Kom Ombo

كوم أمبو | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Tour boats at the Temple of Kom Ombo | |

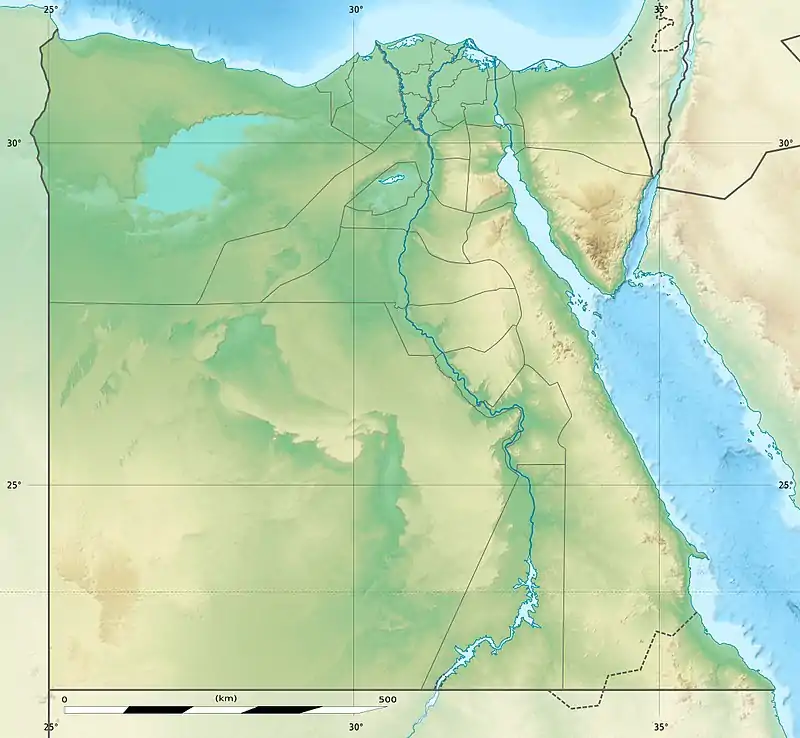

Kom Ombo Location in Egypt | |

| Coordinates: 24°28′N 32°57′E / 24.467°N 32.950°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aswan Governorate |

| Area | |

| • Total | 415 sq mi (1,076 km2) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

| • Total | 409,311 |

| • Density | 990/sq mi (380/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

Kom Ombo (Egyptian Arabic: كوم أمبو; Coptic: ⲙ̄ⲃⲱ əmbō or ⲛ̄ⲃⲱ ənbō;[2] Ancient Greek: Ὄμβοι Omboi [3][4][5] or Ὄμβος Ombos;[6] or Latin: Ambo[7] and Ombi is an agricultural town in Egypt famous for the Temple of Kom Ombo. It was originally an Egyptian city called Nubt, meaning City of Gold (not to be confused with the city north of Naqada that was also called Nubt/Ombos). Nubt is also known as Nubet or Nubyt (Nbyt).[8] It became a Greek settlement during the Greco-Roman Period. The town's location on the Nile, 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of Aswan (Syene), gave it some control over trade routes from Nubia to the Nile Valley, but its main rise to prominence came with the erection of the Temple of Kom Ombo in the 2nd century BC.

History

| nbt[9][10] in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BC) | ||||

In antiquity the city was in the Thebaid, the capital of the Nomos Ombites, on the east bank of the Nile; latitude 24° 6' north. Ombos was a garrison town under every dynasty of Egypt as well as the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Roman Egypt, and was celebrated for the magnificence of its temples and its hereditary feud with the people of Dendera.

Ombos was the first city below Aswan at which any remarkable remains of antiquity occur. The Nile, indeed, at this portion of its course, was ill-suited to a dense population in antiquity. It runs between steep and narrow banks of sandstone, and deposits but little of its fertilizing slime upon the dreary and barren shores. There are two temples at Ombos, constructed of the stone obtained from the neighboring quarries of Hagar Silsilah.

The more magnificent of two stands upon the top of a sandy hill, and appears to have been a species of Pantheon, since, according to extant inscriptions, it was dedicated to Haroeris and the other deities of the Ombite nome by the soldiers quartered there. The smaller temple to the northwest was sacred to the goddess Isis. Both, indeed, are of an imposing architecture, and still retain the brilliant colors with which their builders adorned them. However, they are from the Ptolemaic Kingdom, with the exception of a doorway of sandstone, built into a wall of brick. This was part of a temple built by Thutmose III in honor of the crocodile-headed god Sobek. The monarch is represented on tress, the doorjambs, holding the measuring reed and chisel, the emblems of construction, and in the act of dedicating the temple.

The Ptolemaic portions of the larger temple present an exception to an almost universal rule in Egyptian architecture. It has no propylon or dromos in front of it, and the portico has an uneven number of columns, in all fifteen, arranged in a triple row. Of these columns, thirteen are still erect. As there are two principal entrances, the temple would seem to be two united in one, strengthening the supposition that it was the Pantheon of the Ombite nome. On a cornice above the doorway of one of the adyta, there is a Greek inscription, recording the erection, or perhaps the restoration of the sekos by Ptolemy VI Philometor and his sister-wife Cleopatra II, 180-145 BCE. The hill on which the Ombite temples stand has been considerably excavated at its base by the river, which here strongly inclines to the Arabian bank.

The crocodile was held in especial honor by the people of Ombos; and in the adjacent catacombs are occasionally found mummies of the sacred animal. Juvenal, in his 15th satire, has given a lively description of a fight, of which he was an eye-witness, between the Ombitae and the inhabitants of Dendera, who were hunters of the crocodile. On this occasion the men of Ombos had the worst of it; and one of their number, having stumbled in his flight, was caught and eaten by the Denderites. The satirist, however, has represented Ombos as nearer to Dendera than it actually is, these towns, in fact, being nearly 100 miles (160 km) from each other. The Roman coins of the Ombite nome exhibit the crocodile and the effigy of the crocodile-headed god Sobek.

In Kom Ombo there is a rare engraved image of what is thought to be the first representation of medical instruments for performing surgery, including scalpels, curettes, forceps, dilator, scissors and medicine bottles dating from the days of Roman Egypt.

At this site there is another Nilometer used to measure the level of the river waters. On the opposite side of the Nile was a suburb of Ombos, called Contra-Ombos.

The city was the seat of a bishop during Late Antiquity. Two bishops of Omboi are known by name, Silbanos (before 402) and Verses (402).[11] Under the name Ombi, it is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees. Karol Wojtyła (the future Pope John Paul II) was titular bishop of Ombi from 1958 until 1963, when he was appointed Archbishop of Kraków.[12]

Geography

Climate

The Köppen climate classification classifies its climate as hot desert (BWh).

| Climate data for Kom Ombo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

26 (79) |

30 (86) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

41.2 (106.2) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.9 (105.6) |

38.6 (101.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

33.9 (93.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26 (79) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

28 (82) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24 (75) |

24.2 (75.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10 (50) |

17.3 (63.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[13] | |||||||||||||

Today

Today, irrigated sugarcane and cereal account for most of the agricultural industry.

Most of the 60,000 villagers are native Egyptians, although there is a large population of Nubians, including many Magyarabs[14] who were displaced from their land upon the creation of Lake Nasser.

In 2010, plans to construct a new $700m 100 MW (130,000 hp) solar power plant near the city were unveiled by the Egyptian government.[15]

Gallery

Cleopatra image at the Temple of Kom Ombo.

Cleopatra image at the Temple of Kom Ombo..JPG.webp) Medical instruments image at the Temple of Kom Ombo, showing scalpels, forceps, scissors, plus prescriptions and two goddesses sitting on birthing chairs.

Medical instruments image at the Temple of Kom Ombo, showing scalpels, forceps, scissors, plus prescriptions and two goddesses sitting on birthing chairs. A painting from the ceiling of the temple at Kom Ombo.

A painting from the ceiling of the temple at Kom Ombo.

Kom Ombo, main part of the temple

Kom Ombo, main part of the temple Giant Relief

Giant Relief

See also

References

- 1 2 "Kawm Umbū (Markaz, Egypt) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ↑ "Omboi (Kom Ombo)". Trismegistos.

- ↑ Ptol. iv. 5. § 73

- ↑ Steph. B. s. v.

- ↑ It. Anton. p. 165

- ↑ Juv. xv. 35

- ↑ Not. Imp. sect. 20

- ↑ "Trismegistos". www.trismegistos.org. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ↑ Wallis Budge, E. A. (1920). An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary: with an index of English words, king list and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, coptic and semitic alphabets, etc. Vol. 2. John Murray. p. 1005.

- ↑ Gauthier, Henri (1926). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques. Vol. 3. p. 83.

- ↑ Klaas A. Worp (1994), "A Checklist of Bishops in Byzantine Egypt (A.D. 325 – c. 750)" (PDF), Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 100: 283–318, at .

- ↑ "Ombi". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ "Climate: Kom Ombo - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Cata.org. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Lassányi, Gábor; Gergely Lantai-Csont (2014). Eltűnő Núbia: Válogatás Lantai-Csont Gergely szudáni fotóiból [Disappearing Nubia: Selection from Gergely Lantai-Csont's photos from Sudan]. Translated by Zsolt Magyar. Budapest: BTM. pp. 16–23. ISBN 978-615-5341-09-0.

- ↑ "The Guardian, July 12, 2010". Guardian. London. 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ↑ mondial, UNESCO Centre du patrimoine. "Pharaonic temples in Upper Egypt from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO Centre du patrimoine mondial (in French).

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Kom Ombo". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Kom Ombo". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.