Mewa Singh | |

|---|---|

ਮੇਵਾ ਸਿੰਘ | |

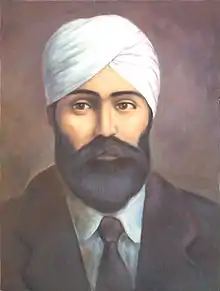

Portrait of Mewa Singh drawn by Sikh-Canadian artist Jarnail Singh | |

| Born | 1881 Lopoke, Punjab Province, British India |

| Died | January 11, 1915 (aged 33) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Organization | Khalsa Diwan Society Vancouver |

| Known for | Murder of W.C. Hopkinson |

| Movement | Ghadar Party |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse | Unmarried |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Mewa Singh Lopoke (Punjabi: ਮੇਵਾ ਸਿੰਘ ਲੋਪੋਕੇ) was a Sikh activist in Canada who was a member of the Vancouver branch of the Ghadar Party, which called for the overthrow of British rule in India. On October 21, 1914, Mewa Singh murdered a Canadian immigration inspector, W. C. Hopkinson, a political act of violence for which he was executed by the Canadian government.[1] In the eyes of Sikh Canadians, Mewa Singh's assassination of Hopkinson was a display of martyrdom, one which they commemorate annually.

Early life

Mewa Singh was born in 1881 in the village of Lopoke which is located in Ajnala Tehsil of Amritsar district in Punjab, India.[2] He was the son of Nand Singh Aulakh and had one brother who was named Dewa Singh.[2]

Vancouver, British Columbia

Similar to other migrants, Mewa Singh came to British Columbia, Canada in 1906 in search of a better livelihood.[3] Singh was one of over 5000 Punjabi men who arrived in Canada in the three years before 1908, the date when the Canadian government passed the Continuous Journey Regulation to prohibit further immigration from India.[3] Once Singh arrived, he joined the community of Punjabi labourers in British Columbia, finding employment working on the green chain of Fraser Mills in New Westminster near Vancouver.[2] Whilst living there, Mewa Singh came into contact with Sikh community leaders such as Bhag Singh Bhikhiwind and Balwant Singh Khurdpur of the Khalsa Diwan Society Vancouver.[2] In coordination with them, he became involved in the fundraising for the construction of the first Gurdwara, or Sikh temple, in Vancouver and North America.[2] After the inauguration of this first Gurdwara in January 1908, Mewa Singh was initiated as a Khalsa Sikh and he maintained an active role in the upkeep of the newly built Gurdwara.[3] In addition to this maintenance role, he also served as a granthi, or scripture reader.[3]

Ghadr Party involvement and first arrest

As a member of the small Punjabi community in Vancouver, Mewa Singh became familiar with people on both sides of the political barrier dividing local Sikhs.[4] On one side, there was the Ghadar Party activists, and on the other, a handful of informants reporting to W.C. Hopkinson and the Vancouver immigration department.[5] Through his connections with Balwant Singh, a fellow mill worker and granthi in the Vancouver Sikh Temple, and Bhag Singh, president of the Gurdwara management committee, Mewa Singh began working with the Ghadar Party.[6] Formed by Indians living in North America, the Ghadar Party was a movement founded in April 1913 that sought to undertake an armed struggle to gain India independence from British rule.[7] During the period of 1908–1918, Canadian immigration officials in Vancouver played an integral role in the surveillance of Indian nationalists in North America.[8] At the centre of this surveillance effort was W.C. Hopkinson, an immigration inspector, who established a network of moles within the city's nascent Punjabi community.[8] Hopkinson hired these informants to garner information about political activists who were perceived as a threat to British rule in India.[9]

In a statement made to Hopkinson in June 1914, an informant, Bela Singh Jian, reported that Mewa Singh, who was acting as a messenger, offered him $500 and a ticket to India or a piece of real estate in exchange for Jian stopping his collaboration with the immigration office.[10] A month later, on July 16, 1914, Mewa Singh joined three other Ghadarites – Bhag Singh, Balwant Singh, and Harnam Singh – who crossed the border at Sumas to meet Taraknath Das, a Bengali activist, and to purchase weapons to give to the passengers of the Komagata Maru.[6] At the time, the passengers had lost their case in the Appeal Court of British Columbia and had agreed to leave Canada.[11] However, the passengers refused to depart until the Canadian government had allocated provisions for their return across the Pacific.[11] While the ship was still in the harbour, three of the aforementioned men entered a hardware store in Sumas and purchased several firearms (two semi-automatic pistols and two revolvers) along with ammunition.[3] Shortly after, Mewa Singh, who had crossed the border ahead of his group, was apprehended by a provincial constable for avoiding the regular check point by attempting to go through the woods.[12] When he was arrested, Mewa Singh was found with two concealed revolvers and 300 rounds of ammunition.[12] The other members of the group were detained by American officials, but were eventually released two weeks later without charges against them.[12] As the only one arrested by Canadian authorities, Mewa Singh was facing up to ten years in prison on the charges of trafficking weapons and carrying concealed firearms.[3] He was approached by W.C. Hopkinson and immigration agent Malcolm Reid to provide evidence that would incriminate the other members of his party, and in turn, help build their case for Ghadar Party involvement with the Komagata Maru.[13] Ultimately, Mewa Singh complied, and in the statement he gave to Hopkinson and Reid, he acknowledged the following: (1) He went on the cross-border trip with the other men by chance and was never in their full confidence; (2) they purchased four revolvers; (3) Balwant Singh paid for the firearms; (4) and, according to his knowledge, the weapons were bought with the intent of convoying them to the Komagata Maru.[14] Although Hopkinson and Reid deemed his statement unsatisfactory, Mewa Singh was not considered a major player and was released on August 7, 1914, after paying a $50 fine with the help of the Vancouver Sikh Gurdwara.[3]

Murder of W.C. Hopkinson

Events preceding the murder

In the months following the return of the Komagata Maru to India in April 1914, the immigration officers in Vancouver faced backlash from the local Sikh community, whose members made headlines both as victims and as perpetrators.[15] During this time, Bela Singh Jian - one of W.C. Hopkinson's chief informants - became convinced that the Sikh Ghadarites in Vancouver would target him for being a spy within the community.[16] The sudden deaths of two other Immigration Department informants – Harnam Singh Gahal and Arjan Singh – seemed to confirm Bela Singh's suspicions.[16] On September 5, 1914, Bela Singh entered the Vancouver Gurdwara for the funeral of Arjan Singh.[16] In response to the perceived murder of his colleagues, and under abetment of Hopkinson, Bela Singh opened fire within the Gurdwara and murdered two Sikhs.[17] Bhag Singh Bhikhiwind, the president of the Gurdwara management committee and an anticolonial leader, was one of the two Sikhs that Bela Singh shot dead.[16] According to testimony from Balwant Singh, the presiding granthi at the time, Mewa Singh was at the Vancouver Gurdwara when the shooting occurred and was performing kirtan.[18]

After the shooting, Bela Singh called the police and was subsequently arrested. At the police station, Bela Singh claimed that he fired in self-defence. The other witnesses—who were friends of Bela Singh—corroborated his story.[19]

Shooting and arrest

On October 21, 1914, Bela Singh, charged with murder, was tried in the Provincial Court House of British Columbia.[17] His plan to plead self-defense hinged on proving that there had been prior threats against his life.[16] For this to work, he required testimony from Hopkinson, who could demonstrate that Bela Singh's life had been constantly threatened.[16] However, while Hopkinson was waiting by the courtroom door, he was approached by a group of Sikhs, which included Mewa Singh.[20] As they got closer, Mewa Singh marched up to Hopkinson, pulled out a revolver, and opened fire on him.[20] In total, Mewa Singh shot five bullets into Hopkinson's body.[16] After witnessing the shooting, several court employees surrounded Mewa Singh and demanded that he turn over his firearms.[21] Mewa Singh did not resist arrest, and as the head janitor stripped him of his weapons, he said “I shoot. I go to station."[21] As a result of Hopkinson's murder, Bela Singh's trial was immediately postponed, and the trial of Mewa Singh took its place.[22]

Murder trial and execution

As the historian Hugh M. Johnston writes, the speed at which the BC legal system processed the case of Mewa Singh had no precedent in modern Canada.[21] Mewa Singh's trial was held on October 21 and lasted only one hour and forty minutes. Without hesitation, Mewa Singh pleaded guilty and took absolute responsibility for the murder of W. C. Hopkinson. Furthermore, Mewa Singh claimed he had killed Hopkinson to defend the sanctity and honour of his religion, which had been desecrated by the shooting at the Vancouver Gurdwara. Singh argued that inspectors Hopkinson and Reid were behind Bela Singh's act of extreme violence. When questioned, Singh also spoke of his previous interactions with Hopkinson in his first arrest at the U.S. border in July, 1914. According to Singh, Hopkinson had pressured him to provide evidence to implicate the Shore Committee - a group of Vancouver Sikhs offering provisions and support to the Komagata Maru passengers. Additionally, Mewa Singh stated that Hopkinson tried to force him to testify in defence of Bela Singh earlier that month.[21] Mewa Singh's sentiments can be summed up in this excerpt from his translated court statement:

"You, as Christians, would you think there was any more good left in your church if you saw people shot down, and killed in it? You would not put up with it, because it would be bringing yourselves to a Nation that is dead, to tolerate such conduct, and it is better for a Sikh to die than to bring such disgrace and ill-treatment in the temple. It is far better to die than to live."[23]

At Mewa Singh's request, Edward Montague Woods, his court appointed lawyer, called no witnesses and conducted no cross-examination. Yet, Woods attempted to help Mewa Singh by appealing to the Minister of Justice in Ottawa, advocating for Mewa Singh's sentence to be commuted. Ultimately, Woods' efforts were futile and Mewa Singh's death sentence, the mandatory punishment for murder in Canada, was not commuted.[24]

On January 11, 1915, approximately 400 Sikhs gathered outside the New Westminster jail, where Mewa Singh was executed. After he was hanged, Mewa Singh's body was turned over to the crowd of Sikhs in attendance. From there, the procession of nearly 400 carried the body for three kilometres until they arrived at Fraser Mills, where they had received permission to cremate Mewa Singh's body.[25]

Aftermath

Neither the police nor the Vancouver Immigration officials believed that Mewa Singh acted alone. Although officials believed there to be a larger plan behind the murder, the Immigration Department was unable to make a compelling case to support these suspicions. However, officials still arrested several members of the Shore Committee (nearly all of them Ghadrite) with the charge of inciting Mewa Singh to murder Hopkinson. Later authorities dropped these charges for lack of evidence.[26]

A year after Mewa Singh was hanged, on January 11, 1916, he was acknowledged and eulogized in Ghadar Party literature. On the second anniversary, in 1917, Vancouver Sikhs congregated for several days at the Gurdwara by Fraser Mills, the location of Mewa Singh's cremation. In the following year, the number of Sikh attendees grew to five hundred, even though there were only about seven hundred Sikhs in BC.[27]

Contemporary memory and legacy

Annual commemoration

For the Sikh community of Vancouver, Mewa Singh is a martyr and his martyrdom is celebrated every year in the Khalsa Diwan Society's Gurdwara on Ross Street. Also, this occasion is marked and celebrated by other Sikh temples across Canada, and in the United States as well.[28] In Sikh circles, Mewa Singh is often referred to with the honorific title "Bhai" (or "brother"), which is accorded to those Sikhs who have distinguished themselves in their deeds for the community.

In 2015, the 100th anniversary of Mewa Singh's martyrdom was commemorated by the Prof. Mohan Singh Memorial Foundation. Taking place at the old British Columbia jail site in New Westminster at 7:45 AM - the same location and time of Mewa Singh's execution – members of the Sikh community paid tribute and respect to Mewa Singh for his sacrifice and contributions to the Ghadar Party.[29]

Bhai Mewa Singh Primary School

In 2019, SAF International, a Canadian NGO that provides aid to individuals across India, visited Mewa Singh's ancestral village of Lopoke. Upon seeing the village's primary school in such disrepair, SAF announced plans to rebuild and rename the primary school in his name.[30] The project, which is supported by the Gurdwara Sahib Sukh Sagar in British Columbia, Canada, began construction in early 2020. Once completed, the school will feature brand new SMART classrooms, a water reservoir, access to solar power, and a plaque that honours Mewa Singh's legacy and tells his story.

Calls for posthumous exoneration

Members of the Sikh community of Vancouver, such as Gurpreet Singh, the founder of the monthly magazine Radical Desi, have called upon the Canadian government to absolve Mewa Singh of criminal charges. A petition for this cause appeared on Change.org following Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's exoneration of six Chilcotin chiefs who were executed by the colonial government of Canada over 150 years ago. Gurpreet Singh, who started the petition, argues that Mewa Singh's murder of W.C. Hopkinson was a political act of aggression that was in response to the wider institutional racism against South Asian immigrants in Canada.[31] Similarly, at the centenary of Mewa Singh's martyrdom, Sahib Singh Thind, the president of the Prof. Mohan Singh Memorial foundation, called for Mewa Singh's name to be disassociated from any criminal connection within the legal system of Canada and the relevant historical literature.[29]

The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson

Written and directed by Paneet Singh, The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson, is a play that was put on in the Vancouver Art Gallery as part of the 2018 Monsoon Festival of Performing Arts.[32] It was the first major artistic and theatrical production to revisit and re-envision the assassination of W.C. Hopkinson and the trial of Mewa Singh. As playwright Paneet Singh explained, The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson is a forum that seeks to insert Mewa Singh's story into the mainstream by recounting the events that led to the shooting, and the social conditions that made his martyrdom inevitable. Importantly, the play was performed at the same venue where the original trial took place on October 21, 1914.[33]

External links

References

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (Summer 1988). "The Surveillance of Indian Nationalists in North America". BC Studies. 78: 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pooni, Sohan Singh (2009). Canada De Gadri Yodhe (in Punjabi). Amritsar: Singh Brothers. p. 71. ISBN 978-8172054267.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Johnston, Hugh (1998). "SINGH, MEWA". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. 14.

- ↑ "MEWA SINGH, LOPOKE (C. 1881-1915)". Komagata Journey: Continuing the Journey. SFU Library. 2012.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (Summer 1988). "The Surveillance of Indian Nationalists in North America". BC Studies. 78: 9–15.

- 1 2 Pooni, Sohan Singh (2009). Canada De Gadri Yodhe. Amritsar: Singh Brothers. p. 72.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (Summer 2013). "The Komagata Maru and the Ghadr Party: past and present aspects of a historic challenge to Canada's exclusion of immigrants from India". BC Studies (178): 9.

- 1 2 Johnston, Hugh (Summer 1988). "The Surveillance of Indian Nationalists in North America". BC Studies. 78: 4.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (Summer 1988). "The Surveillance of Indian Nationalists in North America". BC Studies. 78: 3–4.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Force: The Police Repulsed". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 111.

- 1 2 Johnston, Hugh (Summer 2013). "THE KOMAGATA MARU AND THE GHADR PARTY: Past and Present Aspects of a Historic Challenge to Canada's Exclusion of Immigrants from India". BC Studies (178): 23.

- 1 2 3 Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Force: The Police Repulsed". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 119.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (Summer 2013). "THE KOMAGATA MARU AND THE GHADR PARTY: Past and Present Aspects of a Historic Challenge to Canada's Exclusion of Immigrants from India". BC Studies (178): 23–24.

- ↑ Singh, Mewa (August 1914). "Statement of Mewa Singh, son of Nand Singh, Village of Lopoke, District of Amritsar, India". City of Vancouver Archives: 2.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An End and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 192.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sohi, Seema (2014). "Imperial Immigration Policy, Citizenship, and Ships of Revolution". Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance, and Indian Anticolonialism in North America. Oxford Scholarship Online. pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 Pooni, Sohan Singh (2009). Canada de Gadri Yodhe. Amritsar: Singh Brothers. p. 73.

- ↑ McKelvie, Bruce Alistair (1966). Magic, Murder and Mystery. Cowichan Leader Ltd. p. 58.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 195.

- 1 2 Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 197.

- ↑ Sohi, Seema (2014). "Imperial Immigration Policy, Citizenship, and Ships of Revolution". Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance, and Indian Anticolonialism in North America. Oxford Scholarship Online. p. 146.

- ↑ "MEWA SINGH, LOPOKE (C. 1881-1915)". Komagata Maru: Continuing the Journey. SFU Library. 2012.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 200.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 198.

- ↑ Johnston, Hugh (2014). "Assassination: An Ending and a Beginning". The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 203.

- ↑ Kalsi, Seva Singh (2005). "Cultural Expressions". Religions of the World: Sikhism. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 86.

- 1 2 Mall, Rattan (January 12, 2015). "100th "martyrdom" anniversary of Mewa Singh commemorated by Prof. Mohan Singh Memorial Foundation of Canada". Indo-Canadian Voice.

- ↑ "Bhai Mewa Singh Punjab School".

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (April 1, 2018). "Gurpreet Singh: Now it's time for Canada to exonerate Mewa Singh for a century-old murder in Vancouver". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver Free Press.

- ↑ "THE UNDOCUMENTED TRIAL OF WILLIAM C. HOPKINSON". Monsoon Festival of Performing Arts. 2018.

- ↑ Mann, Jagdeesh (May 16, 2018). "Vancouver play highlights Canada's forgotten martyr Mewa Singh". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc.