Long dice[1] (sometimes oblong[2] or stick[2][3] dice) are dice, often roughly right prisms or (in the case of barrel dice) antiprisms, designed to land on any of several marked lateral faces, but neither end. Landing on end may be rendered very rare simply by their small size relative to the faces, by the instability implicit in the height of the dice, and by rolling the long dice along their axes rather than tossing. Many long dice provide further insurance against landing on end by giving the ends a rounded or peaked shape, rendering such an outcome physically impossible (at least on a flat solid surface).

Design advantages of long dice include being relatively easy to create fair dice with an odd number of faces, and (for four-faced dice) being easier to roll than tetrahedral d4 dice (as found in many role-playing games).

Four faces (square prisms)

Both cubic dice and four-faced long dice are found as early as the mid third millennium BCE at Indus Valley civilisation sites; these are marked variously with dot-and-ring figures, linear devices, and Indus Valley signs.[2] Dot-and-ring figures are used to this day on long dice in India, and predominate in the central European long dice shown above. In India, long dice (pasa) are used to play Chaupar (a relative of Pachisi); the faces may be marked with the values 1-3-4-6 or 1-2-5-6,[4] though older Indian long dice were marked 1-2-3-4.[5]

Similar dice were used by Germanic people before the Migration Period.[6] These include distinctive roughly ovoid Westerwanna-type dice (named for the site of their initial discovery in Lower Saxony); these are typically about 2 cm in length and marked with dot-and-ring figures of values 2-3-4-5.[7]

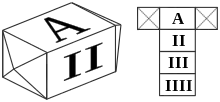

Long dice are used with the Scandinavian games Daldøs (typically marked A-II-III-IIII[8] or X-II-III-IIII[9]) and Sáhkku (with a variety of similar markings including X-II-III-[blank][10]); these dice may be so short as to exhibit nearly square faces, and therefore feature pyramidal ends.

More faces (n-gonal prisms)

A five-faced long die (pentagonal prism) is used in the Korean game of Dignitaries.[11]

Owzthat and similar forms of pencil cricket (a cricket simulation game) use two six-faced long dice (hexagonal prisms—like segments of a pencil).[12]

Though the traditional English Lang Larence ("Long Lawrence") was sometimes four-faced, it commonly appeared with eight faces (octagonal prism), even though they continued to display only four distinct values (each value being displayed on two faces).[13]

| Marking | Name | Result |

|---|---|---|

| XXXXXXXXXX | "Flush" | Take all counters from the pool |

| | | | | | | | "Put doan two" | Put 2 counters into the pool |

| \/\/\ | "Lave all" | Neither take nor put |

| | | | | "Sam up one" | Take 1 counter from the pool |

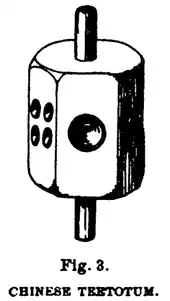

This gambling game played with the Lang Larence is the same as that usually played with teetotums. A teetotum is essentially a long die (though not necessarily physically long) with a spindle through its axis, allowing it to be spun and preventing it landing on end. Though many teetotums (for example, the dreidel) are four-faced, they may have any practical number of faces.

Four-faced dreidel

Four-faced dreidel Six-faced Chinese teetotum

Six-faced Chinese teetotum Twelve-faced teetotum

Twelve-faced teetotum

Barrel dice

Barrel dice are a more recent design, used most often by players of role playing games and wargames. They appear roughly cylindrical, and are generally modified antiprisms with between four and twenty flattened triangular facets, each numbered. Each triangular face alternates in alignment by 180 degrees. The two ends are formed by half as many triangular facets as there are numbered faces, arranged as a pyramid so that it is impossible for the die to stop on one of its ends.

References

- ↑ Culin 1898, pp 820, 825; Murray 1951, p 134; Bell 1960, p 10; Parlett 1999, p 26; Heijdt 2002, p 20.

- 1 2 3 Finkel 2004, p 39.

- ↑ Culin 1898, p 827.

- ↑ Parlett 1999, p 46.

- ↑ Parlett 1999, p 26.

- ↑ Heijdt 2002, p 91.

- ↑ Heijdt 2002, pp 92-93.

- ↑ Østergaard & Gaston 2001, p 15.

- ↑ Michaelson 2001, p 21. Note that in both Daldøsa (the Norwegian variant of Daldøs) and in Sáhkku, the "X" is not a roman numeral, but "marks the spot" of a special value: usually just "1", but with an additional privilege.

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p 50.

- ↑ Parlett 1999, p 26.

- ↑ "Owzthat". Dice Collector. Sports Dice: Cricket. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ Parlett 1999, p 27.

- ↑ Gomme 1894, pp 326-27.

Bibliography

- Bell, R. C. (1960), Board and Table Games [1] (rev. 1969 and rpt. with vol 2 as Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations Mineola, NY: Dover, 1979 ed.), London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-486-23855-5

- Borvo, Alan (2001), "Sáhkku, The "Devil's Game"" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 33–52, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Culin, Stewart (1898), Chess and Playing-Cards (rpt. New York: Arno Press, 1976 ed.), Washington DC: US National Museum, ISBN 0-405-07916-8

- Finkel, Irving (2004), "Dice in India and Beyond", in Mackenzie, Colin; Finkel, Irving (eds.), Asian Games: The Art of Contest, Asia Society, pp. 38–45, ISBN 0-87848-099-4

- Gomme, Alice (1894), The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland, vol. 1, London: David Nutt

- van der Heijdt, Leo (2002), Face to Face with Dice: 5000 Years of Dice and Dicing, Groningen, NL: Gopher Publishers, ISBN 90-76953-88-0

- Michaelsen, Peter (2001), "Daldøs, an almost forgotten dice board game" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 19–31, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Murray, H. J. R. (1951), A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess (rpt. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002 ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-827401-7

- Østergaard, Eric; Gaston, Anne (2001), "Daldøs — the rules" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 15–17, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Parlett, David (1999), The Oxford History of Board Games, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-212998-8