| Nathu La | |

|---|---|

Chumbi Valley visible from the Indian side (center). The main gate between the two sides (bottom). The stone walls were constructed in a build-up to the 2006 reopening.[1] | |

| Elevation | 4,310 m (14,140 ft)[2][3] |

| Location | Sikkim, India – Tibet, China |

| Range | Dongkya Range, Himalaya |

| Coordinates | 27°23′13″N 88°49′51″E / 27.38681°N 88.83095°E |

Nathu La  Nathu La | |

| Nathu La |

|---|

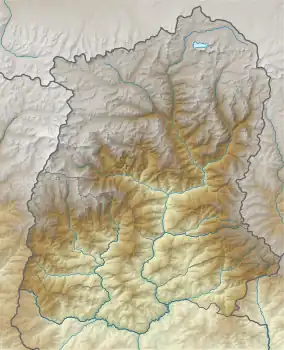

Nathu La[lower-alpha 1](Tibetan: རྣ་ཐོས་ལ་, Wylie: Rna thos la, THL: Na tö la, Sikkimese: རྣ་ཐོས་ལ་) is a mountain pass in the Dongkya Range of the Himalayas between China's Yadong County in Tibet, and the Indian states of Sikkim. But minor touch of Bengal in South Asia. The pass, at 4,310 m (14,140 ft), connects the towns of Kalimpong and Gangtok to the villages and towns of the lower Chumbi Valley.

The pass was surveyed by J. W. Edgar in 1873, who described the pass as being used for trade by Tibetans. Francis Younghusband used the pass in 1903–04, as did a diplomatic British delegation to Lhasa in 1936–37, and Ernst Schäfer in 1938–39. In the 1950s, trade in the Kingdom of Sikkim used this pass. Diplomatically sealed by China and India after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the pass saw skirmishes between the two countries in coming years, including the clashes in 1967 which resulted in fatalities on both sides. Nathu La has often been compared to Jelep La, a mountain pass situated at a distance of 3 miles (4.8 km).

The next few decades saw an improvement in ties leading to the re-opening of Nathu La in 2006. The opening of the pass provides an alternative route to the pilgrimage of Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar, and was expected to bolster the economy of the region by playing a key role in the growing Sino-Indian trade. However, while trade has had a net positive impact, it under-performed,[13] and is limited to specific types of goods and to specific days of the week. Weather conditions including heavy snowfall restricts border trade to around 7 to 8 months.

Roads to the pass have been improved on both sides. Rail routes have been brought closer. It is part of the domestic tourist circuit in south-east Sikkim. Soldiers from both sides posted at Nathu La are among the closest along the entire Sino-India border. It is also one of the five Border Personnel Meeting points between the two armies of both countries. 2020 border tensions and the coronavirus pandemic have affected tourism and movement across the pass.

Name and meaning

The name "Nathu La" is traditionally interpreted as "the whistling pass",[14] or more commonly as the "listening ears pass".[15][16] The Chinese government explains it as "a place where snow is deepest and the wind strongest".[17] According to G. S. Bajpai, it means "flat ground from where the hill features gradually rise to right and left".[18] Lepcha people who are native to the region call it ma-tho hlo/na tho lo; which may have possibly evolved to the present usage of the word.

Geography

Nathu La is a mountain pass on the Dongkya Range that separates Sikkim and the Chumbi Valley at an elevation of 14,250 feet (4,340 m).[19][lower-alpha 2] The pass is 52–54 kilometres (32–34 mi) east of Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim,[21][20] and 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Yatung Shasima, the headquarters of the Yadong County (or the Chumbi Valley).[22]

Nathu La is one of the three frequently-used passes between Sikkim and the Chumbi Valley, the other two being Cho La and Jelep La. Historically, Nathu La served Gangtok, while Cho La served the former Sikkim capital Tumlong and Jelep La served Kalimpong in West Bengal.[23] Nathu La is mere 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Jelep La, as the crow flies,[24] but the travel distance could be as much as 10 miles (16 km).[19] On the Tibetan side, the Chola route led to Chumbi, the Nathu La route led to a village called Chema and the Jelep La route led to Rinchengang, all in the lower Chumbi Valley.

Even today, heavy snowfall causes the closure of the pass, with temperatures as low as −25 °C (−13 °F) and strong winds.[25]

History

The Nathu La and Jelep La passes were part of the trade routes of the British Empire during the 19th and early 20th century.[16]

British Empire

The British Raj brought the Kingdom of Sikkim under their protectorate in 1861 and wished to promote trade with Tibet through Sikkim. In 1873, J. W. Edgar, the Deputy commissioner at Darjeeling, was asked to investigate the trading conditions and make recommendations for a preferred route.[26] Edgar reported active trade running through the Nathu La pass ("Gnatui pass" in his terminology), which was linked to Gangtok as well as Darjeeling.[27] The traders found significantly higher value for their goods at Darjeeling than at Gangtok.[28] However, Edgar preferred the neighbouring Jelep La pass on physical grounds, and recommended building a road to that pass along with a trade mart close to it.[29] Edgar wrote,

On the whole, I am not inclined to recommend that Guntuck [Gangtok] should be chosen for the mart, and rather think that ... Dumsong [Damsang] might be preferable to any of the lower elevations of Sikhim. It is true that the distance from the Jeylep Pass [Jelep La] to Dumsong is greater than that from the Gnatui to Guntuck,.... But to counterbalance this, the best route from the Thibet boundary to the foot of the Chola range is that by the Jeylep Pass.[30]

In 1903–04 Francis Younghusband led a British military expedition into Lhasa consisting of 1,150 soldiers and over 10,000 support staff and pack animals.[31] The first choice of crossing into the Chumbi Valley had been a pass north of Nathu La, the Yak La.[32] Yak La provided the shortest route from Gangtok to Sikkim's eastern frontier, however the eastern descent proved too steep and dangerous.[32] Both Nathu La and Jelep La were used by the expedition, with Nathu La becoming the main communication channel.[33]

In 1936–37, a diplomatic British delegation to Lhasa including B. J. Gould and F. S. Chapman used the Nathu La pass.[34][35] Chapman writes that during their journey from Gangtok to Nathu la, just at the foot of the pass, was a road leading to the right and a signbord indicating Kupup.[36] This route would have put them onto the Kalimpong-Lhasa route via Jelep La.[36] Chapman writes that "From Gangtok the mule-track starts for the Natu La, and from Kalimpong the longer and more difficult road leaves for the Jelep La. By these two passes the road from Lhasa crosses the main range of the Himalaya on its way to India..." [37] Chapman goes on to write that from the summit of the pass, if it were not for the mist, the delegation would have been able to see Chomolhari.[38] At the summit, Chapman writes of groups of stones and prayer flags these were not only for the protection of travelers, but they marked the boundary between Sikkim and Tibet.[38] The road near the pass was paved with stones.[38] The first stop after the pass was Champithang,[38] a resting place for the British on the way to Lhasa.[39]

In 1938–39 Ernst Schäfer led a German expedition to Tibet legally via Nathu La on the orders of Heinrich Himmler.[40][41] This expedition also came across no gates or barriers at the pass, the border; only a ladze, prayer flags and a cairn.[42]

Post founding of PRC and independent India

In 1949, when the Tibetan government expelled the Chinese living there, most of the displaced Chinese returned home through the Nathu La–Sikkim–Kolkata route.[43]

The Kingdom of Sikkim had flourishing trade during the 1950s. Calcutta was linked with Lhasa via Chumbi Valley, with Nathu La being one of the main routes for passage. The majority of trade between China and India during those years was via this route.[44] Some traders from India even set up their shop in Yadong.[44] Goods exported to China included medicines, fuel, and disassembled cars. India imported wool and silk.[44][45] Mules and horses would be the main transit vehicle during those years.[45]

Construction to make the Gangtok–Nathu La road motorable started in 1954.[46] It was completed and formally opened in the presence of the Maharaja of Sikkim by Jawaharlal Nehru on 17 September 1958.[46][47] At the time the motorable road ended at Sherathang.[46] However, the Chinese did not take up the construction of the road on their side at the time.[46] The Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, used this pass to travel to India for the 2,500th birthday celebration of Gautama Buddha, in the autumn of 1956.[45][48]

.jpg.webp)

After the People's Republic of China took control of Tibet in 1950 and suppressed a Tibetan uprising in 1959, the passes into Sikkim became a conduit for refugees from Tibet.[49] During the 1962 Sino-Indian War, Nathu La witnessed skirmishes between soldiers of the two countries. Shortly thereafter, the passage was sealed and remained closed for more than four decades. [49]

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, China exerted pressure on India diplomatically and militarily.[12] In September 1965, China reinforced Yatung and nearby mountain passes with another infantry regiment.[50] India also had a build-up in this area.[51] On the south-eastern front of Sikkim the four passes of Nathu La, Jelep La, Cho La and Dongju had 9, 37, 1 and 9 Indian positions respectively.[52] This build-up was influenced by the region's proximity to East Pakistan,[51] and the tensions that remained following the 1962 war.[53] Following Chinese pressure, Indian troops at Nathu La and Jelep La received orders to withdraw.[52] Nathu La was under Major General Sagat Singh and he refused to withdraw.[52] As a result, in the coming few days, Jelep La was occupied by the Chinese while Nathu La remained defended under India.[54]

The coming months saw both sides tussle over dominance in Chumbi Valley.[55] Numerous Indian incursions were reported by Chinese sources.[56] At Nathu La, differing perceptions of the Line of Actual Control among frontline troops on both sides factored in to the increasing tensions.[56] Trench digging, laying of barbed wires, patrolling, celebrating Independence Day, every action became contentious.[57] Between 7 and 13 September 1967, China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) and the Indian Army had a number of border clashes at Nathu La and Cho La, including the exchange of heavy artillery fire.[58][59] Numerous casualties were reported on both sides.[60]

In 1975, following a referendum, Sikkim acceded to India and Nathu La became part of Indian territory.[61] China, however, refused to acknowledge the accession,[62] but the two armies continued to maintain informal communication at the border despite the freeze in diplomatic relations.[63] In 1988 the visit of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to China marked the beginning of fresh talks between the two countries.[64]

2006 re-opening

In 2003, with the thawing of Sino-Indian relations, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee's visit to China led to the resumption of talks on opening the border.[65] The border agreements signed in 2003 were pursuant to the "Memorandum on the Resumption of Border Trade" signed in December 1991, and "Protocol on Entry and Exit Procedures for Border Trade" signed in July 1992. The 2003 "Memorandum on Expanding Border Trade" made applicable and expanded the provisions of the 1991 and 1992 agreements to Nathu La.[66][67]

In August 2003, the Chief Minister of Sikkim Pawan Chamling shook hands with a PLA soldier along the border and followed it up by giving his wristwatch. The PLA soldier in return gave the Chief Minister a packet of cigarettes. This signaled the return of trade to Nathu La.[68] The formal opening was postponed a number of times between mid-2004 to mid-2006.[69][70] Finally, after remaining sealed for decades, Nathu La was officially opened on 6 July 2006,[71] becoming one of the three open trading border posts between China and India at the time, the other two being Shipki La and Lipulekh pass.[72] The reopening, which was a part of a number of political moves by China and India with regard to the formal recognition of Tibet and Sikkim as part of either country respectively,[73][74] coincided with the birthday of the reigning Dalai Lama.[74]

The opening of the pass was marked by a ceremony on the Indian side that was attended by officials from both countries. A delegation of 100 traders from each side crossed the border to respective trading towns. Despite heavy rain and chilly winds, the ceremony was marked by the attendance of many officials, locals, and international and local media.[71][44] The barbed wire fence between India and China was replaced by a 10 m (30 ft) wide stone-walled passageway.[1] 2006 was also marked as the year of Sino-Indian friendship.[75] It has been postulated that the reasons for opening the pass on both sides included economic and strategic ones, including that of stabilizing the borderlands.[44]

The narrative surrounding the reopening of the pass highlighted border trade, the ancient Silk Road,[76] and the ancient linkages between the two "civilisations".[77] Anthropologist Tina Harris explains that this state-based narrative diverged from the regional narrative.[77] While silk had been one of the commodities traded, this region saw a much larger trade of wool.[77] A trader told Harris that the route should have been called the "wool route".[78] Harris explains that this narrative of Nathu La rather highlighted the "contemporary global discourse"—that of a globalising and inter-connected Asia finding its place in the world, of which Sikkim and Chumbi Valley were a part.[79]

Post 2006

.jpg.webp)

Nathu La is one of the five officially agreed Border Personnel Meeting (BPM) points between the Indian Army and the People's Liberation Army of China for regular consultations and interactions between the two armies.[80] During the 2008 Tibetan unrest, hundreds of Tibetans in India marched to and protested at Nathu La.[81][82] In 2009, Narendra Modi, as the Chief Minister of Gujarat, visited the pass.[83] In 2010, the Queen's Baton Relay for the Commonwealth Games that year also stopped at main trade gate at the pass.[84] In 2015, Nathu La opened for tourists and pilgrims going to Kailash Mansarovar.[85]

Amidst the 2017 China–India border standoff centered around Doklam, the pilgrimage via Nathu La was cancelled.[86] The border tensions also affected trade through the pass.[87] The standoff officially ended at the end of August 2017;[88] and in October India's Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made a goodwill visit to Nathu La, also briefly interacting with Chinese soldiers at the pass.[89] In 2018, a "Special Border Personnel meeting" took place at the pass to mark the foundation day of the PLA.[88] On Yoga Day in 2019, Chinese soldiers and civilians participated in joint yoga exercises at Nathu La.[90]

In 2019 road conditions impacted movement across the pass.[91] In April 2020, following the coronavirus pandemic, the Sikkim government closed the pass.[92] The Kailash-Mansarovar pilgrimage through Nathu La would also remain shut.[92] Further, fresh political and border tensions and skirmishes in 2020 also affected trade.[91] This coronavirus pandemic–border tension situation continued into 2021, impacting movement across the pass.[93]

Flora and fauna

In 1910 Scottish botanist W. W. Smith visited the area. Vegetation he listed included species of Caltha scaposa, Cochlearia, Potentilla, Saussurea, Rhododendron, Cassiope, Primula, Corydalis, Arenaria, Saxifraga, Chrysosplenium, Pimpinella, Cyananthus, Campanula, Androsace, Eritrichium, Lagotis and Salvia.[94] Rhododendrons nobile and marmots have been seen on the ascent of the pass.[95]

Because of the steep elevation increase around the pass, the vegetation graduates from sub-tropical forest at its base, to a temperate region, to a wet and dry alpine climate, and finally to cold tundra desert devoid of vegetation. Around Nathu La and the Tibetan side, the region has little vegetation besides scattered shrubs. Major species found in the region include dwarf rhododendrons (Rhododendron anthopogon, R. setosum) and junipers. The meadows include the genera Poa, Meconopsis, Pedicularis, Primula, and Aconitum. The region has a four-month growing season during which grasses, sedges, and medicinal herbs grow abundantly and support a host of insects, wild and domestic herbivores, larks, and finches.[96] The nearby Kyongnosla Alpine Sanctuary has rare, endangered ground orchida and rhododendrons interspersed among tall junipers and silver firs.[97]

There are no permanent human settlements in the region, though it has a large number of defence personnel who man the borders on both sides. A small number of nomadic Tibetan graziers or Dokpas herd yak, sheep and pashmina-type goats in the region. There has been intense grazing pressure due to domestic and wild herbivores on the land. Yaks are found in these parts, and in many hamlets they serve as beasts of burden.[96] The region around Nathu La contains many endangered species, including Tibetan gazelle, snow leopard, Tibetan wolf, Tibetan snowcock, lammergeier, raven, golden eagle, and ruddy shelduck. Feral dogs are considered a major hazard in this region. The presence of landmines in the area causes casualties among yak, nayan, kiang, and Tibetan wolf.[96]

The avifauna consists of various types of laughing thrushes, which live in shrubs and on the forest floor. The blue whistling-thrush, redstarts, and forktails are found near waterfalls and hill-streams. The mixed hunting species present in the region include warblers, tit-babblers, treecreepers, white-eyes, wrens, and rose finches. Raptors such as black eagle, black-winged kite and kestrels; and pheasants such as monals and blood pheasant are also found.[96]

Economy

Trade

Up until 1962, before the pass was sealed, goods such as pens, watches, cereals, cotton cloth, edible oils, soaps, building materials, and dismantled scooters and four-wheelers were exported to Tibet through the pass on mule-back. Two hundred mules, each carrying about 80 kilograms (180 lb) of load, were used to ferry goods from Gangtok to Lhasa, which used to take 20–25 days. Upon return, silk, raw wool, musk pods, medicinal plants, country liquor, precious stones, gold, and silverware were imported into India.[99] Most of the trade in those days was carried out by the Marwari community, which owned 95% of the 200 authorised firms.[74]

The Nathu La Trade Study Group (NTSG) was set up by the state government of Sikkim in 2003 to study the scope of border trade in Sikkim with specific focus on Nathu La, which was scheduled to reopen.[100] The informal group, consisting of civil servants and trade experts, was headed by Mahendra P. Lama and submitted its report in 2005.[101][102] The report laid down two projections, a "higher projection", and a "lower projection".[103] The lower projection estimated border trade through Nathu La at ₹353 crore (US$44 million) by 2010, ₹450 crore (US$56 million) by 2015 and ₹574 crore (US$72 million) by 2020.[103] The higher projection estimated border trade through Nathu La ₹12,203 crore (US$1.5 billion) by 2015.[103] India's Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) gave an even higher estimation that trade could cross USD 10 billion in a decade.[104][101]

These figures were also based upon policy recommendations in the paper. While the trade may not have met the study group's estimate, which 15 years later seem "over ambitious", it has benefitted the impacted areas positively.[105] Ancillary benefits were also highlighted by the report such as revenue for truckers even with low volumes of vehicle movement.[106] Since July 2006, trading is open Mondays through Thursdays.[71] In 2006 India exempted 29 items for export and 15 items for import from duty. In 2012, 12 more items were added to the list.[107][108] Apart from illegal items, China did not put any restrictions on the border trade in 2006.[109]

- Agriculture Implements

- Blankets

- Copper Products

- Clothes

- Cycles

- Coffee

- Tea

- Barley

- Rice

- Flour

- Dry Fruits

- Dry and Fresh Vegetables

- Vegetable Oil

- Gur and Misri

- Tobacco

- Snuff

- Cigarettes

- Canned Food

- Agro Chemical

- Local Herbs

- Dyes

- Spices

- Watches

- Shoes

- Kerosene

- Stationary

- Utensil

- Wheat

- Textiles

2012

- Processed Food Items

- Flowers

- Fruit and Spices

- Religious Products

- Readymade Garment

- Handicraft and Handloom Products

- Local Herbal Medicine

- Goat Skin

- Sheep Skin

- Wool

- Raw Silk

- Yak Tails

- China Clay

- Borax

- Yak Hair

- Szaibelyita

- Butter

- Goat Cashmere (Pasham)

- Common Salt

- Horses

- Goats

- Sheep

2012

- Readymade Garments

- Shoes

- Carpets

- Quilt/Blankets

- Local Herbal Medicine

| Years | NTSG Projection (₹ crore) | Actual Trade (₹ crore) | Percentage fulfilled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low projections | |||

| 2006–2010 | 353 | 6.54 | 1.85% |

| 2006–2015 | 450 | 114.60 | 25.46% |

| High projections | |||

| 2006–2010 | 2266 | 6.54 | 0.29% |

| 2006–2015 | 12203 | 114.60 | 0.93% |

| Sources: NTSG report 2005; Department of Commerce and Industries (Sikkim) 2016[110] | |||

The reopening of the pass was expected to stimulate the economy of the region and bolster Indo-Chinese trade, however the result has been underwhelming.[109] In 2008, Mahendra P. Lama commented upon the mismatch in projections and actual trade during the first two years, "this is mostly attributed to poor road conditions, nascent infrastructural facilities, limited tradable items and lukewarm attitude of the policy-makers."[111] Road limitations also constricted the size and number of trucks that can use the route.[112] Further, there is a large mismatch between Indian and Chinese thinking with regard to trade through Sikkim, and a large mismatch with regard to on-the-ground infrastructure development with regard to supporting trade through Nathu La.[113] In 2010 and 2011 there were no imports from China via the pass according to Government of Sikkim data.[114] Weather also restricts trade to about 7 to 8 months and roughly between May and November.[115]

There were concerns among some traders in India that Indian goods would find a limited outlet in Tibet, while China would have access to a ready market in Sikkim and West Bengal.[116] A concern of the Indian government is also the trafficking of wildlife products such as tiger and leopard skins and bones, bear gall bladders, otter pelts, and shahtoosh wool into India. The Indian government has undertaken a program to sensitise the police and other law enforcement agencies in the area.[117]

Tourism

Nathu La is part of the tourist circuit in eastern Sikkim.[118] On the Indian side, only citizens of India can visit the pass on Thursdays to Sundays, after obtaining permits one day in advance in Gangtok.[119][120] There is no 'no man's land' at the pass. Minimal military presence and barbed wire separates both sides. Tourists informally shake hands and take photographs with the Chinese soldiers and army office in the background.[121] Only meters apart, soldiers at Nathu La are among the closest soldiers along the entire Sino-India border.[122] Domestic tourism at the pass was opened up in 1999.[123]

- Tourist locations on the Indian side

Stairs leading to the Indian side of the border.

Stairs leading to the Indian side of the border. "Pass of Listening Ears"

"Pass of Listening Ears" A visual from the stairs. The Natula memorial visible at right center.

A visual from the stairs. The Natula memorial visible at right center. The Natula memorial.

The Natula memorial. The main trade road connecting both sides.

The main trade road connecting both sides. The Chinese army office taken from the Indian Army office at the pass.

The Chinese army office taken from the Indian Army office at the pass.

The pass provides an alternative pilgrimage route to Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar.[124] The route through Nathu La, as compared to the original route through Lipulekh pass, requires pilgrims to make a much easier and shorter trek.[125][126] However, with new road construction by the Border Roads Organisation, the Lipulekh pass route has also been made easier.[127] Baba Harbhajan Singh memorial and shrine is also part of the Nathu La tourist circuit.[128]

Mail exchange

Twice a week at 8:30 am in an exchanging lasting only 3 minutes, on Thursdays and Sundays, the international surface mail between India and China is exchanged by postmen of the respective countries at Nathu La's Sherathang border post. While the volume of mail is declining due the advent of email and internet, it is mostly from the Tibetan Refugees in India or among the locals with relatives on both sides of the border. This arrangement reduces the mail delivery time for the people of border areas to few days which would otherwise takes weeks to be delivered via the circuitous logistics chain. In this short exchange, no words is spoken as both sides do not understand each other's language, mail is exchanged, an acknowledgement letter is signed, sometimes empty mail bags are exchanged due to dwindling mail volume. This system, since the times of chogyals, continues uninterrupted even during the India-China disputes at 14,000 altitude where temperature drops to −20 °C (−4 °F).[129] An agreement between China and India in 1992 gave official recognition to the process.[130][129]

Transport

The Gangtok–Nathu La road was first made motorable in 1958.[46][47] At the time it only existed to Sherathang after which the journey was on foot. China had not developed the road during those years.[46]

The stretch has several sinking zones and parts are prone to landslides.[131] The flow of vehicles is regulated and road maintenance is supported by the Border Roads Organisation, a wing of the Indian Army.[132] The road has an average rise of 165 feet (50 m) per km over a stretch of 52 kilometres (32 mi).[132] Around 2006, plans were made to widen the road.[76] Double-laning commenced in 2008.[133] Also known as the JN Marg,[119] and later known as National Highway (NH) 310, an alternative axis was constructed in 2020.[134] 2006 also marked the inauguration of a railroad from Beijing to Lhasa via the Qinghai–Tibet line. In 2011, the railroad began to be extended to Shigatse.[76] There has been talk of extending the Qinghai-Tibet Railway to Yadong.[135][136] China National Highway 318 (Shanghai to Zhangmu) is connected to Chumbi Valley from Shigatse via provincial road S204, about 30 km from Nathu La and Jelep La.[137]

India has been planning an extension of rail services from Sevoke in West Bengal's Darjeeling district to Sikkim's capital Gangtok, 38 miles (61 km) from Nathu La.[138] The intention to construct this sometime in the future was confirmed in March, 2023, by the Minister of Railways Ashwini Vaishnaw.[139] However, so far, the actual broad gauge line construction has been limited to a 45 km extension from Sevoke to Rangpo, due for completion in 2022.[140]

Notes

- ↑ Alternative spellings and variations include Nathu-la,[4] Nathula,[5] Natu La,[6] Natö-la, Natöla,[7] Natoi La,[8] Nathui La,[9] Gnatui,[10] as well as its Tibetan transcription Rnathos La.[11] and a Chinese transliteration Natuila.[12]

- ↑ Other elevations mentioned include 14,140 feet (4,310 m),[2] and 14,790 feet (4,510 m).[20]

References

- 1 2 Hong'e, Mo (6 July 2006). "China, India raise national flags at border pass to restart business". China View. Xinhua. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- 1 2 "Node: Nathu La (3179568394)". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ ENVIS Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim (2006), p. 32.

- ↑ Harris 2013, p. ix.

- ↑ Gokhale, Nitin A. (3 October 2003). "Hallelujah, Nathula!". Outlook India.

- ↑ India, Sikkim, United States, Central Intelligence Agency, 1981.

- ↑ Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (2009), One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, Brill, p. 643, ISBN 978-90-04-17732-1

- ↑ Sessional papers. Inventory control record 1, Volume 67, Great Britain, Parliament, House of Commons, 1904, p. 28: "Yatung is situated about eight miles from the Jeylap-la in the valley of the Yatung Chhu at its junction with the Chamdi Chhu which runs down from Natoi-la."

- ↑ Smith 1913, pp. 325–327.

- ↑ Edgar 1874, pp. 53, 57, 121.

- ↑ "Opening of new pilgrimage route in Tibet by China makes it easier for Indian pilgrims" (PDF), Jiefang Daily, 29 October 2015 – via India in the Chinese Media (niasindiainchina.in)

- 1 2 Balazs 2021, p. 149.

- ↑ Economic under performance

- ↑ O'Brien, Derek (2011). "India. Major Passes". The Puffin Factfinder. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-878-8.

- ↑ Pradhan, Keshav (6 July 2006). "In the good ol' days of Nathu-la". The Times of India, Mumbai. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. p. 10.

Today the 85-year-old Nima recalls how he and his companions literally dragged the mules over the pass - which means listening ears - singing to keep their spirits high.

- 1 2 Arora 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ "Chinese Embassy Publishes Tibet Advertorial in Indian Media". in.chineseembassy.org (中华人民共和国驻印度共和国大使馆; Embassy of the People's Republic of China in India ). 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

In Tibetan language, Nathula means a place where the "snow is deepest and the wind strongest".

- ↑ Bajpai 1999, p. 183-184.

- 1 2 Waddell, L. Austin (1905), Lhasa and its Mysteries, London: John Murray, p. 106 – via archive.org: "For this, the Nathu Pass (14,250 feet), a goat-track, 10 miles to the north of the Jelep and over the same ridge, was opened out by Mr White."

- 1 2 ENVIS Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim (2006), p. 43.

- ↑ Saha, Sambit (8 September 2003). "Trading post: Prospects of Nathu-La". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ↑ Nathu La to Yatung, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Markham, Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle (1876), p. civ.

- ↑ Brown, Percy (1934), Townsend, Joan (ed.), Tours in Sikhim and the Darjeeling District (Revised ed.), Calcutta: W. Newman & Co, p. 144 – via archive.org

- ↑ Hasija 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Arora 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Edgar 1874, p. 32: "There was scarce a day during my stay in East Sikkim that I did not meet people either coming from, or on their way to, Darjeeling with goods, the value of which at first sight seemed quite disproportioned to the labour that had to be undergone in taking them to market."

- ↑ Edgar 1874, p. 32.

- ↑ Arora 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Edgar 1874, p. 78.

- ↑ Powers, John; Holzinger, Lutz (2004). History As Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles Versus the People's Republic of China. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7.

- 1 2 Landon 1905, p. 38.

- ↑ Landon 1905, p. 34.

- ↑ Chapman 1940, p. 4, Introduction by Sir Charles Bell.

- ↑ "British Photography in Central Tibet 1920–1950". The Tibet Album. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- 1 2 Chapman 1940, p. 22, Chapter Two: To Phari.

- ↑ Chapman 1940, pp. 9–10, Chapter One: Preparations.

- 1 2 3 4 Chapman 1940, p. 23, Chapter Two: To Phari.

- ↑ "1936–1937 Lhasa Mission Diary. Champithang Bungalow. 13,350 ft, 23 mile march". tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk (The Tibet Album, British Photography in Central Tibet 1920–1950). 1 August 1936. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ Schulz, Matthias (10 April 2017). "German Nazi belief in a lost civilisation lead to one of the most bizarre expeditions in history". Australian Financial Review.

- ↑ Balikci-Denjongpa, Anna. "German Akay (1915–2005)" (PDF). Bulletin of Tibetology, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Engelhardt, Isrun (2007). "Tibet in 1938–39: The Ernst Schäfer Expedition to Tibet". Serinda Publications. Retrieved 29 October 2021 – via info-buddhism.com.

- ↑ Arpi, Claude (6 July 2006). "Nathu La: 'Sweetness and light'". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jha, Prashant (August 2006). "A break in the ridgeline". Himal Southasian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Boquérat, Gilles (2007). "Sino-Indian Relations in Retrospect". Strategic Studies. 27 (2): 18–37. ISSN 1029-0990. JSTOR 45242394 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mehta, Jagat S (2002). "Catalysing Graduated Modernisation Through Diplomacy: Nehru's Visit to Bhutan 1958". World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues. 6 (2): 89, 90. ISSN 0971-8052. JSTOR 45064894 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 "Lok Sabha Debates. Seventh Session (Second Lok Sabha)" (PDF). Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi. 8 April 1959. p. 25. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Ray, Sunanda K Datta (10 July 2006). "Nathu La: It's more than revival of a trade route". Phayul.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- 1 2 Abdenur 2016, p. 30.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, pp. 149–150.

- 1 2 Balazs 2021, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Balazs 2021, p. 151.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, p. 148.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, p. 154.

- 1 2 Balazs 2021, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Sreedhar (1998). "China Becoming A Superpower and India's Options". Across the Himalayan Gap: An Indian Quest for Understanding China (Ed. Tan Chung). Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, pp. 156–159.

- ↑ Balazs 2021, p. 159.

- ↑ Abdenur 2016, p. 29.

- ↑ Abdenur 2016, p. 31.

- ↑ Gokhale, Vijay (2021). The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India. Penguin Random House India. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-93-5492-121-6.

- ↑ "India-China Political Relations". Embassy of India, Beijing. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ↑ Malik, Mohan (October 2004). "India–China Relations: Giants Stir, Cooperate and Compete" (PDF). Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. pp. 3–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021 – via Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC).

- ↑ Hsu 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ "Documents signed between India and China during Prime Minister Vajpayee's visit to China". www.mea.gov.in (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India). 23 June 2003. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Rai, Tina (6–12 August 2003). "The first exchange over Nathula" (PDF). Digital Himalaya project, University of Cambridge. Sikkim Matters Now. p. 4. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ↑ Hsu 2005, pp. 10, 13, 18.

- ↑ "India, China to reopen Silk Route in October". Hindustan Times. PTI, IANS. 11 September 2005.

- 1 2 3 "Historic India–China link opens". BBC News. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ↑ "Nathula reopens for trade after 44 years". Zee News. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ↑ Hsu 2005, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 3 Pradhan, Keshav (6 July 2006). "Trading Heights". The Times of India. p. 10. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ↑ "Activities planned for India–China Friendship Year – 2006". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. 23 January 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- 1 2 3 Harris 2013, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Harris 2013, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Harris 2013, p. 90.

- ↑ Harris 2013, p. 92.

- ↑ "Indian soldiers prevent Chinese troops from constructing road in Arunachal". The Times of India. 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Stratton, Allegra (24 March 2008). "Tibet protesters disrupt Olympic flame ceremony". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Three hundred Tibetans begin march to China-India border". Radio Free Asia. 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "Modi celebrates Diwali with jawans at Nathu La pass". The Times of India. 17 October 2009.

- ↑ Kundu, Amalendu (18 July 2010). "Queen's Baton lost and found". The Times of India.

- ↑ Basheer, K. P. M. (16 June 2015). "After half-a-century, Nathu La Pass opens for Kailash-Manasarovar pilgrims on Thursday". The Hindu Business Line.

- ↑ "Kailash Mansarovar Yatra through Nathu La pass cancelled as India-China border standoff continues". Scroll.in. 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Gurung, Wini Fred (18 July 2017). "Doklam standoff affecting trade through Nathu La". Observer Research Foundation.

- 1 2 "Indian, Chinese armies meet at Nathu La on 91st anniversary of PLA foundation". Hindustan Times. PTI. 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Varma, K. J. M. (9 October 2017). "Nirmala Sitharaman's visit to Nathu La strikes a chord with Chinese media". Livemint.

- ↑ "Chinese armymen, civilians do yoga with Indian defence personnel along India-China border". The Times of India. PTI. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- 1 2 Singh, Shiv Sahay (12 September 2020). "India–China standoff casts shadow on Nathu La border trade". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- 1 2 Giri, Pramod (23 April 2020). "Covid-19: Sikkim closes Nathu La trade route with China, suspends Kailash Yatra". Hindustan Times.

- ↑ Sharma, Ashwani (3 September 2021). "Indo-China Bilateral Trade From Shipki La Called Off For Two Consecutive Years". Outlook India.

- ↑ Smith 1913, p. 326, 350, 355, 359, 370, 375, 389, 390, 394, 398, 405, 406.

- ↑ Buchanan, W. J. (1916). Notes on Tours in Darjeeling and Sikkim (with Map). Darjeeling Improvement Fund. p. 13 – via PAHAR. Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 ENVIS Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim (2006), p. 44.

- ↑ ENVIS Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim (2006), p. 114.

- ↑ Lama 2016, p. 51.

- ↑ Roy, Ambar Singh (25 November 2003). "Nathula 'Pass'port to better trade prospects with China". Hindu Business Line. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ↑ Subba 2013, p. 1-2.

- 1 2 Mazumdar, Jaideep (3 October 2005). "Last Lap To Lhasa". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021.

- ↑ Das, Pushpita (4 July 2006). "Nathu La: Pass To Prosperity But Also A Challenge". Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Lama 2008, p. 111.

- ↑ Hsu 2005, p. 15.

- ↑ Chettri 2018, p. 18-20.

- ↑ Gupta, Gargi (1 July 2006). "The dragons of Nathula". Business Standard India. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- 1 2 Chettri 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India (23 August 2006). "Trade Between India And China Through Nathu La Pass". Press Information Bureau: Press releases. NIC. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007.

- 1 2 "Nathu La Pass on Sino-Indian border closes". China Daily. 15 October 2006. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ↑ Chettri 2018, p. 20.

- ↑ Lama 2008, p. 112.

- ↑ Lama 2008, p. 113-114.

- ↑ Lama 2008, p. 115-116.

- ↑ Lama 2016, p. 50-51.

- ↑ Bhutia 2021, India-China Border Trade at Nathu La.

- ↑ "Nathu-la shows the way: It opens a new route to amity". The Tribune. 8 August 2006. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ Perappadan, Bindu Shajan (23 June 2006). "Doubts over traffickers using re-opened Nathula Pass". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ↑ Harris 2013, p. 100.

- 1 2 Hasija 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ ENVIS Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim (2006), p. 45.

- ↑ Hasija 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Singh, Sushant (13 September 2017). "50 years before Doklam, there was Nathu La: Recalling a very different standoff". The Indian Express. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ Pramanik, Probir (11 September 1999). "Travel industry's new hotspot in icy belt: Nathula". Rediff. UNI. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ Vinayak, G (28 July 2004). "Nathu La: closed for review". The Rediff Special. Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ↑ Mathur, Nandita (23 June 2015). "The shorter route to Kailash Mansarover". Livemint. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ↑ Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (22 February 2018). "Kailash Mansarovar Yatra through both Nathu La, Lipulekh Pass routes opened after Sino-Indian understanding". The Economic Times. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ↑ "New road will shorten Kailash Mansarovar yatra by six days". The Economic Times. IANS. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ↑ Hasija 2012, p. 4.

- 1 2 Pramanik, Probir (16 April 2017). "You've got mail, at 14,000 ft: Sikkim man delivers letters between lndia, China". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Pramanik, Probir (20 March 2021). "Mailman builds bridge over border". The Telegraph India. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑

Kaur, Naunidhi (2 August 2003). "A route of hope". Volume 20 – Issue 16. Frontline Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 Dutta, Sujan (20 November 2006). "Nathu-la wider road reply to Beijing". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ "BRO undertakes double laning of Gangtok-Nathula road". Outlook India. 7 May 2008.

- ↑ "Gangtok-Nathu La route alternate alignment commissioned". Sikkim Express. 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "China to build three railways in Tibet". China Daily. 29 June 2006. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ↑ Arpi, Claude (14 June 2017). "The Tibet-India Railway". Indian Defence Review.

- ↑ Surana, Praggya (2018). Nagal, Lt Gen Balraj (ed.). "Manekshaw Paper 70: China Shaping Tibet for Strategic Leverage" (PDF). New Delhi: Centre for Land Warfare Studies. p. 16.

- ↑ "North Bengal-Sikkim Railway Link". Railway Technology. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ "Vande Bharat train will run in Sikkim's Rangpo by next year". news9live.com. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ↑ Hazarika, Myithili (8 August 2020). "Sikkim could finally be added to India's rail map by 2022, 13 years after project began". ThePrint.

Bibliography

- Edgar, John Ware (1874), Report on a visit to Sikhim and the Thibetan frontier in October, November, and December, 1873, Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press – via Internet Archive

- Landon, Perceval (1905). The Opening of Tibet: An Account of Lhasa and the Country and People of Central Tibet and of the Progress of the Mission Sent There by the English Government in the Year 1903-4. Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Smith, W. W. (1913), Records of the Botanical Survey of India. Vol 6. No 7. The Alpine and Sub-Alpine Vegetation of South-East Sikkim., Superintendent Government Printing, India – via PAHAR. Internet Archive

- Chapman, F. Spencer (1940) [1938]. Lhasa: The Holy City. Readers Union Ltd. Chatto & Windus. – via Internet Archive.

- Bajpai, G. S. (1999). China's Shadow Over Sikkim: The Politics of Intimidation. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-1-897829-52-3.

- Carrington, Michael (2003). "Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves: The Looting of Monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet". Modern Asian Studies. 37 (1): 81–109. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03001033. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 3876552. S2CID 144922428 – via JSTOR.

- Hsu, Kuei Hsiang (2005), The Impact of Opening up Sikkim's Nathu-La on China-India Eastern Border Trade, Taipei City, Taiwan: Conference paper presented at the 527th MTAC Commissioner Meeting.

- Ecodestination of India. Sikkim Chapter. (PDF), Environmental Information System Centre on Eco-Tourism, Sikkim., 4 June 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2007

- Lama, Mahendra P. (24 May 2008), "Connectivity Issues in India's Neighbourhood" (PDF), India-China Border Trade Connectivity: Economic and Strategic Implications and India's Response, India International Centre, New Delhi.: Asian Institute of Transport Development, New Delhi., pp. 93–126

- Hasija, Namrata (1 April 2012). "Nathu La: Amidst the "Listening Ears" (A Trip Report)" (PDF). Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2021.

- Subba, Bhim B (January 2013). "India, China and the Nathu La: Realizing the Potential of a Border Trade". Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi.

- Harris, Tina (2013). Geographical Diversions: Tibetan Trade, Global Transactions. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4573-4.

- Arora, Vibha (2008). "Routing the Commodities of the Empire through Sikkim (1817-1906)" (PDF). Commodities of Empire Working Paper. No. 9. Open University. ISSN 1756-0098. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- — Arora, Vibha (2013), "Routeing the Commodities of the Empire through Sikkim (1817–1906)", in Jonathan Curry-Machado (ed.), Global Histories, Imperial Commodities, Local Interactions, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 15–37, doi:10.1057/9781137283603_2, ISBN 978-1-349-44898-2

- L. H. M. Ling; Adriana Erthal Abdenur; Payal Banerjee; Nimmi Kurian; Mahendra P. Lama; Bo Li (2016). India China: Rethinking Borders and Security. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-13006-1.

- — Abdenur, Adriana Erthal (2016), "Trans-Himalayas: From the Silk Road to World War II", Rethinking Borders and Security, University of Michigan Press, pp. 20–38, doi:10.3998/mpub.6577564, ISBN 978-0-472-13006-1, JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.6577564 – via JSTOR

- — Lama, Mahendra P. (2016), "Borders as Opportunities: Changing Matrices in Northeast India and Southwest China", Rethinking Borders and Security, University of Michigan Press, pp. 39–59, doi:10.3998/mpub.6577564, ISBN 978-0-472-13006-1, JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.6577564 – via JSTOR

- Chettri, Pramesh (21 June 2018). "India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments". HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies. 38 (1). ISSN 2471-3716.

- Bhutia, Dechen (2021). "9: Reviving Border Trade and Tourism along Nathu La in Sikkim". In Srikanth, H.; Majumdar, Munmun (eds.). Linking India and Eastern Neighbours: Development in the Northeast and Borderlands. SAGE Publishing India. ISBN 978-93-91370-78-7. LCCN 2021941443 – via Google Books.

- Balazs, Daniel (February 2021). Wars, fought and unfought: China and the Sino-Indian border dispute (Thesis). S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. doi:10.32657/10356/150314. hdl:10356/150314.

Further reading

Books

- Report on the Engineer Operations of the Tibet Mission Escort 1903–04. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent, Government Printing, India. 1905 – via PAHAR. Internet Archive.

- Minney, R. J. (1920). Midst Himalayan Mists. Calcutta; London.: Butterworth and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- Easton, John (1929). An unfrequented highway through Sikkim and Tibet to Chumolaori. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-81-206-1268-6.

- Macdonald, David (1930), Touring in Sikkim and Tibet, Self-published (1930), Thacker, Spink & Co. (1943) and Asian Educational Services (1999), ISBN 978-81-206-1350-8

- Notes, Memoranda And Letters – India-China White Paper Vol 1–14. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. 1959 – via PAHAR. Internet Archive.

- Moraes, Dom (1960). Gone away, an Indian journal. London: Heinemann – via Internet Archive.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar; Bhattacharya, Rakhee; Bandyopadhyay, Kausik, eds. (2009). Sikkim's tryst with Nathu La: What awaits India's East and Northeast? (PDF). Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies. Anshah Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8364-050-3.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Cognoscenti Books. ISBN 978-1-300-46486-0.

- Harris, Tina (2017). "6: The Mobile and the Material in the Himalayan Borderlands". In Saxer, Martin; Zhang, Juan (eds.). The Art of Neighbouring. Making Relations Across China's Borders (PDF). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 145–166. doi:10.5117/9789462982581 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISBN 978-94-6298-258-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Fatma, Eram (2017). IndiaChina Border Trade: A Case Study of Sikkim's Nathu La. KW Publishers Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-86288-64-6.

Journals

- Lunt, James (1968). "The Nathu La". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 113 (652): 331–334. doi:10.1080/03071846809424869. ISSN 0035-9289.

- Jacob, Jabin T. (2007). "The Qinghai–Tibet Railway and Nathu La – Challenge and Opportunity for India". China Report. 43 (1): 83–87. doi:10.1177/000944550604300106. ISSN 0009-4455. S2CID 154791778.

- Harris, Tina (2008). "Silk Roads and Wool Routes: Contemporary Geographies of Trade Between Lhasa and Kalimpong". India Review. 7 (3): 200–222. doi:10.1080/14736480802261541. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 154522986.

- Datta, Karubaki (2014). "Tibet trade through the Chumbi Valley – growth, rupture and reopening". Vidyasagar University Journal of History 2013–2014. 2.

Think tanks

- Mohanty, Satyajit (2008), "Nathu La. Bridging the Himalayas." (PDF), IPCS Issue Brief 73, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi

- Ranade, Jayadeva (2012). "Nathu La & the Sino-Indian Trade: Understanding the Sensitivities in Sikkim". Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi – via JSTOR.

- Wangchuk, Pema (2013), "India, China and the Nathu La: Converting Symbolism into Reality" (PDF), IPCS Issue Brief 202, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi

- Pazo, Panu (2013), "India, China and the Nathu La: Securing Trade & Safeguarding the Eco System", IPCS Issue Brief 206, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi

- Singh, VK (Autumn 2014). "The Skirmish at Nathu La (1967)" (PDF). Scholar Warrior. Center For Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS): 142–149.

- Bhandari, R.K. (2 December 2014), "Urgent Need for Steps to Make Nathu La Route to Kailash Mansarovar Safe for Pilgrims", VIF India

News

- Huggler, Justin; Coonan, Clifford (20 June 2006). "China reopens a passage to India". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006.

- Madan, Tanvi (13 September 2017). "How the U.S. viewed the 1967 Sikkim skirmishes between India and China". Brookings Institution.

- "China's social media hails Nirmala Sitharaman's 'namaste' as its foreign ministry downplays gesture". Firstpost. 10 October 2017.

External links

The dictionary definition of Nathu La at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Nathu La at Wiktionary Quotations related to Nathula at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Nathula at Wikiquote Media related to Nathu La at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nathu La at Wikimedia Commons India, China reopen Nathu La pass at Wikinews

India, China reopen Nathu La pass at Wikinews