| Mingo Oak | |

|---|---|

The Mingo Oak, photographed in the 1930s | |

Mingo Oak | |

| Species | White oak (Quercus alba) |

| Coordinates | 37°49′7″N 82°3′42″W / 37.81861°N 82.06167°W |

| Date seeded | Estimated between 1354 and 1361 AD |

| Date felled | September 23, 1938 |

| Custodian | Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust Island Creek Coal Company North East Lumber Company West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission |

The Mingo Oak (also known as the Mingo White Oak) was a white oak (Quercus alba) in the U.S. state of West Virginia. First recognized for its age and size in 1931, the Mingo Oak was the oldest and largest living white oak tree in the world until its death in 1938.

The Mingo Oak stood in Mingo County, West Virginia, in a cove at the base of Trace Mountain near the headwaters of the Trace Fork of Pigeon Creek, a tributary stream of Tug Fork. The tree reached a height of over 200 feet (61 m), and its trunk was 145 feet (44 m) in height. Its crown measured 130 feet (40 m) in diameter and 60 feet (18 m) in height. The tree's trunk measured 9 feet 10 inches (3.00 m) in diameter and the circumference of its base measured 30 feet 9 inches (9.37 m). Assessments of its potential board lumber ranged from 15,000 feet (4,600 m) to 40,000 feet (12,000 m). Following the tree's felling in 1938, it was estimated to weigh approximately 5,400 long tons (5,500 t).

While the tree had long been known about for its size, the unique status of the Mingo Oak was not recognized until 1931, when John Keadle and Leonard Bradshaw of Williamson took measurements of the tree, and found it to be the largest living white oak in the world. Various estimates place the Mingo Oak's seeding between 1354 and 1361 AD. Using borings from the tree, the Smithsonian Institution determined that the Mingo Oak was the oldest tree of its species. The Island Creek Coal Company, the North East Lumber Company, and the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust leased 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) encompassing the tree to the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission for it to be managed as a state park for the life of the tree. The commission cleared the surrounding land and made improvements such as seating and picnic accommodations for visitors.

By the spring of 1938, the Mingo Oak failed to produce leaves, and on May of that year, West Virginia state forester D. B. Griffin announced the tree's death. The prevailing theory is that the tree died from the release of poisonous gases and sulfur fumes from a burning spoil tip in nearby Trace Gap. The tree was felled with fanfare on September 23, 1938, with transections being sent to the Smithsonian Institution and the West Virginia State Museum. Under the terms of the Island Creek Coal Company's lease with the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission, the land's lease around the former tree reverted to the company following the tree's felling.

Geography and setting

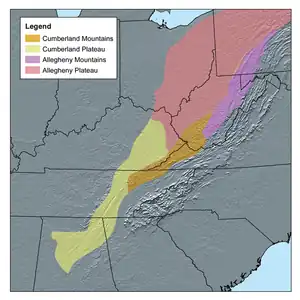

Prior to the arrival of European American settlers and explorers, the Allegheny Plateau region of West Virginia, lying to the west of the Allegheny and Cumberland mountain ranges of the Appalachian Mountains, was overlaid with old-growth forests consisting predominantly of deciduous mixed oaks and chestnut trees.[1] The cove forests of the Appalachian Mountains were undisturbed for approximately 300 million years, and the ample moisture and deep soils of cove topography allowed for the proliferation of temperate broadleaf and mixed forest species.[2]

The largest of the tree species in this virgin timbershed was the white oak (Quercus alba), which often exceeded 100 feet (30 m) in height and 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter.[1] While the white oak's range encompasses most of the Eastern United States, the most favorable environments for its growth are on the western slopes of the Appalachian Mountains.[3][4] According to botanist Earl Lemley Core, the species flourishes on northern mountain flanks, and in coves, which are small valleys or ravines between two ridge lines that are closed at one or both ends.[3] White oaks also thrive in moist lowlands and in upland topography, with the exception of extremely dry ridges with shallow soil.[3][4]

The Mingo Oak, known alternatively as the Mingo White Oak, was a white oak that stood in such a cove at the base of Trace Mountain on a shelf near the headwaters of the Trace Fork of Pigeon Creek, a tributary stream of Tug Fork.[5][6][7] The tree was located near the census-designated place of Holden, 10 miles (16 km) from Logan and 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Logan County line in Mingo County, from which it took its name.[6][8] The county was in turn named for the Mingo Iroquois peoples, of which Native American war leader Logan was affiliated.[9][10] Holden was the base of operations of the Island Creek Coal Company, which leased the land where the tree was located.[8]

Dimensions and age

The Mingo Oak was the largest specimen of these giant white oaks that dotted the old-growth forests of pre-settlement West Virginia.[1] The tree was found to be the largest living white oak in the United States, and in the world, following a survey of white oaks throughout the country. The Mingo Oak's nearest competition was a tree that was identified in Stony Brook on Long Island with a larger circumference, but a shorter height of 86 feet (26 m).[3][8]

Together with its uppermost branches, the tree reached a height of over 200 feet (61 m), and its trunk (or bole) towered to a height of 145 feet (44 m) where the trunk forked into branches that spread in all directions.[1][5][11] Its crown measured 130 feet (40 m) in diameter and 60 feet (18 m) in height.[5] The tree's trunk measured 9 feet 10 inches (3.00 m) in diameter.[1][5][11] The tree's circumference measured 30 feet 9 inches (9.37 m) at the base and 19 feet 9 inches (6.02 m) at 4.5 feet (1.4 m) from the ground.[8][12] As the virgin forest around it had been lumbered, the tree towered over the surrounding secondary forest.[8]

An initial estimate by lumbermen in 1931 stated that if the tree were to be cut for lumber, it would produce between 35,000 feet (11,000 m) and 40,000 feet (12,000 m) of board lumber, with a value of $1,400.[13] In February 1932, Perkins Coville of the United States Forest Service Department of Silvics estimated the tree's volume to contain 20,000 feet (6,100 m) of board lumber.[6] In 1938, engineers of the Island Creek Coal Company estimated that the tree's trunk contained 15,000 feet (4,600 m) of board lumber.[8] Following the tree's felling in 1938, it was estimated to weigh approximately 5,400 long tons (5,500 t).[14]

Various estimates place the tree's seeding sometime between 1354 and 1361 AD.[5][6][8] Using borings from the tree, the Smithsonian Institution determined that the Mingo Oak was the oldest tree of its species.[15] In September 1932, West Virginia state forester D. B. Griffin and Emmett Keadle, president of the Mingo County Fish and Game Protective Association in Williamson, used an increment borer to estimate the tree as having begun its growth around 1356, with a margin of error within 25 or 30 years.[8][16] Blueprints and boring samples were given to the West Virginia State Museum in Charleston and to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.[16]

Preservation attempts

Ownership of the timber land around the tree was eventually acquired by the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust, which leased the timbering rights to the North East Lumber Company. Under the lease agreement, the North East Lumber Company only paid for the lumber that it cleared from the land. The company found the Mingo Oak too large to cut down, and assessed that its removal was too costly to undertake.[8] The Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust also leased out the land where the tree was located to the Island Creek Coal Company for mining.[17]

The land around the tree continued to be developed. A highway connecting Logan to Williamson, was built parallel to the Trace Fork of Pigeon Creek, opposite the Mingo Oak. While the tree had long been known for its size, the unique status of the Mingo Oak was not recognized until 1931, when John Keadle and Leonard Bradshaw of Williamson took measurements of the tree, and found it to be the largest living white oak in the world.[16] Upon this finding by the two men, Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust and the Island Creek Coal Company agreed to make a joint deed conveying the property to the state of West Virginia. In late 1931, Emmett Keadle of the West Virginia Oil and Grease Company wrote a letter to Governor William G. Conley informing him of the tree's significance and the companies' willingness to lease the land to the state. Governor Conley responded to Keadle and suggested the companies convey the property to the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission.[17]

The Island Creek Coal Company, the North East Lumber Company, and the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust leased to the commission 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) encompassing the tree for it to be managed as a state park for the lifetime of the tree.[8][13][16] The commission removed vegetation from the immediate land around the tree, constructed a fence around the plot, and built a bridge crossing the Trace Fork of Pigeon Creek so that motorists could access the park from the highway.[8] The state built cooking ovens, picnic tables, and benches along the tree's southern slopes.[12][16] Also, due to its enormous size and advanced age, the Mingo Oak acquired spiritual and inspirational significance. It became a place of worship, and a pulpit and benches were built beneath its branches. During the summer months, outdoor sermons were delivered by preachers at the tree. The Mingo Oak was also credited with raising awareness of conservation.[5]

The Mingo Oak became a popular attraction for visitors. Conferences, such as the annual conference of the West Virginia Parent-Teacher Association in 1933, included visits to the tree as part of their itineraries.[18][19]

Death

In the summer of 1937, the Mingo Oak scarcely sprouted leaves on only a couple of its branches.[12][20] In February 1938, biologist Earl M. Vanscoy wrote in Castanea that the tree was "almost dead" due to the release of poisonous gases and sulfur fumes from a coal spoil tip of the Island Creek Coal Company, which had been burning nearby in Trace Gap.[5][7][21] In the spring of 1938, the tree failed to produce any leaves.[8][15][20] White oaks flower in the spring at approximately the same time as their leaves form, between late March and late May.[4] On May 4, 1938, West Virginia's state forester, D. B. Griffin, announced that the Mingo Oak was dead.[6][15] Griffin also noted that a fungus that only lived on dead or dying trees had been present on the tree for several months prior to its death.[15] The prevailing theory is that the tree died as a result of suffocation from the fumes of the burning pile of coal waste;[5][7][21] however, local media initially reported that the tree was killed as a result of fungal growth.[8]

Felling

In preparation for the tree's felling, some preliminary cutting was undertaken in the tree's north side in the afternoon hours of September 22. This work was done in order to manipulate the course of the tree's fall, and to estimate the length of time it would take to cut through the remainder of the trunk. After a saw had been worked approximately 2 feet (0.61 m) into the trunk, it was discovered that the tree was decomposing and open in its center. The lumber crews trimmed the tree's initial cut, and the further work to topple the tree was adjourned until the following morning.[12]

The tree was felled on September 23 during a ceremony attended by between 2,500 and 3,000 people.[5][8][20] Among those in attendance were state forester D. B. Griffin, the president of the Island Creek Coal Company, E. P. Rice, and representatives from other companies that had previously owned and leased the land where the tree was located.[5][8][12] In addition to standard cameras photographing the event, two movie cameras were brought to capture the felling and its associated events. Uniformed West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission officers, Mingo County sheriffs' deputies, and other law enforcement personnel were also on hand to provide security and direct traffic.[12]

Two lumberman were brought in to facilitate the cutting and toppling of the tree: Paul Criss of Charleston and Ed Meek of Indianapolis.[12][22] Criss brought with him a team of woodchoppers and sawyers representing the Kelly Ax and Tool Works Company.[12][14] Criss was a public relations spokesperson for the Kelly Ax and Tool Works Company.[14] Meek arrived with his own crew from the E. C. Atkins and Company, a saw manufacturer. Griffin also enlisted the assistance of a crew of game wardens and rangers. A nearby Civilian Conservation Corps camp also provided a team to assist in the felling and dismemberment of the tree. The E. C. Atkins and Company also brought a 9-foot (2.7 m) saw. Most of the readily available crosscut saws measured 6 feet (1.8 m) in length, thus rendering them ineffective at cutting through the tree's wide trunk, which measured over 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter 3 feet (0.91 m) from the ground.[12]

Prior to the tree's cutting, Criss shaved Meek's face with his axe. He lathered Meek's face and neck and moved his axe blade over Meek's bristles, drawing blood at his chin line. Criss commented: "That's the trouble with having a lot of officials around. I've shaved a thousand men with that axe and that's the first time I ever drew blood. These officials get me a little nervous."[12]

By 09:00, hundreds of people had arrived to observe the tree's toppling. At 10:00, the final cutting commenced. Criss decided to topple the tree downhill onto a ledge, which narrowed between the two ravines that emptied into Trace Fork. While it was assessed that the shelf was not long enough for the tree to land on, it was agreed upon by all the participants that given the rotten nature of the tree's top section, it would fracture notwithstanding the orientation of its fall. Prior to Criss cutting further into the tree, he assured the crews: "I can put her anywhere you want her gentlemen. Lay a $10 bill anywhere you like and I'll guarantee the trunk will cover it."[12]

The cutting of the tree began when the 9-foot (2.7 m) saw, operated by six men, was positioned across the trunk. The saw penetrated the trunk, and the adjacent area was cleared of bystanders. The spectators were repositioned up the hillside to the south and across the ravine to land that had previously been cleared by the Civilian Conservation Corps camp. The men moved the saw backward and forward, as woodchoppers widened the open wedge. After approximately 30 minutes, Criss yelled, "We're through boys."[12] The men removed the saw, and the woodchoppers continued to pick at the open wedge. The tree made a crackling sound, its upper limbs dipped, and the Mingo Oak crashed onto its designated felling location.[12] While it had been intended that the tree be down by 10:30, it was not until 11:00 that this occurred.[20] To assist in the segmentation of the collapsed tree, competitions were held in woodchopping and log sawing. Saw manufacturer E. C. Atkins and Company furnished saws for the competitors.[8]

Because of the tree's advanced decomposition within the center of its base, the trunk's lowest 24 feet (7.3 m) were assessed to be worthless; however, 66 feet (20 m) of the trunk was salvaged in one entire piece. Another cutting yielded a 40-foot (12 m) log in length, that averaged 54 inches (140 cm) in diameter. The Island Creek Coal Company sent the 66-foot (20 m) log to the Meadow River Lumber Company plant in Rainelle, which had the largest cutoff saw in the Eastern United States. From this log, transections were cut, and other divisions of it produced lumber, tabletops, and novelty items.[12] Various segments of the tree were cut and given to the West Virginia State Museum and the Smithsonian Institution.[5][20]

Legacy

The Mingo Oak was the largest living white oak;[3][7][23] and with the exception of the state's box huckleberries (Gaylussacia brachycera), it was the oldest living flora specimen in West Virginia.[3][5][7] The tree was referred to as the "mighty monarch of the mountains".[5] Biologist Earl M. Vanscoy said that the tree was "perhaps West Virginia's most remarkable tree";[7] and Colby B. Rucker of the Native Tree Society referred to the Mingo Oak as an "exceptional forest giant".[24]

Under the terms of the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission's lease from the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust, the North East Lumber Company, and the Island Creek Coal Company, the lease for the land around the former tree reverted to the Island Creek Coal Company following the tree's death and felling.[8]

In 1940, a club of whittlers presented a gavel made from a piece of the Mingo Oak to federal judge Harry E. Atkins in Huntington. Several of the club's whittlers had served as members of the jury during Atkins's court proceedings, and they presented the gavel as a token of their appreciation.[25]

The West Virginia Division of Culture and History installed a historic marker as part of the West Virginia Highway Historical Marker Program near the site of the Mingo Oak; it has since gone missing.[26] The marker read:

The largest white oak in the United States when it died and was cut down, 9-23-1938. Age was estimated to be 582 years. Height, 146 feet; circumference, 30 feet, 9 inches; diameter, 9 feet, 9 1/2 inches. Trunk contained 15,000 feet B. M. lumber.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Abramson & Haskell 2006, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Core 1971, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Rogers, Robert (1990). "Quercus alba". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 2. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015 – via Southern Research Station.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Talbott, Lowell (October 3, 1965). "Mingo Oak, State's Oldest 'Resident' Died in '38". Beckley Post-Herald and The Raleigh Register. Beckley, West Virginia. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Randall & Edgerton 1938, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vanscoy 1938, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 King, Henry (September 18, 1938). "Mingo County White Oak Will Be Felled Friday, Fungus Is Fatal To Forest Giant After 584 Years". Huntington Herald-Advertiser. Huntington, West Virginia. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ↑ West Virginia Legislature 2011, p. 828.

- ↑ "Mingo County: County Facts". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- 1 2 Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of West Virginia 1974, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Pinckard, H. R. (September 25, 1938). "They Cut Down The Great White Oak Of Mingo County". Huntington Herald-Advertiser. Huntington, West Virginia. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- 1 2 "Mingo White Oak Believed To Be Biggest In the World". Bluefield Daily Telegraph. Bluefield, West Virginia. August 30, 1931. p. 12. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Blizzard, William C. (December 11, 1966). "Sir Lancelot of the Ax". Sunday Gazette-Mail. Charleston, West Virginia. p. 5m. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "650-Year-Old Tree Is Dead". The New York Times. New York City. May 5, 1938. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mingo County Has Largest White Oak Tree in World: Giant Sentinel of Forest, More Than 500 Years Old, Is 145 Feet High". Charleston Daily Mail. Charleston, West Virginia. June 13, 1937. p. 29. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Mingo Oak: Correspondence Between Emmett Keadle and Governor William Conley Regarding the Mingo Oak". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ↑ "State P.-T. Session Takes Up Business". Charleston Daily Mail. Charleston, West Virginia. November 3, 1933. p. 22. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "State Parent-Teacher Conference Is Opened". Charleston Daily Mail. Charleston, West Virginia. November 2, 1933. p. 11. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chafin 2014, p. 102.

- 1 2 Clarkson 1964, p. 7.

- ↑ "Largest White Oak Tree to Be Cut Down". Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. September 23, 1938. p. 14. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ↑ Lamb 1939, p. 153.

- ↑ Rucker, Colby B. "Great Eastern Trees, Past and Present". Native Tree Society website. Native Tree Society. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Whittlers Give Judge Mingo Oak Gavel". The Cumberland News. Cumberland, Maryland. January 5, 1940. p. 17. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "West Virginia Highway Markers Database". West Virginia Archives and History; West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

Bibliography

- Abramson, Rudy; Haskell, Jean, eds. (2006). Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-456-4. OCLC 60669068.

- Chafin, Andrew (2014). Mingo County. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2097-5. OCLC 862781885. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Clarkson, Roy B. (1964). Tumult on the Mountains: Lumbering in West Virginia, 1770–1920. Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing Company. OCLC 2809295.

- Core, Earl L. (1971). "Silvical Characteristics of the Five Upland Oaks" (PDF). Oak Symposium Proceedings. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Upper Darby Township, Pennsylvania: United States Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture: 19–22. OCLC 5858126648. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Lamb, Frank H. (1939). Book of the Broadleaf Trees: The Story and the Economic, Social, and Cultural Contribution of the Temperate Broad-Leaved Trees and Forests of the World. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. OCLC 1457526. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Lewis, Ronald L. (1998). Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880–1920. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6297-1. OCLC 45727827. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Randall, Charles Edgar; Edgerton, Daisy Priscilla Smith (1938). Famous Trees. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture. OCLC 3185240. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Vanscoy, Earl M. (February 1938). "Some Famous West Virginia Trees". Castanea. Morgantown, West Virginia: Southern Appalachian Botanical Society. 3 (2): 14–18. ISSN 1938-4386. JSTOR 4031210. OCLC 57659851.

- West Virginia Legislature (2011). Darrell E. Holmes, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate (ed.). "West Virginia Blue Book, 2011". West Virginia Blue Book. Charleston, West Virginia: Chapman Printing. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

- Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of West Virginia (1974). West Virginia, a Guide to the Mountain State. New York City and St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Oxford University Press and Somerset Publishers. ISBN 978-0-403-02197-0. OCLC 595391. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016 – via Google Books.

External links

Media related to Mingo Oak at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mingo Oak at Wikimedia Commons- Image of the Mingo Oak at the West Virginia and Regional History Collection