Lomé | |

|---|---|

City | |

From top, left to right: Palace of the Governors, headquarters of the West African Development Bank, Monument Colombe de la Paix, Lomé Beach, and the Grande Marché in front of the Sacred Heart Cathedral. | |

Coat of arms | |

Lomé Location in Togo | |

| Coordinates: 6°7′55″N 1°13′22″E / 6.13194°N 1.22278°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Maritime Region |

| Prefecture | Golfe |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Aouissi Lodé |

| Area | |

| • City | 99.14 km2 (38.28 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 280 km2 (110 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2023 census) | |

| • City | 1,500,000 |

| • Density | 15,000/km2 (40,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,000,000 |

| • Metro density | 7,150/km2 (18,500/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC |

| HDI (2019) | 0.579[1] medium · 1st |

Lomé (UK: /ˈloʊmeɪ/ LOH-may, US: /loʊˈmeɪ/ loh-MAY) is the capital and largest city of Togo. It has an urban population of 837,437[2] while there were 1,477,660 permanent residents in its metropolitan area as of the 2010 census.[2] Located on the Gulf of Guinea at the southwest corner of the country, with its entire western border along the easternmost point of Ghana's Volta Region, Lomé is the country's administrative and industrial center, which includes an oil refinery. It is also the country's chief port, from where it exports coffee, cocoa, copra, and oil palm kernels.

Its city limits extends to the border with Ghana, located a few hundred meters west of the city center, to the Ghanaian city of Aflao and the South Ketu district where the city is situated, had 160,756 inhabitants in 2010. The cross-border agglomeration of which Lomé is the centre, has about 2 million inhabitants as of 2020.

Etymology

The name 'Lomé' comes from Alo(ti)mé or (shorter) Alomé, which in the Ewe language, literally, means "in the alo trees", or "within the alo trees", to designate simply the forest of alo.

For the record, Alo-ti or alo is a tree whose wood is being used by native people and is today produced also in factories, to make small logs very popular that are used as traditional toothpicks, especially in Lomé and the south of the country.

History

.jpg.webp)

The city was founded by the Ewes and thereafter in the 19th century by German, British and African traders,[3] becoming the capital of Togoland in 1897.[4] At the end of the nineteenth century, British customs duties on imported products (especially on alcohol and tobacco) weighed very heavily. The traders (mainly maritime Ewe or Anlo from the area between Aflao and Keta in the east of the British colony of Gold Coast) then looking for an alternative, a place to unload goods while being out of reach of British customs officers, naturally targeted the coastal site of Lomé, nearby. This commercial dynamic of customs circumvention and tax evasion then favored the expansion of Lomé around 1880. The calm and sparsely inhabited Loméen coastline began to be populated rapidly. The Ewes were soon joined by European, British and especially German companies, as well as itinerant merchants from the interior, such as the Hausa caravans from the cola roads. Many people were attracted by the new economic hub that represented Lomé. The rapid growth of the city was reinforced and Lomé quickly had the reputation of a place where good business was done.

Colonial period

It was the threats of the British present in the neighboring Gold Coast (now Ghana) to put an end to the unbearable competition that Lomé provoked on their colony, which then provoked the call for the protection of Germany, and thus the creation of Togoland occurred as an entity of international law within the German colonial empire on 5 July 1884, by the Treaty of Togoville signed by Gustav Nachtigal and King Mlapa III.

Lomé continued freely to prosper as a centre of import, thus becoming the main gateway to the North, whose major axis of penetration was then the Volta Valley; it was to access it that the construction of the first real road in the country, Lomé-Kpalimé, was undertaken from 1892. It was this major economic role that led the German administration to transfer the capital of the territory to a city that already had more than 2,000 inhabitants.[5]

Lomé benefited from 1904 from a port that made it the only maritime contact point of Togo, ruining without recourse its rival of Aného, until then much more important. From this development, a network of railways could be deployed: to Aného in 1905, to Kpalimé in 1907 and to Atakpamé in 1909. All the "useful Togo" was now organized in a funnel around Lomé, whose preponderance on the Togolese urban network was definitively established and growth assured; The city reached a population of 8,000 in 1914. But, if the infrastructure set up by the Germans, which were a post office in 1890, the telephone in 1894, the cathedral in 1904, a bank in 1906 and the intercontinental telegraph in 1913 could benefit everyone, a system of discriminatory patents and licenses gradually ousted African traders from the most lucrative activities, that is to say, the trade or the import-export activities.

Apart from the rich Octaviano Olympio, with his large Cocoterais, the first in the city, his herds, his brickyard and his construction company, most Togolese merchants had to put themselves at the service of foreign firms as managers of their agencies in other cities, or enjoying more autonomy as buyers of agricultural export products in the interior. The smallest had been hired in large numbers as clerks in the main factories (headquarters of the offices of a trading company abroad). Firms in other African territories looked with envy at Togo, which had an abundant skilled workforce, while elsewhere, it was necessary to entrust all positions to expatriates, much more expensive for the employer.

The First World War completely spared the city, but in 1916, it led to the eviction of German companies, gradually replaced by British and French firms. Many Togolese traders returned to Lomé. Their flourishing businesses, their vast coconut groves, their land patrimony made them a bourgeoisie with which the new French colonial authorities had to reckon, this was the meaning of the council of notables created in 1922 (elective from 1925), which gave Lomé a remarkably early political life in French-speaking Africa. It is also quite exceptional that an African capital has been so marked by its indigenous bourgeoisie (originally from the France), both in the production practices of urban space, so original in Lomé, and in the singularities of its popular architecture.

The French renewed the infrastructure left by the Germans; the repair of railways, multiplication of roads, construction of a new quay, etc. They added electrification in 1926 and drinking water supply in 1940), which their predecessors had not been able to achieve. However, they took years to fill the void left in the schools by the German verbist missionaries when they left. The level of students enrolled in 1945, at the death of Jean-Marie Cassou, reached that of 1914.

In the 1920s, a policy of systematic low taxation allowed for a long prosperity. In January 1923, a Révolte des femmes de Lomé took place against the arrest of two Duawo leaders and allowed their release.[6]

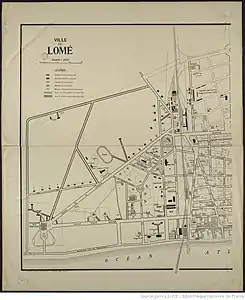

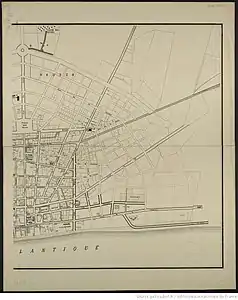

- Map of the city of Lomé in 1931

Left part

Left part Right part

Right part

Lomé reached 15,000 inhabitants around 1930. But the global economic crisis of the early 1930s led to a brutal recession. Many commercial firms closed, or had to consolidate. Investments stopped, like the Northern Railway, definitively stopped in Blitta in 1934. A plan for a sharp tax increase, while the people's resources were falling, provoked the riots of January 1933, which were undoubtedly a major political break in the history of Togo. It was only after the Second World War, after a decade of economic stagnation, that the boom resumed in Lomé where everything was bubbling with vitality.

Independence

The population of the city increased rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century. It had only a population of 30,000 in 1950, which increased to 80,000 in 1960, the year when Togo became independent. A decade later, it stood at 200,000 people, in 1970. Within two decades, the population of Lomé increased by seven-fold. The city, as throughout the country, the very high prices of export products operate the markets, the significant investments of the colonial administration (the "FIDES" plan created a large number of roads, bridges, schools, hospitals) ensured full employment. The constructions were rapidly expanding at the expense of the old coconut groves, the hope animated each of an imminent take-off.

From the mid-1970s, investments became more and more gigantic, but not always in well-targeted areas, Togo, a small open country and hub of trade between its powerful neighbors, did not have the protected market that would have been needed for the large industries that were built for it, nor the stable tourism potential for the luxurious hotels that were coming up.[7] At the same time, the railways were allowed to deteriorate, even though they had an important role, especially for serving the outlying districts of the city.

But, the economic activity of an African city is not just an accumulation of large companies, banks and factories. There is also the very vast field of the popular economy, these innumerable activities of production, exchange, service, repair, which are in fact the livelihood of the majority of the population, and the only way for it to access services commensurate with its modest resources. Difficult to grasp in the statistical tools of economists, the informal sector is increasingly affecting the real economic life of African city dwellers. In addition, the development of market gardening around the city, stimulated by growing unemployment, arose rural exodus and demand for vegetables. Market gardening, first extended to the north, is mainly on the beach (as the sand is too less salty), planting protective hedges. The various studies of the city's land market indicate that the neighborhoods are relatively heterogeneous, mixing opulent villas and modest housing, without social and spatial division of the city. This is explained by the fact that Lomeans are very attached to their plot of land and what they call their "home" (their home). This, therefore, led to a land freeze. However, if the city is not a socially divided city, the fact remains that Lomé is experiencing more and more problems related to the collection of household waste, the fight against urban insalubrity has become one of the priorities of the city and its inhabitants.

Climate

Owing to its location in the Dahomey Gap, Lomé has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) despite its latitude close to the equator. The capital of Togo is relatively dry with an annual average rainfall of 800 to 900 millimetres (31 to 35 in) and on average 59 rainy days per year. Despite this, the city experiences heavy fog most of the year from the northern extension of the Benguela Current and receives a total of 2,330 bright sunshine hours annually. Comparably dry inland West African cities like Bamako or Kano expect between 2,900 and 3,000 hours of sunshine annually.

The annual mean temperature is about 26.9 °C or 80.4 °F but heat is constant as monthly mean temperatures range from 24.9 °C or 76.8 °F in July, the least hot month of the year to 29.6 °C or 85.3 °F in February and in April, the hottest months of the year.

| Climate data for Lomé (Lomé Airport) 1991-2020 normals, extremes 1892-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.7 (96.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.5 (95.9) |

33.8 (92.8) |

38.1 (100.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.3 (0.52) |

16.4 (0.65) |

67.3 (2.65) |

97.3 (3.83) |

148.8 (5.86) |

180.5 (7.11) |

74.4 (2.93) |

30.1 (1.19) |

72.3 (2.85) |

101.9 (4.01) |

20.4 (0.80) |

7.6 (0.30) |

830.3 (32.69) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1.2 | 1.9 | 4.5 | 7.5 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 80.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 87 | 86 | 86 | 85 | 84 | 82 | 84 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 222.4 | 214.8 | 228.0 | 218.0 | 217.8 | 141.3 | 135.4 | 147.5 | 168.4 | 218.0 | 240.6 | 227.2 | 2,379.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (humidity and sunshine 1961–1990)[8][9] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[10] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

A 2019 paper published in PLOS One estimated that under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, a "moderate" scenario of climate change where global warming reaches ~2.5–3 °C (4.5–5.4 °F) by 2100, the climate of Lomé in the year 2050 would most closely resemble the current climate of Managua in Nicaragua. The annual temperature would increase by 1 °C (1.8 °F), the temperature of the warmest month by 1.6 °C (2.9 °F), and of the coldest month by 2.1 °C (3.8 °F).[11][12] According to Climate Action Tracker, the current warming trajectory appears consistent with 2.7 °C (4.9 °F), which closely matches RCP 4.5.[13]

Moreover, according to the 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Lomé is one of 12 major African cities (Abidjan, Alexandria, Algiers, Cape Town, Casablanca, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Durban, Lagos, Lomé, Luanda and Maputo) which would be the most severely affected by the future sea level rise. It estimates that they would collectively sustain cumulative damages of USD 65 billion under RCP 4.5 and USD 86.5 billion for the high-emission scenario RCP 8.5 by the year 2050. Additionally, RCP 8.5 combined with the hypothetical impact from marine ice sheet instability at high levels of warming would involve up to 137.5 billion USD in damages, while the additional accounting for the "low-probability, high-damage events" may increase aggregate risks to USD 187 billion for the "moderate" RCP4.5, USD 206 billion for RCP8.5 and USD 397 billion under the high-end ice sheet instability scenario.[14] Since sea level rise would continue for about 10,000 years under every scenario of climate change, future costs of sea level rise would only increase, especially without adaptation measures.[15]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) |

Geography

At its creation, the commune of Lomé was wedged between the lagoon to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, the village of Bè to the east and the border of Aflao to the west.

Today, it has experienced a vertiginous extension, and is bounded by the Togolese Insurance Group (GTA) to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, the oil refinery to the east, and the Togo-Ghana border to the west. The agglomeration spreads over an area of 333 sq.km. including 30 sq.km. in the lagoon area.

The services of the municipality of Lomé go far beyond the limits of the gulf and the municipality to the north and east of the city.

Distance between Lomé and the rest of the country's cities

Lomé/Tsévié : 35 km

Lomé/Aného : 45 km

Lomé/Tabligbo : 90 km

Lomé/Notsé : 100 km

Lomé/Kpalimé : 121 km

Lomé/Atakpamé : 167 km

Lomé/Blitta : 273 km

Lomé/Sokodé : 355 km

Lomé/Bafilo : 404 km

Lomé/Bassar : 412 km

Lomé/Kara : 428 km

Lomé/Kandé 503 km

Lomé/Mango : 592 km

Lomé/Dapaong : 662 km

Districts and cities of Lomé

The city of Lomé is subdivided into 5 arrondissements grouping 69 administrative districts Catégorie:Quartier de Lomé:

1st arrondissement: To the south along the ocean, it is the historic city, which is surrounded by the circular boulevard (Boulevard du 13 juillet) and includes the 11 districts of:

Abobokomé, Adawlato, Adoboukomé, Agbadahonou, Aguia Komé, Béniglato, Fréau Jardin, Kokétimé, Quartier Administratif, Sanguéra and Wétrivi Kondji.

2nd arrondissement: From the north to northeast and bordering the maritime region, it includes the 18 districts of:

Adakpamé, Akodesséwa-Kponou, Akodesséwa-Kpota, Anfamé, Atiégou, Avénou (Batome), Bè-Kpota, Hédzranawoé, Kagnikopé, Kélégougan, Lomé 2, N'tifafakomé, Résidence du Bénin, Saint-Joseph, Tokoin-N'kafu (Noukafou), Tokoin-Aéroport, Tokoin-Forever, Tokoin-Tamé and Tokoin-Wuiti.

3rd arrondissement: To the east, along the sea, it includes the 17 districts of:

Ablogamé, Akodésséwa (and the fetish market), Amoutivé, Anthonio Nétimé, Bassadji, Bè, Bè-Ahligo, Bè-Apéhémé, Bè-Hédjé, Doulassamé, Gbényédi, Kotokou Kondji, Kpéhénou, Lom Nava, Souza Nétimé, Wété and Port Area.

4th arrondissement: In the southwest, along the sea and bordering Ghana, it includes the 4 districts of:

Hanukope, Kodjoviakopé, Nyékonakpoé and Octaviano Nétimé.

5th arrondissement: To the northwest and bordering Ghana to the east and the maritime region to the north, it includes the 19 districts of:

Abové, Aflao Gakli, Agbalépédogan, Akossombo, Bè-Klikamé, Cassablanca, Dogbéavou, Doumasséssé, Gbonvié, Soviépé, Tokoin-Elavagnon, Tokoin-Gbadago, Tokoin-Hopital, Tokoin-Lycée, Tokoin-Ouest, Tokoin-Solidarité and Totsi (includes Totsigan and Totsivi).

The former districts (now subdivided) are Dékon, Tokoin, Xédranawoe, Adjangbakomé and Adidogomé. The other cities composing the agglomeration of Lomé are Adewi, Agbalépédogan, Agoè, Attikoumè, Avédji, Baguida, Djidjolé, Kélékougan and Kpogan.

International agreements

Lomé Convention

The Lomé Convention is a trade and aid agreement between the European Union (EU) and 71 African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries. It was first signed on 28 February 1975, in Lomé.[7]

Lomé Peace Accord

The Lomé Peace Accord between the warring parties in the civil war in Sierra Leone was signed in Lomé. With the assistance of the international community, Sierra Leone President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah and Revolutionary United Front leader Foday Sankoh signed the Peace Accord on 7 July 1999. However, the agreement did not last and the war continued for two more years.

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Located 200 km from Accra and 150 km from Cotonou, Lomé has an important port, including a free zone opened in 1968. Phosphates, coffee, cocoa, cotton and palm oil are exported and much of the transit is on behalf of Ghana, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. The port is also home to an oil refinery and, since 1989, a shipyard.[16] The concession of two container terminals to the Bolloré group gave rise to police custody[17] and indictment of Vincent Bolloré in France in April 2018.[18]

The city produces building materials, including cement from the German group, HeidelbergCement.

However, the political instability that began in the 1990s and continues today has severely affected the country's tourism sector. In 2003, the country received 57,539 visitors, an increase of 1 per cent over 2002. 22% of tourists came from France, 10% from Burkina Faso and 9% from Benin.

Demographics

|

|

Culture

The Togo National Museum is in the Palais de Congrès. The museum contains collections such as jewellery, musical instruments, dolls, pottery, weapons and many other materials showing arts and traditions.

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The city center dates from the early twentieth century. There are some remains of colonial architecture, such as the Palace of the Governors or the Sacred Heart Cathedral, in German neo-Gothic style.

There are also many modern buildings such as the headquarters of the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), the West African Development Bank (BOAD), the Togolese Bank for Trade and Industry (BTCI), the Economic Community of West African States (ECoWAS) or hotel buildings such as the Hotel de la Paix, the Mercure Sarakawa Hotel, the Palm Beach Hotel or the famous Hotel du 2 Février, a modernist building mixing concrete and glass panels, culminating at 102 meters with 36 floors, and is the tallest building in Togo.

Not far away is the Grand Market, with a three-storey hall. There are red peppers, limes, dried fish, combs, travel bags, traditional medicinal remedies. On the first floor is the kingdom of the famous "Nana Benz", sellers of multiple loincloths made locally, in Europe or India. To the west of the city is a residential area which, facing the sea, unfolds long arteries, punctuated by official buildings such as the Palace of Justice and various embassies and consulates.

Further north, next to the Independence Monument, is the headquarters of the Rally of the Togolese People (RPT) and an important convention center.

More eccentric, compared to the center of the city, we find in Akodesséwa, a much more specialized market than the large market and for good reason, it is the fetish market. Fetishes, gongons, gray-gray are found here. The port of Lomé serves most of the landlocked countries of the Sahel, especially since the political problems experienced by Côte d'Ivoire and which deprives Abidjan of an economic outlet for countries such as Mali or Burkina Faso. Lomé is therefore taking advantage of the difficult political situation in Côte d'Ivoire.

Places of worship

The Savior Baptist Church in Lomé (Togo Baptist Convention)

The Savior Baptist Church in Lomé (Togo Baptist Convention)

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Christian churches and temples : Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lomé (Catholic Church), Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Togo (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Togo Baptist Convention (Baptist World Alliance), Living Faith Church Worldwide, Redeemed Christian Church of God, Assemblies of God.[19] There are also Muslim mosques.

Education

.jpg.webp)

The University of Lomé (previously called University of Benin), located in Lomé Tokoin, was founded in 1970.

Schools located in the city include American International School of Lomé, British School of Lomé, Ecole Internationale Arc-en-Ciel and Lycée Français de Lomé.

Transport

Road

For urban transport, there are a few taxis, but it is the motorcycle taxis (zémidjans) which are most used.

Rail

The city, which had no rail service since 1997, has seen since 2014, the return of trains, with a new station: those of Blueline Togo, constructed by the French international firm, Bolloré.[20] The inaugural train on 26 April 2014 ran on the short distance Lomé to Cacavéli.[21] The under-construction of the Lomé-Cotonou link, as part of a rail loop project from Lomé, Cotonou, Niamey, Ouagadougou and to Abidjan, is expected to be completed by 2024.[22]

Air

The city is served by Lomé-Tokoin International Airport, located 5 km (3.1 mi) northeast from the city centre. ASKY Airlines, a subsidiary of Ethiopian Airlines, and itself, operates at the airport.

Water

The city has the Port of Lomé, which is the only commercial port of Togo that carries out trade and export-import activities in the country. It also has a cruise terminal where passengers are also served.

Taxis

Taxis Port of Lomé

Port of Lomé

Twin towns – sister cities

Lomé is twinned with:

Notable people

- Emmanuel Adebayor, retired footballer for Togo.

- Kangni Alem, writer

- Gnimdéwa Atakpama, journalist and writer

- Yaovi Aziabou, Togolese professional footballer

- Nicole Coste, Air France flight attendant, mother of Alexandre Coste (the son of Albert II, Prince of Monaco)

- Christiane Akoua Ekué, writer

- Sika Foyer, visual artist

- Emmanuel Kavi, artist

- Senam Langueh, Togolese former international footballer

- King Mensah, popular Afropop musician

- Amadou Morou, Togolese- Polish footballer

- Davide-Christelle Sanvee, Swiss performance artist of Togolese origin

- Marie Madoé Sivomey, first female mayor in Togo, served as mayor of Lomé from 1967 to 1974

References

- ↑ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- 1 2 Résultats définitifs du RGPH4 au Togo Archived 21 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑

- Philippe Gervais-Lambony (2011), Simon Bekker and Goran Therborn (ed.), "Lomé", Capital Cities in Africa: Power and Powerlessness, Dakar: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, ISBN 978-2-8697-8495-6, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 5 May 2016

- ↑ Britannica, Lomé, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 30 June 2019

- ↑ Britannica, Lomé, britannica.com, USA, accessed 28 July 2019

- ↑ Aduayon, Messan Adimado (1984). "Un prélude au nationalisme togolais : la révolte de Lomé, 24-25 janvier 1933". Cahiers d'Études africaines. 24 (93): 39–50. doi:10.3406/cea.1984.2226. Retrieved 31 December 2019..

- 1 2 Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 162

- ↑ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Lome". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ↑ "Lomé Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ↑ "Station Lome" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ↑ Bastin, Jean-Francois; Clark, Emily; Elliott, Thomas; Hart, Simon; van den Hoogen, Johan; Hordijk, Iris; Ma, Haozhi; Majumder, Sabiha; Manoli, Gabriele; Maschler, Julia; Mo, Lidong; Routh, Devin; Yu, Kailiang; Zohner, Constantin M.; Thomas W., Crowther (10 July 2019). "Understanding climate change from a global analysis of city analogues". PLOS ONE. 14 (7). S2 Table. Summary statistics of the global analysis of city analogues. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217592. PMC 6619606. PMID 31291249.

- ↑ "Cities of the future: visualizing climate change to inspire action". Current vs. future cities. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ↑ "The CAT Thermometer". Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ↑ Trisos, C.H., I.O. Adelekan, E. Totin, A. Ayanlade, J. Efitre, A. Gemeda, K. Kalaba, C. Lennard, C. Masao, Y. Mgaya, G. Ngaruiya, D. Olago, N.P. Simpson, and S. Zakieldeen 2022: Chapter 9: Africa. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke,V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2043–2121

- ↑ Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). IPCC. August 2021. p. TS14. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Edmond D'Almeida (25 December 2016). "Reportage : le Chantier naval de Lomé contre vents et marées". Jeune Afrique. Retrieved 26 December 2016..

- ↑ "Concessions portuaires à Lomé et Conakry : Bolloré en garde à vue". www.lemarin.fr. Retrieved 29 April 2018..

- ↑ "Vincent Bolloré mis en examen pour "corruption" dans l'affaire des ports africains". La Tribune. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018..

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘'Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices'’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 2875-2877

- ↑ "Vincent Bolloré : 'L'aventure commence maintenant'". www.republicoftogo.com. 26 April 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ Lancement du train Blueline Togo, reportage d'un journal télévisé local on YouTube.

- ↑ La bataille du rail africain

- ↑ "Städtepartnerschaften". duisburg.de (in German). Duisburg. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ "Lome". sz.gov.cn. Shenzhen. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ "International Sister Cities". tcc.gov.tw. Taipei City Council. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

.jpg.webp)