Mexican handcrafted fireworks production is mostly concentrated in the State of Mexico in central Mexico. The self-declared fireworks capital of Mexico is Tultepec, just north of Mexico City. Although the main ingredient for fireworks, gunpowder, was brought by the conquistadors in the 16th century, fireworks became popular in Mexico in the 19th century. Today, it is Latin America’s second largest producer, almost entirely for domestic use, with products ranging from small firecrackers to large shells and frames for pyrotechnics called “castillos” (castles) and “toritos” (little bulls). The industry is artisanal, with production concentrated in family-owned workshops and small factories with a number operating illegally. The relatively informal production and sales of fireworks have made it dangerous with a number of notable accidents in from the late 1990s to the present, despite attempts to safety regulations.

History

Although pre Hispanic cultures had ways of manipulating fire for ceremonial purposes, the popularity of fireworks came to Mexico late, in the 19th century.[1][2] Fireworks were invented by the Chinese, and for ceremonial and religious use, which is their main use today in Mexico.[3]

Fireworks production and use came to Mexico through Europe. The main ingredient for them, gunpowder, came with the conquistadors but for military purposes. The first place to start gunpowder manufacture was Tultepec, which during the colonial period was separate from Mexico City and had an abundance of saltpeter, from which the chemicals could be extracted.[4] The popularity of fireworks begin in the 19th century, after Mexico’s independence.[2][4] Fireworks production, sale and handling is covered by the federal Armas, Municiones, Explosivas y Pirotecnia law, with the aim of reducing the risk associated with the product.[3] This law was enacted in 1963, more geared towards the military. Recent efforts to update the law have included providing training and other measures to extend legal status to irregular manufacturers.[2] Fireworks are a main staple of Mexican religious festivals, especially those for patron saints. However, the main occasion for fireworks use are the celebrations surrounding Mexican Independence, which begins with the reenactment of Father Hidalgo’s cry against the Spanish at 11pm on September 15, 1810. The fireworks are ignited just after the reenactment.[2]

Manufacture

In Latin America, Mexico is the second largest producer of fireworks, after Brazil.[2] There are over 50,000 families in Mexico which manufacture fireworks, many illegally,[2][3] with 40,000 families in sixty municipalities in the State of Mexico alone.[5] Many of these artisans are located in the municipalities of Almoloya de Juárez, Axapusco, Tianguistenco, Tenancingo, Tenango del Valle, Otumba, Capulhuac, Coyotepec, Tecámac and Texcoco, along with the community of San Mateo Otzacatipan.[4][6] However, the biggest producer is the municipality of Tultepec, located just north of Mexico City, which accounts for 25% of all the fireworks produced in Mexico.[2]

There are three internationally recognized pyrotechnic enterprises in Mexico. Lux Pirotecnia is located in Zumpango, known for its rigorous manufacturing methods and participation in international competitions in Europe and Canada.[2] Pirotecnia Reyes won first place at the International Fireworks Competition in Hannover, Germany in 2011 with a fireworks and music show lasting 25 minutes. This enterprise was founded by Manues Reyes Arias who received the 1996 Premio Nacional de las Artes .[7]

Most artisans are trained by their elders with no formal training or formal degrees in chemistry or engineering, although some have abroad for training as well to promote products.[5][8] Artisans buy ingredients in local chemical supply shops and local markets, which are then mixed by hand in family owned workshops and small factories. Everything is made from scratch, with cartridges made of packing tape and scrap paper purchased in bulk. Often, the fireworks are packaged in nothing but old cornmeal and dog food bags.[9] Most artisans are not formal employees, but rather work in the family business. The formulas used by each workshop are individual and guarded by the families that own them.[8] Workshops are ranked with the best artisans receiving the “maestro” (master) title, able to produce elaborate products such as castillos, bombas, toritos and synchronized fireworks/light/music shows.[8]

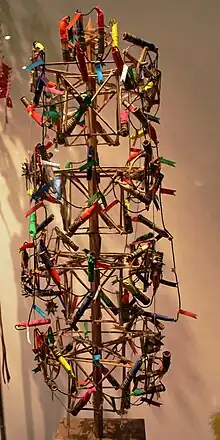

Mexican firework production include a number of explosive objects such as “rocas” (rocks, a kind of powerful firecracker), “vampiros” (vampires), “patas de mula” (mule hooves) and “bombas” (large rockets) as well as frames with pyrotechnics called “castillos” (castles), “toritos” (little bulls), “canastillas” (little baskets) and Judas figures.[6][9] Castillos are generally large wooden frames covered with brilliant flares, which can cost between 20,000 to 250,000 pesos depending on size and complexity.[8][9] These are most often made to honor patron saints or Mexico’s patriot heroes.[8] Toritos are smaller frames in the shape of a bull, designed to be worn or carried by a person as they are lit, chasing passers-by in the street during festivals.[2] A version of the torito is designed to released candy when set off, which as the effect of having children run toward it, instead of running away. Toritos run about 800 pesos in the market.[8]

The most elaborate product is called a “piromusical” (pyro-musical) a set of fireworks synchronized to music and sometimes lights, with an average commercial price of about 10,000 pesos a minute, usually lasting about fourteen minutes.[8]

Tultepec

Most fireworks in Mexico are produced in the State of Mexico, especially the municipality of Tultepec just north of Mexico City, which has declared itself to be the “pyrotechnics capital of Mexico.”[9][10] This area has a two-hundred year tradition of making fireworks, with, about 65 percent of the population of the municipality is involved directly or indirectly in fireworks production.[4][8] In Tultepec, all fireworks are made by hand, including decoration and wrapping, mostly in small factories or workshops that produce everything from small firecrackers to twelve-inch shells for professional shows.[4][9] Tultepec is also one of the main suppliers of ingredients needed to make fireworks.[6]

Most fireworks production in the municipality is crowded into an area called the La Saucera pyrotechnic zone, located outside the town of Tultepec near the communities of Xahuento and Lomas.[5][8] Originally, all of the fireworks production was scattered around the municipality, but after the explosion and fire of fireworks stands at the La Merced Market in Mexico City in 1988, authorities decided to force artisans into one area away from residential areas and with security precautions such as special warehouses for finished products and to store chemicals.[8]

The State of Mexico’s largest fireworks market is located here as well, called the Mercado de San Pablito, constructed by the state which spent nine million pesos to construct 300 sturdy block stalls.[7][8] However, this market suffered major explosions in 2005 and 2006, reducing most of the stalls to rubble on both occasions. The market also has problems with regulations on how much they can store and sell in the market, as well as the harassment of customers leaving the market by police.[8] This has led to a fifty percent reduction in sales volume, with sales shifting to other, often clandestine, outlets in the municipality.[8]

The Feria Nacional de la Pirotecnia (National Pyrotechnics Festival) occurs each year in March in Tultepec, featuring a national competition of castillos.[5] Most attendance for the event is for the piromusicales competition, which draws about 10,000 spectators. There are also competitions for toritos and castillos.[11]

Danger

The industry is a dangerous one, mostly due to lack of enforcement of existing safety laws and regulation and lack of professional training.[8] A Tultepec mural shows townspeople, some lacking hands, lighting powder kegs and among castillos.[9] In the State of Mexico alone, there are about 500 artisans who make fireworks illegally, without the proper training or facilities and without permission from authorities. According to the Instituto Mexiquense de la Pirotecnia, the main reason for this is that their manufacture is mostly done in families, rather than in factories.[12] Most accidents have happened in Tultepec, with 46 explosions in the municipality in 2002 alone, with a total of twelve dead and dozens hurt.[2] In 2011, there were fourteen explosions in La Saucera, none of which were fatal, and one in a clandestine shop that left four people dead.[5]

There have been a number of notable accidents related to the manufacture and sale of fireworks in Mexico. In 1998, an explosion in a workshop in the Barrio de San Agustín neighborhood in Tultepec affected over one hundred houses and killed ten neighbors.[8] In 1999, an explosion in Celaya left 56 dead and 350 hurt.[2] In 2003, there was an explosion at the Miguel Hidalgo Market in Veracruz, which started at a clandestine fireworks warehouse that resulted in 28 dead, 35 hurt and 52 missing.[2] In 2006, an explosion at the San Pablito market was attributed to a product called a “cerillo” (match), which consists of a colored stick with chemicals on both ends which produces sparks when scraped on a surface. This led to a yearlong ban on the product so its safety could be reevaluated.[8] The last major accident in Tultepec was in 2016 when a major fireworks explosion in San Pablito killed at least 42.[13]

Sales

In Mexico, fireworks, especially large rockets called “cohetones” are a staple of patron-saint festivals.[9] Religious festivals even in the smallest towns have fireworks, which can include images of the patron saint on a frame outlined in pyrotechnics. This is particularly true to large pilgrimage sites such as that of Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos.[2] The biggest day for fireworks sales is Mexico’s independence day. For Mexico’s Bicentennial celebration at the Zocalo or main square in Mexico City, over 2,400 shells composed the multimedia spectacular which begins by a reenactment of Father Miguel Hidalgo’s call for troops at 11 pm September 15, 1810.[10]

There are three markets specializing in fireworks, San Pablito in Tultepec, one in Chimalhuacán and the other in Zumpango, with San Pablito being the most important in the country.[5][7]

National sales of fireworks fluctuates between 800,000 and 1,700,000 million pesos per year.[14] Only thirteen Mexican enterprises export abroad, mostly because they do not meet the standards for fireworks set by the United States, the closest major international market.[9][14] Mexican fireworks tend to be more powerful than mass-produced Chinese ones, which account for most of legal sales in the United States, which tempts many Americans to try and bring them across the border for Fourth of July celebrations.[9]

Mexican fireworks are mostly promoted by the State of Mexico’s Instituto Mexiquense de Pirotecnia, which sponsors events such as art exhibits with a pyrotechnic theme and puppet shows on fireworks safety for children.[15]

References

- ↑ "Juegos Pirotécnicos, cohetes y pólvora" [Pyrotechnic sets, rockets and powder] (in Spanish). Veracruz: Universidad Veracruzana. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "REPORTAJE /EL GRITO ENTRE FUEGOS" [Special report/The cry among fireworks]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. September 15, 2003. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Conti González Báez (July 15, 2006). "Los fuegos artificiales" [Fireworks]. Radio Red AM (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alicia Rivera (September 12, 2011). "Pirotecnia: El sustento de un pueblo" [Pyrotechics: The sustenance of a town]. Milenio Edomex (in Spanish). Toluca. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristian Villaseñor (February 8, 2012). "Artesanos pirotécnicos arriesgan la vida" [Pyrotechnic artisans risk their lives]. Hoy Estado de Mexico (in Spanish). Toluca. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Pirotecnia" [Pyrotechnics] (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Artesanos de Tultepec ganan concurso de pirotecnia en Alemania" [Artisans of Tultepec win pyrotechnics competition in Germany]. El Universal /Yahoo noticias (in Spanish). Mexico. September 28, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Silvia Chávez González (September 15, 2008). "Tultepec: artesanos de la pirotecnia buscan preservar una tradición de casi 200 años" [Tultepec: Pyrotechnic artisans look to preserve an almost 200-year-old tradition]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Chris Hawley (July 1, 2009). "Mexican fireworks pack too much pow". USA TODAY. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 "México recorre su Historia con fuegos artificiales a un paso del Bicentenario" [Mexico revisits its history with fireworks during its Bicentennial]. El Periodico de Mexico (in Spanish). Mexico City. September 18, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Reseña Feria nacional de la Pirotecnia 2012" [Overview of the Feria nacional de la Pirotecnia 2012] (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico. March 10, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Existen 500 artesanos de la pirotecnia irregulares en Edomex" [There are 500 unlicensed pyrotechnic artisans in the State of Mexico]. El Sol de Toluca (in Spanish). Toluca, Mexico. April 2, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Suman 32 muertes por explosión en Tultepec". El Universal. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- 1 2 "Juegos pirotécnicos hechos por manos mexiquenses se exportarán al país vecino del norte" [Pyrotechnic sets made by Mexican hands to be exported to neighboring country] (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico. April 25, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Héctor Ledezma (June 29, 2010). "Exponen pirotecnia en Neza" [Exhibit pyrotechnics in Ciudad Nezahuacoyotl]. El Universal (in Spanish). Toluca. Retrieved June 8, 2012.