In astronomy, long-slit spectroscopy involves observing a celestial object using a spectrograph in which the entrance aperture is an elongated, narrow slit. Light entering the slit is then refracted using a prism, diffraction grating, or grism. The dispersed light is typically recorded on a charge-coupled device detector.[1]

Velocity profiles

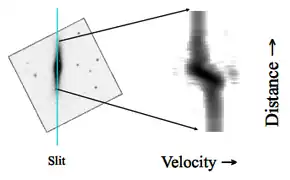

This technique can be used to observe the rotation curve of a galaxy, as those stars moving towards the observer are blue-shifted, while stars moving away are red-shifted.[2]

Long-slit spectroscopy can also be used to observe the expansion of optically-thin nebulae. When the spectrographic slit extends over the diameter of a nebula, the lines of the velocity profile meet at the edges. In the middle of the nebula, the line splits in two, since one component is redshifted and one is blueshifted. The blueshifted component will appear brighter as it is on the "near side" of the nebula, and is as such subject to a smaller degree of attenuation as the light coming from the far side of the nebula. The tapered edges of the velocity profile stem from the fact that the material at the edge of the nebula is moving perpendicular to the line of sight and so its line of sight velocity will be zero relative to the rest of the nebula.[3]

Several effects can contribute to the transverse broadening of the velocity profile. Individual stars themselves rotate as they orbit, so the side approaching will be blueshifted and the side moving away will be redshifted. Stars also have random (as well as orbital) motion around the galaxy, meaning any individual star may depart significantly from the rest relative to its neighbours in the rotation curve. In spiral galaxies this random motion is small compared to the low-eccentricity orbital motion, but this is not true for an elliptical galaxy. Molecular-scale Doppler broadening will also contribute.

Advantages

Long-slit spectroscopy can ameliorate problems with contrast when observing structures near a very luminous source. The structure in question can be observed through a slit, thus occulting the luminous source and allowing a greater signal-to-noise ratio. An example of this application would be the observation of the kinematics of Herbig-Haro objects around their parent star.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Sloan, Gregory C. (December 20, 2007). "Long-slit spectroscopy" (Website). Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ↑ Vogt, Nicole. "Example: Galaxy Rotation Curve" (Website). Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ↑ Böhm-Vitense, Erika (January 31, 1992). Introduction to Stellar Astrophysics. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-521-34871-3.

- ↑ "Observing the Bipolar Jet Phase". Jetset. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.