| Matthew 1:10 | |

|---|---|

← 1:9 1:11 → | |

Michelangelo's Hezekiah-Manasseh-Amon. Traditionally Manasseh is the man on the right and Amon is the child on the left. | |

| Book | Gospel of Matthew |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

Matthew 1:10 is the tenth verse of the first chapter in the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible. The verse is part of the section where the genealogy of Joseph, the father of Jesus, is listed.

Content

In the King James Version of the Bible the text reads:

The World English Bible translates the passage as:

- Hezekiah became the father of Manasseh.

- Manasseh became the father of Amon.

- Amon became the father of Josiah.[1]

Analysis

This part of the list coincides with the list of the Kings of Judah in a number of other parts of the Bible. Unlike other parts of Matthew's genealogy this list is fully in keeping with the other sources. According to William F. Albright, Hezekiah ruled from 715 BC to 687 BC. His son Manasseh ruled from his father's death until 642 BC, while Manasseh's son Amon ruled from 642 BC to 640 BC. Josiah ruled from 640 BC to 609 BC.[2] Manasseh was widely regarded as the most wicked king of Judah, so why he appears in this genealogy when other discreditable ancestors have been left out is an important question. W. D. Davies and Dale Allison note that the portrayal of Manasseh in the literature of the period was divided. While some sources represented him as a purely wicked figure, others represented him as man who eventually found repentance for his deeds. The author of Matthew may have been more acquainted with the later school and thus left him in.[3]

The biblical scholar Robert H. Gundry points out that the author of Matthew actually wrote Amos, rather than Amon. He argues the name might have been changed to link the minor prophet Amos who made predictions concerning the messiah.[4]

Archaeology

There are extra-biblical sources that specify Hezekiah by name, along with his reign and influence, that "[h]istoriographically, his reign is noteworthy for the convergence of a variety of biblical sources and diverse extrabiblical evidence often bearing on the same events. Significant data concerning Hezekiah appear in the Deuteronomistic History, the Chronicler, Isaiah, Assyrian annals and reliefs, Israelite epigraphy, and, increasingly, stratigraphy".[5] Hezekiah's story is one of the best to cross-reference with the rest of the Mid Eastern world's historical documents.

In 2015 in a dig at the Ophel in Jerusalem, Eilat Mazar discovered a royal bulla of Hezekiah, that reads "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah", and dates to between 727 - 698 BC.[6][7][8] This is the first seal impression of an Israelite or Judean king to come to light in a scientific archaeological excavation.[9][10] The impression on this inscription was set in ancient Hebrew script.[11]

A lintel inscription, found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to his secretary, Shebnah (2 Kings 18:18). LMLK stored jars along the border with Assyria "demonstrate careful preparations to counter Sennacherib's likely route of invasion" and show "a notable degree of royal control of towns and cities which would facilitate Hezekiah's destruction of rural sacrificial sites and his centralization of worship in Jerusalem".[5] Evidence suggests they were used throughout his 29-year reign (Grena, 2004, p. 338). There are some Bullae from sealed documents that may have belonged to Hezekiah himself (Grena, 2004, p. 26, Figs. 9 and 10). There are also some that name his servants (ah-vah-deem in Hebrew, ayin-bet-dalet-yod-mem).

Archaeological findings like the Hezekiah seal led scholars to surmise that the ancient Judahite kingdom had a highly developed administrative system.[12] The reign of Hezekiah saw a notable increase in the power of the Judean state. At this time Judah was the strongest nation on the Assyrian-Egyptian frontier.[13] There were increases in literacy and in the production of literary works. The massive construction of the Broad Wall was made during his reign, the city was enlarged to accommodate a large influx, and population increased in Jerusalem up to 25,000, "five times the population under Solomon,"[5] Archaeologist Amihai Mazar explains, "Jerusalem was a virtual city-state where the majority of the state's population was concentrated," in comparison to the rest of Judah's cities (167).[14]

The Siloam Tunnel was chiseled through 533 meters (1,750 feet) of solid rock[15] in order to provide Jerusalem underground access to the waters of the Gihon Spring or Siloam Pool, which lay outside the city. The Siloam Inscription from the Siloam Tunnel is now in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. It "commemorates the dramatic moment when the two original teams of tunnelers, digging with picks from opposite ends of the tunnel, met each other" (564).[15] It is "[o]ne of the most important ancient Hebrew inscriptions ever discovered."[15] Finkelstein and Mazar cite this tunnel as an example of Jerusalem's impressive state-level power at the time.

Archaeologists like William G. Dever have pointed at archaeological evidence for the iconoclasm during the period of Hezekiah's reign. The central cult room of the temple at Arad (a royal Judean fortress) was deliberately and carefully dismantled, "with the altars and massebot" concealed "beneath a Str. 8 plaster floor". This stratum correlates with the late 8th century; Dever concludes that "the deliberate dismantling of the temple and its replacement by another structure in the days of Hezekiah is an archeological fact. I see no reason for skepticism here."[16]

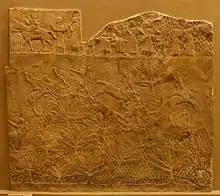

During the revolt of king Hezekiah against Assyria, city of Lachish was captured by Sennacherib despite determined resistance (see Siege of Lachish). As the Lachish relief attests, Sennacherib began his siege of the city of Lachish in 701 BC.[17] The Lachish Relief graphically depicts the battle, and the defeat of the city, including Assyrian archers marching up a ramp and Judahites pierced through on mounted stakes. "The reliefs on these slabs" discovered in the Assyrian palace at Nineveh "originally formed a single, continuous work, measuring 8 feet ... tall by 80 feet ... long, which wrapped around the room" (559).[15] Visitors "would have been impressed not only by the magnitude of the artwork itself but also by the magnificent strength of the Assyrian war machine."[15]

.JPG.webp)

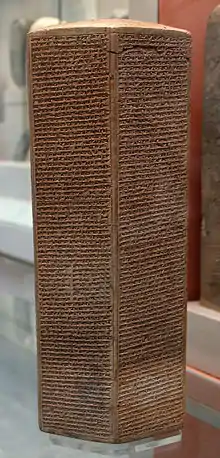

Sennacherib's Prism was found buried in the foundations of the Nineveh palace. It was written in cuneiform, the Mesopotamian form of writing of the day. The prism records the conquest of 46 strong towns [18] and "uncountable smaller places," along with the siege of Jerusalem during Hezekiah's reign where Sennacherib says he just "shut him up...like a bird in a cage,"[15] subsequently enforcing a larger tribute upon him.

The Hebrew Bible states that during the night, the angel of Jehovah (YHWH Hebrew) brought death to 185,000 Assyrians troops (2 Kings 19:35), forcing the army to abandon the siege, yet it also records a tribute paid to Sennacherib of 300 silver talents following the siege. There is no account of the supernatural event in the prism. Sennacherib's account records his levying of a tribute from Hezekiah, the king of Judea, who was within Jerusalem, leaving the city as the only one intact following the exile of the northern ten-tribe kingdom of Israel due to idolatry. (2 Kings 17:22,23; 2 Kings 18:1–8) Sennacherib recorded a payment of 800 silver talents, which suggests a capitulation to end the siege. However, Inscriptions have been discovered describing Sennacherib's defeat of the Ethiopian forces. These say: “As to Hezekiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke, I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities . . . and conquered (them) . . . Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage.” (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p. 288) He does not claim to have captured the city. This is consistent with the Bible account of Hezekiah's revolt against Assyria in the sense that neither account seems to indicate that Sennacherib ever entered or formally captured the city. Sennacherib in this inscription claims that Hezekiah paid for tribute 800 talents of silver, in contrast with the Bible's 300, however this could be due to boastful exaggeration which was not uncommon amongst kings of the period. Furthermore, the annals record a list of booty sent from Jerusalem to Nineveh.[19] In the inscription, Sennacherib claims that Hezekiah accepted servitude, and some theorize that Hezekiah remained on his throne as a vassal ruler.[20] The campaign is recorded with differences in the Assyrian records and in the biblical Books of Kings; there is agreement that the Assyrian have a propensity for exaggeration.[15][21]

One theory that takes the biblical view posits that a defeat was caused by "possibly an outbreak of the bubonic plague".[22] Another that this is a composite text which makes use of a 'legendary motif' analogous to that of the Exodus story.[23]

A signet ring has been found in the City of David in Jerusalem featuring the name of one of King Josiah's officials, Nathan-Melech, mentioned in the book of 2 Kings 23:11. The inscription of the ring says, "(belonging) to Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King."[24] Though it may not directly mention King Josiah by name, it does appear to be from the same time period in which he would have lived. Seals and seal impressions from the period show a transition from those of an earlier period which bear images of stars and the moon, to seals that carry only names, a possible indication of Josiah's enforcement of monotheism.[25]

The date of Josiah's death can be established fairly accurately. The Babylonian Chronicle dates the battle at Harran between the Assyrians and their Egyptian allies against the Babylonians from Tammuz (July–August) to Elul (August–September) 609 BCE. On that basis, Josiah was killed by the army of Pharaoh Necho II in the month of Tammuz (July–August) 609 BCE, when the Egyptians were on their way to Harran.[26]

In other literature

In rabbinic literature and Christian pseudepigrapha Manasseh is accused of executing the prophet Isaiah; according to Rabbinic Literature Isaiah was the maternal grandfather of Manasseh.[27]

The Prayer of Manasseh, a penitential prayer attributed to Manasseh, appears in some Christian Bibles, but is considered apocryphal by Jews, Roman Catholics and Protestants.

References

- ↑ BibleHub Matthew 1:10

- ↑ Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- ↑ Davies, W.D. and Dale C. Allison, Jr. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Edinburgh : T. & T. Clark, 1988-1997.

- ↑ Gundry, Robert H. Matthew a Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1982.

- 1 2 3 "Hezekiah." The Anchor Bible Dictionary. 1992. Print.

- ↑ Eisenbud, Daniel K. (2015). "First Ever Seal Impression of an Israelite or Judean King Exposed near Temple Mount". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ↑ ben Zion, Ilan (2 December 2015). ""לחזקיהו [בן] אחז מלך יהדה" "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah"". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Heilpern, Will (3 December 2015). "King Hezekiah's seal discovered in Jerusalem - CNN". CNN. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ "Impression of King Hezekiah's Royal Seal Discovered in Ophel Excavations South of Temple Mount in Jerusalem | האוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים | The Hebrew University of Jerusalem". new.huji.ac.il. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ↑ "First ever seal impression of an Israelite or Judean king exposed near Temple Mount".

- ↑ Alyssa Navarro, Archaeologists Find Biblical-Era Seal Of King Hezekiah In Jerusalem "Tech Times" December 6

- ↑ Fridman, Julia (14 March 2018). "Hezekiah Seal Proves Ancient Jerusalem Was a Major Judahite Capital". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Na'aman, Nadav. Ancient Israel and Its Neighbors, Eisenbrauns, 2005, ISBN 978-1-57506-108-5

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel and Amihai Mazar. The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel. Leiden: Brill, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Archaeological Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005. Print.

- ↑ Dever, William G. (2005) Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel (Eerdmans), pp. 174, 175.

- ↑ "Hezekiah." The Family Bible Encyclopedia. 1972. Print.

- ↑ James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965) 287–288.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 110.

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 314.

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 308-309.

- ↑ Zondervan Handbook to the Bible. Grand Rapids: Lion Publishing, 1999. p. 303

- ↑ Sweeney, Marvin Alan (1996). Isaiah 1–39: With an Introduction to Prophetic Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 476. ISBN 9780802841001.

- ↑ Borschel-Dan, Amanda. "Tiny First Temple find could be first proof of aide to biblical King Josiah". The Times of Israel. The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86912-4.

- ↑ Thiele, Mysterious Numbers 182, 184–185.

- ↑ ""Hezekiah". Jewish Encyclopedia". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. 1906.

Sources

- Grabbe, Lester (2003). Like a Bird in a Cage: The Invasion of Sennacherib in 701 BCE. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826462152.

- Grayson, A.K. (1991). "Assyria: Sennacherib and Essarhaddon". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521227179.

- Thiele, Edwin, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257, 217.

| Preceded by Matthew 1:9 |

Gospel of Matthew Chapter 1 |

Succeeded by Matthew 1:11 |