.jpg.webp)  Lion drawings from the Chauvet Cave, 37,000 to 33,500 years old, and a map of Aurignacian sites. | |

| Geographical range | Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Period | Upper Paleolithic |

| Dates | c. 43,000 – c. 28,000 BP[1][2] |

| Type site | Aurignac |

| Preceded by | Ahmarian, Châtelperronian |

| Followed by | Gravettian, Mal'ta–Buret' culture |

| Defined by | Breuil and Cartailhac, 1906[3] |

The Aurignacian (/ɔːrɪɡˈneɪʃən/) is an archaeological industry of the Upper Paleolithic associated with Early European modern humans (EEMH) lasting from 43,000 to 26,000 years ago. The Upper Paleolithic developed in Europe some time after the Levant, where the Emiran period and the Ahmarian period form the first periods of the Upper Paleolithic, corresponding to the first stages of the expansion of Homo sapiens out of Africa.[4] They then migrated to Europe and created the first European culture of modern humans, the Aurignacian.[5]

The Proto-Aurignacian and the Early Aurignacian stages are dated between about 43,000 and 37,000 years ago. The Aurignacian proper lasted from about 37,000 to 33,000 years ago. A Late Aurignacian phase transitional with the Gravettian dates to about 33,000 to 26,000 years ago.[6][5] The type site is the Cave of Aurignac, Haute-Garonne, south-west France. The main preceding period is the Mousterian of the Neanderthals.

One of the oldest examples of figurative art, the Venus of Hohle Fels, comes from the Aurignacian or Proto-Gravettian and is dated to between 40,000 and 35,000 years ago (though now earlier figurative art may be known, see Lubang Jeriji Saléh). It was discovered in September 2008 in a cave at Schelklingen in Baden-Württemberg in western Germany. The German Lion-man figure is given a similar date range.

A "Levantine Aurignacian" culture is known from the Levant, with a type of blade technology very similar to the European Aurignacian, following chronologically the Emiran and Early Ahmarian in the same area of the Near East, and also closely related to them.[7] The Levantine Aurignacian may have preceded European Aurignacian, but there is a possibility that the Levantine Aurignacian was rather the result of reverse influence from the European Aurignacian: this remains unsettled.[8]

Main characteristics

The Aurignacians are part of the wave of anatomically modern humans thought to have spread from Africa through the Near East into Paleolithic Europe, and became known as European early modern humans, or Cro-Magnons.[4] This wave of anatomically modern humans includes fossils of the Ahmarian, Bohunician, Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian cultures, extending throughout the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), covering the period of roughly 48,000 to 15,000 years ago.[4] In terms of population, the Aurignacian cultural complex is chronologically associated with the human remains of Goyet Q116-1, while the subsequent Gravettian is associated with the Vestonice cluster.[9]

The Aurignacian tool industry is characterized by worked bone or antler points with grooves cut in the bottom. Their flint tools include fine blades and bladelets struck from prepared cores rather than using crude flakes.[10] The people of this culture also produced some of the earliest known cave art, such as the animal engravings at Trois Freres and the paintings at Chauvet cave in southern France. They also made pendants, bracelets, and ivory beads, as well as three-dimensional figurines. Perforated rods, thought to be spear throwers or shaft wrenches, also are found at their sites.

Art

Aurignacian figurines have been found depicting faunal representations of the time period associated with now-extinct mammals, including mammoths, rhinoceros, and tarpan, along with anthropomorphized depictions that may be interpreted as some of the earliest evidence of religion.

Many 35,000-year-old animal figurines were discovered in the Vogelherd Cave in Germany.[11] One of the horses, amongst six tiny mammoth and horse ivory figures found previously at Vogelherd, was sculpted as skillfully as any piece found throughout the Upper Paleolithic. The production of ivory beads for body ornamentation was also important during the Aurignacian. The famous paintings in Chauvet cave date from this period.

Typical statuettes consist of women that are called Venus figurines. They emphasize the hips, breasts, and other body parts associated with fertility. Feet and arms are lacking or minimized. One of the most ancient figurines is the Venus of Hohle Fels, discovered in 2008 in the Hohle Fels cave in Germany. The figurine has been dated to 35,000 years ago and is the earliest known, undisputed example of a depiction of a human being in prehistoric art.[12][13] The Lion-man of Hohlenstein-Stadel, found in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave of Germany's Swabian Alb and dated to 40,000 years ago, is the oldest known anthropomorphic animal figurine in the world.

Aurignacian finds include bone flutes. The oldest undisputed musical instrument was the Hohle Fels Flute discovered in the Hohle Fels cave in Germany's Swabian Alb in 2008.[14] The flute is made from a vulture's wing bone perforated with five finger holes, and dates to approximately 35,000-40,000 years ago.[14] A flute was also found at the Abri Blanchard in southwestern France.[15]

Gallery

_1.png.webp) Decorated ivory pendant from Stajnia Cave, Poland, c. 41,500 BP[16]

Decorated ivory pendant from Stajnia Cave, Poland, c. 41,500 BP[16] Bone flute, 35,000-40,000 years old

Bone flute, 35,000-40,000 years old The Adorant of Geissenklösterle, Germany

The Adorant of Geissenklösterle, Germany The Adorant of Geissenklösterle, reverse side with notches

The Adorant of Geissenklösterle, reverse side with notches The Venus of Hohle Fels figurine (height 6cm), 35,000 BP

The Venus of Hohle Fels figurine (height 6cm), 35,000 BP Horse figurine from Vogelherd Cave, Germany

Horse figurine from Vogelherd Cave, Germany Animal figurine from Vogelherd Cave

Animal figurine from Vogelherd Cave Chauvet Cave painting, France

Chauvet Cave painting, France Possible musical bow from Geisenklösterle, Germany

Possible musical bow from Geisenklösterle, Germany Lion head sculpture, Vogelherd cave

Lion head sculpture, Vogelherd cave Lion sculpture, Vogelherd cave

Lion sculpture, Vogelherd cave Mammoth sculpture, Vogelherd cave

Mammoth sculpture, Vogelherd cave Venus of Galgenberg, Austria

Venus of Galgenberg, Austria Carved ivory from Brillenhöhle cave

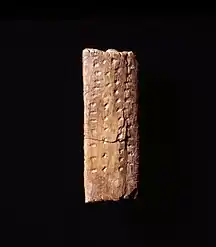

Carved ivory from Brillenhöhle cave Engraved plaque from Abri Lartet, France

Engraved plaque from Abri Lartet, France Engraved plaque from Abri Blanchard, France

Engraved plaque from Abri Blanchard, France Aurignacian jewellery, Belgium

Aurignacian jewellery, Belgium A painting of a hand in the Cave of Aurignac, France

A painting of a hand in the Cave of Aurignac, France Jewelry, Fazael, Israel, Upper Paleolithic.

Jewelry, Fazael, Israel, Upper Paleolithic. A carving of a running horse, Hayonim Cave, Levant.

A carving of a running horse, Hayonim Cave, Levant.

Tools

Stone tools from the Aurignacian culture are known as Mode 4, characterized by blades (rather than flakes, typical of mode 2 Acheulean and mode 3 Mousterian) from prepared cores. Also seen throughout the Upper Paleolithic is a greater degree of tool standardization and the use of bone and antler for tools. Based on the research of scraper reduction and paleoenvironment, the early Aurignacian group moved seasonally over greater distances to procure reindeer herds within cold and open environments than those of the earlier tool cultures.[17]

A bone point

A bone point

Aurignacian blades

Aurignacian blades.jpg.webp) Dufour bladelet

Dufour bladelet Bone tools, Hayonim Cave, 30000 BP.

Bone tools, Hayonim Cave, 30000 BP. Aurignacian microliths

Aurignacian microliths

Population

A 2019 demographic analysis estimated a mean population of 1,500 persons (upper limit: 3,300; lower limit: 800) for western and central Europe during the Aurignacian period (~42,000 to 33,000 y cal BP).[21]

A 2005 study estimated the population of Upper Palaeolithic Europe from 40–30 thousand years ago was 1,738–28,359 (average 4,424).[22]

Association with modern humans

The sophistication and self-awareness demonstrated in the work led archaeologists to consider the makers of Aurignacian artifacts the first modern humans in Europe. Human remains and Late Aurignacian artifacts found in juxtaposition support this inference. Although finds of human skeletal remains in direct association with Proto-Aurignacian technologies are scarce in Europe, the few available are also probably modern human. The best dated association between Aurignacian industries and human remains are those of at least five individuals from the Mladeč caves in the Czech Republic, dated by direct radiocarbon measurements of the skeletal remains to at least 31,000–32,000 years old.[10]

At least three robust, but typically anatomically-modern individuals from the Peștera cu Oase cave in Romania, were dated directly from the bones to ca. 35,000–36,000 BP. Although not associated directly with archaeological material, these finds are within the chronological and geographical range of the Early Aurignacian in southeastern Europe.[10] On genetic evidence it has been argued that both Aurignacian and the Dabba culture of North Africa came from an earlier big game hunting Levantine Aurignacian culture of the Levant.[23]

Genetics

.png.webp)

In a genetic study published in Nature in May 2016, the remains of an early Aurignacian individual, Goyet Q116-1 from modern-day Belgium, were examined. He belonged to the paternal haplogroup C1a and the maternal haplogroup M.[24] Haplogroups identified in other Aurignacian samples are the paternal haplogroups C1b and K2a;[note 1][27] and mt-DNA haplogroup N, R, and U.[note 2]

The Aurignacian material culture is associated with the expansion of 'early West Eurasians' during the Upper-Paleolithic, replacing or merging with previous Initial Upper Paleolithic cultures to which possibly relates the European Châtelperronian.[29][30]

Location

Europe

Near-East

Asia

Lebanon/Palestine/Israel region

- Contained within a stratigraphic column, along with other cultures.[31]

- Many sites in Siberia including around Lake Baikal, the Ob River valley, and Minusinsk.[31]

.JPG.webp) The entrance to the Potočka Zijalka, a cave in the Eastern Karavanke, where the remains of a human residence dated to the Aurignacian (40,000 to 30,000 BP) were found.[32]

The entrance to the Potočka Zijalka, a cave in the Eastern Karavanke, where the remains of a human residence dated to the Aurignacian (40,000 to 30,000 BP) were found.[32] Entrance porch of the Cave of Aurignac

Entrance porch of the Cave of Aurignac

Interior of Bacho Kiro cave

Interior of Bacho Kiro cave

See also

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

| ↓ Mesolithic |

Notes

- ↑ Kostenki-14 (Russia): C1b, Goyet Q116-1 (Belgium) C1a,[25] Sungir (Russia): C1a2, Ust'-Ishim and Oase-1: K2a[26]

- ↑ Haplogroup N was found in two Gravettian-era fossils, Paglicci 52 Paglicci 12, and is widespread in Central Asia[28]

References

- ↑ Milisauskas, Sarunas (2012-12-06). European Prehistory: A Survey. Springer. ISBN 9781461507512.

- ↑ Shea, John J. (2013-02-28). Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139619387.

- ↑ H. Martin (1906). "Industrie Moustérienne perfectionnée. Station de La Quina (Charente)". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de France (in French). 3 (6): 233–239. doi:10.3406/bspf.1906.7784. JSTOR 27906750.(subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Klein, Richard G. (2009). The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins. University of Chicago Press. p. 610. ISBN 9780226027524.

- 1 2 Wood, Bernard, ed. (2011). "Aurignacian". Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. John Wiley. ISBN 9781444342475.

- ↑ Hoffecker, JF (September 2009). "Out of Africa: modern human origins special feature: the spread of modern humans in Europe". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (38): 16040–5. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616040H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903446106. PMC 2752585. PMID 19571003.. Jacobi, R.M.; Higham, T.F.G.; Haesaerts, P.; Jadin, I.; Basell, L.S. (2010). "Radiocarbon chronology for the Early Gravettian of northern Europe: new AMS determinations for Maisières-Canal, Belgium". Antiquity. 84 (323): 26–40. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099749. S2CID 163089681.

- ↑ Shea, John J. (2013). Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–155. ISBN 9781107006980.

- ↑ Williams, John K. (2006). "The Levantine Aurignacian: a closer look" (PDF). Lisbon: Instituto Português de Arqueologia (Trabalhos de Arqueologia Bar-Yosef O, Zilhão J, Editors. Towards a Definition of the Aurignacian. 45): 317–352.

- ↑ Fu 2016: "GoyetQ116-1 is chronologically associated with the Aurignacian cultural complex. Thus, the subsequent spread of the Vestonice Cluster, which is associated with the Gravettian cultural complex, shows that the spread of the latter culture was mediated at least in part by population movements."

- 1 2 3 Mellars, P. (2006). "Archeology and the Dispersal of Modern Humans in Europe: Deconstructing the Aurignacian". Evolutionary Anthropology. 15 (5): 167–182. doi:10.1002/evan.20103. S2CID 85316570.

- ↑ Finds from the Vogelherd cave Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Conard, Nicholas (2009). "A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany". Nature. 459 (7244): 248–52. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..248C. doi:10.1038/nature07995. PMID 19444215. S2CID 205216692.

- ↑ Henderson, Mark (2009-05-14). "Prehistoric female figure 'earliest piece of erotic art uncovered'". The Times. London.

- 1 2 Conard, Nicholas; et al. (6 August 2009). "New flutes document the earliest musical tradition in southwestern Germany". Nature. 460 (7256): 737–740. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..737C. doi:10.1038/nature08169. PMID 19553935. S2CID 4336590.

- ↑ Richard Leakey & Roger Lewin, Origins Reconsidered: In Search of What Makes Us Human (1992)

- ↑ Talamo, Sahra; et al. (2021). "A 41,500 year-old decorated ivory pendant from Stajnia Cave (Poland)". Scientific Reports. 11: 22078. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1122078T. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01221-6. PMID 34837003. S2CID 244699451.

Here, we report the discovery of the oldest known human-modified punctate ornament, a decorated ivory pendant from the Paleolithic layers at Stajnia Cave in Poland. ... The punctate decorative motif is one of the artistic innovations that developed during the Early Aurignacian in Europe and the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic in the Russian Plains. Thus far, these marks on mobile objects have been interpreted as hunting tallies, arithmetic counting systems, or lunar notation, whereas others have suggested aesthetic purposes. The looping curve represented on the Stajnia pendant is similar to the engraved patterns of the Blanchard plaque. Whether these marks indicate cyclic notations or kill scores remain an open question, although the resemblance with the lunar analemma is striking.

- ↑ Blades, B (2003). "End scraper reduction and hunter-gatherer mobility". American Antiquity. 68 (1): 141–156. doi:10.2307/3557037. JSTOR 3557037. S2CID 164106990.

- ↑ Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Korneliussen, Thorfinn S. (28 November 2014). "Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years". Science. 346 (6213): 1113–1118. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1113S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0114. PMID 25378462. S2CID 206632421.

The few AMH fossils associated with these initial UP industries are morphologically variable. In western Eurasia, the distinctive Aurignacian toolkit, first observed at Willendorf (Austria) by 43.5 ka, became predominant across the earlier range by 39 ka. Although analyses of ancient human genomes have advanced our understanding of the European past, revealing contributions from Paleolithic Siberians, European Mesolithic, and Near Eastern Neolithic groups to the European gene pool, the possible contribution of the earliest Eurasians to these later cultures and to contemporary human populations remains unknown. To investigate this, we sequenced the genome of Kostenki 14 (K14, Markina Gora)

- ↑ Hoffecker, John F. (January 2011). "The early upper Paleolithic of eastern Europe reconsidered". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 20 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1002/evan.20284. PMID 22034081. S2CID 32216495.

The determination of a complete genome from ancient mtDNA extracted from a skeleton associated with Layer III at Kostenki 14 indicates that mtDNA subgroup U2 is represented among the people who occupied the central East European Plain at ca. 35,000 cal BP. This subgroup is widely distributed today in southern and central Asia, the Near East, and Europe, and is linked to one of the oldest genetic markers in Europe, mtDNA haplogroup U. At Kostenki 14, this subgroup is associated with artifacts assigned to the Gorodtsovan Culture but reinterpreted here as an Eastern Aurignacian assemblage.

- ↑ Moiseev, V. G.; Khartanovich, V. I.; Zubova, A. V. (March 2017). "The Upper Paleolithic man from Markina Gora: Morphology vs. genetics?". Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 87 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1134/S1019331617010099. ISSN 1019-3316. S2CID 157720076.

The newly obtained dates make it possible to state that the burial in Markina Gora, according to calibrated data, is dated to within 38700-36200 years ago [8]. By the European scale, these dates synchronized it with the earliest Aurignacian complexes, among which the burial under study has a unique preservation

- ↑ Schmidt, I.; Zimmermann, A. (2019). "Population dynamics and socio-spatial organization of the Aurignacian: Scalable quantitative demographic data for western and central Europe". PLOS ONE. 14 (2): e0211562. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1411562S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211562. PMC 6373918. PMID 30759115.

Demographic estimates are presented for the Aurignacian techno-complex (~42,000 to 33,000 y calBP) and discussed in the context of socio-spatial organization of hunter-gatherer populations. Results of the analytical approach applied estimate a mean of 1,500 persons (upper limit: 3,300; lower limit: 800) for western and central Europe.

- ↑ Bocquet-Appel, J.-P.; Demars, P.-Y.; Noiret, L.; Dobrowsky, D. (2005). "Estimates of Upper Palaeolithic meta-population size in Europe from archaeological data". Journal of Archaeological Science. 32 (11): 1656–1668. Bibcode:2005JArSc..32.1656B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.05.006.

- ↑ Forster, P.; Romano, V.; Olivieri, A.; Achilli, A.; Pala, M.; Battaglia, V.; Fornarino, S.; Al-Zahery, N.; Scozzari, R.; Cruciani, F.; Behar, D. M.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Coudray, C.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; Semino, O.; Bandelt, H.-J.; Torroni, A. (2007). "Timing of a Back-Migration into Africa". Science. 316 (5821): 50–53. doi:10.1126/science.316.5821.50. PMID 17412938. S2CID 34614953., "Sequencing of 81 entire human mitochondrial DNAs (mtDNAs) belonging to haplogroups M1 and U6 reveals that these predominantly North African clades arose in southwestern Asia and moved together to Africa about 40,000 to 45,000 years ago. Their arrival temporally overlaps with the event(s) that led to the peopling of Europe by modern humans and was most likely the result of the same change in climate conditions that allowed humans to enter the Levant, opening the way to the colonization of both Europe and North Africa. Thus, the early Upper Palaeolithic population(s) carrying M1 and U6 did not return to Africa along the southern coastal route of the "out of Africa" exit, but from the Mediterranean area; and the North African Dabban and European Aurignacian industries derived from a common Levantine source."

- ↑ Fu 2016.

- ↑ Fu, Q.; Posth, C. (2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 534 (7606): 200–205. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

- ↑ Sikora, Martin; Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Sousa, Vitor C.; Albrechtsen, Anders; Korneliussen, Thorfinn; Ko, Amy; Rasmussen, Simon; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Nigst, Philip R.; Bosch, Marjolein D.; Renaud, Gabriel; Allentoft, Morten E.; Margaryan, Ashot; Vasilyev, Sergey V.; Veselovskaya, Elizaveta V.; Borutskaya, Svetlana B.; Deviese, Thibaut; Comeskey, Dan; Higham, Tom; Manica, Andrea; Foley, Robert; Meltzer, David J.; Nielsen, Rasmus; Excoffier, Laurent; Mirazon Lahr, Marta; Orlando, Ludovic; Willerslev, Eske (2017). "Ancient genomes show social and reproductive behaviour of early Upper Paleolithic foragers". Science. 358 (6363): 659–662. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..659S. doi:10.1126/science.aao1807. PMID 28982795.

- ↑ Seguin-Orlando, A.; Korneliussen, T. S.; Sikora, M.; Malaspinas, A.-S.; Manica, A.; Moltke, I.; Albrechtsen, A.; Ko, A.; Margaryan, A.; Moiseyev, V.; Goebel, T.; Westaway, M.; Lambert, D.; Khartanovich, V.; Wall, J. D.; Nigst, P. R.; Foley, R. A.; Lahr, M. M.; Nielsen, R.; Orlando, L.; Willerslev, E. (6 November 2014). "Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years". Science. 346 (6213): 1113–1118. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1113S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0114. PMID 25378462. S2CID 206632421.

- ↑ Caramelli, D.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Vernesi, C.; Lari, M.; Casoli, A.; Mallegni, F.; Chiarelli, B.; Dupanloup, I.; Bertranpetit, J.; Barbujani, G.; Bertorelle, G. (May 2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (11): 6593–6597. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.6593C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

- ↑ Vallini, Leonardo; Marciani, Giulia; Aneli, Serena; Bortolini, Eugenio; Benazzi, Stefano; Pievani, Telmo; Pagani, Luca (2022-04-07). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (4): evac045. doi:10.1093/gbe/evac045. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 9021735. PMID 35445261.

The UP branch would have then emerged from a putative OoA population Hub well after 45 ka, a scenario that finds support in previous hypotheses on the appearance of UP techno-complexes (e.g. Aurignacian) in Europe, although the role of migrations and exchange between Europe, Western Asia, and the Levant is still debated (Conard 2002; Mellars 2006; Teyssandier 2006; Davies 2007; Hoffecker 2009; Le Brun-Ricalens et al. 2009; Nigst et al. 2014; Zilhão 2014; Hublin 2015; Bataille et al. 2020; Falcucci et al. 2020).

- ↑ Zwyns, Nicolas (2021-06-20). "The Initial Upper Paleolithic in Central and East Asia: Blade Technology, Cultural Transmission, and Implications for Human Dispersals". Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology. 4 (3): 19. doi:10.1007/s41982-021-00085-6. ISSN 2520-8217.

- 1 2 Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-395-13592-1.

- ↑ Debeljak, Irena; Turk, Matija. "Potočka zijalka". In Šmid Hribar, Mateja; Torkar, Gregor; Golež, Mateja; et al. (eds.). Enciklopedija naravne in kulturne dediščine na Slovenskem – DEDI (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 2012-05-15. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

Sources

- Fu, Qiaomei (May 2, 2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 534 (7606): 200–205. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. hdl:10211.3/198594. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

External links

- Picture Gallery of the Paleolithic (reconstructional palaeoethnology), Libor Balák at the Czech Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Archaeology in Brno, The Center for Paleolithic and Paleoethnological Research