Maurice Joostens | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Joostens published in the French review La Revue Diplomatique in 1904 | |

| Belgian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to China and Siam | |

| In office 8 May 1900 – 22 January 1901 | |

| Preceded by | Carl de Vinck de Deux-Orp |

| Succeeded by | Emile de Cartier de Marchienne (as chargé d'affaires) |

| In office 1 November 1903 – 17 April 1904 | |

| Preceded by | Emile de Cartier de Marchienne (as chargé d'affaires) |

| Succeeded by | Edmond de Gaiffier d'Hestroy |

| Belgian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Spain | |

| In office 1 July 1904 – 21 July 1910 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 September 1862 Berchem, Antwerp, Belgium |

| Died | 21 July 1910 (aged 47) Antwerp, Belgium |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Edmond Constantin Joostens Mathilde Josephine Pauline De Boe |

| Education | University of Paris Catholic University of Leuven Free University of Brussels |

| Occupation | Diplomat |

Baron Adolphe Marie Maurice Joostens (23 September 1862 – 21 July 1910), was a Belgian diplomat. As a signatory of the Boxer Protocol, the final act at the Algeciras Conference and the Colonial Charter in which Congo Free State was ceded to Belgium, Joostens was an important Belgian diplomat in the age of New Imperialism. Throughout his career, Joostens was able to gain the absolute confidence of king Leopold II of Belgium and eventually he became one of the monarch's favourite diplomats.

Background

Maurice Joostens was born in one of the richest and most prominent families of the Belgian city of Antwerp. The wealth and influence of the Joostens family had, according to the legend, their origins in a lucky investment that Mathias Joostens had made during the age of Napoleon Bonaparte. He accidentally put an extra '0' on an order and bought 5,000 instead of 500 bales of coffee. Because of inflation during the Continental Blockade he suddenly had a fortune in his hands and was no longer a modest merchant. This story even inspired Hendrik Conscience to fictionalize this anecdote and write the book Eene 0 te veel. The family was subsequently able to rise among the ranks of the Antwerp bourgeoisie and Maurice Joostens his grandfather Constantin Joostens became a senator for the Belgian Liberal Party.[1] Besides from the influence and capital of his family Joostens had also other assets to become a diplomat. His trip to Egypt with his influential uncle Arthur Van Den Nest in 1882 and Joostens orientalist report Du Caire au Tropique are for example prime examples of his fascination for foreign countries.[2][3] In the meantime Joostens had completed his studies at the University of Paris, the University of Leuven and the Université libre de Bruxelles and he obtained his degree in arts. Before he pursued a career in the diplomacy, Joostens shortly followed in the footsteps of his father being active in the Antwerp banking scene where he had a job at the Handelsbank.[4]

Diplomatic career

Early career

On 7 December 1885, Joostens filed his request at the Belgian ministry for foreign affairs to become a so-called attaché de légation and this was the start of his diplomatic career. First, he was, from April 1886 until January 1889, the second-class secretary at the legation in Madrid, then headed by Edouard Anspach, the brother of Jules Anspach. In 1889, Joostens made promotion to the legation in Cairo, where he served the Belgian imperial interests of, for example, Édouard Empain and the Tramways d'Alexandrie.[5] Shortly after his displacement to Egypt, Joostens was again promoted. This time he became first-class secretary in the highly ranked legation in London. There he could further develop his diplomatic skills both on the European and the imperial diplomatic theatre.

Washington D.C.

As a result of an internal reorganisation in the Belgian diplomatic corps, Joostens was able to further develop his career. The new minister for foreign affairs Paul de Favereau promoted him in 1896 to Washington D.C. where he would be the new conseiller de la légation or advisor of the legation. Under the auspices of Gontran de Lichtervelde Joostens showed remarkable diplomatic skill. In 1898 the Belgian the then prince Albert of Belgium made a visit to the United States together with his physician L. Melis and Harry Jungbluth. For this occasion Joostens was named the diplomatic attaché to this group. This was because of the commercial and imperialist agenda of this voyage, not only was Alberts visit a way for the future king to learn the country better, his uncle Leopold II of Belgium saw in this trip a great opportunity to tighten the Belgian-American relations on the imperialistic scene. By order of Leopold II, Joostens used the allure of the royal visit to attract investors for a Belgian-American cooperation to build the Beijing–Hankou Railway. It was in this context that Joostens had several contacts with the American senator Calvin S. Brice who to Joostens his great regret died during the American-Belgian negotiations. Although he didn't succeed to forge a cooperation between the American China Development Company and the Belgian investments backed by Leopold II, Joostens was able to show his feel for the diplomatic game in this episode and obtain the appreciation of the king.[6] Next to the royal visit of prince Albert and the Beijing-Hankou Railway, the remarkable plan to make the Philippines a Belgian protectorate after the Spanish–American War was a third case in which Joostens was active.[7]

The Hague

During his holidays in Belgium recovering from an uninterrupted three years stay in the United States, Joostens was named secretary for the Belgian delegation for the Hague Peace Conference of 1899. This conference was an initiative of the Russian Tsar Nicolas II and is one of the prime examples of pacifism in the eve of the First World War. During this conference Joostens could gain more experience in the field of international relations under the guidance of delegation leader and well-known disarmament advocate Auguste Beernaert. The latter would even win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1909 for his presence at The Hague Conventions.[8]

Beijing

Arrival

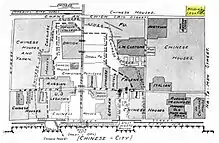

Only fourteen years after his first application to the Belgian ministry of foreign affairs, Joostens was promoted in the winter of 1899 to the rank of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary at the court of the Chinese emperor and the king of Siam. When Joostens arrived in Beijing to replace baron Carl de Vinck de Deux-Orp, he ended up in the Legation Quarter where all the foreign legations were situated and in which there was a very distinctive diplomatic culture with its own practices and rules.[9] In this context, Joostens could rely on a competent team of Belgian lower-ranking diplomats and officials. The most remarkable members of the Belgian legation in this time were, for example, Alphonse Splingaerd, son of the Belgian Mandarin Paul Splingaerd, Leopold Merghelynck, Adrien de Mélotte de Lavaux, who would become director of the Sino-Belgian Bank in Shanghai, and Emile de Cartier de Marchienne, who would become the Belgian ambassador to both China.[10]

Boxer Rebellion and the Siege of the International Legations

Shortly after Joostens' arrival, the Boxer Rebellion, of which the first features showed in the winter of 1899, would reach its peak. This rebellion had anti-foreign, anti-Christian and mystical features and had among other things its origins in a crop failure in 1899, decades of frustrations about the Western presence in China and the chaos and internal struggles at the Chinese court following the failed Hundred Days' Reform. The wrath of the rebels was first aimed at Chinese Christians but later faced towards the foreign presence in China.[11][12] Since the Belgians were not unlike the other foreign investments deemed unwanted elements in the Chinese society, the Beijing-Hankou Railway was also attacked and several Belgian engineers, missionaries and officials were killed.[13] During the first quarrels in the streets of the Legation Quarters Joostens was accused of having killed several rebels, but since the Austro-Hungarian government offered to protect the Belgian legation, it is more likely that these soldiers have fired these shots. After the assassination of the German envoy Klemens von Ketteler near the Belgian legation and the refusal of the foreign diplomats to leave the Legation Quarter after Empress Dowager Cixi ordered them to do so, the rebellion reached a turning point. From now on, the Chinese Empire was at war with the foreign countries, and in this context, Joostens had to defend from 13 June until 16 June 1900, together with the other Belgians and the Austro-Hungarian marines, the Belgian legation. Despite their efforts, they were not able to repel the rebels and had to retreat to first the French and later the British legation. In the meantime, the Belgian legation, which was located in an isolated corner in the Legation Quarter, was plundered and set on fire. On 20 June 1901, the rebels sieged, in collaboration with Imperial Chinese Army, the Legation Quarter and with this act the so-called Siege of the International Legations was put in place. Shortly after the rebels sieged the Legation Quarter, the foreign powers gathered their forces and formed the Eight-Nation Alliance to crush the rebellion manu militari. Leopold II had also been very keen to participate and even privately funded a Belgian Expeditionary Corps but Kaiser Wilhelm II strongly opposed this idea and the king had to give up this plan.[14]

Conference of Peking

When Beijing (Peking) was relieved on 14 August 1901 by the Eight-Nation Alliance, the Boxer Rebellion came to an end, but this meant by no means the end of instability in China. Nevertheless, both the foreign powers ( France, Germany, Japan, United States, United Kingdom, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Belgium, The Netherlands and Spain) and the pro-foreign officials at the Chinese court such as Li Hongzhang and Yikuang (Prince Qing) wanted to reach a settlement over the Chinese responsibility in the rebellion. The negotiations that took place in this context, between 26 October 1900 and 7 September 1901, are known as the Conference of Peking and they would among other things focus on the indemnities on the one hand and the punishment of the leaders of the rebellion on the other hand. Although Ernest Mason Satow and Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein, respectively the British and German envoy, preferred from the start on that only the members of the Eight-Nation Alliance settled these matters, Joostens succeeded to conquer his place at the negotiation table. He was able to do so thanks to his active role since the first meeting on 26 October 1900 and the support of French envoy Stephen Pichon.[15][16]

From then on, Joostens nevertheless was not able to have strong voice. This was a result of the small state position of Belgium because of the lack of military input in the Eight-Nation Alliance, a reflection of the quite unimportant status of Belgium in Europe and the omnipresent influence of his minister for foreign affairs Paul de Favereau. Although Joostens was not seen as one of the most important envoys present, the lack of cooperation between the different nations offered the possibility to have a certain influence. The Belgian envoy was for example the chairman of the Committee on the Indemnities and inspired by the losses of the Societé d’Étude de chemins de fer en Chine, the Belgian company behind the Beijing-Hankou Railway, he proposed to include also indirect losses of companies and societies in the indemnity claims. Next to that, Joostens also persuaded his colleagues to lower the proposed embargo on the trade and production of arms to a span of only two years and by doing so, he favoured the interests of FN Herstal and the Belgian arms factories in general. The most important contribution of Joostens from a Belgian perspective was his role in the compilation of the Belgian indemnities. Cooperating very closely with Paul de Favereau Joostens was active in almost every aspect of this task. He verified the indemnity claims, he communicated and negotiated with the French envoys Paul Beau and Stephen Pichon about the indemnities of Beijing-Hankou Railway and questioned the claims of other countries in order to safeguard the payment of the Belgian claims.[15]

Other projects in which Joostens was involved were, for example, the plan to invite Zaifeng, Prince Chun for a visit to Belgium. Since the prince proposed this visit himself, he accepted the offer but when he was in Germany to convey his regrets to the Kaiser Empress Dowager Cixi became ill and the prince had to cancel the rest of his trip to Europe. Joostens was also very active to claim the right to install the Belgian Legation Guard in Beijing. Belgian boots on Chinese soil offered in Joostens' eyes a big potential, but since the Belgian Legation Guard only consisted of about 20 soldiers, the guard can't possibly be seen as the fulfillment of Leopold II his military ambitions in China. Joostens diplomacy during the Conference is at best summarized as an execution of the orders of his minister Paul de Favereau with the addition of personal initiatives within a typical Leopoldistic imperial mindset.[15]

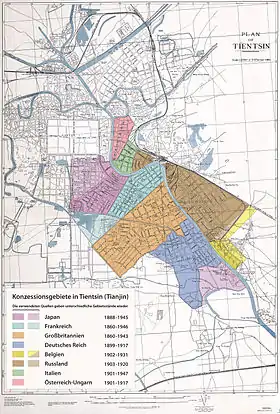

Other activities

In the margin of the Conference of Peking, Joostens was also active in other cases. In cooperation with Henri Ketels, the consul in Tianjin, Joostens succeeded to claim a Belgian concession in Tianjin. Despite the failed development of this concession because of a lack of interest from Belgian investors, Joostens succeeded to obtain this parcel despite the criticism of the other powers. Besides from this territorial achievement, Joostens also kept playing his role in the cases of finances and more specifically the indemnities. Even after the signature of the Boxer Protocol, the payment of the indemnities was still an unsolved problem and in this context Joostens tried to convince his government not to found a Belgian bank. In Joostens' opinion the Chinese indemnities for Belgium could also be paid to a foreign bank and subsequently be transferred to an already existing Belgian bank in Europe. Nevertheless, the Belgian government did found a Sino-Belgian Bank. A third important aspect of Joostens' diplomacy in China aimed at protecting the Belgian missionaries. Although the Belgian missionaries officially were French citizens as a result of the French Protectorate in China, Joostens repeatedly defended the rights of the missionaries of Belgian origin. He checked reports of attacks on Belgian manned missions and urged the Chinese government to repel the attacks of what used to be Boxer rebels. Finally Joostens also acted as a spokesman of the Belgian imperial lobby. Both in China and Belgium, he promoted several times the Belgian project. On several occasions Joostens highlighted for example the prospects of an investment in China and tried to convince investors and ordinary people to come to China and work in Belgian companies or invest in them. Despite the efforts of Joostens and other Belgian officials the Belgian presence would never be able to match the success of the pre-war era. The Boxer Rebellion had showed that an investment in China could be risky and from 1901 onwards the interest of Belgian investors further diminished.[14][15]

Aftermath

Thanks to fact that Joostens was one of the diplomats who were sieged in the summer of 1900, the Belgian envoy became a prominent and well-known figure not only within diplomatic circles, but also within the public sphere. Whereas stories like these were not available in the European press before, the development of the press as a mass medium throughout the nineteenth century had made possible that the messages concerning the Siege of the International Legations reached big audiences in the western world. Where diplomats were often depicted as lazy, money spoiling and useless bureaucrats, the siege had pointed out the dangers and usefulness of the job.[17] Nevertheless, the coverage of Joostens in Belgian and international press was quite one-sided and although some media covered also the diplomatic work of the Belgian envoy, the main focus was put on his role during the siege. Joostens remarkable performance at the Conference of Peking did not pass unnoticed at the Belgian royal court. In 1904 Leopold II gave Joostens the hereditary title of baron as a final reward for his time in Beijing.[15]

This focus on his own person enabled Joostens to use this attention to put the Belgian expansion on the agenda of the Belgian economic scene as pointed out before. On the other hand, the attention for Joostens also played a great part in the awareness of the Belgian presence in China and raised the tangibility of the project for a great deal of people who had never heard of the activities of the Belgian missionaries, Belgian investors and Belgian diplomats before. Finally the different receptions, dinners and ceremonies celebrating Joostens' return to Belgium tightened to bonds within the Belgian imperialist lobby. Since diplomats usually hided behind the curtains of diplomacy Joostens' public performance is very noteworthy.[15][18]

Although Joostens' residence in Beijing was undoubtedly the most important and notable time in his career, it had also its side-effects. Because of the harsh living conditions in Beijing, Joostens unstable health fastly declined and in 1904 an emotionally and physically weak Joostens finally got the displacement he had been asking for since 1902. Being appointed as the envoy in Madrid Joostens was for the first time in his career promoted to be the highest-ranking official in a legation of a traditional European power. Since the living conditions in such a wealthy city were far better than in Beijing the promotion took Joostens wishes into account.[15]

During his stay in Beijing Joostens also supervised the construction of a new Belgian legation building, erected on grounds within the Legation Quarter that were granted to Belgium following the Boxer Protocol (the former building, located outside the Quarter proper, had been demolished during the 1900 siege). The new location was previously occupied by the residence of Xu Tong, Grand Secretary of the Tiren Cabinet, who committed suicide in 1900.[19] The new building, still extant today, was designed by Louis Delacenserie in 1902 and features a Flemish Gothic Revival architecture.[20]

Madrid

The first years of Joostens' stay in Spain were characterized by a focus on the improvement of the Belgian-Spanish economic relations. Joostens was for example very active in the preparations of the Spanish pavilion at the world's fair in Liège in 1905.[21] During his Spanish years, Joostens would also be again in the center of the imperialist world theater. Spain was after all an important imperial power and the neighbourhood of Morocco posed both a lot of opportunities and problems. Joostens was first active in the Belgian imperialist penetration of Morocco through the establishment of Belgian companies in the country.[22] Following the First Moroccan Crisis Joostens was appointed by Leopold II to attend the Algeciras Conference together with Conrad de Buisseret. The international meeting was installed to figure out a solution for the German contestation of the growing French and Spanish control over Morocco. Leopold II told Joostens that he was not allowed to gain any profits for Belgium at the conference and Joostens loyally followed these orders.

End of career

As showed before Joostens was as a Belgian envoy in Madrid still very active in the imperialist schemes of Leopold II. The king even appointed him during his yearly holidays in Belgium as a member of the diplomatic team that had to negotiate the transfer of Congo Free State to Belgium. After the Congo Free State propaganda war led by Edmund Dene Morel had pointed out the atrocities in the king's private country in Africa, Leopold II could no longer resist or repel the criticism and he prepared to hand the Congo over to the Belgian state. In this context Joostens was one of the architects of the Colonial Charter that settled this matter.

Joostens' role in this transition from a royal Belgian colonial empire towards a Belgian state-led colonialism would be his last achievement of importance. In his last years in the legation in Madrid, Joostens' health would further decline. When on a leave to recover in Belgium in 1910, Joostens died on 21 July, Belgium's national holiday, suffering from a heart stroke despite the fact that his sister Alice had been taking care of him for several weeks.

Honours

Belgium

- 1931 : Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown.[23]

_Ribbon_bar.svg.png.webp) Knight of the Order of Leopold (1898)

Knight of the Order of Leopold (1898) Officer of the Order of Leopold (1900)

Officer of the Order of Leopold (1900) Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown

Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown Hereditary title of Belgian baron. (1904)

Hereditary title of Belgian baron. (1904)

Foreign

Spain

Knight of the Order of Charles III (1887)

Knight of the Order of Charles III (1887) Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (1890)

Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (1890)

Ottoman Empire

Commander of the Order of Osmanieh (1890)

Commander of the Order of Osmanieh (1890) Grand Officer of the Order of Medjidie (1891)

Grand Officer of the Order of Medjidie (1891)

Chinese Empire

First Class Third Grade of the Order of the Double Dragon (1903)

First Class Third Grade of the Order of the Double Dragon (1903)

Norway

Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav (1907)

Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav (1907)

References

- ↑ Geerts, G. (1980). "Eene "0" te veel'". Polderheem. 15: 13–16.

- ↑ "Maurice Joostens, Du Caire au Tropique". L'Afrique Explorée et Civilisée. 7: 278–279. 1886.

- ↑ Joostens, M. (1885). Du Caire au Tropique. Brussels.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Van Lichtervelde, B. (1955). "Joostens (Adolphe Marie Maurice)". Biographie Coloniale Belge. No. Tome IV. pp. 448–450.

- ↑ Rahimlou, Y. (1988). "Aspects de l'expansion belge en Egypte sous le régime d'occupation britannique (1882–1914)'". Civilisations. 38: 101–178.

- ↑ Luyckx, J. (2007). For business, pleasure and education. De reis van prins Albert naar de Verenigde Staten in 1898. unpublished master's thesis, KU Leuven, Faculty of Arts, Department of History. pp. 17–57.

- ↑ Blumberg, A. (1972). "Belgium and a Philippine protectorate: a stillborn plan". Asian Studies. 10: 340.

- ↑ Eeyffinger, A.; Kooijmans, P. H. (1999). The 1899 Hague Peace Conference: "The Parliament of Man, the Federation of the World. Den Haag. pp. 133–136.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Moser, M. J.; Moser, Y. W.-C. (1993). Foreigners within the Gates: The Legations at Peking. Hong Kong and New York. ISBN 978-0-19-585702-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Spae, J. (1986). Mandarijn Paul Splingaerd. Brussel. p. 162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Xiang, L. (2003). The Origins of the Boxer War: A Multinational Study. London and New York. pp. 120–206.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Cohen, P. A. (1997). History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York. pp. 14–56.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Brosens, G. (2003). De commerciële ruggengraat van China gebroken. De Boksersaanval op de Belgische spoorwegconcessie Peking-Hankow in 1900. Unpublished master's thesis, Universiteit Gent, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Department of History.

- 1 2 Kurgan-Van Hentenryck, G. (1972). Léopold II et les groupes financiers belges en Chine: la politique royale et ses prolongements (1895–1914). Brussel. p. passim.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Huskens, G (2016). Maurice Joostens en het Bokserprotocol. Marionet op het diplomatieke theater?. Unpublished master's thesis, KU Leuven, Faculty of Arts, Department of History.

- ↑ Kelly, J. S. (1963). A forgotten conference: the negotiations at Peking, 1900–1901. Genève.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Auwers, M. (2014). The island and the storm: a social-cultural history of the Belgian diplomatic corps in times of democratization, 1885–1935. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Department of History. pp. 210–251.

- ↑ Viaene, V. (2008). "'King Leopold's Imperialism and the Origins of the Belgian Colonial Party, 1860–1905'". The Journal of Modern History. 80 (4): 741–790. doi:10.1086/591110. S2CID 144513498.

- ↑ Chu, Chia Chen (1944). Diplomatic Quarter in Peiping. University of Ottawa. p. 108.

- ↑ "Chronique du jour". Gazette de Charleroi. Charleroi. 1902-09-11. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ↑ "Liège 1905 – Section Internationale – Halls". Worldfairs.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Duchesne, A. (1965). Léopold II et le Maroc (1885–1906). Brussel. pp. 222–239.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ RD 26.12.1931

Further reading

- Auwers, M. (2014). The island and the storm : a social-cultural history of the Belgian diplomatic corps in times of democratization, 1885–1935, Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Department of History.

- Bickers, R.A. en Tiedemann, R.G. (2007). The Boxers, China, and the World. Lanham.

- Cohen, P. (1997). History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth, New York.

- Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, G., (1972). Léopold II et les groupes financiers belges en Chine: la politique royale et ses prolongements (1895–1914), Brussels.

- Coolsaet, R. (2014). België en zijn buitenlandse politiek 1830–2015, Leuven.

- De Lichtervelde, B. (1955). ‘Joostens (Adolphe-Marie-Maurice)’, Biographie Coloniale Belge, IV, Brussel, 448–450.

- Duchesne, A (1950). "La dissolution de la legion belge en Chine, 1900". Carnet de la Fourragère. 3: 193–216.

- Duchesne, A (1948). "'Quand les Belges devaient partir pour la Chine. Un projet d'expedition contre les Boxeurs, 1900'". Carnet de la Fourragère. 1: 1–45.

- Elliott, J. E. (2002). Some Did It for Civilisation, Some Did It for Their Country: A Revised View of the Boxer War, Hong Kong.

- Frochisse, J.-.M. (1936). La Belgique et la Chine, Relations diplomatiques et economiques (1839–1909), Brussels.

- Huskens, G. (2016). Maurice Joostens en het Bokserprotocol. Marionet op het diplomatieke theater?, Unpublished master's thesis, KU Leuven, Faculty of Arts, Department of History.

- Kelly, J. S. (1963). A forgotten conference: the negotiations at Peking, 1900–1901, Genève.

- Luyckx, J. (2007). For business, pleasure and education. De reis van prins Albert naar de Verenigde Staten in 1898, Unpublished master's thesis, KU Leuven, Faculty of Arts, Department of History.

- Luyckx, J. (2013). "Prins Albert op verkenning in Noord-Amerika (1898). Het merkwaardige reisdagboek van een toekomstig Belgisch staatshoofd". Handelingen van de Koninklijke Commissie voor Geschiedenis / Bulletin de la Commission Royale d'Histoire. 179: 297–358.

- Otte, T. G. (2002). "Not Proficient in Table-Thumping: Sir Ernest Satow at Peking, 1900–1906". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 13 (2): 161–200. doi:10.1080/714000310. S2CID 155895249.

- Otte, T. G. (2007). The China Question: Great Power Rivalry and British Isolation, 1894-1905. Oxford.

- Van den Eede, M. (2006). De Belgische mondiale expansie (1831-1914). Een systematisch onderzoek naar de determinanten, actoren en evolutie van de Belgische koloniale en de financieel-industriële expansie, vanaf Leopold I tot de eerste wereldoorlog, Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universiteit Gent, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Department of History.

- Viaene, V. (2008), ‘King Leopold’s Imperialism and the Origins of the Belgian Colonial Party, 1860–1905’, The Journal of Modern History, 80, 741–790.

- Xiang, L. (2003). The Origins of the Boxer War: A Multinational Study, Londen and New York.