Mordecai Aaron Günzburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | מֹרְדְּכַי אַהֲרֹן גִינְצְבּוּרְג |

| Born | 3 December 1795 Salant, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 November 1846 (aged 50) Vilna, Russian Empire |

| Pen name | Yonah ben Amitai |

| Language | Hebrew, Yiddish |

| Literary movement | Haskalah |

| Notable works | Devir (1844) Aviezer (1863) |

Mordecai Aaron Günzburg (Hebrew: מֹרְדְּכַי אַהֲרֹן גִינְצְבּוּרְג, romanized: Mordekhai Aharon Gintsburg; 3 December 1795 – 5 November 1846), also known by the acronym Remag (רמא״ג) and the pen name Yonah ben Amitai (יוֹנָה בֶּן־אֲמִתַּי), was a Lithuanian Jewish writer, translator, and educator. He was a leading member of the Haskalah in Vilna,[1][2] and is regarded as the "Father of Hebrew Prose."[3][4]

Biography

Günzburg was born into a prominent Jewish family in Salant (now Salantai, Lithuania) in 1795.[5] His father Yehuda Asher (1765–1823), under whom he studied Hebrew and Talmud, was one of the early members of the Haskalah in Russia,[6] and wrote treatises on mathematics and Hebrew grammar.[7] Günzburg was engaged at the age of twelve, and married two years later, whereupon he went to live with his in-laws at Shavly.[8] He continued his studies under his father-in-law until 1816.[9] From there Günzburg went to Polangen and Mitau, Courland, where he taught Hebrew and translated legal papers into German. He did not stay in Courland long, and after a period of wandering settled in Vilna in 1835.[10]

In 1841, he founded with Shlomo Salkind the first secular Jewish school in Lithuania, which he headed until his death in 1846 at the age of fifty-one.[7][10] A. B. Lebensohn, Wolf Tugendhold, and Michel Gordon,[11] among others, published eulogies in his memory.[6]

Work

Günzburg was best known for his series of histories of contemporary Europe.[12][13] His first major publication was Sefer gelot ha-aretz (1823), an adaption into Hebrew of Joachim Heinrich Campe's Die Entdeckung von Amerika,[14] a Yiddish translation of which he released the following year as Di entdekung fun Amerike.[6] In 1835, he published the first volume of his universal history Toldot bnei ha-adam, adapted from Karl Heinrich Ludwig Pölitz's Handbuch der weltgeschichte.[15] (A few chapters of the second volume would later be published in the Leket Amarim, a supplement to Ha-Melitz, in 1889.) In the same genre he wrote Ittote Russiya (1839), a history of Russia, and Ha-Tzarfatim be-Russiya (1842) and Pi ha-ḥerut (1844), accounts of the Napoleonic Wars.[16]

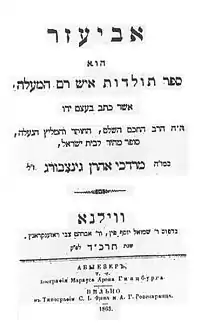

Among his other publications were Malakhut Filon ha-Yehudi (1836), an translation from German of Philo's embassy to Caligula, and the anthology Devir (1844), an eclectic collection of letters, tales, and sketches.[17] Many of Günzburg's works were published posthumously, most notably his autobiography Aviezer (1863, composed between 1828 and 1845),[18][12] as well as Ḥamat Dammeshek (1860), a history of the Damascus affair of 1840, and the satirical poem Tikkun Lavan ha-Arami (1864).[19][7]

Günzburg's outlook was influenced by Moses Mendelssohn's Phaedon and the Sefer ha-Berit of Phinehas Elijah ben Meïr.[13] He struggled energetically against Kabbalah and superstition as the sources of the Ḥasidic movement, but he was at the same time opposed to the free thought and proto-Reform movements.[20]

Selected publications

- Sefer gelot ha-aretz ha-ḥadashah al yede Kristof Kolumbus [Discovery of the New Land by Christopher Columbus] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Missionarrow. 1823. Later published as Masa Kolumbus, o, gelot ha-aretz ha-ḥadashah [Columbus' Voyage; or, Discovery of the New Land].

- Di entdekung fun Amerike [The Discovery of America] (in Yiddish). Vilna: Rom. 1824.

- Toldot bnei ha-adam [History of Mankind] (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Vilna: Defus Binyamin ben David Ari' Segal. 1832.

- Kiryat sefer [Republic of Letters] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Binyamin ben David Ari' Segal. 1835. hdl:2027/nnc1.cu58931899. A letter-writing manual.

- Malakhut Filon ha-Yehudi [Delegation of Philo Judaeus] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Avraham Yitsḥak bar Shalom. 1836.

- Ittote Russiya [Chronicles of Russia] (in Hebrew). Warsaw: Defus Menaḥem Man ve-Simḥah Zimel. 1839. A history of Russia.

- Ha-Tzarfatim be-Russiya [Frenchmen in Russia] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus M. Rom. 1842.

- Maggid emet [Herald of Truth] (in Hebrew). Leipzig: C. L. Fritzsche. 1843. A refutation of Max Lilienthal's Maggid Yeshu'ah.

- Devir [Inner Sanctum] (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Vilna: Defus Menaḥem Man ve-Simḥah Zimel. 1844. hdl:2027/nnc1.0026859629.

- Pi ha-ḥerut [Voices of Freedom] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Menaḥem Man ve-Simḥah Zimel. 1844.

- Sefer yemei ha-dor [Days of the Generation] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Yosef Reʼuven Rom. 1860. A history of Europe from 1770 to 1812.

- Ḥamat Dammeshek [The Wrath of Damascus] (in Hebrew). Königsberg. 1860. hdl:2027/njp.32101076527512.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Devir [Inner Sanctum] (in Hebrew). Vol. 2. Vilna: Defus Shmuel Yosef Finn ve-Avraham Tzvi Rosenkranz. 1861. hdl:2027/uc1.ax0001254127.

- Aviezer; hu sefer toldot ish ram ha-maʻalah asher katav be-etsem yado [Abiezer] (Autobiography) (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Shmuel Yosef Fin ve-Avrohom Tzvi Rozenkrantz. 1863.

- Tikkun Lavan ha-Arami: shir sipuri neged ha-ḥasidim [Righting Lavan the Aramæan] (in Hebrew). Vilna: Defus Halter ve-Eisenstadt. 1894 [1864].

- Ha-Moriyyah [Moriah] (in Hebrew). Warsaw: Druk fun Aleksander Ginz. 1878. hdl:2027/nnc1.cu58952225.

- Leil shimmurim [Watch-night] (in Hebrew). Warsaw: Defus Yosef Unterhendler. 1883.

References

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rosenthal, Herman; Seligsohn, M. (1904). "Günzburg, Mordecai Aaron ben Judah Asher". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 112–113.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rosenthal, Herman; Seligsohn, M. (1904). "Günzburg, Mordecai Aaron ben Judah Asher". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Abramson, Glenda M.; Rabin, Chaim; Leiter, Samuel. "Hebrew literature: Romanticism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Saul M. (1939). "Max Lilienthal's Activities in Russia; New Documents". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (35): 44–50. JSTOR 43058467.

- ↑ Rhine, Abraham Benedict (1910). Leon Gordon: An Appreciation. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. p. 37.

- ↑ Landman, Isaac, ed. (1969). "Günzberg, Mordecai Aaron". The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: KTAV Publishing House. p. 133.

- ↑ Raisin, Jacob S. (1913). The Haskalah Movement in Russia. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. pp. 213–221.

- 1 2 3 Kharlash, Yitskhok (13 August 2015). "Mortkhe-Aron Gintsburg (Mordechai Aharon Ginzburg, Güenzburg)". Yiddish Leksikon. Translated by Fogel, Joshua. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 Friedlander, Yehuda (2008). "Gintsburg, Mordekhai Aharon". In Hundert, Gershon (ed.). YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Translated by Hann, Rami. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Biale, David (1997). Eros and the Jews: From Biblical Israel to Contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 149, 155. doi:10.1525/9780520920064. ISBN 978-0-520-92006-4. S2CID 261466493.

- ↑ Galron-Goldschläger, Joseph, ed. (2019). "M. A. Güntzburg". Lexicon of Modern Hebrew Literature (in Hebrew). Ohio State University. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- 1 2 Ahimeir, Abba (2007). "Guenzburg, Mordecai Aaron". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ↑ Landman, Isaac, ed. (1943). "Gordon, Michel". The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 65.

- 1 2 Mintz, Alan (1979). "Guenzburg, Lilienblum, and the Shape of Haskalah Autobiography". AJS Review. 4: 71–110. doi:10.1017/S0364009400000428. JSTOR 1486300. S2CID 162554102.

- 1 2 Bartal, Israel (1990). "Mordechai Aaron Günzburg: A Lithuanian Maskil Faces Modernity". In Malino, Frances; Sorkin, David (eds.). From East and West: Jews in a Changing Europe, 1750–1870. Translated by Greenwood, N.; Schramm, L. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 126–147. ISBN 9780814327159.

- ↑ Shavit, Zohar (Spring 1992). "Literary Interference between German and Jewish-Hebrew Children's Literature during the Enlightenment: The Case of Campe". Poetics Today. 13 (1): 41–61. doi:10.2307/1772788. JSTOR 1772788.

- ↑ Greenbaum, Avraham (Spring 1993). "The Beginnings of Jewish Historiography in Russia". Jewish History. 7 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1007/BF01674497. JSTOR 20101146. S2CID 159491930.

- ↑ Waxman, Meyer. A History of Jewish Literature. Vol. 3. New York: Thomas Yoseloff. pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Banbaji, Amir (2012). "Two Paradigms of Aesthetics in Haskalah Literary Criticism: From Satanov to Lebensohn". Hebrew Studies. 53: 170–171. doi:10.1353/hbr.2012.0010. JSTOR 23344445. S2CID 170772448.

- ↑ Pelli, Moshe (May 1990). "The Literary Genre of the Autobiography in Hebrew Enlightenment Literature: Mordechai Ginzburg's 'Aviezer'". Modern Judaism. 10 (2): 159–169. doi:10.1093/mj/10.2.159. JSTOR 1396259.

- ↑ Slouschz, Nahum (1902). La Renaissance de la littérature hébraïque (1743–1885) (in French). Paris. pp. 88–89.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑

Rosenthal, Herman; Seligsohn, M. (1904). "Günzburg, Mordecai Aaron ben Judah Asher". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 112–113.

Rosenthal, Herman; Seligsohn, M. (1904). "Günzburg, Mordecai Aaron ben Judah Asher". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 112–113.