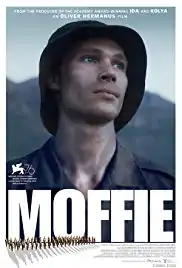

| Moffie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Oliver Hermanus |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Moffie by Andre Carl van der Merwe |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Jamie Ramsay |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Braam du Toit |

Production company | Portobello Productions |

Release date |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $28,704[2] |

Moffie is a 2019 biographical war romantic drama film co-written and directed by Oliver Hermanus. Based on the autobiographical novel of the same name by André Carl van der Merwe, the film depicts mandatory conscription into the notorious South African Defence Force (SADF) during apartheid through the eyes of a young closeted character Nicholas van der Swart (Kai Luke Brümmer) as he attempts to hide his attraction to another gay recruit (Ryan de Villiers) in a hostile environment.[3] The title derives from a homophobic slur in South Africa used to police masculinity.[4][5]

The film had its world premiere release at the Venice International Film Festival on 4 September 2019.[6] It also had its special screenings at other film festivals and received a number of accolades in various categories.[7] Its original 2020 theatrical release was disrupted. Distributed by Curzon Cinemas in the UK and IFC Films in the US, it was made available to stream and released in select theatres in 2021.[8]

Synopsis

The film begins in 1981, with South Africa's white minority government embroiled in a brutal proxy conflict in Angola and Namibia. A shy teenager, Nicholas van der Swart, like all white South African males over 16, is forced to undergo two years of compulsory military service in the SADF. He keeps his head down whilst the sadistic sergeants brutalise and train the recruits to hate and kill, policing their every move. The threat of shame, abuse, and worse looms over any who fail to conform to an ideal of Afrikaner hypermasculinity. There are details that set Nicholas apart: that, despite his Afrikaans surname from his stepfather, he is English-speaking; and as he finds quiet solidarity in and connection with another recruit Dylan Stassen, that he is gay, the latter of which is a punishable crime and could land him in the ominous Ward 22 if he were found out.[6][9]

Cast

- Kai Luke Brümmer as Nicholas van der Swart

- Matt Ashwell as young Nicholas

- Ryan de Villiers as Dylan Stassen

- Matthew Vey as Michael Sachs

- Stefan Vermaak as Oscar Fourie

- Hilton Pelser as Sergeant Brand

- Wynand Ferreira as Niels Snyman

- Hendrick Nieuwoudt as Roos

- Nicholas van Jaarsveldt as Robert Fields

Production

The film is based on the 2006 novel of the same name by André Carl van der Merwe, which the author based on his own diary entries from his time in the SADF. It tells the story of Nicholas discovering his sexuality in a dangerous context, and the irony and trauma of being forced to defend a regime that oppresses him and an ideology he does not agree with.

Eric Abraham and Jack Sidey bought the rights and approached Oliver Hermanus with the adaptation. Hermanus, whose family were affected by Apartheid, was initially skeptical of the white focus of the film, but found the memoir eye-opening and saw its potential to challenge. A few drafts later, he got to work on the script himself, widening the scope to examine the hate politics and toxic white masculinity that Apartheid tried to indoctrinate into a generation of men, both agents and property of the state, using Nicholas as a point of view. Sidey and Hermanus were able to take liberties with the source material and narrative structure.[5][10]

Jaci Cheriman hosted a nationwide casting call over the course of a year, scouting from professional agencies to local schools and drama clubs.[11] The cast underwent bootcamp training with a military adviser.[12] The crew worked with actors to develop the characters, incorporating stories from real-life veterans.[13]

The film was shot in academy ratio and colour graded to resemble the photography of the time.[14] Principal photography took place in early 2019 across the Western Cape. The crew scouted period-appropriate sites. Filming locations included Saron, Hopefield, and Grabouw. The ending scene was filmed on Windmill Beach in Simon's Town. As it took time to procure 80s train cars, the train scenes were filmed last in the Overberg between Caledon and Elgin.[15]

Reception

On Rotten Tomatoes, 90% of 94 critic reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.5/10. The website's critic consensus reads: "Moffie uses one South African soldier's story to grapple against a series of thorny questions – with rough yet rewarding results."[16]

The film was nominated for the Best Film category at the London Film Festival 2019. It received two nominations at the 2019 Venice Film Festival, for the Queer Lion Award and Venice Horizons Award.[17]

The Hollywood Reporter ranked the film to be among the best of 2021 so far as to early July 2021.[18]

Accolades

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Venice International Film Festival | Horizons Award | Moffie | Nominated | |

| Queer Lion | Nominated | [17] | |||

| BFI London Film Festival | Best Film | Nominated | |||

| Thessaloniki Film Festival | Mermaid Award | Oliver Hermanus | Won | ||

| British Independent Film Awards | Best Director | Nominated | |||

| Breakthrough Producer | Jack Sidey, Eric Abraham | Nominated | |||

| Best Cinematography | Jamie D. Ramsay | Nominated | [19] | ||

| 2020 | Tromsø International Film Festival | Aurora Prize | Moffie | Nominated | |

| Dublin International Film Festival | Jury Prize | Moffie | Won | [20] | |

| Molodist Kyiv Film Festival | Best LGBTQ Film | Moffie, Oliver Hermanus | Nominated | [21] | |

| FEST New Directors New Films Festival | Best Film | Moffie | Nominated | ||

| Guadalajara International Film Festival | Best Feature Film | Moffie | Nominated | ||

| 2021 | International Cinephile Society Awards | Best Adapted Screenplay | Oliver Hermanus, Jack Sidey | Nominated | [22] |

| British Academy Film Awards | Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director, or Producer | Jack Sidey | Nominated | [23] | |

Adaptations

Moffie was also imagined as a dance work in 2012 by Standard Bank Young Artist Award recipient Bailey Snyman. Snyman's version premiered at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 2012 to critical and acclaimed reception.[24][25] The dance version was also performed at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg in August 2012 and at the State Theatre in Pretoria in December 2012.[26] The work was revived for performances at the Artscape Theatre in Cape Town in January 2015.[27]

References

- ↑ "'Moffie': First Trailer for Venice Buzz Title About Homosexuality in Apartheid South Africa, 'Ida' Producer Among Team". Deadline Hollywood. 4 September 2019.

- ↑ "Moffie (2021)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ↑ Brooks, Xan (4 September 2019). "Moffie review – soldiers on the frontline of homophobia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ↑ de Waal, Shaun (1995). "Etymological note: On 'moffie'". In Gevisser, Mark; Cameron, Edwin (eds.). Defiant Desire: Gay and Lesbian Lives in South Africa. Routledge. p. xiii. ISBN 0-415-91060-9.

- 1 2 Sulcas, Roslyn (7 April 2021). "From a South African Slur to a Scathing Drama About Toxic Masculinity". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- 1 2 Vourlias, Christopher (5 October 2019). "Venice Drama 'Moffie' Explores Homophobia in South Africa". Variety. Variety Media. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ "Eye-opening film 'Moffie' is set to strut its stuff at Venice Film Festival". TimesLIVE. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ↑ Tartaglione, Nancy (10 April 2021). "'Moffie': New Trailer For BAFTA-Nominated Queer Drama Set In Apartheid South Africa; IFC Releases April 9 In U.S." Deadline. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ Romney, Jonathan (5 October 2019). "'Moffie': Venice Review". Screen Daily. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ Walters, Ben (16 April 2020). "Oliver Hermanus on Moffie: "Apartheid created a very binary code"". BFI. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ↑ "Oliver Hermanus' new film "Moffie" invited to premiere at Venice International Film Festival". NFVF. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ "'It was always about making you feel unsafe': Oliver Hermanus on Moffie". Seventh Row. 14 April 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ Roxborough, Scott (9 April 2021). "'Moffie' Director Oliver Hermanus on the Toxic Masculinity of Apartheid". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ↑ Shaffer, Marshall (9 April 2021). "Interview: Oliver Hermanus on Moffie and the Making of Men in South Africa". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ Handcore, Pratik (9 April 2021). "Where Was Moffie Filmed?". The Cinemaholic. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ↑ "Moffie (2019)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Oliver Hermanus' film 'Moffie' nominated for Queer Lion Award at Venice International Film Festival". Channel. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ↑ D.R. (4 July 2021). "The Hollywood Reporter Critics Pick the Best Films of 2021 (So Far)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ↑ "Moffie". BIFA. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Award Winners at VMDIFF20". DIFF Festival Limited.

- ↑ "150 films: International film festival "Molodist" announced the program". 8 August 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains Wins Top Prize at 18th ICS Awards". ICS Film. 20 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "2021 EE British Academy Film Awards: The Winners". BAFTA. 9 March 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ Kehe, Jason (9 August 2012). "How 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' Ended Up at a South African Arts Festival". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ↑ Flockemann, Miki; Cornelius, Jerome; Phillips, Jolyn (1 July 2012). "Grahamstown 2012: theatres of belonging, longing and counting the bullets". South African Theatre Journal. 26 (2): 218–226. doi:10.1080/10137548.2012.838335. ISSN 1013-7548. S2CID 147004600.

- ↑ "Dance Umbrella on the move". www.iol.co.za. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ↑ "Dance play revisits SA's dark recent past at Artscape Theatre". The Next 48hOURS. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

External links

- Moffie at IMDb

- Moffie at Metacritic