Muchland is a medieval manor in Low Furness in the county of Cumbria in northern England. The manor was the seat of the Lords of Aldingham, and included at its peak the villages of Bardsea, Urswick, Scales, Stainton, Sunbrick, Baycliff, Gleaston, Aldingham, Dendron, Leece and Newbiggin. The area also features the historic remains of Gleaston Castle, Aldingham Castle, Gleaston Water Mill, the Druids' Temple at Birkrigg, plus many prehistoric remains around Urswick and Scales.

The Place

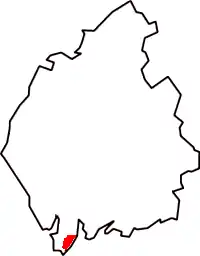

The area that became Muchland in the Middle Ages is situated on the eastern side of the Furness Peninsula in southwest Cumbria. On its eastern side, it is bounded for its entire length by the sands of Morecambe Bay, the shore of which has eroded considerably since the manor was created. Along the coast lie the villages, from north to south, of:

Muchland derives its name from Michael's Land after Michael le Fleming who was granted the lands by Henry I sometime between 1107 and 1111. These lands lay eastwards of Abbey Beck and southwards of the moors of Birkrigg and Swarthmoor and stretched right down to the southernmost tip of the peninsula at Rampside.[1] At that time the southern limit of the manor was Walney Channel, but it was later moved inland to follow the line of Sarah Beck or Roosebeck. This land became the new manor of Aldingham.

Aldingham is home to the Church of Saint Cuthbert, who was laid here after death on his journey to be buried. A little further down is the remains of Aldingham Moat and Aldingham Motte, both homes to the Lords of Aldingham in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Newbiggin was once home to Sea Mill, one of the three mills of the manor.

The western boundary of the manor is now the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness, which was originally land belonging to Stephen of Blois, but belonged to Furness Abbey from 1127 until 1536 when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries. There were numerous debates over the hunting rights between the Lords of Aldingham and the Abbots of Furness in places like Leece and Stainton, which lay at the western boundary of the manor. The small village of Dendron, also on the western boundary, is home to the seventeenth century Saint Matthew's Church where the artist George Romney went to school for a time.

Further east from Dendron is Gleaston, the geographical and administrative centre of the manor from the mid-thirteenth century. The village is dominated by Beacon Hill to the northeast, which legend says was used to signal danger to Piel Castle to the south, which can clearly be seen from the top of the hill. The village boasts the remains of Gleaston Castle and Gleaston Water Mill, the second corn mill of the manor. Gleaston Beck runs through the valley here from Urswick Tarn in the north to the coast at Newbiggin.

North of Gleaston are Scales and Little and Great Urswick. Little Urswick is now home to Low Furness Primary School, but was previously home to a seventeenth-century grammar school. Great Urswick, built around two sides of Urswick Tarn, boasts the ancient Church of Saint Mary and Saint Michael. It would seem this area was of considerable activity in the Iron Age.

To the east of Urswick is Birkrigg Common, so called because it was shared in common with the men of Urswick and Aldingham. This rocky hill has a number of archeological sites, including an ancient stone circle, and has views across Morecambe Bay, Furness and the mountains of the Lake District. On the edge of the common lies the small hamlet of Sunbrick, which is now little more than a few farms and houses, but shelters a small walled Quaker graveyard where leading Quaker Margaret Fell, who lived at nearby Swarthmoor Hall, is buried.

The northern boundary of the manor generally follows the line of the road leading from Lindal-in-Furness in the west to Conishead Priory on the coast. Beyond it is the market town of Ulverston and the manor of Pennington.

The Lost Villages of Muchland

It is known that several villages which once existed in Muchland have since disappeared off the map. Local legends are full of tales about villages on the coast being swept away by the encroaching tides, although there is little to substantiate the tales. It is certain that the gravelly coastline must have suffered considerable erosion over the past centuries and that any village too near the shore might have fallen victim to its advances. Aldingham, for example, may once have been up to a mile in length, stretching out into what is now Morecambe Bay with the church at its centre.

Besides those villages lost to the sea, several others have disappeared. Perhaps the most interesting is Hart, which is mentioned in the Domesday Book as Hert. There was later a mill named Hart Mill which is known to have been in the vicinity of Gleaston. Archeological investigations have taken place to discover the site of this early mill around the valley where Gleaston Water Mill now stands, but they have yielded little evidence. The name Hart was probably shortened from Hart Carrs, which means 'marsh of the harts'. To the south of Gleaston, at the end of Carrs Lane, there is a large flat area which has been drained, through which still flows Hart Carrs Beck. It is possible that the village once stood in this area.

Two other villages named in the Domesday Book have also disappeared, but are even more difficult to track down. Crivelton probably stood on the coast between Rampside and Roose but has since been washed away by the sea. The name is recorded as Clivertun in the Domesday Book, which suggests a location on a cliff. Fordbootle was probably situated somewhere around modern-day Stank, although its name suggests a location beside a watercourse, possibly further west on the River Yarl. Both Clivertun and Fordbootle were listed in the Domesday Book as vills or townships forming the Manor of Hougun held by Earl Tostig. Around 1153 Roose, Crivelton and Fordbootle were part of an exchange of land between Muchland and Furness Abbey, suggesting that it was certainly situated in that area.

A final village to be mentioned in the Domesday Book is Alia Lies, meaning 'another Leece'. The position of this lost village is by no means certain, but it may have been in the area of Old Holbeck, to the west of present-day Leece, or nearer the coast to the south of the village.

History

Before the Manor

The area later named Muchland has been inhabited since at least the Mesolithic period and evidence of Upper Paleolithic habitation has been found in caves at Scales. Remains of prehistoric settlements from the mesolithic to the Bronze Age have been found at Gleaston and Scales, including a bronze sword and axe head, and human bones. It is believed that a post-glacial lake near Gleaston would have provided food and resources for a small community from the end of the last ice age to the Bronze Age. There is a small stone circle on Birkrigg Common known locally as the Druids' Temple which revealed a Bronze Age burial urn during excavations [OL6 292741].

In the Iron Age, when the Carvetii and, later, Brigantes tribes inhabited the region, there was a great deal of activity on the rocky ground surrounding present-day Urswick and Scales. There are visible remains of a fort to the north of Great Urswick [OL6 274753], a settlement northwest of Little Urswick known as Urswick Stone Walls [OL6 260740] and a homestead to the east [OL6 275734] as well as numerous tumuli and burial chambers in the area.

The Romans may also have been present in Urswick during their occupation. Recent archeological investigations in the area may have uncovered the presence of a Roman fort (a claim which has been criticised by leading local archeologists) and it is believed that the parish church of St Mary and St Michael may contain remnants of a sub-Roman church which could have been the centre of a monastery, although all of these claims are yet to be substantiated by solid evidence. It is possible that the Romans exploited the rich iron-ore resources of the area, which had been utilised in previous times and provided the catalyst for a booming industrial economy in the area in the 19th century.

In the 4th century AD this part of England belonged to the kingdom of Coel Hen, known as Northern Britain or Kyle, but was later in a division of that kingdom known as Rheged. Little is known about the local history at this point, but it is known that the area would have remained Celtic until around the 8th century when Rheged was annexed to Northumbria and English Angles began to filter in. In 685AD land in south Cumbria was granted to Saint Cuthbert and it was recorded that the area still had a significant British population. Part of an early English cross bearing a runic inscription from around this period is available to view in Urswick church.

The English slowly displaced or assimilated the native Cumbric Celts, although they may have remained in pockets around the region (as is evidenced by place names such as Walney, meaning 'Isle of the British' from Old Norse walna+ey). In 925AD Norsemen began landing on the local shores from Norway via Ireland, Man and Scotland but they seem to have been peaceable farmers rather than vicious warriors and they settled amongst the English and British in the region, although part of a Norse sword was found in nearby Rampside. The Norse influence on the area was a significant one, shown not only by the large number of Norse place-names in the area, but also by the discovery of a 12th-century inscription at Loppergarth near Ulverston, which contained a curious mix of both Norse and English runes.

The Lords of Muchland

The le Flemings

After the Norman Conquest in 1066 the small manor of Aldingham was granted to Roger de Poitou as part of a much larger holding which included land across much of the north of England. At that time the area was on the very fringe of Norman England. When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086 Aldingham had been confiscated from de Poitou for his part in a plot against William I, but it was returned to him shortly after. By 1102 Aldingham had been confiscated from de Poitou once again, but before this he had built a ringwork near the coast at Aldingham.

Around 1107 Aldingham was granted to Michael le Fleming (Latinized to Flandrensis, "of Flanders") and it was he who gave his name to the manor, literally "Michael's Land". At this point the manor stretched from Walney Channel around Rampside and Roose north to Sunbrick and Great Urswick. It was Michael or one of his sons that erected the motte at Aldingham on the site of Roger de Poitou's ringwork [OL6 278698].

In 1153, the second Michael le Fleming agreed an exchange of land with Furness Abbey, giving up Roose, Fordbootle and Crivelton for Little Urswick and part of Foss, near Bootle in Cumberland, so that the Abbot could get greater access to his port at Piel.

By the early 13th century the wealth and importance of the manor had increased significantly and the Lord of the manor was granted the right to hold his own courts Leet and Baron. The manor of Bardsea was also added to the le Fleming estate. Around this time the seat of the manor of Muchland was moved from the motte at Aldingham to a nearby moated site [OL6 279700], probably due to the advance of the sea and the erosion of the hill on which the motte stands.

In 1227 the overlordship of Muchland was changed from the Duke of Lancaster to Furness Abbey. This seems to have been an unwelcome decision for the Lords of Aldingham, as the Abbot began claiming rights to lands within the bounds of Muchland. Over coming years, William le Fleming (alias de Furness) got into several disputes over hunting rights with his neighbour the Abbot of Furness which eventually resulted in William being exempt from formal attendance at the Abbots Court and the men of Muchland being banned from entering the Abbot's town of Dalton-in-Furness.

The de Haringtons

In the mid 13th century Michael de Furness - direct descendant of the first Lord of Aldingham - died crossing the Leven Sands in Morecambe Bay after dining at Cartmel Priory and the manor passed to the Cansfield family from Lancashire through Michael's sister Alina de Furness. It was probably Richard de Cansfield who initiated the move inland from Aldingham to Gleaston, where a wooden hall was probably built about 0.5 km north of the present village [OL6 262715]. When Alina and Richard's son William de Cansfield was drowned in the River Severn the manor passed again through a female heir to the de Harington family from north west Cumbria.

The son of that marriage, John de Harington (1281–1347) was knighted in 1306 and was created Baron Harington upon being summoned by writ to Parliament in 1326. It was he who was responsible for the building of Gleaston Castle on the site of the previous hall, which was begun before 1325 and finished around 1340. The 1st Baron seems to have been quite a contradictory character. Not only was he a member of Parliament, he sat on councils, was a Commissioner of array for eight years, sat on various commissions in the north of England, and completed his obligatory military service with Edward, Prince of Wales and Andrew de Harcla. But he was also involved in a faction opposed to Piers Gaveston and complied in his murder, for which he received a pardon in 1313 and was pardoned again in 1318. His activities with Andrew de Harcla in the Scottish Marches led to his being outlawed in 1323 on discovery of Harcla's treason, but he was pardoned upon surrender then awarded as custodian of the truce with Scotland.

During their time as lords of the manor of Muchland the de Harringtons increased their estate greatly through marriage to heiresses, gaining lands in Devon, Cornwall, Leicestershire, Ireland, and further lands in Cumberland and Westmorland. In 1460 the only male heir to the manor, William Bonville was killed at the age of 17 along with his father and grandfather at the Battle of Wakefield leaving behind a new born baby girl, Cecilia. She later married Thomas Grey, 1st Marquis of Dorset, who was grandfather to Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, who was father of Lady Jane Grey who became Queen of England but was beheaded after nine days by Queen Mary. And so the manor passed to the crown in whose hands it remained until it was given to the Cavendish family of Holker Hall in the 18th century who held it until 1926 when it was sold.

Genealogy

Descendants of Michael le Fleming. Lords of Aldingham are highlighted in bold.

Michael le Fleming, Lord of Aldingham

| (d.1150)

|

Michael le Fleming m. Christiana de Stainton

(d.1186) |

|

William de Furness m. Ada de Furnys Osulf of Flemingby

(c.1150-1203) | |

| |

Michael de Furness m. Agatha Fitz Henry Robert of Hafrinctuna

(1197-1219) | |

| |

William de Furness Thomas de Harrington

| |

|-----------------------------| |

Michael de Furness Alina m. Richard de Cantsfield Michael de Harrington

(d.1269 crossing Leven Sands) | |

|------------------------| |

William de Cantsfield Agnes m. Robert de Harrington

(drowned in R. Severn) (d.1293) | (d.1297)

|

Joan Dacre m. John de Harrington, First Baron of Aldingham

| (1281-1347)

|

Robert de Harrington

|(d.1334)

|

Joan de Birmingham m. John de Harrington

| (1328-1363)

|

Alice de Greystoke m1. Robert de Harrington m². Isobel Loring

| (1356–1406)

|----------------------------|

John de Harrington William de Harrington m. Margaret

(d.1418) (1390-1457) |

|

William Bonville m. Elizabeth

|

|

William Bonville m. Katherine Neville

(c.1443-1460) |

|

Cecile m. Thomas Grey

|

|

Thomas Grey

|

|

Henry Grey m. Lady Frances Brandon

|

|

Lady Jane Grey

Toponymy

Muchland was originally 'Michael's Land', which changed to 'Mickle Land' from the local version of Michael, which was confused with another local term from the Old Norse mikkel meaning 'great' and so became 'Much Land'

Adgarley means 'Eadgar's slope' from Old English Eadgars hlið

Aldingham means 'home of Alda's people or descendants' from the Old English Alda+inga+ham. [Domesday Aldingham]

Bardsea ?unsure. Possibly 'bard's resting place' from Celtic bard eisteddfa [Domesday Berretseige]

Baycliff ?unsure. There are no notable cliffs in the area, despite the village overlooking Morecambe Bay. [early form Belleclive, 1212]

Birkrigg Common 'ridge with birch trees' from Old Norse birkr hryggr

Bolton probably 'farmstead with a shelter' from Old Norse boðl tun, the Domesday Book records this as Bolton-le-Moors

Crivelton ?unsure. Domesday records this lost village as Clivertun, which probably means 'village on a cliff' from OE clif+ton. There may be an additional Old Norse element meaning 'hill', klif+haugr+tun

Dendron Probably clearing in a valley from Old English denu+rum. [Domesday Dene]

Fordbootle 'dwelling by a ford' from ford+boðl [Domesday fordebodele]

Gleaston means 'green hill farm' from Old Norse glas+haugr+tun. [Domesday Glassertun]

Goadsbarrow means 'Godi's or Gauti's burial mound' with the Old English beorg

Harbarrow There are several explanations. The second element is certainly 'hill' from Old English beorg. The first is probably 'hare' from Old English hara (there is a Hare Hill nearby), but may also be 'herd' from heord, 'oats' from Old Norse hafri, or 'grey' from Old English har.

Hart now lost, this probably just means 'hart' or 'stag' from Old Norse hjortr. It seems likely this is a shortening of the name Hart Carrs, which means 'marsh where harts live' with Old Norse kjarr. Hart Carrs Beck flows through an area of flat, often boggy land. [Domesday Hert]

Holbeck 'stream in a hole' from Old Norse hol-bekkr'

Leece means 'glades' from Old English leahs. [Domesday Lies]

Newbiggin means 'new building' with Old or Middle English biggin

Rampside either 'Hrafn's shieling' from Old Norse Hrafns saetr or 'ram's head' from Old English ramms heofod, referring to the shape of the coast

Roose 'moor' from the Brythonic Celtic ros

Scales means 'huts' from Old Norse skalis

Scarbarrow ?unsure. Possibly 'hill with huts' from Old Norse skali berg, but may also be 'hill with a scar' - there is a small stream which has eroded the hill into a steep gully.

Skeldon Moor possibly ridge or ledge from a local word skelf, or 'shell midden' with Old Norse skel dun and Old English mōr

Stainton means 'farm by stones' from Old Norse steinn+tun [Domesday Steintun]

Sunbrick means 'pig slope' from Old Norse svin+brekka [Domesday Suntun, meaning 'pig farm']

Urswick ?unsure. '-wick' could either be related to Latin vicus meaning 'town', which is a common feature of places along Roman roads (there's evidence of one to the north); or it could be from Old English wick meaning 'farm'

See also

References

- ↑ F Barnes, Barrow and District, 1968