Marion Coates Hansen | |

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 June 1870[1] Osbaldwick, Yorkshire[2] |

| Died | 2 January 1947 (aged 75) Great Ayton, Yorkshire |

| Political party | Independent Labour Party Women's Social and Political Union Women's Freedom League |

| Spouse | Frederick Hansen |

Marion Coates Hansen (née Coates; 3 June 1870 – 2 January 1947) was an English feminist and women's suffrage campaigner, an early member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a founder member of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) in 1907. She is generally credited with having influenced George Lansbury, the Labour politician and future party leader, to take up the cause of votes for women when she acted as his agent in the general election campaign of 1906. Lansbury became one of the strongest advocates for the women's cause in the pre-1914 era.

Hansen spent her almost her whole life in Middlesbrough, and was an active member of the local Independent Labour Party (ILP). Born into the well-to-do Coates family, she was drawn to socialism through her association with Joseph Fels, the American industrialist and social reformer for whom she worked as a nanny in Philadelphia in the early 1890s. She was one of a group who left the WSPU in protest against the increasingly autocratic attitudes of Emmeline Pankhurst and her family towards the organisation's general membership. After the First World War she took up local politics in Middlesbrough, became a local councillor in Middlesbrough, and was involved in housing reform and slum clearance. Her contributions to the cause of women's rights has largely been overlooked by historians, who have tended to concentrate on higher profile figures.

Early life

Little information has been published about Hansen's early life, education and upbringing. She was born Marion Coates in 1870 or 1871, in Osbaldwick, Yorkshire. While she was still a young child, the family moved to the Linthorpe district of Middlesbrough.[3] Among her siblings were two older brothers: Charles and Walter, who became successful businessmen, and were associated with the American industrialist and social reformer Joseph Fels.[4][5] Through the Fels connection Hansen travelled to Philadelphia, probably in the late 1880s or early 1890s, where she worked for a time as a nanny in the Fels household.[6]

During her American sojourn Hansen discovered and was inspired by the poetry and democratic philosophy of Walt Whitman.[6] On her return to England she became an active proponent of socialism and women's rights, using the pages of the radical socialist journal Justice to attack the standard Victorian male prejudices concerning the roles of women in society.[7] When one leading socialist opined that women ought to be "captivated and charmed by the beauties and possibilities of socialism", Hansen wrote a condemnatory reply in Justice magazine: "We women are not going to be bought like goodies ... We are coming as comrades, friends, warriors to a state worthy of us, not to dolldom".[8] Around 1900 she married Frederick Hansen, a member of a well-to-do Middlesbrough family with socialistic beliefs. The Hansen and the Coates families were influential members of the local Independent Labour Party (ILP), in which Marion Hansen, as branch secretary, was the driving force; she, her family and their associates were known in local socialist circles as "the Linthorpe set". From time to time this group's influence and their paternalistic attitudes, in particular their permanent control over the branch's executive committee, caused resentment among the more working class membership. Another point of contention was the conflict of interest between Hansen's ILP duties and her growing interest in the politics of feminism.[6] In 1903, when the Women's Social and Political Union was founded to promote the cause of women's suffrage, Hansen became an early member.[9]

Suffragist

Background

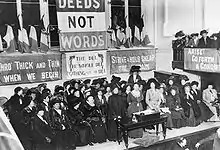

The WPSU, founded in 1903, was a breakaway movement from the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) which, led by Millicent Fawcett, promoted the cause of women's suffrage by gradualist, law-abiding methods.[10] Certain NUWSS members, led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her family, wanted a more active strategy and a more specific goal: to secure voting rights for women on the same basis as for men.[11] They founded the WPSU with the motto "Deeds not Words", and the new body began to build an activist membership.[12] Initially, the WPSU did not promote the kinds of disruptive actions which later became its hallmark; the change in tactic occurred in 1905, when it appeared that reform via the parliamentary route was doomed to failure. In February 1905 the Liberal opposition MP, Bamford Slack, introduced a bill to the House of Commons, which would give votes to women in parliamentary elections. When the bill was debated on 12 May, it was "talked out" by its opponents and was not put to the vote. Sensing that the Liberals would soon become the governing party, the WSPU sought assurances from the party's spokesmen that they would, when in power, legislate on votes for women. The failure of the Liberal leadership to give this commitment led to the adoption by the WSPU of more aggressive tactics.[13] From the autumn onwards Liberal party meetings were regularly heckled and harassed; Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were imprisoned after disrupting a meeting in Manchester, obstructing the police and refusing to pay the fine.[14]

Association with George Lansbury

Hansen's first recorded contribution to the WSPU cause came in September 1905. Anticipating that a general election would be held in the near future, she secured the candidacy of the socialist activist George Lansbury in the Middlesbrough constituency, on a programme that included a specific commitment to votes for women.[6] Lansbury was a local councillor and Poor Law guardian in Poplar, a tireless worker among the poor and disadvantaged of the East End of London.[15] He became known to Hansen through the Coates family's connection with Joseph Fels, who had worked with Lansbury in the organisation of work schemes to assist the unemployed. In 1889 Lansbury had acted as agent for Jane Cobden when she was elected to the London County Council,[16] and was known to Emmeline Pankhurst who had campaigned for him at Walworth during the 1895 general election.[17] Since the Cobden election, Lansbury's priorities had shifted to poverty and unemployment.[18]

Because the local ILP was bound by a secret election pact with the Liberals to support the Liberal candidate, Joseph Havelock Wilson, they could not endorse Lansbury. Hansen tried without success to bypass this restriction. She wrote to Ramsay MacDonald, the secretary of the Labour Representation Committee, pointing out the advantages for the Labour movement in supporting a candidate such as Lansbury, but MacDonald was unable to help; Lansbury stood as an independent socialist. Hansen persuaded Lansbury to include in his election address not only a commitment to women's enfranchisement but other radical socialist policies: Irish Home Rule, state pensions, full employment and trade union recognition. Her close involvement with Lansbury's campaign—she acted as his agent—angered some in her local party, but she fulfilled her duties with calm efficiency; according to Shepherd she "displayed the essential quality of any agent ... to maintain optimism in all situations, whatever the daunting difficulties". Her husband Frederick acted as campaign treasurer, and most of costs was borne by Fels and Walter Coates. Nevertheless, when the election came in January 1906, Lansbury's socialist brew proved too much for what his biographer John Shepherd describes as "the mainly working-class, all-male electorate", and Lansbury was heavily defeated. Wilson received 9,227 votes, his Conservative opponent 6,846 and Lansbury 1,484—less than 9 percent of the total vote.[19]

Hansen was primarily responsible in introducing Lansbury to and educating him in the issue of women's suffrage, a fact that he acknowledged when writing to her in October 1912. Shepherd writes that in due course, "gender was to replace social class at the head of his concerns and preoccupations" and votes for women became for him the overwhelming question of the day.[20] After Lansbury finally entered parliament in 1910 he expressed to Hansen his lack of faith in the ability of his fellow-Labour MPs to secure women's enfranchisement, despite the party by then having a formal policy commitment. In 1912 Lansbury resigned his parliamentary seat—against Hansen's passionate pleas against such action—to fight for it on the single issue of votes for women;[21] Hansen was devastated when he lost the ensuing by-election: "a more unhappy time I have never lived through".[22] In August 1913 Lansbury was imprisoned for incitement, after publicly supporting the militant tactics of the suffragist bodies which had by then passed well beyond the threshold of lawfulness. Although he was quickly released, Hansen wrote to him with approval: "You have done a big thing for us. It ... shows how far in the dark ages we still are, especially in matters concerning the welfare of women".[23]

Hansen's concerns for Lansbury extended to his family, especially to his wife Bessie with whom she formed a warm and lasting friendship. She felt that Bessie needed a break from her responsibilities for her large family, and invited her to stay in Middlesbrough for a holiday: "The boys can look after the [younger] children, the girls can cook dinner and Mr Lansbury can darn his socks".[24]

WSPU activist

In the year following the January 1906 general election, won by the Liberals with a large majority, the WSPU was active in a number of by-election contests. Hansen took part in several of these campaigns. At Cockermouth in August 1906, a divergence of view arose within the WSPU over whether Robert Smillie, the ILP candidate, should be supported. Smillie favoured women's suffrage in a general way, but was not a declared supporter; he shared with most Labour MPs the view that trade union reforms should take precedence over women's issues. Christabel Pankhurst and others decided on a separate campaign against all three declared candidates, and accordingly arranged rival meetings. This created difficulties for those such as Hansen and Mary Gawthorpe, who had strong ILP loyalties.[25] Although Gawthorpe spoke on behalf of Smillie, Hansen followed Christabel's line, a course of action that further antagonised her local ILP and caused her temporary resignation from the secretaryship.[6]

In her memoirs written many years later, the suffragist Hannah Mitchell provides a number of glimpses of Hansen during the 1906–10 period. Mitchell remembers her campaigning during a by-election at Huddersfield in November; a little later, while leading a series of meetings, Mitchell caught a chill: "I became so ill that my hostess, Mrs Coates-Hanson [sic], put me to bed at once ... Thanks to her kindness I managed to get through all the meetings, and she insisted on my staying a few days to rest. The Hanson home was lovely, and it was the first time in my life I had ever been waited on, and nursed, while the beautiful courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Hanson to each other, and to their guests, made those few days like a glimpse of Paradise".[26]

The WSPU continued to grow rapidly, but many members were become increasingly dissatisfied by the organisation's lack of democracy and its detachment from the Labour movement. The historian Martin Pugh remarks that to many, "[the WSPU] represented no more than a small central coterie that took little notice of its members' opinions".[27] When in September 1907 Emmeline Pankhurst abandoned the constitution and appointed an executive committee of her own nominees a number of members, including Hansen, left the WSPU and formed the Women's Freedom League (WFL). The WFL, while fully committed to the activist struggle, adopted a democratic constitution. It collected many of the WSPU's working class members and promoted better relations with the Labour movement in parliament.[28] Hansen, together with Charlotte Despard and Teresa Billington-Greig joined the WFL's initial executive committee.[29]

Women's Freedom League

Despite her role in the formation of the WFL, there are few records of Hansen's activities on its behalf, although her correspondence with Lansbury in the years up to 1914 indicates that she remained passionately committed to the cause of women's suffrage. She may have been one of the WFL members who attempted to petition King Edward VII at the State Opening of Parliament on 29 January 1908, and may have participated in the mass pickets of the House of Commons and 10 Downing Street, organised by the WFL in the summer of 1909.[29] Hansen's future sister-in-law Alice Schofield (she married Charles Coates in 1910) had greater visibility; an active WFL organiser, she was imprisoned in 1909 for her part in a demonstration at the House of Commons.[9] Although the two women shared common political and ideological concerns, they were not close; Alice Coates's daughter Marion Johnson, interviewed in 1975, revealed that the two disliked each other, and where possible kept their distance.[5]

Later life

After the First World War, during which the women's suffrage campaign was largely suspended, Hansen does not appear to have resumed her WFL activities. In 1919 she and Alice Coates became the first women elected to Middlesbrough Borough Council–Coates was elected a week before Hansen. The two were among the very few active suffragists who took up local politics.[30] Hansen's main concerns as a councillor were related to slum clearance and housing; during the 1930s she spoke against the indiscriminate destruction of properties in the historic district of St Hilda's, maintaining that many houses scheduled for demolition "possessed fine elevations and interiors which make fault finding a difficult task".[31]

From 1911 Hansen, who was childless, lived with her husband in the Nunthorpe district of the town.[32] Later, after Frederick Hansen's death, Hansen lived in Great Ayton, outside Middlesbrough, where she died on 2 January 1947.[33] Shepherd quotes Lansbury's description of Hansen as "a very slightly built woman: her frail body possesses an iron will and a courageous spirit. The freedom for which she strove was one which would emancipate body, soul and spirit".[34] Shepherd also remarks on Hansen's relative invisibility after her active life was over: "[H}er name is rarely even mentioned in the standard histories of the suffragette movement".[6] the local history society at Nunthorpe refers to her as "an extraordinary feminist whom historians have forgotten".[32]

See also

References

- ↑ Marion Coates-Hansen in Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934

- ↑ 1901 England Census

- ↑ "All 1881 UK Census Collection results for Marion Coates". ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 61 and p. 84

- 1 2 "Johnson, Mrs Marion". The Women's Library. 12 April 1975. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shepherd 2002, pp. 84–85

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 39

- ↑ Hunt, p. 201

- 1 2 Crawford, p. 130

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 118

- ↑ Purvis, June (January 2011). "Pankhurst (née Goulden), Emmeline". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35376. Retrieved 6 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ↑ "Women and the Vote: Start of the suffragette movement". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ Purvis 2002, pp. 72–75

- ↑ Purvis, June (January 2011). "Pankhurst, Dame Christabel Harriette". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35375. Retrieved 8 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ↑ Shepherd, John (January 2011). "Lansbury, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34407. Retrieved 2 February 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ↑ Scheer, pp. 71–75

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 45

- ↑ Scheer, p. 87

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, pp. 86–88

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 89 and p. 121

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, pp. 121–22

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 128

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, p. 133

- ↑ Shepherd 2002, pp. 352–53

- ↑ Rosen, pp. 69–71

- ↑ Mitchell, p. 35 and pp. 88–89

- ↑ Pugh, p. 144

- ↑ Pugh, pp. 163–67

- 1 2 Crawford, pp. 721–22

- ↑ "Challenge and Change: A Brief History of Women Councillors in Yorkshire & the Humber" (PDF). Center for Women & Democracy. 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Delplanque, Paul (11 June 2010). "Over the Border". gazettelive.co.uk. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Famous people of Nunthorpe". Nunthorpe History Group. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Name of deceased (surname first)" (PDF). The London Gazette: 3038. 1 July 1947.

- ↑ Shepherd, pp. 117–18

Sources

- Crawford, Dorothy (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23926-5.

- Hunt, Karen (1996). Equivocal Feminists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55451-9.

- Mitchell, Hannah (1968). The Hard Way Up. London: Faber. OCLC 461064.

- Pugh, Martin (2008). The Pankhursts. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-52043-6.

- Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: a biography. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23978-8.

- Rosen, Andrew (2013). Rise Up, Women!. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-62384-1. (First published by Routledge in 1974)

- Scheer, Jonathan (1990). George Lansbury: Lives of the Left. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-2170-7.

- Shepherd, John (2002). George Lansbury: at the Heart of Old Labour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-198-20164-8.