54°26′49″N 3°03′50″W / 54.447°N 3.064°W

The Langdale axe industry (or factory) is the name given by archaeologists to a Neolithic centre of specialised stone tool production in the Great Langdale area of the English Lake District.[1] The existence of the site, which dates from around 4,000–3,500 BC,[2] was suggested by chance discoveries in the 1930s. More systematic investigations were undertaken by Clare Fell[3][4][5] and others[6][7][8] in the 1940s and 1950s, since when several field surveys of varying scope have been carried out.[1][9][10][11][12]

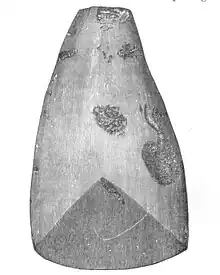

Typical finds include reject axes, rough-outs and blades created by knapping large lumps of the rock found in the scree or perhaps by simple quarrying or opencast mining. Hammerstones have also been found in the scree and other lithic debitage from the industry such as blades and flakes.

The area has outcrops of fine-grained greenstone or hornstone suitable for making polished stone axes. Such axes have been found distributed across Great Britain.[13] The rock is an epidotised greenstone quarried or perhaps just collected from the scree slopes in the Langdale Valley on Harrison Stickle and Pike of Stickle. The nature and extent of the axe-flaking sites making up the Langdale Axe Factory complex are still under investigation. Geological mapping has established that the volcanic tuff used for the axes outcrops along a narrow range of the highest peaks in the locality. Other outcrops in the area are known to have been worked, especially on Harrison Stickle, and Scafell Pike where rough-outs and flakes have been found on platforms below the peaks at and above the 2000- or 3000-foot level.

Recent research has shown that Langdale tuff was used for tools before the Neolithic 'axe factories' were established. In Maryport (Cumbria) it was selected for tool manufacture in the Final Palaeolithic and Mesolithic[14]

Petrographic analysis

Archaeologists are able to identify the unique nature of the Langdale stone by taking sections and examining them using microscopy. The minerals in the rock have a characteristic pattern, using a method known as petrography. They have been able to reconstruct the production methods and trade patterns employed by the axe makers. The Langdale industry produced roughly hewn (or so-called "rough-outs") axes and simple blocks. The highly polished final product were usually made elsewhere, such as at Ehenside Tarn in the western fringes of the Lake District, and all were traded on throughout Britain and Ireland. The Langdale tuff was among the most common of the various rocks used to make axes in the Neolithic period, and are known as Group VI axes. Flint was also commonly used to make polished axes, and mined at several places, but especially at Grimes Graves and Cissbury, and in continental Europe at Spiennes in Belgium, and Krzemionki in Poland.

Polishing the rough surfaces will have improved the mechanical strength of the axe as well as lowering friction when used against wood. Fractures occur more easily in brittle materials like stone when rough owing to the stress concentrations present at sharp corners, holes and other defects in the axe surface. Removing those defects by polishing makes the axe much stronger, and able to withstand impact and shock loads from use. Sandstone was usually used for polishing axes, and whetstones have been found nearby at Ehenside tarn, for example where the rough-outs were polished. Large fixed outcrops were also widely used for polishing, and there are numerous examples across Europe, but relatively few in Britain. That at Fyfield Down near Avebury is an exception, but there must be many more awaiting discovery and publication.

Distribution and use

The stone axes from Langdale have been found at archaeological sites across Britain and Ireland. An unusual concentration of finds occurs in the East of England, particularly Lincolnshire. Francis Pryor[15] attributes this to these axes being particularly valued in this region. He mentions possible religious significance of the axes, perhaps related to the high peaks from which they came. He compares this with confirmed Neolithic flint mines which, apart from Grime's Graves (where flint of exceptionally high quality was mined), were all at prominent elevated locations.

Of all the Neolithic polished stone axes that have been examined in the UK, around 27% come from the Langdale region. This is notable considering there were over 30 sources of material for stone axes from Cornwall to northern Scotland and Ireland.

Whether religious objects or not, the axes must have been of high value, given that they have been "traded" so widely. Some axes appear worn whilst others appear unused, again implying that they were regarded as sacred objects or, perhaps, simply as a display of visible wealth. Some though were used as practical tools. The shape of the polished axes suggests that they were bound in wooden staves and used for forest clearance.

Francis Pryor discusses a flint axe that he found north of Peterborough with fantastic swirling patterns that had been brought out by polishing – but this axe was totally impractical as the patterns were fault lines, making the flint very fragile. However, it must have been valued by its owner and/or maker, bearing in mind the work involved in making it. These facts suggest various interpretations of the purpose of the Langdale axes, which were both beautiful and practical, as well as being traded many miles from their place of production.

Context

The Langdale industry was one of many which extracted hard stone for manufacture into polished axes. The Neolithic period was a time of settlement on the land, and the development of farming on a large scale. Maintenance of the forest cover was necessary in order to plant crops and rear animals, so axes were a staple tool, not just for clearance but also for wood working timber for houses, boats and other structures. Flint was probably the most widely used, simply because it was available from numerous flint mines in the downlands, such as Grimes Graves, Cissbury and Spiennes. Blades from roughing-out from flint and chert could also be used as small knives, arrowheads and other small sharp tools such as burins and awls.

But other hard and tough stones were used, such as igneous rocks from Penmaenmawr in North Wales, and similar working areas to Langdale have been found there. Many other locations for production of axes have been suggested (but not always found) across the country including Tievebulliagh in County Antrim, sites in Cornwall, Scotland and the Charnwood Forest in Leicestershire. It is also likely that bluestone axes were exported from the Preseli hills in Pembrokeshire. The industry was also widely developed elsewhere in the world, such as in Australia at Mount William stone axe quarry which used a similar rock until relatively recent times. The variety of rocks used in polished tools and other artefacts is evident in museum collections, not all of the sources of the rocks having been positively identified. Taking sections is necessarily destructive of part of the artefact, and thus discouraged by many museums. Likewise, the rocks or anvils used to polish the axes are rare in Britain but common in France and Sweden.

Radiocarbon dating at the Langdale stone axe factory site suggests that it was in operation for about 1,000 years during the Neolithic period.

Current thinking links the manufacturers of the axes to some of the first Neolithic stone circles such as that at Castlerigg.[16][17]

Conservation

The altitude and rough terrain of the archaeological sites have protected them from types of damage caused by human settlement in lowland areas. However, Great Langdale is much visited by walkers. People have removed axes (although current thinking is that they should be left in situ) and have caused inadvertent damage to stone scatters by walking.

An attempt to schedule the sites as ancient monuments in the 1980s was thwarted by the lack of reliable mapping.[18] However, English Heritage has been considering questions on how the sites should be managed.[19] Particular attention has been paid to the siting of footpaths to avoid damage to axeworking sites.[18] Since the 1990s eroded paths in the Lake District, including Great Langdale, have been repaired by a "Fix the Fells" project in which the National Trust is the major partner.

Langdale axes are displayed in Cumbria at Kendal Museum and Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle,[20] and in other collections such as the British Museum.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Claris, Philip; Quartermaine, James & Woolley, A. R. (1989). "The Neolithic Quarries and Axe Factory Sites of Great Langdale and Scafell Pike: A New Field Survey" (PDF). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 55 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00005326. ISSN 2050-2729. S2CID 130925089. (For accompanying material see Supplement 1 of same volume).

- ↑ Edinborough, Kevan; Shennan, Stephen; Teather, Anne; Baczkowski, Jon; Bevan, Andrew; Bradley, Richard; Cook, Gordon; Kerig, Tim; Parker Pearson, Mike; Pope, Alexander & Schauer, Peter (2020). "New Radiocarbon Dates Show Early Neolithic Date of Flint-mining and Stone Quarrying in Britain" (PDF). Radiocarbon. Cambridge University Press. 62 (1): 75–105. Bibcode:2020Radcb..62...75E. doi:10.1017/RDC.2019.85. ISSN 0033-8222. S2CID 197554465.

- ↑ Fell, Clare (1949). "A stone-axe factory site, Pike o' Stickle, Great Langdale, Westmorland" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Kendal. 49: 214–215. doi:10.5284/1062802. ISSN 0309-7986 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ Fell, Clare (1950). "The Great Langdale stone-axe factory" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Kendal. 50: 1–13. doi:10.5284/1062772. ISSN 0309-7986 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ Fell, Clare I. (1955). "Further Notes on the Great Langdale Axe-factory" (PDF). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 20 (2): 238–239. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00017710. ISSN 2050-2729. S2CID 112636558.

- ↑ Bunch, Brian & Fell, Clare I. (1949). "A Stone-Axe Factory at Pike of Stickle, Great Langdale, Westmorland" (PDF). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 15: 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00019149. ISSN 2050-2729. S2CID 140588391.

- ↑ Plint, R. G. (1952). "The Great Langdale Stone Axe Factory" (PDF). Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club of the English Lake District. Vol. 16, no. 2. pp. 121–124.

- ↑ Plint, R. G. (1962). "Stone Axe Factory Sites in the Cumbrian Fells" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Kendal. 62: 1–21. doi:10.5284/1062406. ISSN 0309-7986 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ Clough, T. H. McK. (1973). "Excavations on a Langdale axe chipping site in 1969 and 1970" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Kendal. 73: 25–46. doi:10.5284/1062063. ISSN 0309-7986 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ Houlder, C. H. (1979). "The Langdale and Scafell Pike Axe Factory Sites: A Field Survey". In Cummins, W. A. & Clough, T. H. McK. (eds.). Stone Axe Studies: Archaeological, Petrological, Experimental and Ethnographic (PDF). Council for British Archaeology Research Reports. Vol. 23. London: Council for British Archaeology. pp. 87–89. doi:10.5284/1081696. ISSN 0589-9036 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ Schofield, Peter (2005). Stickle Tarn, Great Langdale, Cumbria (PDF) (Report). Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology North. Issue No. 2005-2006/452 (OAN Job No. L9589).

- ↑ Schofield, Peter (2009). Axe Working Sites on Path Renewal Schemes, Central Lake District, Cumbria (PDF) (Report). Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology North. Issue No. 2008-2009/903 (OAN Job No. L10032).

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (1992). Neolithic Britain: New Stone Age Sites of England, Scotland, and Wales. London: Routledge. pp. 60, 62. ISBN 0415058457 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Clarke, Ann & Kirby, Magnus (2022). "Tuff, Flint, and Hazelnuts: Final Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Occupation at Netherhall Road, Maryport, Cumbria". Internet Archaeology (59). doi:10.11141/ia.59.4. ISSN 1363-5387.

- ↑ Pryor, Francis (2003). Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland Before the Romans. Harper Collins. ISBN 0007126921.

- ↑ "Ancient monuments - The Heritage Journal". wordpress.com. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ Article on Castlerigg and the axe industry of Langdale

- 1 2 Axeworking sites on path renewal schemes

- ↑ "National Importance Programme". english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ information about the stone axes that the Tullie House Museum has in its collection