| Leadhillite | |

|---|---|

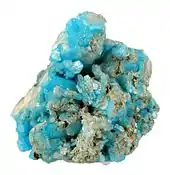

Thin crystals of transparent leadhillite, inside a vug of galena which seems to be partially altered to cerussite. From the type locality, Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland. Size: 5.3 x 5.1 x 4.4 cm. | |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate minerals |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Pb4SO4(CO3)2(OH)2 |

| IMA symbol | Lhl[1] |

| Strunz classification | 5.BF.40 |

| Dana classification | 17.1.2.1 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/a |

| Unit cell | a = 9.11, b = 20.82 c = 11.59 [Å]; β = 90.46°; Z = 8 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 1,078.90 g/mol |

| Colour | Colourless to white, grey, yellowish, pale green to blue |

| Crystal habit | Usually pseudo-hexagonal, thin to thick tabular {001} with hexagonal outline |

| Twinning | Commonly twinned, twin plane {140} |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {001} |

| Fracture | Irregular to conchoidal |

| Tenacity | sectile |

| Mohs scale hardness | 2+1⁄2 to 3 |

| Lustre | Adamantine, resinous, pearly |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 6.55 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (-) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.87, nβ = 2.00, nγ = 2.01 |

| Birefringence | 0.140 |

| 2V angle | 10° |

| Dispersion | Strong, r<v |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | Yellowish fluorescence in LW or SW UV |

| Solubility | Soluble in HNO3 |

| Alters to | Galena, calcite and susannite may alter to leadhillite. Leadhillite may alter to cerussite, calcite and susannite |

| Other characteristics | Not radioactive |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Leadhillite is a lead sulfate carbonate hydroxide mineral, often associated with anglesite. It has the formula Pb4SO4(CO3)2(OH)2.[6] Leadhillite crystallises in the monoclinic system, but develops pseudo-hexagonal forms due to crystal twinning. It forms transparent to translucent variably coloured crystals with an adamantine lustre. It is quite soft with a Mohs hardness of 2.5[6] and a relatively high specific gravity of 6.26 to 6.55.

It was discovered in 1832 in the Susannah Mine, Leadhills in the county of Lanarkshire, Scotland. It is trimorphous with susannite and macphersonite (these three minerals have the same formula, but different structures). Leadhillite is monoclinic, susannite is trigonal and macphersonite is orthorhombic.[2][3][5] Leadhillite was named in 1832 after the locality.[2][3][5]

Unit cell

Leadhillite belongs to the monoclinic crystal class 2/m, which is the class with the highest symmetry in the monoclinic system. It has a two-fold axis of symmetry perpendicular to a mirror plane, and the general form is an open-ended prism. The space group is P21/a, meaning that the two-fold axis is a screw axis and the mirror plane is a glide plane.[2][3][4][5] There are 8 formula units per unit cell (Z = 8) and the angle β is very nearly equal to 90°. The side-lengths of the unit cell are a = 9.11 Å, b = 20.82 Å and c = 11.59 Å.[7]

Structure

Leadhillite has a layered structure. The mineral contains both carbonate and sulfate groups, and these are arranged in separate sheets. Pairs of carbonate sheets 8(PbCO3) alternate with pairs of sulfate sheets 8[Pb(SO4)0.5OH]. The carbonate sheets virtually have trigonal symmetry, but the sulfate sheets do not. All the lead (Pb) atoms in the carbonate sheets are surrounded by 9 oxygens from carbonate groups and by one hydroxyl from an adjacent sulfate sheet. The Pb atoms in the sulfate sheets are bonded to 9 or 10 oxygens.[7]

Appearance

Crystals are usually small to microscopic, and nearly always pseudo-hexagonal, being tabular with a hexagonal outline. Prismatic forms also occur. The simplest form with faces parallel to the b axis and cutting the a and c axes (represented as {101}) may develop. When it does it may be striated or curved. The colour is white or pale shades of green, blue or yellow, but the commonest is clear to white. Leadhillite is transparent to translucent, with a white streak and a resinous to adamantine lustre, pearly on faces parallel to the plane containing the a and b axes. Tabular forms of susannite are very similar.[2][3][4][5]

Optical properties

Leadhillite is biaxial (-) with the optical Z axis parallel to the crystallographic b axis, and the optical X axis inclined to the crystallographic c axis at an angle of -5.5°.[2][5]

The refractive indices are large, giving the mineral its high lustre, nα = 1.87, nβ = 2.00 and nγ = 2.01. Compare these values with that for ordinary window glass, which is only 1.5. The refractive index depends upon the direction of travel of light through the crystal. The maximum birefringence δ is the difference between the highest and the lowest values. For leadhillite δ = 0.140.[3][4]

An important characteristic of a biaxial material is the angle between the two optic axes, called the optic angle and designated 2V. It is possible to calculate this value from the refractive indices, and also to measure it. For leadhillite both the measured and calculated values of 2V are 10°.[3][4]

When the colour of the incident light is changed the refractive indices change, and so does the value of 2V. This effect is known as dispersion of the optic axes. In leadhillite this effect is strong, with 2V smaller for red light than for violet light (r < v).[2][5]

The mineral may fluoresce yellowish longwave or shortwave ultraviolet light.[2][3][4][5]

Physical properties

Leadhillite is a soft mineral, with hardness only 2+1⁄2 to 3, a little less than that of calcite. It breaks with an irregular to conchoidal fracture and it is somewhat sectile. That is, thin shavings can be pared off it. It is heavy, due to the lead content, with specific gravity 6.55, similar to other lead minerals such as cerussite (6.5) and anglesite (6.3).[3][5]

Cleavage is perfect on a plane perpendicular to the c crystal axis.[2][3]

The mineral is usually twinned, according to a variety of twin laws, forming contact, penetration and lamellar twins. The typical habit is platy or tabular pseudohexagonal cyclic twinned crystals.[8]

Leadhillite is soluble with effervescence in nitric acid HNO3, leaving lead sulfate.[2][3][5]

Occurrence

The type locality is the Susanna Mine at Leadhills, Strathclyde, Scotland, UK.[3]

Leadhillite is a secondary mineral found in the oxidised zone of lead deposits associated with cerussite, anglesite, lanarkite, caledonite, linarite and pyromorphite.[2][3][5] It may form pseudomorphs after galena or calcite, and conversely calcite and cerussite may form pseudomorphs after leadhillite.[2] Heating leadhillite causes it to reversibly transform into susannite.[3]

References

- ↑ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gaines, R. V., et al. (1997) Dana’s New Mineralogy, Eighth edition, Wiley ISBN 978-0471193104

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Leadhillite on Mindat.org

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Leadhillite data on Webmineral

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Leadhillite data in the Handbook of Mineralogy

- 1 2 Spencer, Leonard James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 320.

- 1 2 Giuseppetti, Mazzi, and Tadini (1990) The crystal structure of leadhillite, Pb4(SO4)(CO3)2(OH)2. Neues Jahrbuch fur Mineralogie, Monatshefte, 6:255–268

- ↑ Leadhillite on Mineral Galleries Archived 2005-10-29 at the Wayback Machine