircraft had carried out heavy attacks across New Britain, but the area around the landing beaches was purposefully left alone until the day prior to the landing in order not to alert the Japanese.[33] The ships carrying the invasion force arrived off the Arawe Peninsula, near Cape Merkus, around 03:00 on 15 December. Two small advanced elements set off almost immediately under the cover of darkness with orders to destroy a radio transmitter on Pilelo Island to the south-east and to sever the track leading towards the peninsula around Umtingalu village. The subsidiary landing around Umtingalu met with heavy resistance and was subsequently repulsed, while the landing on Pilelo proved more successful with the cavalrymen quickly overwhelming a small Japanese force before securing their objective.[34]

Meanwhile, after a deal of confusion while the troops embarked in their landing craft, the main assault began after 06:25, supported by a heavy naval and aerial bombardment.[35] Opposition ashore was limited as there were very few Japanese in the vicinity, although the first wave experienced machine-gun fire that was quickly dealt with. Japanese aircraft from Rabaul sortied over the landing beach, but were chased away by US fighters flying combat air patrols. Further confusion resulted in a delay in bringing the second wave in, while the final three waves got mixed up and landed at the same time. Nevertheless, the US cavalrymen quickly secured a beachhead and by the afternoon they had secured the Amalut Plantation and established a strong defensive position across the base of the Arawe Peninsula. In the days that followed Japanese reinforcements arrived and they subsequently launched a counterattack, but the Americans also brought in reinforcements, including tanks, and the counterattack was repelled. In the aftermath, the Japanese withdrew further inland towards a nearby airfield and the fighting around Arawe petered out.[36]

Cape Gloucester

The landing at Cape Gloucester took place on 26 December 1943, following the diversionary action around Arawe,[37] and a series of practice landings around Cape Sudest a few days earlier.[38] The 1st Marine Division, under the command of Major General William H. Rupertus was selected for the attack.[39] For the landing, two beaches were chosen to the east of the airfields at Cape Gloucester, which was the main goal of the operation. A subsidiary landing site was also chosen on the opposite side of the cape to the west of the airfields. Troops from the 7th Marines embarked from Oro Bay. Escorted by US and Australian warships from Task Force 74, en route they were reinforced by the 1st Marines and artillery from the 11th Marines.[40] A heavy aerial bombardment was directed against Cape Gloucester's garrison in the weeks before the landing which destroyed many of the fixed defences and affected the soldiers' morale.[41] The strikes continued on 26 December prior to the assault, resulting in heavy smoke which partially obscured the beaches.[40] The American landing was successful, with counter-attacks by Japanese forces on 26 December being defeated. The next day the 1st Marine Regiment advanced west, towards the airfields. A Japanese blocking position was reduced that afternoon, but the American advance was halted while reinforcements were landed. It resumed on 29 December, with the airfields being captured.[42] During the first two weeks of January 1944 the Marines advanced south from their beachhead to locate and defeat the Japanese force they believed was in the area. This led to some heavy fighting, with the Japanese 141st Infantry Regiment attempting to defend positions located on high ground.[43] The Marines eventually secured the area on 16 January.[44]

With the successful landing, the Allies effectively gained control of the sea lanes of communication to the Bismarck Sea, having secured lodgements on either side of the Vitiaz Strait, after earlier capturing Finschhafen. In January 1944, the Allies sought to press their advantage further, launching another Dexterity operation on the New Guinea coast with a landing at Saidor as the Huon Peninsula was cleared by Australian and US forces. In response, the Japanese high command at Rabaul ordered their forces that were withdrawing from the Huon Peninsula to bypass Saidor, and they subsequently began withdrawing towards Madang.[45]

In mid-January, Sakai requested permission to withdraw his command from western New Britain, and this was granted by Imamura on the 21st of the month. The Japanese forces subsequently sought to disengage from the Americans, and move towards the Talasea area.[46] Marine patrols pursued the Japanese, and a large number of small engagements were fought in the centre of the island and along its north coast.[47]

Talasea

In the months following the operations to secure Arawe and Cape Gloucester, there was only limited fighting on New Britain as Japanese forces largely chose to avoid combat during this period and continued their withdrawal towards Rabaul. US forces secured Rooke Island in February 1944, but by then the island's garrison had already been withdrawn.[43] The following month, a further landing was undertaken at Talasea, on the Willaumez Peninsula. Conceived as a follow-up operation to cut off the withdrawing Japanese,[48] the operation involved a regimental combat team formed primarily from the 5th Marines landing on the Willaumez Peninsula, on the western side of a narrow isthmus near the Volupai Plantation. Following the initial landing, the Marines advanced east towards the emergency landing strip at Talasea on the opposite coast. A small group of Japanese defenders held up the US troops and prevented them from advancing quickly enough to cut off the withdrawal of the main Japanese force falling back from Cape Gloucester.[49][50]

The Allied air attacks on Rabaul were further intensified following the completion of airfields on Bougainville during January 1944. All of the town was destroyed, along with a large number of aircraft and ships. The Japanese Army lost relatively little equipment though, as its stockpiles had been moved into volcanic caves during November. Due to the shipping losses, the Japanese stopped sending any further surface vessels to the town from February.[51] The Japanese air units stationed at Rabaul made their last attempt to intercept an Allied raid on the area on 19 February. Following this, the air raids which continued to the end of the war were contested only by anti-aircraft gunfire.[52] As a result of its prolonged bombardment, the town ceased to be a base from which the Japanese could contest the Allied advance. However, it remained very well defended by a garrison of around 98,000 men and hundreds of artillery and anti-aircraft guns. Extensive fortifications were constructed around the Gazelle Peninsula, where rugged terrain would have also favoured the defenders.[53] On 14 March 1944 the Imperial General Headquarters directed the Eighth Area Army to "hold the area around Rabaul for as long as possible" to divert Allied forces away from other regions.[54]

In April 1944, once Arawe and Cape Gloucester had been secured, the US 40th Infantry Division under Major General Rapp Brush[55] arrived to relieve the Marines and cavalrymen that had landed in December 1943. After this, a period of relative inactivity followed as the US and Japanese forces occupied opposite ends of the island, while guerilla actions were fought in the centre by Australian-led forces of the AIB.[6] Patrols from the AIB were subsequently successful in pushing back Japanese outposts to Ulamona on the north coast, and to Kamandran in the south.[56][57] In mid-1944, the headquarters of the Eighth Area Army re-assessed Allied intentions on New Britain. While up to this time it had been believed that the Allies were planning a major assault on Rabaul, the advance of Allied forces towards the Philippines was interpreted to mean that this was no longer likely. Instead, the Japanese judged that the Allies would advance slowly across New Britain towards the town and attack it only if their campaign towards Japan became bogged down or concluded, or if the size of Australian forces on the island was increased.[58]

Australian operations

Transfer to Australian responsibility

In October 1944, the decision was made to transfer the US 40th Infantry Division to fight in the Philippines, with responsibility for New Britain passing to the Australians in line with the Australian government's desire to use their own troops to recapture the Australian territory the Japanese had taken earlier in the war.[59] The Australian 5th Division, commanded by Major General Alan Ramsay, was chosen for this operation, having concentrated around Madang in May 1944 following operations to secure the Huon Peninsula.[60]

Allied intelligence at the time had underestimated Japanese strength on the island, believing it to be held by around 38,000 men. While this was incorrect by a factor of two, Allied assessments of Japanese intentions were more accurate, with planners believing that Imamura's force would adopt a defensive posture, remaining largely inside the fortifications that had been established around Rabaul.[61] In fact Japanese combat strength was approximately 69,000 men, including 53,000 army troops and 16,000 sailors, and while they were mainly located in the Gazelle Peninsula in the north around Rabaul, there were watching-stations established as far forward as Awul. Due to the garrison's increasing isolation many were involved in growing rice and gardening. With American enclaves at Talasea–Cape Hoskins, Arawe and Cape Gloucester, the two sides were geographically separated and observing a tacit truce. Allied bombing had heavily reduced Japanese air and naval forces to the extent that there were only two operational aircraft left, and the only vessels that remained were 150 barges that could move small amounts of supplies or troops around the coast.[14]

Ramsay's force was ordered to carry out a containment operation designed to isolate the Japanese garrison on the Gazelle Peninsula.[6] In doing so, Ramsay was ordered to keep the pressure on the Japanese while avoiding committing large-scale forces. Nevertheless, it was decided that the Australians would carry out a limited offensive, consisting largely of patrol actions, with the goal of advancing beyond the western tip of the island where the US garrison had remained. To achieve this, the Australian commanders decided to establish two bases: one around Jacquinot Bay on the southern coast, with a supporting base on the north coast around Cape Hoskins.[6][61]

Central New Britain

In early October 1944, the 36th Infantry Battalion was landed at Cape Hoskins to begin taking over from the US garrison.[62] Early the next month, the remaining elements of the Australian 6th Infantry Brigade landed at Jacquinot Bay. In the weeks that followed, large amounts of stores and equipment were landed, along with support personnel and labourers to begin construction on facilities including roads, an airstrip, dock facilities, and a general hospital. This work would last until May 1945.[63] Two squadrons of Royal New Zealand Air Force Corsair fighter bombers were later flown in to support Allied operations on the island,[64] and US landing craft from the 594th Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment provided support until the Australian Landing Craft Company arrived in February 1945.[65]

Due to limited shipping resources, the transfer of the 5th Division was delayed significantly and was not completed until April 1945. Nevertheless, in December, the Australian advance began with the goal of moving along the northern and southern coasts towards the Gazelle Peninsula to capture a line between Wide Bay and Open Bay, along which to contain the larger Japanese force, which remained largely static around the Rabaul fortress, with only about 1,600 troops deployed in the forward areas.[66] This saw a series of amphibious landings, river crossings and small-scale actions.[67] The 36th Infantry Battalion began expanding their foothold around Cape Hoskins in early December pushing forward towards Bialla via barge, where two companies established a forward base from where they began patrolling east. After establishing that the Japanese had withdrawn behind the Pandi River, a new base was established around Ea Ea, with the troops again being moved forward by barge. The 1st New Guinea Infantry Battalion arrived to reinforce them in January 1945.[68] After this, the Australians on the north coast pushed their line towards Open Bay, establishing an outpost around Baia and patrolling the Mavelo Plantation, during which several minor skirmishes were fought.[69]

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, on the southern coast, the main advance towards Wide Bay had begun in late December. This involved establishing a forward base around Milim in mid-February 1945 by the 14th/32nd Infantry Battalion, which was moved by barge via Sampun.[69] On 15 February, Kamandran was captured following a brief fight during which a patrol from the 1st New Guinea Infantry Battalion carried out a successful ambush.[68][70] At this point, Japanese resistance on the southern coast began to grow and in the final phase of the advance, the Australians began advancing on foot around Henry Reid Bay, to secure the Waitavalo–Tol area, which was held by a Japanese force around battalion strength.[66]

After this, a series of engagements took place over a six-week period to reduce the main Japanese position around Mount Sugi, commencing with the 19th Infantry Battalion's assault across the Wulwut River on 5 March.[71] The position around Mount Sugi, which stretched across a number of ridges to the west of the Wulwut, was strongly defended with mortars, machine guns and pillboxes, and heavy rain also frustrated Australian attempts to reduce the Japanese stronghold. Fierce fighting followed, culminating with the 14th/32nd's attack on Bacon Hill on 18 March. Following the capture of Waitavalo–Tol area in March and April, the Australians exploited towards Jammer Bay and sent patrols to link up their northern and southern drives.[72] They also brought in reinforcements, first from the 13th Infantry Brigade and then the 4th,[73] as the offensive part of their campaign effectively came to an end. In the months that followed, the Australians mounted a series of patrols aimed at maintaining the line around the neck of the Gazelle Peninsula to prevent any attempt by the Japanese to break out from Rabaul. This lasted until the end of the war in August 1945.[67] The 2/2nd Commando Squadron conducted a patrol which penetrated close to Rabaul, and judged that the terrain was so rough it would not be possible for large Japanese units to move over it to attack the Australian forces.[74]

A series of command changes had occurred around this time. In April, Major General Horace Robertson took over command from Ramsay, while Major General Kenneth Eather assumed control in early August.[75]

Aftermath

Rabaul was secured by the 29th/46th Infantry Battalion, which formed part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, on 6 September 1945, at which time over 8,000 former prisoners of war were liberated from Japanese camps on the island. Australian losses during the fighting on New Britain between October 1944 and the end of the war were limited, amounting to 53 killed and 140 wounded. A further 21 died from non-battle injuries or illnesses.[76] Losses amongst the US 1st Marine Division amounted to 310 killed and 1,083 wounded.[77] In addition, casualties for all Allied units during the fighting around Arawe came to 118 killed and 352 wounded, with four missing.[38] Total Japanese losses in New Britain and the other islands in the Bismarck Archipelago are estimated at around 30,000 dead, mostly from disease and starvation.[1]

.jpg.webp)

In the aftermath of the campaign, there are mixed opinions among historians as to whether the US landings around Arawe, and even around Cape Gloucester were necessary. While according to Henry Shaw and Douglas Kane, authors of the Marine Corps official history, the landing around Arawe arguably made the landing at Cape Gloucester easier,[78] US naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison argues that the landing at Arawe was of "small value" pointing out that it was never developed into a naval base and that potentially the resources and manpower could have been employed elsewhere.[79] US Army historian John Miller also concluded that the operations to secure Arawe and Cape Gloucester "were probably not essential to the reduction of Rabaul or the approach to the Philippines", while there were some benefits to the offensive in western New Britain and comparatively few casualties.[80]

In summarising the Australian involvement in the campaign, Gavin Long, the Australian official historian, wrote that it was inadequately resourced, particularly in terms of air and sea power, with the latter delaying the concentration of the 5th Division until very late in the campaign.[81] Regardless, Long writes that the Australian force, which was relatively inexperienced and matched against a Japanese force of around five divisions, achieved a remarkable result in the circumstances.[66] Lachlan Grant also reaches a similar conclusion, highlighting the limited casualties that were sustained in the campaign in comparison to those in other locations such as Aitape–Wewak.[82] Retired General John Coates judged that "in many respects Australian operations on New Britain had been a classic containment campaign", but contrasted the insufficient air and naval support for them with the excesses of both which had been allocated to the Borneo Campaign.[83] Peter Charlton also regarded the Australian operations as successful, but was critical of both the decision to deploy the 5th Division against a much more powerful Japanese force and the limited support provided for the campaign.[84]

The defensive tactics of the Japanese commander, Imamura, were likely a factor in ensuring the successful containment by the much smaller Australian force. According to Japanese historian Kengoro Tanaka, Imamura had been under orders to preserve his strength until mutual action could be achieved with the Imperial Japanese Navy and had as such, chosen to deploy only a small portion of his troops forward of the fortress of Rabaul.[85] Eustace Keogh concurs with this assessment, arguing that any offensive would have lacked strategic purpose without sufficient naval and air support, which at the time was unavailable to the Japanese.[72] Gregory Blake has written that the extremely rugged terrain made a large Japanese offensive impossible.[74]

See also

- Attack! The Battle of New Britain: a documentary/propaganda film produced by the US military in 1944.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Australian War Memorial. "Australia-Japan Research Project: Dispositions and deaths". Citing figures of the Relief Bureau of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, March 1964. 30,500 Japanese troops are listed as dying in the Bismarck Archipelago.

- ↑ Rottman 2002, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 Rottman 2002, p. 185.

- ↑ Rottman 2002, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moremon, John. "Rabaul, 1942 (Longer text)". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grant 2016, p. 225.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 100–111.

- ↑ Frei, Henry. "Why the Japanese were in New Guinea (Symposium paper)". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Moremon, John. "New Britain, 1944–45 (Longer text)". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Mortensen 1950, p. 312.

- ↑ Shindo 2001.

- ↑ Mortensen 1950, pp. 312–313.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 268–270.

- 1 2 Dennis et al 2008, p. 390.

- ↑ Tanaka 1980, pp. 127–130.

- ↑ Hiromi 2004, pp. 138 & 146.

- ↑ Rottman 2009, pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 Horner, David. "Strategy and Command in Australia's New Guinea Campaigns (Symposium paper)". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Mortensen 1950, pp. 316, 318.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 230–232.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 253.

- 1 2 Miller 1959, p. 270.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 273–274.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 278–279.

- 1 2 Miller 1959, p. 277.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 324–325.

- ↑ Shindo 2016, p. 52.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 280.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 326–327.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 338.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 338–339.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 339.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 339–340.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 340.

- 1 2 Miller 1959, p. 289.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 277–279.

- 1 2 Miller 1959, pp. 290–292.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 443–444.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 290–294.

- 1 2 Miller 1959, p. 294.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 389.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 340–341.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 398.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 399–408.

- ↑ Hough & Crown 1952, p. 152.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 411–427.

- ↑ Hough & Crown 1952, pp. 152–171.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 309–310.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 311.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Shindo 2016, p. 59.

- ↑ Hough & Crown 1952, p. 183.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 408.

- ↑ Powell 1996, pp. 239–245.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Dennis et al 2008, p. 387.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 395, 410–411.

- 1 2 Keogh 1965, p. 410.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Mallett 2007, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Bradley 2012, p. 408.

- ↑ Long 1963, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 Long 1963, p. 270.

- 1 2 Grant 2016, pp. 225–226.

- 1 2 Keogh 1965, p. 411.

- 1 2 Long 1963, p. 253.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 256–257.

- 1 2 Keogh 1965, p. 412.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 260–261.

- 1 2 Blake 2019, p. 253.

- ↑ Long 1963, p. 265.

- ↑ Grant 2016, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 295.

- ↑ Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 343.

- ↑ Morison 2001, p. 377.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Long 1963, pp. 250 & 269.

- ↑ Grant 2016, p. 226.

- ↑ Coates 2006, p. 276.

- ↑ Charlton 1983, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Tanaka 1980, p. 127.

Bibliography

- Blake, Gregory (2019). Jungle Cavalry: Australian Independent Companies and Commandos 1941-1945. Warwick, United Kingdom: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-911628-82-8.

- Bradley, Philip (2012). Hell's Battlefield: The Australians in New Guinea in World War II. Crow's Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-270-9.

- Charlton, Peter (1983). The Unnecessary War: Island Campaigns of the South-West Pacific, 1944–45. South Melbourne: Macmillan Company of Australia. ISBN 978-0-333-35628-9.

- Coates, John (2006). An Atlas of Australia's Wars (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-555914-9.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Grant, Lachlan (2016). "Campaigns in Aitape–Wewak and New Britain, 1944–45". In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–231. ISBN 978-1-107-08346-2.

- Hiromi, Tanaka (2004). "Chapter 7: Japanese force in post-surrender Rabaul" (PDF). From a Hostile Shore: Australia and Japan at War in New Guinea. Bullard, Steven and Akemi, Inoue (translators). Canberra: Australia–Japan Research Project, Australian War Memorial. pp. 138–152. ISBN 978-0-975-19040-1.

- Hough, Frank O.; Crown, John A. (1952). The Campaign on New Britain. Washington, DC: Historical Division, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 63151382.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne: Grayflower Publications. OCLC 7185705.

- Long, Gavin (1963). "Chapter 10: Operations on New Britain". The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. VII (1st ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 241–270. OCLC 1297619.

- Mallett, Ross A. (2007). Australian Army Logistics 1943–1945 (PhD thesis) (online ed.). University of New South Wales. OCLC 271462761. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Miller, John Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 63151382.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001) [1958]. Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06997-0.

- Mortensen, Bernhardt L. (1950). "Rabaul and Cape Gloucester". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. IV. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 978-0-912799-03-2.

- Powell, Alan (1996). War by Stealth: Australians and the Allied Intelligence Bureau 1942–1945. Carlton South, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84691-1.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2009). World War II US Cavalry Units. Pacific Theater. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-451-0.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Isolation of Rabaul. Vol. II. Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 482891390.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Shindo, Hiroyuki (2001). "Japanese Air Operations Over New Guinea During the Second World War". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (34). ISSN 1327-0141.

- Shindo, Hiroyuki (2016). "Holding on to the Finish: The Japanese Army in the South and South West Pacific 1944–45". In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–76. ISBN 978-1-107-08346-2.

- Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.

Further reading

- Gamble, Bruce (2013). Target Rabaul: The Allied Siege of Japan's Most Infamous Stronghold, March 1943 – August 1945. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4407-1.