Luxor

الأقصر ⲡⲁⲡⲉ ⲡϣⲟⲙⲧ ⲛ̀ⲕⲁⲥⲧⲣⲟⲛ | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Luxor Temple, Ramses II, Abu Haggag Mosque, Crocodile Island Resort, feluccas on the Nile | |

Flag | |

| Nickname: City of Palaces | |

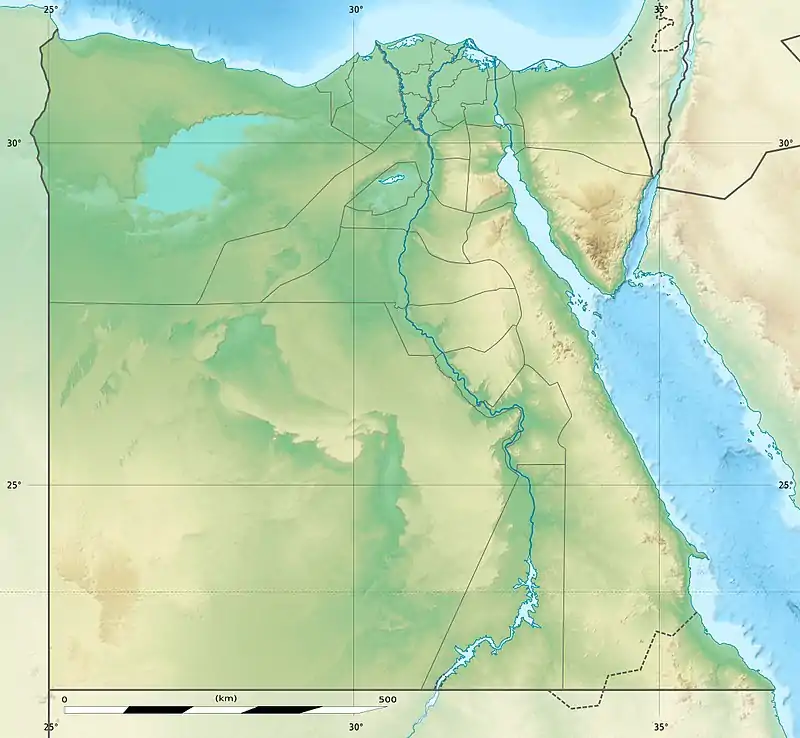

Luxor Location of Luxor within Egypt  Luxor Luxor (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 25°41′48″N 32°38′40″E / 25.69667°N 32.64444°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Luxor |

| Area | |

| • Total | 417 km2 (161 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 89 m (292 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 1,333,309 |

| • Density | 3,200/km2 (8,300/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Luxorian |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| Area code | (+20) 95 |

| Website | www |

Luxor (Arabic: الأقصر, romanized: al-ʾuqṣur, lit. 'the palaces') is a city in Upper Egypt, which includes the site of the Ancient Egyptian city of Thebes. Luxor had a population of 1,333,309 in 2020,[2] with an area of approximately 417 km2 (161 sq mi)[1] and is the capital of the Luxor Governorate. It is among the oldest inhabited cities in the world.

Luxor has frequently been characterized as the "world's greatest open-air museum", as the ruins of the Egyptian temple complexes at Karnak and Luxor stand within the modern city. Immediately opposite, across the River Nile, lie the monuments, temples and tombs of the west bank Theban Necropolis, which includes the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. Thousands of tourists from all around the world arrive annually to visit Luxor's monuments, contributing greatly to the economy of the modern city. Yusuf Abu al-Haggag is the patron saint of Luxor.

Etymology

The name Luxor (Arabic: الأقصر, romanized: al-ʾuqṣur, lit. 'the palaces', pronounced /ˈlʌksɔːr, ˈlʊk-/,[3] Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [ˈloʔsˤoɾ], Upper Egyptian: [ˈloɡsˤor]) derives from the Arabic qasr (قصر), meaning "castle" or "palace".[4][5][lower-alpha 1] It may be equivalent to the Greek and Coptic toponym τὰ Τρία Κάστρα ta tria kastra and ⲡϣⲟⲙⲧ ⲛ̀ⲕⲁⲥⲧⲣⲟⲛ pshomt enkastron respectively, which both mean "three castles".[7])

The Sahidic Coptic name Pape (Coptic: ⲡⲁⲡⲉ, pronounced Coptic pronunciation: [ˈpapə]),[7] comes from Demotic Ỉp.t "the adyton", which, in turn, is derived from the Egyptian. The Greek forms Ἀπις and Ὠφιεῖον come from the same source.[7] The Egyptian village Aba al-Waqf (Arabic: أبا الوقف, Ancient Greek: Ωφις) shares the same etymology.[8]

The Greek name is Thebes (Ancient Greek: Θῆβαι) or Diospolis. The Egyptian name of the city is Waset, also known as Nut (Coptic: ⲛⲏ)[9]

and

History

Luxor was the ancient city of Thebes, the capital of Upper Egypt during the New Kingdom, and the city of Amun, later to become the god Amun-Ra. The city was regarded in the ancient Egyptian texts as wAs.t (approximate pronunciation: "Waset"), which meant "city of the sceptre", and later in Demotic Egyptian as ta jpt (conventionally pronounced as "tA ipt" and meaning "the shrine/temple", referring to the jpt-swt, the temple now known by its Arabic name Karnak, meaning "fortified village"), which the ancient Greeks adapted as Thebai and the Romans after them as Thebae. Thebes was also known as "the city of the 100 gates", sometimes being called "southern Heliopolis" ('Iunu-shemaa' in Ancient Egyptian), to distinguish it from the city of Iunu or Heliopolis, the main place of worship for the god Ra in the north. It was also often referred to as niw.t, which simply means "city", and was one of only three cities in Egypt for which this noun was used (the other two were Memphis and Heliopolis); it was also called niw.t rst, "southern city", as the southernmost of them.

The importance of the city started as early as the 11th Dynasty, when the town grew into a thriving city.[10] Montuhotep II, who united Egypt after the troubles of the First Intermediate Period, brought stability to the lands as the city grew in stature. The Pharaohs of the New Kingdom in their expeditions to Kush, in today's northern Sudan, and to the lands of Canaan, Phoenicia and Syria saw the city accumulate great wealth and rose to prominence, even on a world scale.[10] Thebes played a major role in expelling the invading forces of the Hyksos from Upper Egypt, and from the time of the 18th Dynasty to the 20th Dynasty, the city had risen as the political, religious and military capital of Ancient Egypt.

The city attracted peoples such as the Babylonians, the Mitanni, the Hittites of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), the Canaanites of Ugarit, the Phoenicians of Byblos and Tyre, the Minoans from the island of Crete.[10] A Hittite prince from Anatolia even came to marry with the widow of Tutankhamun, Ankhesenamun.[10] The political and military importance of the city, however, faded during the Late Period, with Thebes being replaced as political capital by several cities in Northern Egypt, such as Bubastis, Sais and finally Alexandria.

However, as the city of the god Amun-Ra, Thebes remained the religious capital of Egypt until the Greek period.[10] The main god of the city was Amun, who was worshipped together with his wife, the Goddess Mut, and their son Khonsu, the God of the moon. With the rise of Thebes as the foremost city of Egypt, the local god Amun rose in importance as well and became linked to the sun god Ra, thus creating the new 'king of gods' Amun-Ra. His great temple at Karnak, just north of Thebes, was the most important temple of Egypt right until the end of antiquity.

Later, the city was attacked by Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal who installed a new prince on the throne, Psamtik I.[10] The city of Thebes was in ruins and fell in significance. However, Alexander the Great did arrive at the temple of Amun, where the statue of the god was transferred from Karnak during the Opet Festival, the great religious feast.[10] Thebes remained a site of spirituality up to the Christian era, and attracted numerous Christian monks of the Roman Empire who established monasteries amidst several ancient monuments including the temple of Hatshepsut, now called Deir el-Bahri ("the northern monastery").[10]

Following the Muslim conquest of Egypt, part of the Luxor Temple was converted from a church to a mosque. This mosque is currently known as the Abu Haggag Mosque today.

The 18th century saw an increase of Europeans visiting Luxor, with some publishing their travels and documenting its surroundings, such as Claude Sicard, Granger, Frederick Louis Norden, Richard Pococke, Vivant Denon and others. By the 20th century, Luxor had become a major tourist destination.

Archaeology

.jpg.webp)

In April 2018, the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities announced the discovery of the shrine of god Osiris- Ptah Neb, dating back to the 25th dynasty in the Temple of Karnak. According to archaeologist Essam Nagy, the material remains from the area contained clay pots, the lower part of a sitting statue and part of a stone panel showing an offering table filled with a sheep and a goose which were the symbols of the god Amun.[11][12][13]

On the same day in November 2018, two different discoveries were announced. One was by the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities that had found a 13th-century tomb on the West Bank belonging to Thaw-Irkhet-If, the overseer of the mummification shrine at the temple of Mut, and his wife.[14] Five months of excavation work until this point had revealed colorful scenes of the family and 1,000 funerary statues or ushabti.[14] The other discovery was of 1000 ushabti and two sarcophagi each containing a mummy in the TT33 complex by a joint team from the IFAO (French Institute of Oriental Archaeology, Cairo, Egypt) and the University of Strasbourg.[14][15] One of the sarcophagi was opened in private by Egyptian antiquities officials, while the other, of a female 18th Dynasty woman named Thuya, was opened in front of international media.[14][16][17]

In October 2019, Egyptian archaeologists headed by Zahi Hawass revealed an ancient "industrial area" used to manufacture decorative artefacts, furniture and pottery for royal tombs. The site contained a big kiln to fire ceramics and 30 ateliers. According to Zahi Hawass, each atelier had a different aim – some of them were used to make pottery, others used to produce gold artefacts and others still to churn out furniture. About 75 meters below the valley, several items believed to have adorned wooden royal coffins, such as inlaid beads, silver rings and gold foil were unearthed. Some artefacts depicted the wings of deity Horus.[18][19]

In October 2019, the Egyptian archaeological mission unearthed thirty well-preserved wooden coffins (3,000 years old) in front of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in El-Assasif Cemetery. The coffins contained mummies of twenty-three adult males, five adult females and two children, who are believed to be from the middle class. According to Hawass, mummies were decorated with mixed carvings and designs, including scenes from Egyptian gods, hieroglyphs, and the Book of the Dead, a series of spells that allowed the soul to navigate in the afterlife. Some of the coffins had the names of the dead engraved on them.[20][21][22][23]

On the 8th of April 2021, Egyptian archaeologists led by Zahi Hawass found Aten, a 3,400-year-old "lost golden city" near Luxor. It is the largest known city from Ancient Egypt to be unearthed to date. The site was said by Betsy Bryan, professor of Egyptology at Johns Hopkins University to be "the second most important archaeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamen".[24] The site is celebrated by the unearthing crew for showing a glimpse into the ordinary lives of living ancient Egyptians whereas past archaeological discoveries were from tombs and other burial sites. Many artefacts are found alongside the buildings such as pottery dated back to the reign of Amenhotep III, rings and everyday working tools. The site is not completely unearthed as of the 10th of April 2021.[24]

Landmarks

West bank

|

East bank |

|

Geography

Climate

Luxor has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) like the rest of Egypt. Aswan and Luxor have the hottest summer days of any other city in Egypt. Aswan and Luxor have nearly the same climate. Luxor is one of the sunniest and driest cities in the world. Average high temperatures are above 40 °C (104 °F) during summer (June, July, August). During the coolest month of the year, average high temperatures remain above 22 °C (71.6 °F) while average low temperatures remain above 5 °C (41 °F).

The climate of Luxor has precipitation levels lower than even most other places in the Sahara, with less than 1 mm (0.04 in) of average annual precipitation. The desert city is one of the driest ones in the world, and rainfall does not occur every year. The air in Luxor is more humid than Aswan but still very dry. There is an average relative humidity of 39.9%, with a maximum mean of 57% during winter and a minimum mean of 27% during summer.

The climate of Luxor is extremely clear, bright and sunny year-round, in all seasons, with a low seasonal variation, with about some 4,000 hours of annual sunshine, very close to the maximum theoretical sunshine duration.

In addition, Luxor, Minya, Sohag, Qena and Asyut have the widest difference of temperatures between days and nights of any city in Egypt, with almost 16 °C (29 °F) difference.

The hottest temperature recorded was on May 15, 1991, which was 50 °C (122 °F) and the coldest temperature was on February 6, 1989, which was −1 °C (30 °F).[25]

| Climate data for Luxor, 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.9 (91.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

42.2 (108.0) |

46.2 (115.2) |

50.0 (122.0) |

48.5 (119.3) |

47.8 (118.0) |

47.0 (116.6) |

46.0 (114.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

38.2 (100.8) |

34.8 (94.6) |

50.0 (122.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

41.2 (106.2) |

41.4 (106.5) |

41.2 (106.2) |

39.3 (102.7) |

35.5 (95.9) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

33.6 (92.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 2.8 (0.11) |

0.4 (0.02) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.8 (0.03) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.5 (0.02) |

1.1 (0.04) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

8.3 (0.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 55 | 47 | 39 | 31 | 29 | 27 | 30 | 33 | 37 | 43 | 51 | 57 | 39.9 |

| Source: NOAA (humidity 1961–1990)[26][27] | |||||||||||||

Coptic Catholic Eparchy

The Coptic Catholic (Alexandrian Rite) minority established on November 26, 1895 an Eparchy (Eastern Catholic Diocese) of Luqsor (Luxor) alias Thebes, on territory split off from the Apostolic Vicariate of Egypt. Its episcopal see is a St. George cathedral in Luxor.

In turn, it lost territory on August 10, 1947 to establish the Eparchy of Assiut and again on 14 September 1981 to establish Sohag.

Suffragan Eparchs of Luxor

- Ignazio Gladès Berzi (March 6, 1896 – died January 29, 1925)

- Marc Khouzam (August 6, 1926 – August 10, 1947), also Apostolic Administrator of Alexandria of the Copts (Egypt) (December 30, 1927 – August 10, 1947); later Coptic Catholic Patriarch of Alexandria (10 August 10, 1947 – died February 2, 1958)

- Isaac Ghattas (June 21, 1949 – May 8, 1967), later Archbishop-Bishop of Minya of the Copts (Egypt) (May 8, 1967 – died June 8, 1977)

- Amba Andraos Ghattas, Lazarists (C.M.) (May 8, 1967 – June 9, 1986), also Apostolic Administrator of Alexandria of the Copts (Egypt) (February 24, 1984 – June 9, 1986), President of Synod of the Catholic Coptic Church (1985 – March 30, 2006), President of Assembly of the Catholic Hierarchy of Egypt (1985 – March 30, 2006), later Coptic Catholic Patriarch of Alexandria (June 23, 1986 – retired March 30, 2006), created Cardinal-Patriarch (February 21, 2001 – died January 20, 2009), also President of Council of Catholic Patriarchs of the East (2003–2006)

- Aghnatios Elias Yaacoub, Jesuits (S.J.) (July 15, 1986 – died March 12, 1994), previously Coadjutor Eparch of Assiut of the Copts (Egypt) (May 19, 1983 – July 15, 1986)

- Youhannes Ezzat Zakaria Badir (June 24, 1994 – December 27, 2015), previously Eparch (Bishop) of Ismayliah of the Copts (Egypt) (November 23, 1992 – June 23, 1994)

- Emmanuel (Khaled Ayad) Bishay (April 16, 2016 -

Economy

The economy of Luxor, like that of many other Egyptian cities, is heavily dependent on tourism. Since 1988, Luxor is the only city that offers hot air balloon rides in Egypt, which is a common activity for tourists. Large numbers of people also work in agriculture, particularly sugarcane. There are also many industries, such as the pottery industry used in eating and many other uses.

The local economy was hit by the Luxor massacre in 1997, in which a total of 64 people (including 59 visiting tourists) were killed, at the time the worst terrorist attack in Egypt (before the Sharm el-Sheikh terrorist attacks).[28] The massacre reduced tourist numbers for several years.[29] Following the 2011 Arab Spring, tourism to Egypt dropped significantly, again affecting local tourist markets. Nineteen Asian and European tourists died when a hot air balloon crashed early on Tuesday, February 26, 2013 near Luxor following a mid-air gas explosion. It was one of the worst accidents involving tourists in Egypt. The casualties included French, British, Hungarian, Japanese nationals and nine tourists from Hong Kong.[30]

To make up for shortfalls of income, many cultivate their own food. Goat's cheese, pigeons, subsidized and home-baked bread and homegrown tomatoes are commonplace among the majority of its residents.

Tourism development

.jpg.webp)

A controversial tourism development plan aims to transform Luxor into the biggest vast open-air museum. The master plan envisions new roads, five-star hotels, glitzy shops, and an IMAX theatre. The main attraction is an 11 million dollar project to unearth and restore the 2.7 kilometres (1.7 miles) long Avenue of Sphinxes that once linked Luxor and Karnak temples. The ancient processional road was built by the pharaoh Amenhotep III and took its final form under Nectanebo I in 400 BCE. Over a thousand sphinx statues lined the road now being excavated which was covered by silt, homes, mosques and churches. Excavation started around 2004.[31][32]

On 18 April 2019, the Egyptian Government announced the discovery of a previously unopened coffin in Luxor, dated back to 18th dynasty of Upper and Lower Egypt.[33][34] According to the Minister of Antiquities Khaled al-Anani, it is the biggest rock-cut tomb to be unearthed in the ancient city of Thebes.[35] It is one of the largest, well-preserved tombs ever found near the ancient city of Luxor.[36] On 24 November 2018, this discovery was preceded by the finding of a well-preserved mummy of a woman inside a previously unopened coffin dating back more than 3,000 years.[37][38]

Infrastructure

Transport

Luxor is served by Luxor International Airport.

A bridge was opened in 1998, a few kilometres upstream of the main town of Luxor, allowing ready land access from the east bank to the west bank. Traditionally river crossings have been the domain of several ferry services. The so-called 'local ferry' (also known as the 'National Ferry') continues to operate from a landing opposite the Temple of Luxor.

Transport to sites on the west bank are serviced by taxi drivers who often approach ferry passengers. There are also local cars that reach some of the monuments for 2 L.E., although tourists rarely use them. Alternatively, motorboats line both banks of the Nile all day providing a quicker, but more expensive (50 L.E.), crossing to the other side.

The city of Luxor on the east bank has several bus routes used mainly by locals. Tourists often rely on horse carriages, called "calèches", for transport or tours around the city. Taxis are plentiful, and reasonably priced, and since the government has decreed that taxis older than 20 years will not be relicensed, there are many modern air-conditioned cabs. Recently, new roads have been built in the city to cope with the growth in traffic.

For domestic travel along the route of the Nile, a rail service operates several times a day. A morning train and sleeping train can be taken from the railway station situated around 400 metres (440 yd) from Luxor Temple. The line runs between several major destinations, including Cairo to the north and Aswan to the south.

Luxor University

Luxor University, founded in 2019, is a non-profit governmental university that provides programs and courses for students.[39]

Twin towns – sister cities

Luxor is twinned with:

Gallery

Station Street in Luxor

Station Street in Luxor.jpg.webp) Street market in Luxor

Street market in Luxor The New Corniche in Luxor

The New Corniche in Luxor Sunset on Nile River in Luxor, Feluccas

Sunset on Nile River in Luxor, Feluccas Luxor Temple as seen from River Nile

Luxor Temple as seen from River Nile Panoramic view of Luxor

Panoramic view of Luxor Luxor Temple

Luxor Temple Central corridor and four colossi by night

Central corridor and four colossi by night Ramesses II colossus inside Luxor Temple at night

Ramesses II colossus inside Luxor Temple at night Amenhotep's colonnade from the peristyle court

Amenhotep's colonnade from the peristyle court Hundreds of sphinxes once lined the road to nearby Karnak

Hundreds of sphinxes once lined the road to nearby Karnak The Abu Haggag Mosque inside the temple

The Abu Haggag Mosque inside the temple Luxor Temple and Abu Haggag Mosque

Luxor Temple and Abu Haggag Mosque Mosque in Mansheya Street

Mosque in Mansheya Street Hot Air Balloon In Luxor

Hot Air Balloon In Luxor New Tiba City: extension east of Luxor, started in 2000

New Tiba City: extension east of Luxor, started in 2000

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Data from Luxor.gov.eg". Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- 1 2 "Annual Bulletin of Births and Deaths Statistics 2020". CAPMAS. December 2021. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 1557.

- ↑ Macmillan & Co (1905). Guide to Egypt and the Sudan: Including a Description of the Route Through Uganda to Mombasa. Macmillan. p. 115.

- ↑ Verner, Miroslav (2013). Temple of the World: Sanctuaries, Cults, and Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, p. 232. ISBN 9789774165634. (Archived March 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Shahîd, Irfan (2002). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, p. 68. ISBN 9780884022848. (Archived March 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 3 "TM Places". www.trismegistos.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ↑ Peust, Carsten (2010). Die Toponyme vorarabischen Ursprungs im modernen Ägypte. Göttingen. p. 10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "nwt - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. September 25, 2019. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "History of Luxor (Thebes)". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Archaeologists find bust of Roman emperor in Egypt dig in Aswan". Arab News. April 22, 2018. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ↑ DPA, Daily Sabah with (April 22, 2018). "Archeologists find Roman emperor bust, ancient shrine in Egypt". Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ↑ "Shrine to Osiris and bust of Roman emperor found in Egypt". www.digitaljournal.com. April 22, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "13th century priest's tomb discovered in Egypt's Luxor". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Ancient Egyptian tomb unveiled". BBC News. November 24, 2018. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Ancient Egyptian tomb unveiled". BBC News. November 24, 2018. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Ancient tomb unveiled in Egypt". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ Zaugg, Julie; Moustafa, Nourhan (October 11, 2019). "Egyptian archeologists uncover ancient 'industrial area' filled with royal artifacts". CNN. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ↑ ""Egyptian archeologists uncover ancient 'industrial area' filled with royal artifacts" – CNN – infodecay". Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ↑ Alaa Elassar (October 20, 2019). "Egypt unveils discovery of 30 ancient coffins with mummies inside". CNN. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Egypt archaeologists find 20 ancient coffins near Luxor". BBC News. October 16, 2019. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ↑ Luxor, Reuters in (October 19, 2019). "Archaeologists discover 30 ancient coffins in Luxor". the Guardian. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ Beachum, Lateshia. "Archaeologists discover more than 20 sealed coffins just as the ancient Egyptians left them". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- 1 2 "Inside Egypt's 3,000-year-old 'lost golden city'". October 4, 2021. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Luxor, Egypt". Voodoo Skies. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Luxor Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Luxor Climate Normals 1961–1990". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Reference Normals (1961–1990). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Shock in Sharm Archived 2013-09-24 at the Wayback Machine 23 July, Serene Assir, Al-Ahram Weekly

- ↑ "Solidly ahead of oil, Suez Canal revenues, and remittances, tourism is Egypt's main hard currency earner at $6.5 billion per year." (in 2005) ... concerns over tourism's future Archived 2013-09-24 at the Wayback Machine accessed 27 September 2007

- ↑ (Times of India, Indore, MP, India edition Wed, February 27, 2013)

- ↑ McGrath, Cam (June 16, 2011). "Mideast: Sphinx Avenue Paved With Bitter Memories — Global Issues". Globalissues.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ↑ McGrath, Cam (June 16, 2011). "Mideast: Sphinx Avenue Paved With Bitter Memories — Global Issues". Globalissues.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Expansive New Kingdom tomb unveiled in Egypt's Luxor". reuters.com. April 18, 2019. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ Mustafa Marie (April 18, 2019). "Egypt announces tomb discovery at Luxor's Draa Abul Naga necropolis". Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Ancient Egyptian Mayor's Tomb Discovered in Luxor (with video)". luxortimes.com. April 18, 2019. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ "'Astonishing' 3,500-year-old Egyptian tombs discovered in Luxor". ctyvnews.ca. April 18, 2019. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Egyptian archaeologists unveil newly discovered Luxor tombs". telegraph.co.uk. November 24, 2018. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ Randa Ali (November 26, 2018). "13th century priest's tomb discovered in Egypt's Luxor". abcnews.go.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Luxor University Official Site". Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ↑ "Baltimore Sister Cities". baltimoresistercities.org. Baltimore Sister Cities, Inc. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Cidades Irmãs". internacional.df.gov.br (in Portuguese). Escritório de Assuntos Internacionais, Governo do Distrito Federal. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ↑ "Georgia's wine region twins with Egypt's Luxor". agenda.ge. March 11, 2015. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Побратимени градове". kazanlak.bg (in Bulgarian). Kazanlak. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Luxor". sz.gov.cn. Shenzhen. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Viterbo gemellata con Luxor". almaghrebiya.it (in Italian). Al Maghrebiya. August 9, 2020. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province: Overview". chinadaily.com.cn. China Daily. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

Further reading

- Bell, Lanny. “Luxor Temple and the Cult of the Royal ka.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 44 (1985): 251–294.

- Bongioanni, Alessandro. Luxor and the Valley of the Kings. Vercelli, Italy: White Star Publishers, 2004.

- Brand, Peter J. “Veils, Votives and Marginalia: The Use of Sacred Space at Karnak and Luxor.” In Sacred Space and Sacred Function in Ancient Thebes. Edited by Peter F. Dorman and Betsy N. Bryan, 51–83. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- El-Shahawy, Abeer, and Farid S. Atiya. Luxor Museum: The Glory of Ancient Thebes. Cairo, Egypt: Farid Atiya Press, 2005.

- Haag, Michael. Luxor Illustrated: With Aswan, Abu Simbel, and the Nile. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2009.

- Siliotti, Alberto. Luxor, Karnak, and the Theban Temples. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2002.

- Strudwick, Nigel, and Helen Strudwick. Thebes In Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Weeks, Kent R. The Illustrated Guide to Luxor: Tombs, Temples, and Museums. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

External links

| Library resources about Luxor |

- Theban Mapping Project: website devoted to the Valley of the Kings and other sites in the Theban Necropolis

- Luxor World Heritage Site in panographies - 360 degree interactive imaging

- GCatholic Copic epachy

- Kamil, Jill (November 2008). "The Development Plan for Luxor". Al-Ahram Weekly, Issue No. 921. Archived from the original on August 6, 2009.

- Luxor Temple picture gallery at Remains.se