Muhammad ibn Sulayman ibn Ali | |

|---|---|

| Governor of Basra | |

| In office 759/60–764/5, 776/7–780/1, 783/4, 785/6 – 789 | |

| Governor of Kufa | |

| In office 764/5–772 | |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 789 |

| Spouse | Abbasa bint al-Mahdi |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Abbasid Caliphate |

| Battles/wars | Alid revolt of 762–763, Battle of Fakhkh |

Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbbās (Arabic: محمد بن سليمان بن علي بن عبد الله بن عباس; c. 740–789) was a member of the Abbasid dynasty who served as provincial governor of Kufa and Basra and its dependencies in the Persian Gulf for most of his life. He also played a leading role in the suppression of the pro-Alid uprisings of 762–763 and 786, and helped ensure the peaceful accession of Caliph al-Mahdi in 775. His enormous fortune was confiscated after his death by Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

Origin and character

Muhammad was a cousin of the first two Abbasid caliphs, Abu'l-Abbas al-Saffah and Abu Ja'far al-Mansur.[1] His father, Sulayman ibn Ali al-Hashimi, had long served as governor of Basra. Sulayman accumulated enormous estates in the area, which he turned into his virtual fiefdom, erecting a new governor's palace and engaging in various public works in the city. After his death in 759/60, that position was inherited by Muhammad and his brother Ja'far.[2] The historian Hugh N. Kennedy qualifies him as "the ablest and most important of the younger generation of the Abbasid family",[3] and he appears to have enjoyed the esteem of al-Mansur: the historian al-Tabari reports that when Muhammad's older brother Ja'far once complained of receiving a donation only half the size of his brother's, the Caliph replied that "Wherever we turn we find some trace of Muhammad in it and some part of his gifts in our house, whereas you do not do any of this".[4] As a close member of the dynasty, and moreover as someone who apparently never held any ambition towards the throne, he was one of the few outsiders allowed entry into the inner apartments of the caliphal palace.[5]

Career

Muhammad came to prominence during the rebellion of Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya in 762, where, despite his youth—he was in his early twenties—he played a major role in the Abbasid attempts to suppress the uprising.[6] Muhammad was at Basra at the time, and seized a number of Alid partisans who fled to the city and brought them before al-Mansur.[7] Soon after, Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya's brother Ibrahim rose in revolt in Basra as well. Muhammad ibn Sulayman and his brother Ja'far tried to suppress it by hastily gathering a force of some 600 of their own retainers, but failed. Expelled from Basra, they wrote to al-Mansur to inform him of events.[8] When the Abbasid forces under Isa ibn Musa confronted Ibrahim in January 763, Muhammad and Ja'far attacked the rebel forces from the rear, clinching the victory for the Abbasids.[9]

In the aftermath of the uprising's failure, he was appointed governor of Basra, replacing Salm ibn Qutayba in 763/4.[10] In the next year, he was appointed governor of Kufa, replacing Isa ibn Musa, who had just been demoted in the line of succession below al-Mansur's son al-Mahdi. Isa refused to acquiesce to his demotion, so Muhammad's appointment was a deliberate snub to him from the Caliph.[11] Muhammad is still recorded as governor of Kufa until 772, when he was replaced by Amr ibn Zuhayr al-Dabbi (although the 9th-century compiler Umar ibn Shabbah claims that he was dismissed in 770).[12]

In autumn 775, he was among the leading members of the dynasty who accompanied al-Mansur to the pilgrimage, where the caliph died on 7 October.[13] During the aftermath, he helped ensure the peaceful transition of power. Al-Tabari reports that when the oath of allegiance to al-Mahdi was taken to him by the army commanders, only one of them, Ali ibn Isa ibn Mahan, tried to demur, pointing out Isa ibn Musa's claims. Muhammad reportedly slapped him in the face and berated him, and even considered having him beheaded, until Ali relented and took the oath.[14] Muhammad was then sent with al-Abbas ibn Muhammad to administer the oath to the people of Mecca.[15] Muhammad also married al-Mahdi's daughter Abbasa.[16][17]

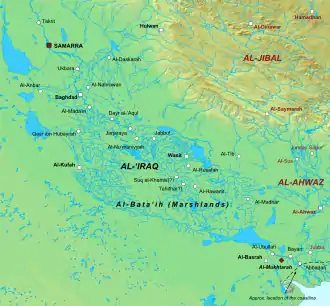

He is again recorded as governor of Basra from 776/7–780/1, as well as having authority over the dependent districts of the Tigris, Bahrayn, Oman, Ahwaz and Fars.[18] In 777/8, he undertook the expansion of the great mosque of Basra, on the orders of al-Mahdi.[19] According to al-Tabari, al-Mahdi in the same year also gave him the governorship of Sind, to which he appointed Abd al-Malik ibn Shihab al-Misma'i as his deputy.[20] He patronized the famous singer Ibrahim al-Mosuli, and jealously forbade him from leaving Basra, until one of al-Mahdi's visiting court eunuchs heard Ibrahim sing, and informed the Caliph of his talents.[21] Muhammad was dismissed in 780/1, apparently amidst accusations of embezzlement, for al-Mahdi sent his own secretary in charge of taxation to the city, and ordered the arrest and investigation of Muhammad's officials.[22] Muhammad was back at his post in Basra in 783/4.[23]

In 786, he participated in the pilgrimage along with other members of the dynasty, and by coincidence was thus involved in the suppression of the Alid rebellion led by Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya's nephew, Husayn. Taking his own armed retinue, he secured Mecca, and defeated the Alids and their partisans at the Battle of Fakhkh on 11 June.[24][25] He is again attested as governor of Basra and its dependencies (now including the Yamamah) from 785/6 on,[26] and was still in office when he died in mid-November 789.[1][27]

Inheriting effective control of a major trade entrepôt such as Basra, Muhammad became enormously wealthy.[28] At his death, his wealth, reportedly amounted to sixty million dirhams, was confiscated by Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[29] Muhammad also appears to have been a "great hoarder", who never threw anything away.[28] Al-Tabari reports that Harun's agents found a huge trove of possessions, from valuable gifts sent from the provinces he governed even to the various items of clothing he had worn during his life, down to the ink-stained clothes he had worn in Quran school. They also found vast quantities of balms and food, especially fish, all of which had spoilt and were unceremoniously dumped on the street outside Muhammad's palace at al-Mirbad, the commercial centre of the city.[28][30] The stink was such that the Basrans had to avoid the area for several days.[28][30] After his death and the loss of his fortune, his descendants lost their prominent position.[17]

References

- 1 2 McAuliffe 1995, p. 227 (note 1072).

- ↑ Kennedy 2016, pp. 69, 75.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 12 (note 29).

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 113.

- ↑ Kennedy 2006, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Kennedy 2016, p. 75.

- ↑ McAuliffe 1995, pp. 227, 229.

- ↑ McAuliffe 1995, pp. 271–272, 277, 279.

- ↑ McAuliffe 1995, p. 288.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 12.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, pp. 15, 38–39.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, pp. 50, 61, 63, 66, 68, 72–74.

- ↑ Kennedy 2016, p. 93.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 91.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, p. 23 (note 90).

- 1 2 Kennedy 2016, p. 76.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, pp. 187, 195, 216, 217.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 198.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 203.

- ↑ Kennedy 2006, p. 128.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Kennedy 1990, p. 239.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 23–26, 30.

- ↑ Kennedy 2016, p. 109.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 40, 100.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 Kennedy 2006, p. 142.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 Bosworth 1989, pp. 106–107.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXX: The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Mūsā al-Hādī and Hārūn al-Rashīd, A.D. 785–809/A.H. 169–192. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-564-4.

- Gordon, Matthew S.; Robinson, Chase F.; Rowson, Everett K.; et al., eds. (2018). The Works of Ibn Wadih al-Ya'qubi: An English Translation. Vol. 3. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Kennedy, Hugh, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIX: Al-Mansūr and al-Mahdī, A.D. 763–786/A.H. 146–169. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0142-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2006). When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306814808.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016) [1981]. The Early Abbasid Caliphate: A Political History. Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-66742-3.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen, ed. (1995). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVIII: The ʿAbbāsid Authority Affirmed: The Early Years of al-Mansūr, A.D. 753–763/A.H. 136–145. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1895-6.