The life of Christ as a narrative cycle in Christian art comprises a number of different subjects showing events from the life of Jesus on Earth. They are distinguished from the many other subjects in art showing the eternal life of Christ, such as Christ in Majesty, and also many types of portrait or devotional subjects without a narrative element.

They are often grouped in series or cycles of works in a variety of media, from book illustrations to large cycles of wall paintings, and most of the subjects forming the narrative cycles have also been the subjects of individual works, though with greatly varying frequency. By around 1000, the choice of scenes for the remainder of the Middle Ages became largely settled in the Western and Eastern churches, and was mainly based on the major feasts celebrated in the church calendars.

The most common subjects were grouped around the birth and childhood of Jesus, and the Passion of Christ, leading to his Crucifixion and Resurrection. Many cycles covered only one of these groups, and others combined the Life of the Virgin with that of Jesus. Subjects showing the life of Jesus during his active life as a teacher, before the days of the Passion, were relatively few in medieval art, for a number of reasons.[1] From the Renaissance, and in Protestant art, the number of subjects increased considerably, but cycles in painting became rarer, though they remained common in prints and especially book illustrations.

Most common scenes

The main scenes found in art during the Middle Ages are:[2]

Birth and childhood sequence

These scenes also could form part of cycles of the Life of the Virgin:

- Annunciation to Mary, showing the conception of Jesus

- Nativity of Jesus in art

- Adoration of the Magi (Three Kings)

- Circumcision of Christ

- Presentation of Jesus

- Flight to Egypt, or the Massacre of the Innocents. Later sometimes the Rest on the Flight into Egypt.

- Finding in the Temple, the last episode of Jesus's childhood in the Canonical Gospels.

Mission period

.jpg.webp)

- Baptism of Jesus

- Miraculous catch of fish, more often found in Lives of apostles.

- Temptation of Christ, often divided into its three parts.

- Wedding at Cana, the first miracle recorded in the Gospels, and the only one at which Mary was present.

- The Samaritan woman at the well is occasionally depicted

- Transfiguration of Jesus, much more common in the Eastern than Western church

- Raising of Lazarus

- Jesus at the home of Martha and Mary, sometimes seen from the Counter-Reformation onwards.

Passion of Christ

- Christ taking leave of his Mother, a late medieval development, not based on any Gospel episode.

- Palm Sunday, Christ's entry into Jerusalem

- Jesus and the money changers, much more popular as a single subject from the Renaissance on

- Last Supper, and Washing of feet

- Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane

- Betrayal of Christ and Arrest of Jesus

- Denial of Peter – if included, usually the only Passion scene not to include Christ

- Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus

- Christ before Pilate

- Flagellation of Christ

- The Crowning with Thorns

- Mocking of Jesus

- Pensive Christ

- Ecce homo

- Christ carrying the Cross

- Veil of Veronica (Holy Face)

- Crucifixion in the arts, including:

- Descent from the Cross (Deposition of Christ)

- Lamentation of Christ and Pietà

- Epitaphios, or "Anointing of Christ"

- Entombment of Christ

- Harrowing of Hell, not in the Gospels

- Man of Sorrows

Resurrection to Ascension

- Resurrection of Jesus, which was not represented directly in the 1st millennium. Instead the Three Marys or Myrrhbearers finding an empty tomb was shown, or the next three scenes.

- Noli me tangere

- Meeting or Supper at Emmaus

- Doubting Thomas

- Ascension of Jesus in Christian art

Byzantine set of 12 scenes

In Byzantine art a fixed group of twelve scenes were often depicted as a set. These are sometimes described as the "Twelve Great Feasts", although three of them are different from the twelve modern Great feasts in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Neither group includes Easter/the Resurrection, which had a unique higher status. The group in art are: Annunciation, Nativity, Presentation, Baptism, Raising of Lazarus, Transfiguration, Entry into Jerusalem, Crucifixion of Jesus, Harrowing of Hell, Ascension, Pentecost, Dormition of the Theotokos (Death of the Virgin).[3]

Choice of scenes

_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg.webp)

After the Early Christian period, the selection of scenes to illustrate was led by the occasions celebrated as Feasts of the Church, and those mentioned in the Nicene Creed, both of which were given prominence by the devotional writers on whose works many cycles appear to be based. Of these, the Vita Christi ("Life of Christ") by Ludolph of Saxony and the Meditations on the Life of Christ were two of the most popular from the 14th century onwards. Another influence, especially in smaller churches, was liturgical drama, and no doubt also those scenes which lent themselves to a readily identifiable image tended to be preferred. Devotional practices such as the Stations of the Cross also influenced selection.

The miracles of Christ did not score well on any of these counts.[4] In Byzantine art written names or titles were commonly included in the background of scenes in art; this was much less often done in the Early Medieval West, probably not least because few laymen would have been able to read them and understand the Latin. The difficulties this could cause are shown in the 12 small narrative scenes from the Gospel of Luke in the 6th-century St. Augustine Gospels; about a century after the book was created captions were added to these images by a monk, which may already misidentify one scene.[5] It was around this time that miracle scenes, which had often been prominent in Early Christian art, became much more rare in the art of the Western Church.

However, some miracles commonly used as paradigms for Christian doctrines continued to be represented, especially the Wedding at Cana and Raising of Lazarus, which were both easy to recognise as images, with Lazarus normally shown tightly wrapped in a white shroud, but standing up. Paintings in hospitals were more likely to show scenes of the miraculous cures. An exception is St Mark's Basilica in Venice where a 12th-century cycle of mosaics originally had 29 scenes of the miracles (now 27), probably derived from a Greek gospel book.[6]

The scenes originating in the apocryphal Gospels that remain a feature of the depiction of Life of the Virgin have fewer equivalents in the Life of Christ, although some minor details, like the boys climbing trees in the Entry to Jerusalem, are tolerated. The Harrowing of Hell was not an episode witnessed or mentioned by any of the Four Evangelists but was approved by the Church, and the Lamentation of Christ, though not specifically described in the Gospels, was thought to be implied by the accounts there of the episodes before and after. Vernacular art was less policed by the clergy, and works such as some medieval tiles from Tring can show fanciful apocryphal legends that either hardly ever appeared in church art, or were destroyed at some later date.[7]

By the Gothic period the selection of scenes was at its most standardized. Emile Mâle's famous study of 13th-century French cathedral art analyses many cycles, and discusses the lack of emphasis on the "public life [which] is dismissed in four scenes, the Baptism, the Marriage at Cana, the Temptation and the Transfiguration, which moreover it is rare to find all together".[8]

Cycles

Early Christian art contains a number of narrative scenes collected on sarcophagi and in paintings in the Catacombs of Rome. Miracles are very often shown, but the Crucifixion is absent until the 5th century, when it originated in Palestine, soon followed by the Nativity in much the form still seen in Orthodox icons today. The Adoration of the Magi and the Baptism are both often found earlier, but the choice of scenes is very variable.

The only Late Antique monumental cycles to have survived are in mosaic: Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome has a cycle from 432–430 on the birth and infancy of Christ together with other scenes from the Life of the Virgin, the dedicatee of the church.[9] Sant'Appollinare Nuovo in Ravenna has cycles on opposite walls of the Works and Passion of Christ from the early 6th century. The Passion is notable for still not containing, among its thirteen scenes, a Crucifixion, and the Works contains eight miracles in its thirteen scenes. Neither of these features was to be typical of later art, but they are comparable to features of cycles in smaller objects of the period such as carved caskets and a gold pendant medallion of the late 6th century.[10]

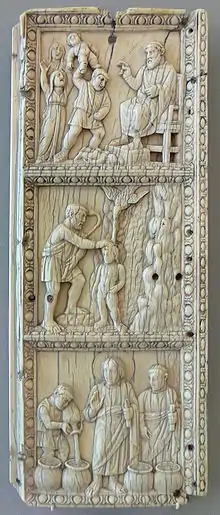

For the rest of the Early Medieval period illuminated manuscripts contain the only painted scenes to have survived in quantity, though many scenes have survived from the applied arts, especially ivories, and some in cast bronze. The period of Christ's Works still seems relatively prominent compared to the High Middle Ages.[11]

Although this was the period when the Gospel book was the main type of manuscript to receive lavish illumination in this period, the emphasis was on depicting Evangelist portraits, and relatively few contained narrative cycles; these are in fact more common in psalters and other types of book, especially from the Romanesque period. Where there were cycles of illustrations in illuminated manuscripts, these were normally collected together at the start of the book, or of the Gospels, rather than appearing throughout the text at the relevant places, something hardly found in Western manuscripts at all, and slow to develop in printed bibles. In the East this was more common; the 6th-century Byzantine Sinope Gospels has an unframed miniature at the bottom of every surviving page, and this style of illustrating the Gospels continued to be found in later Greek Gospel books, compelling the artist to devote more pictures to the Works. Scenes with miracles were more often found in cycles of the life of Saint Peter and other apostles, from late antique sarcophagi[12] to the Raphael Cartoons.

In painting, the Life was often shown on one side of a church, paired with Old Testament scenes on the other, the latter usually chosen for pre-figuring the New Testament scene according to the theory of typology. Such schemes were later called the Poor Man's Bible (and in book form the Biblia Pauperum) by art historians, and were very common, though most have now vanished. After stained-glass became important in Gothic art, this medium was also used, usually with a small medallion for each scene, requiring a very compressed composition. The frescos on the walls of the Sistine Chapel showing the Lives of Christ and Moses are an unusual variant.[13]

From the 15th century prints had first scenes, then whole cycles, which were also one of the most common subjects for blockbooks. Albrecht Dürer produced a total of three print cycles of the Passion of Christ: large (7 scenes before 1500, with a further 5 in 1510) and small (36 scenes in 1510) cycles in woodcut,[14] and one in engraving (16 scenes, 1507–1512).[15] These were distributed all over Europe, and often used as patterns by less ambitious painters. Hans Memling's Scenes from the Passion of Christ and Advent and Triumph of Christ are examples of a large number of scenes, in these case over twenty, shown in a single bird's eye view image of Jerusalem; another is illustrated here.

In Protestant areas production of paintings of the Life stopped very soon after the Reformation, but prints and book illustrations were acceptable, as free from the suspicion of idolatry. Nonetheless, there were surprisingly few cycles of the Life. Lucas Cranach the Elder made a famous propaganda set of the Passion of Christ and Antichrist (1521), where 13 matched pairs of woodcuts contrasted a scene from the Life with an anti-Catholic scene. But otherwise scenes from the Old Testament and parables were more often seen.

Parables

Of the thirty or so parables of Jesus in the canonical Gospels, four were shown in medieval art almost to the exclusion of the others, but not normally mixed in with the narrative scenes of the Life, though the page from the Eadwine Psalter (Canterbury, mid 12th century) illustrated here provides an exception to this. These were: the Wise and Foolish Virgins, Dives and Lazarus, the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan.[16] The Labourers in the Vineyard also appear in Early Medieval works.

From the Renaissance the numbers shown widened slightly, and the three main scenes of the Prodigal Son – the high living, herding the pigs, and the return – became the clear favourites. Albrecht Dürer made a famous engraving of the Prodigal Son amongst the pigs (1496), a popular subject in the Northern Renaissance, and Rembrandt depicted the story several times, although in at least one of his works, The Prodigal Son in the Tavern, a portrait of himself "as" the Son, revelling with his wife, is like many artists' depictions, a way of dignifying a genre merry company or tavern scene.[17] His late Return of the Prodigal Son (1662, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg[18]) is one of his most popular works.

Individual cycles with articles

.jpg.webp)

- St. Augustine Gospels, Italian, about 600, now only a quarter survives. Many miracles.

- Castelseprio

- Codex Aureus of Echternach, 11th-century Ottonian gospel book, with some 60 scenes, including many parables

- St. Albans Psalter, cycle of 40 images, mostly full-page. The Nativity story has 7 scenes, and from the Annunciation to the Return from Egypt takes 13.

- Eadwine Psalter, English manuscript of the mid-12th century, the prefatory cycle now dispersed

- Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto, a large combined Life of Christ and of the Virgin in fresco with nearly forty narrative scenes.

- Life of Christ (Giotto), a series of small panel paintings attributed to Giotto

- Life of Christ (circle of Cimabue?), a series of small panel paintings speculatively attributed to the circle of Cimabue

- Maestà (Duccio), a large combined Life of Christ and of the Virgin with nearly fifty scenes in total, on both sides of a panel altarpiece.

- Vyšší Brod (Hohenfurth) cycle, 9 panels, Bohemian Gothic

- Walls of the Sistine Chapel, by a team of masters, including Botticelli and Perugino

- Raphael Cartoons tapestry designs for the Sistine Chapel, a cycle of the lives of saints Peter and Paul, with some scenes from the Life of Christ (see also the Brancacci Chapel by Masaccio)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Schiller, I, 152

- ↑ Schiller has sections on each of these, and many other less common subjects. Mâle's Chapter 2 analyses 13th-century French Cathedral scenes in the text, and an appendix listing the contents of many.

- ↑ Hall, James, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 127, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0719539714

- ↑ Schiller, I, 152–3

- ↑ Lewine, Carol F.; JSTOR Vulpes Fossa Habent or the Miracle of the Bent Woman in the Gospels of St. Augustine, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge,

- ↑ Demus, Otto, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice (1 volume version, edited by Herbert L. Kessler), 48–50, University of Chicago Press, 1988, ISBN 0-226-14292-2

- ↑ Tring tile, Victoria & Albert Museum]

- ↑ Mâle, 177

- ↑ Schiller, II, 26–7

- ↑ Schiller, I, 153. The medallion was found at Adana and is in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, Inv. no 82.

- ↑ Schiller, I, 154

- ↑ Dick Stracke. "Miracles, Augusta State University". Aug.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ "Vatican Museums". Mv.vatican.va. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Kurth, Willi. The Complete Woodcuts of Albrecht Durer, Dover Books, New York, 1963. All images at Harvard external link.

- ↑ Strauss, Walter L. The Complete Engravings, Etchings and Drypoints of Albrecht Durer, Dover Books, New York, 1972

- ↑ Mâle, 195

- ↑ Gerard van Honthorst

- ↑ Return of the Prodigal Son

References

- G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, p. 56 & figs, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II,1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, figs 471–75, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, English translation of 3rd ed, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions), ISBN 978-0064300322

External links

- The Romanesque cycle in the St Albans Psalter

- The Passion Cycle in the English Parish Church

- Thesis on the cycle in the Avila Bible by Monica Ann Walker-Vadillo File size 6.5MB

- Dürer's three print Passion cycles from Harvard Art Museum

- Christian Iconography from Augusta State University – see under Jesus Christ, after alphabet of saints