Urang Minang or Urang Awak منڠكبو | |

|---|---|

A Minangkabau bride and groom. The bride is wearing a Suntiang crown. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 8 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6,462,713[2] | |

| | 4,281,439 |

| | 624,145 |

| | 345,403 |

| | 305,538 |

| | 202,203 |

| | 168,947 |

| | 156,770 |

| 1,000,000 (counted as part of the local "Malays")[3] | |

| 15,720 (counted as part of the local "Malays") | |

| 7,490 | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Minangkabau • Indonesian Also Other Malay varieties incl. Malaysian • Kerinci | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

a According to customary law ( Adat ), all Minangkabau people are Muslim | |

Minangkabau people (Minangkabau: Urang Minang or Urang Awak; Indonesian or Malay: Orang Minangkabau;[5] Jawi: منڠكبو), also known as Minang, are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the Minangkabau Highlands of West Sumatra, Indonesia. The Minangkabau's West Sumatera homelands was the seat of the Pagaruyung Kingdom,[6] believed by early historians to have been the cradle of the Malay race,[7] and the location of the Padri War (1821 to 1837).

Minangkabau are the ethnic majority in West Sumatra and Negeri Sembilan. Minangkabau are also a recognised minority in other parts of Indonesia as well as Malaysia, Singapore, and the Netherlands.

Etymology

There are several possible etymologies for the term Minangkabau (Minangkabau: Minang Jawi script: منڠ). While the word "kabau" undisputedly translates to "buffalo", the word "minang" is traditionally known as the pinang fruit (areca nut) chewed with sirih (betel) leaves. But there is also a folklore that mention that term Minangkabau came from a popular legend that was derived from a territorial dispute between a people and a prince from a neighbouring region. To avoid the battle, the local people proposed a fight to the death between two water buffaloes (kabau) to settle the dispute. The prince agreed and produced the largest, meanest, most aggressive buffalo. The villagers on other hand produced a hungry baby calf with its small horns ground to be as sharp as knives. Seeing the adult buffalo across the field, the calf ran forward, hoping for milk. The big buffalo saw no threat in the baby buffalo and paid no attention to it, looking around for a worthy opponent. But when the baby thrust his head under the big bull's belly, looking for an udder, the sharpened horns punctured and killed the bull giving the villagers their victory (menang, hence minang kabau: "victors of the buffalo" which eventually became Minangkabau). That legend, however, is known to be a mere tale and that the word "minang" is too far from the word "menang" which means 'win'.

The legend however has its rebuttals as the word 'minang' refers to the consumption of areca nut (pinang), yet there has not been any popular explanation on the word 'minang' that relates the aforementioned action to the word for "water buffalo".

The first mention of the name Minangkabau as Minanga Tamwan, is in the late 7th century Kedukan Bukit inscription, describing Sri Jayanasa sacred journey from Minanga Tamwan accompanied with 20,000 soldiers heading to Matajap and conquering several areas in the southern of Sumatra.[8]

History

The Minangkabau language is a member of the Austronesian language family, and is closest to the Malay language, though when the two languages split from a common ancestor and the precise historical relationship between Malay and Minangkabau culture is not known. Until the 20th century the majority of the Sumatran population lived in the highlands. The highlands are well suited for human habitation, with plentiful fresh water, fertile soil, a cool climate, and valuable commodities. It is probable that wet rice cultivation evolved in the Minangkabau Highlands long before it appeared in other parts of Sumatra, and predates significant foreign contact.[9]

Adityawarman, a follower of Tantric Buddhism with ties to the Singhasari and Majapahit kingdoms of Java, is believed to have founded a kingdom in the Minangkabau highlands at Pagaruyung and ruled between 1347 and 1375.[10]: 232 The establishment of a royal system seems to have involved conflict and violence, eventually leading to a division of villages into one of two systems of tradition, Bodi-Caniago system based on Adat Perpatih and Koto-Piliang system based on Adat Temenggung, the latter having overt allegiances to royalty.[11] By the 16th century, the time of the next report after the reign of Adityawarman, royal power had been split into three recognised reigning kings. They were the King of the World (Raja Alam), the King of Adat (Raja Adat), and the King of Religion (Raja Ibadat), and collectively they were known as the Kings of the Three Seats (Rajo Tigo Selo).[12] The Minangkabau kings were charismatic or magical figures, but did not have much authority over the conduct of village affairs.[11][13]

Around the 16th century, the Minangkabau started to convert to Islam. The first contact between the Minangkabau and western nations occurred with the 1529 voyage of Jean Parmentier to Sumatra. The Dutch East India Company first acquired gold at Pariaman in 1651, but later moved south to Padang to avoid interference from the Acehnese occupiers. In 1663 the Dutch agreed to protect and liberate local villages from the Acehnese in return for a trading monopoly, and as a result setup trading posts at Painan and Padang. Until early in the 19th century the Dutch remained content with their coastal trade of gold and produce, and made no attempt to visit the Minangkabau highlands. As a result of conflict in Europe, the British occupied Padang from 1781 to 1784 during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, and again from 1795 to 1819 during the Napoleonic Wars.

Late in the 18th century the gold supply which provided the economic base for Minangkabau royalty began to be exhausted. Around the same time other parts of the Minangkabau economy had a period of unparalleled expansion as new opportunities for the export of agricultural commodities arose, particularly with coffee which was in very high demand. A civil war started in 1803 with the Padri fundamentalist Islamic group in conflict with the traditional syncretic groups, elite families and Pagaruyung royals. As a result of a treaty with a number of penghulu and representatives of the Minangkabau royal family, Dutch forces made their first attack on a Padri village in April 1821.[11] The first phase of the war ended in 1825 when the Dutch signed an agreement with the Padri leader Tuanku Imam Bonjol to halt hostilities, allowing them to redeploy their forces to fight the Java War. When fighting resumed in 1832, the reinforced Dutch troops were able to more effectively attack the Padri. The main centre of resistance was captured in 1837, Tuanku Imam Bonjol was captured and exiled soon after, and by the end of the next year the war was effectively over.

With the Minangkabau territories now under the control of the Dutch, transportation systems were improved and economic exploitation was intensified. New forms of education were introduced, allowing some Minangkabau to take advantage of a modern education system. The 20th century marked a rise and cultural and political nationalism, culminating in the demand for Indonesian independence. Later rebellions against the Dutch occupation occurred such as the 1908 Anti-Tax Rebellion and the 1927 Communist uprising. During World War II the Minangkabau territories were occupied by the Japanese, and when the Japanese surrendered in August 1945 Indonesia proclaimed independence. The Dutch attempts to regain control of the area were ultimately unsuccessful and in 1949 the Minangkabau territories became part of Indonesia as the province of Central Sumatra.

In February 1958, dissatisfaction with the centralist and communist-leaning policies of the Sukarno administration triggered a revolt which was centred in the Minangkabau region of Sumatra, with rebels proclaiming the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) in Bukittinggi. The Indonesian military invaded West Sumatra in April 1958 and had recaptured major towns within the next month. A period of guerrilla warfare ensued, but most rebels had surrendered by August 1961. In the years following, West Sumatra was like an occupied territory with Javanese officials occupying most senior civilian, military and police positions.[14] The policies of centralisation continued under the Suharto regime. The national government legislated to apply the Javanese desa village system throughout Indonesia, and in 1983 the traditional Minangkabau nagari village units were split into smaller jorong units, thereby destroying the traditional village social and cultural institutions.[15] In the years following the downfall of the Suharto regime decentralisation policies were implemented, giving more autonomy to provinces, thereby allowing West Sumatra to reinstitute the nagari system.[16]

Historiography

The traditional historiography[5] of the Minangkabau tells of the development of the Minangkabau World (alam Minangkabau) and its adat. These stories are derived from an oral history which was transmitted between generations before the Minangkabau had a written language. The first Minangkabau are said to have arrived by ship and landed on Mount Marapi when it was no bigger than the size of an egg, which protruded from a surrounding body of water. After the waters receded the Minangkabau proliferated and dispersed to the slopes and valleys surrounding the volcano, a region called the darek. The darek is composed of three luhak – Tanah Datar, Agam and Limapuluh Koto. The tambo claims the ship was sailed by a descendant of Alexander the Great (Iskandar Zulkarnain).[17]

A division in Minangkabau adat into two systems is said to be the result of conflict between two half-brothers Datuak Katumangguangan and Datuak Parpatiah nan Sabatang, who were the leaders who formulated the foundations of Minangkabau adat. The former accepted Adityawarman, a prince from Majapahit, as a king while the latter considered him a minister, and a civil war ensued. The Bodi Caniago/Adat perpatih system formulated by Datuak Parpatiah nan Sabatang is based upon egalitarian principles with all panghulu (clan chiefs) being equal while the Koto Piliang /Adat Katumangguangan system is more autocratic with there being a hierarchy of panghulu. Each village (nagari) in the darek was an autonomous "republic", and governed independently of the Minangkabau kings using one of the two adat systems. After the darek was settled, new outside settlements were created and ruled using the Koto Piliang system by rajo who were representatives of the king.[17]

Culture

The Minangkabau have large corporate descent groups, but they traditionally reckon descent matrilineally.[18] A young boy, for instance, has his primary responsibility to his mother's and sisters' clans.[18] It is considered "customary" and ideal for married sisters to remain in their parental home, with their husbands having a sort of visiting status. Not everyone lives up to this ideal, however.[18] In the 1990s, anthropologist Evelyn Blackwood studied a relatively conservative village in Sumatra Barat where only about 22 percent of the households were "matrihouses", consisting of a mother and a married daughter or daughters.[18] Nonetheless, there is a shared ideal among Minangkabau in which sisters and unmarried lineage members try to live close to one another or even in the same house.[18]

Landholding is one of the crucial functions of the suku (female lineage unit). Because Minangkabau men, like Acehnese men, often migrate to seek experience, wealth, and commercial success, the women's kin group is responsible for maintaining the continuity of the family and the distribution and cultivation of the land.[18] These family groups, however, are typically led by a penghulu (headman), elected by groups of lineage leaders.[18] With the agrarian base of the Minangkabau economy in decline, the suku—as a landholding unit—has also been declining somewhat in importance, especially in urban areas.[18] Indeed, the position of penghulu is not always filled after the death of the incumbent, particularly if lineage members are not willing to bear the expense of the ceremony required to install a new penghulu.[18]

The Minangkabau (in short Minang) are also known for their devotion to Islam. A dominant majority of both males and females pray five times a day, fast during the month of Ramadan, and express the desire to make the holy pilgrimage (Hajj) to Mecca at least once in their lifetime. Each Minangkabau neighbourhood has a Musalla, which means "a temporary place of prayer" in Arabic. In the neighbourhood Musalla, men and women pray together, although separated into their respective gender-designated sections. A high percentage of women and girls wear the headscarf.[19]

As early as the age of 7, boys traditionally leave their homes and live in a surau (traditionally: the house of men of a village where the boys learn from older men reading, reciting qur'an, simple math, and other survival skills) to learn religious and cultural (adat) teachings. At the surau during night time (after the Isyak prayers), these youngsters are taught the traditional Minankabau art of self-defence, which is Silek, or Silat in Malay. When they are teenagers, they are encouraged to leave their hometown to learn from schools or from experiences out of their hometown so that when they are adults they can return home wise and 'useful' for the society and can contribute their thinking and experience to run the family or nagari (hometown) when they sit as the member of 'council of maternal uncles and maternal granduncles' (ninik-mamak). This tradition has created Minang communities in many Indonesian cities and towns, which nevertheless are still tied closely to their homeland; a state in Malaysia named Negeri Sembilan especially is heavily influenced by Minang culture because Negeri Sembilan was originally Minangkabau's colony.[20] By acquiring property and education through merantau experience, a young man can attempt to influence his own destiny in positive ways.[18]

Increasingly, married couples go off on merantau; in such situations, the woman's role tends to change.[18] When married couples reside in urban areas or outside the Minangkabau region and a Minang woman marries a non-Minang man, the woman will rely on the protection provided by the husband more than that of her council of uncles. Because in Minang culture marriage is merely a 'commitment of two people' and not at all a 'union', there is no stigma attached to divorce.[18] The Minangkabau were prominent among the intellectual figures in the Indonesian independence movement.[18] Not only were they strongly embedded themselves surrounding Islamic traditions – which counteracted the influence of the Protestant Dutch – they also had a sense of cultural pride just as like every other Sumatran especially with their traditional belief of egalitarianism of "Standing as tall, sitting as low" (that no body stand or sit on an increased stage). They also speak a language closely related to the Malay variant spoken in newly formed Indonesia, which was considerably freer of hierarchical connotations than Javanese.[18] The tradition of merantau also meant that the Minangkabau developed a cosmopolitan bourgeoisie that readily adopted and promoted the ideas of an emerging nation-state.[18] Due to their culture that stresses the importance of learning, Minang people are over-represented in the educated professions in Indonesia, with many ministers from Minang.[21]

Adat derives in part from the ancient animist and buddhist belief system of the Minangkabau, which existed before the arrival of Islam to Sumatra. When precisely the religion spread across the island and was adopted by the Minangkabau is unclear, though it probably arrived in West Sumatra around the 16th century. It is adat that guides matrilineal inheritance, and though it seems that such a tradition might conflict with the precepts of Islam, the Minangnese insist that it does not. To accommodate both, the Minangkabau make a distinction between high and low inheritance. "High inheritance" is the property, including the home and land, which passes among women. "Low inheritance" is what a father passes to his children out of his professional earnings. This latter inheritance follows Islamic law, a complex system which dictates, in part, that sons get twice as much as daughters.[22]

Ceremonies and festivals

Minangkabau ceremonies and festivals include:

- Turun mandi – baby blessing ceremony

- Sunat rasul – circumcision ceremony

- Baralek – wedding ceremony

- Batagak pangulu – clan leader inauguration ceremony. Other clan leaders, all relatives in the same clan and all villagers in the region are invited. The ceremony lasts for seven days or more.

- Turun ka sawah – community work ceremony

- Manyabik – harvesting ceremony

- Hari Rayo – the local observance of Eid al-Fitr

- Adoption ceremony

- Adat ceremony

- Funeral ceremony

- Wild boar hunt ceremony

- Maanta pabukoan – sending food to mother-in-law for Ramadan

- Tabuik – local Mourning of Muharram in the coastal village of Pariaman

- Tanah Ta Sirah, inaugurate a new datuk when the old one died in the few hours (no need to proceed to the batagak pangulu, but the clan must invite all datuk in the region.

- Mambangkik Batang Tarandam, inaugurate a new datuk when the old one died in the past 10 or 50 years and even more, attendance in the Batagak Pangulu ceremony is mandatory.

Performing arts

Traditional Minangkabau music includes saluang jo dendang which consists of singing to the accompaniment of a saluang bamboo flute, and talempong gong-chime music. Dances include the tari piring (plate dance), tari payung (umbrella dance), tari indang (also known as endang or badindin), and tari pasambahan. Demonstrations of the silat martial art are performed. Pidato adat are ceremonial orations performed at formal occasions.

Randai is a folk theatre tradition which incorporates music, singing, dance, drama and the silat martial art. Randai is usually performed for traditional ceremonies and festivals, and complex stories may span a number of nights.[23] It is performed as a theatre-in-the-round to achieve an equality and unity between audience members and the performers.[24] Randai performances are a synthesis of alternating martial arts dances, songs, and acted scenes. Stories are delivered by the acting and singing and are mostly based upon Minangkabau legends and folktales.[23] Randai originated early in the 20th century out of fusion of local martial arts, storytelling and other performance traditions.[25] Men originally played male and female characters in the story but, since the 1960s, women have participated.[23]

Crafts

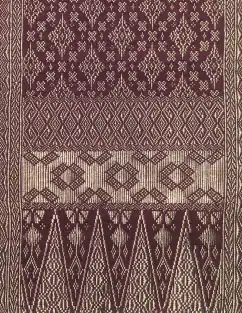

Particular Minangkabau villages specialise in cottage industries producing handicrafts such as woven sugarcane and reed purses, gold and silver jewellery using filigree and granulation techniques, woven songket textiles, wood carving, embroidery, pottery, and metallurgy.

Cuisine

The staple ingredients of the Minangkabau diet are rice, fish, coconut, green leafy vegetables and chili. Meat is mainly limited to special occasions, and beef and chicken are most commonly used. Pork is not halal and not consumed, while lamb, goat and game are rarely consumed for reasons of taste and availability. Spiciness is a characteristic of Minangkabau food: The most commonly used herbs and spices are chili, turmeric, ginger and galangal. Vegetables are consumed two or three times a day. Fruits are mainly seasonal, although fruits such as banana, papaya and citrus are continually available.[26]

Three meals a day are typical with lunch being the most important, except during the fasting month of Ramadan when lunch is not eaten. Meals commonly consist of steamed rice, a hot fried dish and a coconut milk dish, with a little variation from breakfast to dinner.[26] Meals are generally eaten from a plate using the fingers of the right hand. Snacks are more frequently eaten by people in urban areas than in villages. Western food has had little impact upon Minangkabau consumption and preference.[26]

Rendang is a dish which is considered to be a characteristic of Minangkabau culture; it is cooked 4–5 times a year.[26] This particular dish is one of the world's renowned dish, especially after crowned the Best Food in CNN's World's 50 Best Foods in 2011 and 2017 by a CNN poll. Other characteristic dishes include Asam Padeh, Soto Padang, Sate Padang, Dendeng Balado (beef with chili sauce).

Food has a central role in the Minangkabau ceremonies which honour religious and life-cycle rites.

Minangkabau food is popular among Indonesians and restaurants are present throughout Indonesia. Nasi Padang restaurants, named after the capital of West Sumatra, are known for placing a variety of Minangkabau dishes on a customer's table with rice and billing only for what is taken.[27] Nasi Kapau is another restaurant variant which specialises in dishes using offal and tamarind to add a sourness to the spicy flavour.[28]

Architecture

Rumah gadang (Minangkabau: 'big house') or rumah bagonjong (Minangkabau: 'spired roof house') are the traditional homes of the Minangkabau. The architecture, construction, internal and external decoration, and the functions of the house reflect the culture and values of the Minangkabau. A rumah gadang serves as a residence, a hall for family meetings, and for ceremonial activities. The rumah gadang is owned by the women of the family who live there – ownership is passed from mother to daughter.[29]

The houses have dramatic curved roof structures with multi-tiered, upswept gables. They are also well distinguished by their rooflines which curve upward from the middle and end in points, in imitation of the upward-curving horns of the water buffalo that supposedly eked the people their name (i.e. "victors of the buffalo"). Shuttered windows are built into walls incised with profuse painted floral carvings. The term rumah gadang usually refers to the larger communal homes, however, smaller single residences share many of its architectural elements.

Oral traditions and literature

Minangkabau culture has a long history of oral traditions. One is the pidato adat (ceremonial orations) which are performed by clan chiefs (panghulu) at formal occasions such as weddings, funerals, adoption ceremonies, and panghulu inaugurations. These ceremonial orations consist of many forms including pantun, aphorisms (papatah-patitih), proverbs (pameo), religious advice (petuah, parables (tamsia), two-line aphorisms (gurindam), and similes (ibarat).

Minangkabau traditional folktales (kaba) consist of narratives that present the social and personal consequences of either ignoring or observing the ethical teachings and the norms embedded in the adat. The storyteller (tukang kaba) recites the story in poetic or lyrical prose while accompanying himself on a rebab.

A theme in Minangkabau folktales is the central role mothers and motherhood has in Minangkabau society, with the folktales Rancak di Labuah and Malin Kundang being two examples. Rancak di Labuah is about a mother who acts as teacher and adviser to her two growing children. Initially her son is vain and headstrong and only after her perseverance does he become a good son who listens to his mother.[30] Malin Kundang is about the dangers of treating your mother badly. A sailor from a poor family voyages to seek his fortune, becoming rich and marrying. After refusing to recognise his elderly mother on his return home, being ashamed of his humble origins, he is cursed and dies when a storm ensues and turn him along with his ship to stone. The said stone is in Air Manis beach and is known by locals as batu Malin Kundang.[30]

Other popular folktales also relate to the important role of the woman in Minangkabau society. In the Cindua Mato epic the woman is the source of wisdom, while in the Sabai nan Aluih she is a gentle girl who takes action. Cindua Mato (Staring Eye) is about the traditions of Minangkabau royalty. The story involves a mythical Minangkabau queen, Bundo Kanduang, who embodies the behaviours prescribed by adat. Cindua Mato, a servant of the queen, uses magic to defeat hostile outside forces and save the kingdom.[31] Sabai nan Aluih (The genteel Sabai) is about a girl named Sabai who despite being famous for being a gentle girl with perfect wife skills, avenged the murder of her father by a powerful and evil ruler from a neighbouring village. After her father's death, her cowardly elder brother refuses to confront the murderer and so Sabai decided to take matters into her own hands. She seeks out the murderer and shoots him in revenge.[23]

Matrilineage

The Minangkabau are the largest matrilineal society in the world, with property, family name and land passing down from mother to daughter,[32] while religious and political affairs are the responsibility of men, although some women also play important roles in these areas. This custom is called Lareh Bodi-Caniago and is known as adat perpatih in Malaysia. Today 4.2 million Minangs live in the homeland of West Sumatra.

As one of the world's most populous (as well as politically and economically influential) matrilineal ethnicities, Minangkabau gender dynamics have been extensively studied by anthropologists. The adat (Minangkabau: Adaik) traditions have allowed Minangkabau women to hold a relatively advantageous position in their society compared to most patriarchal societies, because though they do not rule, they are at the center of their society.

Language

The Minangkabau language (Baso Minangkabau) is an Austronesian language belonging to the Malayic linguistic subgroup, which in turn belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch. The Negri Sembilan dialect of Malay used by people in the aforementioned state is closely related to it due to the fact many of the population are descendants of Minangkabau immigrants.

The language has a number of dialects and sub-dialects, but native Minangkabau speakers generally have no difficulty understanding the variety of dialects. The differences between dialects are mainly at the phonological level, though some lexical differences also exist. Minangkabau dialects are regional, consisting of one or more villages (nagari), and usually correspond to differences in customs and traditions. Each sub-village (jorong) has its own sub-dialect consisting of subtle differences which can be detected by native speakers.[33] The Padang dialect has become the lingua franca for people of different language regions.[34]

The Minangkabau society has a diglossia situation, whereby they use their native language for everyday conversations, while the Malay language is used for most formal occasions, in education, and in writing, even to relatives and friends.[33] The Minangkabau language was originally written using the Jawi script, an adapted Arabic alphabet. Romanization of the language dates from the 19th century, and a standardised official orthography of the language was published in 1976.[34]

| Denominations | ISO 639-3 | Population (as of) | Dialects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minangkabau | min | 6,500,000 (1981) | Agam, Payakumbuh, Tanah Datar, Sijunjung, Batu Sangkar-Pariangan, Singkarak, Pariaman, Orang Mamak, Ulu, Kampar Ocu, Rokan, Pasaman, Rao, Kuantan, Kerinci-Minangkabau, Pesisir, Aneuk Jamee (Jamee), Painan, Penghulu, Mukomuko. | ||

| Source: Gordon (2005).[35] | |||||

Despite widespread use of Malay in both Malaysia and Indonesia, they do have their own mother tongue; the Minangkabau language shares many similar words with Malay, yet it has a distinctive pronunciation and some grammatical differences rendering it unintelligible to Malay speakers.[36]

Customs and religion

Prior to conversion to Islam, Buddhism, especially Tantric Buddhism was popular in the region. Buddhism in central Sumatra is attested by the Padang Roco Inscription, which states that an Avalokiteśvara was brought from Java to Dharmasraya, and this act brought great happiness to the people.[37] Influential Buddhist kingdoms thrived in the area, including the Pagaruyung Kingdom and Melayu Kingdom.

Animism had also been an important component of Minangkabau culture. Even after the penetration of Islam into Minangkabau society in the 16th century, animistic beliefs were not extinguished. In this belief system, people were said to have two souls, a real soul and a soul which can disappear called the semangat. Semangat represents the vitality of life and it is said to be possessed by all living creatures including animals and plants. An illness may be explained as the capture of the semangat by an evil spirit, and a shaman (pawang) may be consulted to conjure invisible forces and bring comfort to the family. Sacrificial offerings can be made to placate the spirits, and certain objects such as amulets are used as protection.[38]

Until the rise of the Padri movement late in the 18th century, Islamic practices such as prayers, fasting and attendance at mosques had been weakly observed in the Minangkabau highlands. The Padri were inspired by the Wahhabi movement in Mecca, and sought to eliminate societal problems such as tobacco and opium smoking, gambling and general anarchy by ensuring the tenets of the Koran were strictly observed. All Minangkabau customs allegedly in conflict with the Koran were abolished. Although the Padri were eventually defeated by the Dutch, during this period the relationship between adat and religion was reformulated. Previously adat (customs) were said to be based upon appropriateness and propriety, but this was changed so that adat was more strongly based upon Islamic precepts.[4][39]

The Minangkabau strongly profess Islam while at the same time also following their ethnic traditions, or adat. The Minangkabau adat was derived from hereditary wisdom before the arrival of Islam. The present relationship between Islam and adat is described in the saying "traditions [adat] are founded upon the [Islamic] law, and the law founded upon the Qur'an" (adat nan kawi', syara' nan lazim).[5]

With the Minangkabau highlands being the heartland of their culture, and with Islam likely entering the region from coast it is said that "custom descended, religion ascended" (adat manurun, syarak mandaki).[12]

Demographics

Minangkabau Population Breakdown

This table contains Minangkabau population breakdown in Indonesia

| Province | Minangkabau Population |

|---|---|

| West Sumatra | 4,219,729 |

| Riau | 676,948 |

| North Sumatra | 333,241 |

| Jakarta | 272,018 |

| West Java | 241,169 |

| Jambi | 163,760 |

| Riau Islands | 162,452 |

| Banten | 95,845 |

| Bengkulu | 71,472 |

| Lampung | 69,652 |

| Riau Islands | 64,603 |

| Banten | 33,112 |

| Indonesia | 6,462,713 |

Overseas Minangkabau

Over half of the Minangkabau people can be considered overseas Minangkabaus. They make up the majority of the population of Negeri Sembilan, Saribas (in Malaysia) as well as Pekanbaru and Dumai (in Indonesia). They also form a significant minority in the populations of Jakarta, Bandung, Medan, Batam, Surabaya and Palembang in Indonesia as well as Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Singapore and Brunei Darussalam in the rest of the Malay world.[40] Minangkabaus have also emigrated as skilled professionals and merchants to the Netherlands, United States, Saudi Arabia and Australia.[41] In the overseas (rantau), they have a reputation for being shrewd merchants.[42] The matrilineal culture and economic conditions in West Sumatra have made the Minangkabau people one of the most mobile ethnic group in Maritime Southeast Asia.

For most of the Minangkabau people, wandering is an ideal way to reach maturity and success; as a consequence, they exercised great influence in the politics of many kingdom and states in Maritime Southeast Asia. Overseas Minangkabau are also great influence developing Indonesian, Malaysian, and Singaporean culture, mainly language, culinary, music, and martial art.[43]

Notable Minangkabau

The Minangkabau are famous for their dedication to knowledge, as well as the widespread diaspora of their men throughout southeast Asia, the result being that Minangs have been disproportionately represented in positions of economic and political power throughout the region. The co-founder of the Republic of Indonesia, Mohammad Hatta, was a Minang, as were the first President of Singapore, Yusof bin Ishak, and the first Supreme Head of State or Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia, Tuanku Abdul Rahman.

The Minangkabau are known as a society that places top priority in high education and thus they are widespread across Indonesia and foreign countries in a variety of professions and expertise such as politicians, writers, scholars, teachers, journalists, and businesspeople. Outside West Sumatra, they are mostly an urban people, forming part of expanding Indonesia's middle-class.[44] Based on a relatively small population, Minangkabau is one of the most successful.[45] According to Tempo magazine (2000 New Year special edition), six of the top ten most influential Indonesians of the 20th century were Minang.[46] Three out of the four Indonesian founding fathers are Minangkabau people.[47][48]

Many people of Minangkabau descent have held prominent positions in the Indonesian and Malay nationalist movements.[49] In 1920–1960, the political leadership in Indonesian was replete with Minangkabau people, such as Mohammad Hatta a former Indonesian government prime minister and vice-president, Agus Salim a former Indonesian government minister, Tan Malaka international communist leader and founder of PARI and Murba, Sutan Sjahrir a former Indonesian government prime minister and founder of Socialist Party of Indonesia, Muhammad Natsir a former Indonesian government prime minister and founder of Masyumi, Assaat a former Indonesian president, and Abdul Halim a former Indonesian government prime minister. During the liberal democracy era, Minangkabau politician dominated Indonesian parliament and cabinets. They were diversely affiliated to all of the existing factions, such as Islamist, nationalist, socialist and communist.

Minangkabau writers and journalists have made significant contributions to modern Indonesian literature. These include authors Marah Roesli, Abdul Muis, Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana, Idrus, Hamka, and Ali Akbar Navis; poets Muhammad Yamin, Chairil Anwar, and Taufik Ismail; and journalists Djamaluddin Adinegoro, Rosihan Anwar, and Ani Idrus. Many prominent Indonesian novels were written by Minangkabau writers and later influenced the development of modern Indonesian language.[50]

Moreover, there are also significant number of Minangkabau people in the popular entertainment industry, such as movie directors Usmar Ismail and Nasri Cheppy; movie producer Djamaluddin Malik, screenwriter Arizal and Asrul Sani; actor and actress Soekarno M. Noer, Rano Karno, Camelia Malik, Eva Arnaz, Nirina Zubir, Titi Rajo Bintang, and Dude Herlino, as well as singers Fariz RM, Bunga Citra Lestari, Nazril Irham, Dorce Gamalama, Afgansyah Reza, Sherina Munaf, and Tulus.

Nowadays, apart of Chinese Indonesian, Minangkabau people have made significant contributions to Indonesia's economic activities. Minangkabau businessmen are also notable in hospitality sector, media industry, healthcare, publisher, automotive, and textile trading. Some of them are industrialists include Hasyim Ning, Fahmi Idris, Abdul Latief, and Basrizal Koto.

Historically, Minangs had also settled outside West Sumatra, migrating as far as the south Philippines by the 14th century. Raja Bagindo was the leader of the forming polity in Sulu, Philippines, which later turned into the Sultanate of Sulu.[51] The Minangkabaus migrated to the Malay peninsula in the 14th century and began to take control of the local politics. In 1773, Raja Melewar was appointed the first Yamtuan Besar of Negeri Sembilan.

Minangkabaus have filled many political positions in Malaysia and Singapore, namely the first President of Singapore, Yusof Ishak; the first Supreme Head of State (Yang di-Pertuan Agong) of the Federation of Malaya, Tuanku Abdul Rahman; and many Malaysian government ministers, such as Aishah Ghani, Amirsham Abdul Aziz, Aziz Ishak, Ghazali Shafie, Rais Yatim and Khairy Jamaluddin. They are also known for their significant contributions to Malaysian and Singaporean culture, such as Zubir Said, who composed Majulah Singapura (the national anthem of Singapore); the Singaporean musician, Wandly Yazid; the Malaysian film director, U-Wei Haji Saari; the linguist, Zainal Abidin Ahmad; as well as business and economic activities, such as Mohamed Taib bin Haji Abdul Samad, Mokhzani Mahathir, Kamarudin Meranun and Tunku Tan Sri Abdullah.

Notable people of Minangkabau descent outside of the Malay world include member of the House of Representatives of the Netherlands, Rustam Effendi; Ahmad Khatib, the imam (head) of the Shafi'i school of law at Masjid al-Haram; and Khatib's grandson Fouad Abdulhameed Alkhateeb as Saudi Arabian ambassador.

See also

References

General

- Dobbin, Christine (1983). Islamic Revivalism in a Changing Peasant Economy: Central Sumatra, 1784–1847. Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0155-9.

- Frey, Katherine Stenger (1986). Journey to the land of the earth goddess. Gramedia Publishing.

- Kahin, Audrey (1999). Rebellion to Integration: West Sumatra and the Indonesian Polity. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-395-4.

- Sanday, Peggy Reeves (2004). Women at the Center: Life in a Modern Matriarchy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8906-7.

- Summerfield, Anne; Summerfield, John (1999). Walk in Splendor: Ceremonial Dress and the Minangkabau. UCLA. ISBN 0-930741-73-0.

Notes

- ↑ Minangkabau people Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2015 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010 (PDF). Badan Pusat Statistik. 2011. ISBN 9789790644175. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Minangkabau in Malaysia". Joshua Project. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- 1 2 Blackwood, Evelyn (2000). Webs of Power: Women, Kin, and Community in a Sumatran Village. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9911-0.

- 1 2 3 Alam, Sutan Gagar (6 July 1856). "Collective volume with texts in Malay, Minangkabau, Arabic script (1-2) Subtitle No. 61. Oendang oendang adat Lembaga : Tambo Minangkabau; and other texts Or. 12.182". Sakolah Malayu. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ↑ Miksic, John (2004), From megaliths to tombstones: the transition from pre-history to early Islamic period in highland West Sumatra

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (2001). "Understanding Melayu (Malay) as a Source of Diverse Modern Identities". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000157. PMID 19192500. S2CID 38870744.

- ↑ R. Ng. Poerbatjaraka, Riwajat Indonesia. Djilid I, 1952, Jakarta: Yayasan Pembangunan

- ↑ Miksic, John (2004). "From megaliths to tombstones: the transition from pre-history to early Islamic period in highland West Sumatra". Indonesia and the Malay World. 32 (93): 191–210. doi:10.1080/1363981042000320134. S2CID 214651183.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- 1 2 3 Dobbin, Christine (1977). "Economic change in Minangkabau as a factor in the rise of the Padri movement, 1784–1830". Indonesia. Indonesia, Vol. 23. 23 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2307/3350883. hdl:1813/53633. JSTOR 3350883.

- 1 2 Abdullah, Taufik (October 1966). "Adat and Islam: An Examination of Conflict in Minangkabau". Indonesia. Indonesia, Vol. 2. 2 (2): 1–24. doi:10.2307/3350753. hdl:1813/53394. JSTOR 3350753.

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (2005). An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and Other Histories of Sumatra. National University of Singapore Press. ISBN 9971-69-298-8.

- ↑ Kahin (1999), pages 165–229

- ↑ Kahin (1999), pages 257–261

- ↑ Tedjasukmana, Jason (12 March 2001). "Success Story". Time Inc. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- 1 2 Summerfield (1999), pages 48–49

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Kuipers, Joel C. "Minangkabau". In Indonesia: A Country Study Archived 15 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine (William H. Frederick and Robert L. Worden, eds.). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (2011).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Bhanbhro, Sadiq. "Indonesia's Minangkabau culture promotes empowered Muslim women". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ↑ Michael G. Peletz, A Share of the Harvest: Kinship, Property, and Social History Among the Malays of Rembau, 1988

- ↑ Crawford Young, The Politics of Cultural Pluralism, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1976

- ↑ Shapiro, Danielle (4 September 2011). "Indonesia's Minangkabau: The World's Largest Matrilineal Society". Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Pauka, Kirstin (1998). "The Daughters Take Over? Female Performers in Randai Theatre". The Drama Review. 42 (1): 113–121. doi:10.1162/105420498760308706. S2CID 57565023.

- ↑ Pauka, Kirstin; Askovic, Ivana; Polk, Barbara (2003). "Umbuik Mudo and the Magic Flute: A Randai Dance-Drama". Asian Theatre Journal. 20 (2): 113. doi:10.1353/atj.2003.0025. S2CID 161392351.

- ↑ Cohen, Matthew Isaac (2003). "Look at the Clouds: Migration and West Sumatran 'Popular' Theatre". New Theatre Quarterly. 19 (3): 214–229. doi:10.1017/S0266464X03000125. S2CID 191475739.

- 1 2 3 4 Lipoeto, Nur I; Agus, Zulkarnain; Oenzil, Fadil; Masrul, Mukhtar; Wattanapenpaiboon, Naiyana; Wahlqvist, Mark L (February 2001). "Contemporary Minangkabau food culture in West Sumatra, Indonesia". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Blackwell Synergy. 10 (1): 10–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.2001.00201.x. PMID 11708602.

- ↑ Witton, Patrick (2002). World Food: Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. p. 183. ISBN 1-74059-009-0.

- ↑ Owen, Sri (1999). Indonesian Regional Food and Cookery. Frances Lincoln Ltd. ISBN 0-7112-1273-2.

- ↑ Sanday, Peggy Reeves (9 December 2002). "Matriarchy and Islam Post 9/11: A Report from Indonesia". Peggy Reeves Sanday - UPenn. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- 1 2 Dahsinar (1971). Si Malin Kundang. Balai Pustaka.

- ↑ Abdullah, Taufik (1970). "Some Notes on the Kaba Tjindua Mato: An Example of Minangkabau Traditional Literature". Indonesia. Indonesia, Vol. 9. 9 (Apr): 1–22. doi:10.2307/3350620. hdl:1813/53478. JSTOR 3350620.

- ↑ Rathina Sankari (22 September 2016). "World's largest matrilineal society". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 Anwar, Khaidir (June 1980). "Language use in Minangkabau society". Indonesia and the Malay World. 8 (22): 55–63. doi:10.1080/03062848008723789.

- 1 2 Campbell, George L. (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20298-1.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Archived from the original (online version) on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ↑ "Catatan Kritis untuk Buku 'Sejarah Minangkabau, Loanwords, dan Kreativitas Berbahasa Urang Awak'". Padangkita.com (in Indonesian). 1 March 2021. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ↑ Muljana, Slamet, 1981, Kuntala, Sriwijaya Dan Suwarnabhumi, Jakarta: Yayasan Idayu, hlm. 223.

- ↑ Dobbin (1983), pages 117–118

- ↑ Dobbin, Christine (1972). "Tuanku Imam Bondjol, (1772–1864)". Indonesia. 13 (April): 4–35.

- ↑ Mochtar Naim, Zulqaiyyim, Hasanuddin, Gusdi Sastra; Menelusuri Jejak Melayu-Minangkabau, Yayasan Citra Budaya Indonesia, 2002

- ↑ http://www.padeknews.com Archived 2 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine Warga Minang Melbourne Australia Dilepas Naik Haji Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jeffrey Hadler, Muslims and Matriarchs: Cultural Resilience in Indonesia through Jihad and Colonialism, 2013

- ↑ Timothy P. Daniels, Building Cultural Nationalism in Malaysia: Identity, Representation, and Citizenship, 2005

- ↑ Nancy Tanner, Disputing and Dispute Settlement Among the Minangkabau of Indonesia, Cornell University Press, 1969

- ↑ Kato, Tsuyoshi (2005). Adat Minangkabau dan merantau dalam perspektif sejarah. PT Balai Pustaka. p. 2. ISBN 979-690-360-1.

- ↑ . Majalah Tempo Edisi Khusus Tahun 2000. December 1999.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Tim Wartawan Tempo, "4 Serangkai Pendiri Republik", Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, Jakarta (2010)

- ↑ 4 of Indonesian founding fathers are Soekarno, Hatta, Sutan Sjahrir, and Tan Malaka

- ↑ Nasir, Zulhasril. Tan Malaka dan Gerakan Kiri Minangkabau.

- ↑ Swantoro. Dari Buku ke Buku, Sambung Menyambung Menjadi Satu.

- ↑ Asian Studies, Volume 16–18; Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines System, 1978