The National Launch System (or New Launch System) was a study authorized in 1991 by President George H. W. Bush to outline alternatives to the Space Shuttle for access to Earth orbit.[1] Shortly thereafter, NASA asked Lockheed Missiles and Space, McDonnell Douglas, and TRW to perform a ten-month study.[2]

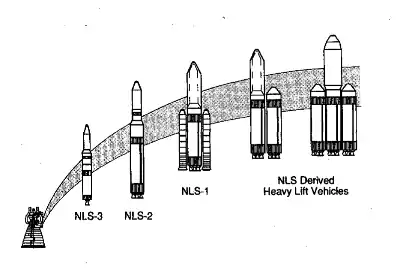

A series of launch vehicles was proposed, based around the proposed Space Transportation Main Engine (STME) liquid-fuel rocket engine. The STME was to be a simplified, expendable version of the Space Shuttle main engine (SSME).[3][4] The NLS-1 was the largest of three proposed vehicles and would have used a modified Space Shuttle external tank for its core stage. The tank would have fed liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen to four STMEs attached to the bottom of the tank. A payload or second stage would have fit atop the core stage, and two detachable Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters would have been mounted on the sides of the core stage as on the Shuttle.[3] Period illustrations suggest that much larger rockets than NLS-1 were contemplated, using multiples of the NLS-1 core stage.[5][6]

Program cancellation

The NLS program did not venture beyond the planning stages and did not survive the Presidency of Bill Clinton, which started in January 1993. In 1992, Daniel Goldin was selected to replace Vice Admiral Richard H. Truly as NASA administrator. Goldin championed the motto, "faster, better, cheaper,"[7] which may not have fit the ambitious NLS vision. A NASA history from 1998 says that reusable single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) rockets and space planes such as the McDonnell Douglas DC-X and the Lockheed Martin X-33 seemed attainable and represented smaller, simpler alternatives to the sprawling Shuttle program.[8] The NLS, by contrast, was more of a continuation of the Shuttle legacy. By the beginning of the Clinton administration, the expensive Space Shuttle and planned Space Station Freedom programs had enough momentum to continue, and the SSTO projects showed enough promise to fund. There was no money left for another big program such as the NLS.

Legacy

In 1994, the United States Air Force Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program led to the development of the Delta IV. Rocketdyne realized that they would need a powerful, simple engine for the proposed liquid-fueled Common Booster Core (CBC). NLS research on the STME, a simpler SSME, served as a starting point for the greatly simplified RS-68 that powered the Delta IV EELV rocket.[9] The Delta IV Heavy rocket is composed of three CBCs.[10]

NASA later developed a very similar launch vehicle to NLS-1 called the Space Launch System, as part of its Artemis program to return astronauts to the Moon in the mid-2020s. The similarities include a lengthened Shuttle external tank-like core stage, four engines meant as expendable versions of the SSME, and large solid rocket boosters (with five segments instead of four).[11][12][13][14][15]

See also

- Space Launch System (since 2010)

- Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee (2009)

- First Lunar Outpost

- DIRECT (since 2006)

- Exploration Systems Architecture Study (2005)

- Vision for Space Exploration (since 2004)

- Space Launch Initiative (ca. 2002 - 2004)

- Space policy of the United States (1996)

- Advanced Transportation System Studies (1992–1994)

- Rockwell X-30 (ca. 1990 - 1993)

- Advisory Committee on the Future of the United States Space Program (1990)

- Space Exploration Initiative (1989)

- Advanced Launch System (1987–1990)

- List of space launch system designs

- Studied Space Shuttle Variations and Derivatives

Notes

- ↑ Bush 1991.

- ↑ Flight International 1991, p. 12.

- 1 2 Lyons 1992, p. 19.

- ↑ Federation of American Scientists 1996.

- ↑ Lyons 1992, Figure 1.

- ↑ Duffy, Lehner & Pannell 1993, Figure 1.

- ↑ Thompson & Davis 2009.

- ↑ NASA History Division 1998.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 1.

- ↑ Boeing 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (31 March 2011). "NASA to set exploration architecture this summer". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (14 September 2011). "SLS finally announced by NASA – Forward path taking shape". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (25 April 2011). "SLS planning focuses on dual phase approach opening with SD HLV". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (16 June 2011). "Managers SLS announcement after SD HLV victory". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ "Space Launch System Reference Guide". NASA. 2 March 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

References

- Boeing (2005), "Delta IV Heavy growth options for space exploration", Delta Launch 310 – Delta IV Heavy Demo Media Kit (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2007, retrieved April 25, 2010

- Bush, George H. W. (1991), National Space Launch Strategy NSPD-4, July 10, 1991, retrieved April 25, 2010

- Duffy, J. B.; Lehner, J. W.; Pannell, B. (1993). "Evaluation of the national launch system as a booster for the HL-20". Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 30 (5): 622. Bibcode:1993JSpRo..30..622D. doi:10.2514/3.25574.

- Federation of American Scientists (1996), National Launch System - NLS, retrieved April 25, 2010

- Flight International (August 28 – September 3, 1991), "NASA Sets up 10-month NLS study", Flight International, 4 (4282), retrieved April 25, 2010

- Lyons, Michael T. (1992), "National launch system and its potential application to the launch of geosynchronous satellites." (PDF), AIAA International Communication Satellite Systems Conference and Exhibit, 14th, Washington, D. C., March 22-26, 1992, Technical Papers. Pt. 1 (A92-29751 11-32)., American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, pp. 18–22, archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2015, retrieved April 25, 2010

- NASA History Division (September 23, 1998), "The Policy Origins of the X-33 Part II: The NASA Access to Space Study", X-33 History Project, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, archived from the original on October 22, 2014, retrieved April 25, 2010

- Thompson, Elvia; Davis, Jennifer (November 4, 2009), Daniel Saul Goldin NASA Administrator, April 1, 1992 - November 17, 2001, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, archived from the original on December 8, 2016, retrieved April 25, 2010

- Wood, B. K. (2002), "Propulsion for the 21st Century—RS-68", 38th Joint Liquid Propulsion Conference, Indianapolis, Indiana. July 2002. Reston, Virginia, USA., American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, archived from the original on March 19, 2009, retrieved April 25, 2010

External links

- EELV - Boeing Contains good summary of NLS from an early 1990s perspective.

- Cycle 0(CY1991) NLS trade studies and analyses report. Book 1: Structures and core vehicle

- Cycle O (CY 1991) NLS trade studies and analyses, book 2. Part 1: Avionics and systems

- Cycle O(CY1991) NLS trade studies and analyses report. Book 2, part 2: Propulsion

- Many documents on NLS are available at the NASA Technical Reports Server, administered by the NASA Scientific and Technical Information Program Office. Search term: NLS