| Battle of Vella Lavella | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

US troops on Vella Lavella, mid-September 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,588[1] | 700[2] – 1,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 killed[4] | Less than 150[5] to 200–300 killed[6] | ||||||

The Battle of Vella Lavella was fought from 15 August – 6 October 1943 between the Empire of Japan and the Allied forces from New Zealand and the United States at the end of the New Georgia campaign. Vella Lavella, an island located in the Solomon Islands, had been occupied by Japanese forces early during the war in the Pacific. Following the Battle of Munda Point, the Allies recaptured the island in late 1943, following a decision to bypass a large concentration of Japanese troops on the island of Kolombangara.

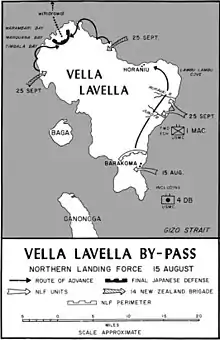

After a landing at Barakoma on 15 August, US troops advanced along the coasts, pushing the Japanese north. In September, New Zealand troops took over from the Americans, and they continued to advance across the island, hemming the small Japanese garrison along the north coast. On 6 October, the Japanese began an evacuation operation to withdraw the remaining troops, during which the Naval Battle of Vella Lavella was fought. Following the capture of the island, the Allies developed it into an important airbase which was used in the reduction of main Japanese base at Rabaul.

Background

The fighting on Vella Lavella took place following the Battle of Munda Point on New Georgia, which was fought in the aftermath of the Japanese evacuation from Guadalcanal as the Allies began advancing toward Rabaul under the Operation Cartwheel plan. After the loss of the airfield at Munda Field to US forces, the Japanese had withdrawn to Kolombangara, where they established a 10,000 to 12,000-strong garrison under Major General Noboru Sasaki. Initial US plans following Munda Point had envisaged an assault on Kolombangara, but the US commander, Admiral William Halsey, decided to bypass Kolombangara and land forces around Barakoma near the southeastern tip of the island of Vella Lavella instead where they were to capture the Japanese airfield and develop a naval base.[7]

Situated 35 nautical miles (65 km; 40 mi) northwest of Munda, Vella Lavella was the most northern island in the New Georgia chain and offered a stepping stone for future operations against Japanese forces on the Shortland Islands and on Bougainville. It also offered better prospects for base development than at Kolombangara. At the same time, it was close enough to US airbases at Munda and Sergei Point to afford the required air support that would be necessary to defend against Japanese air attack.[8]

In late July, a small reconnaissance party was dispatched to Vella Lavella, linking up with an Australian coastwatcher, a New Zealand missionary and several natives, to gather intelligence on Barakoma and the southeast coast.[9] These men and their native guides managed to explore the island for a full week, avoiding contact with the Japanese. On 31 July, they returned to Guadalcanal with thorough intelligence about the target. The village of Barakoma near the island's southeastern tip was selected as the landing place.[10]

On 12 August, an advanced party, consisting of naval and military personnel and a small group of troops from the 103rd Infantry Regiment, was sent from Guadalcanal and Rendova Island to Barakoma aboard four torpedo boats. En route, the boats were subjected to aerial attack which resulted in several casualties, but their crews were able to continue to their destination where they were met by a small group of natives in canoes. As reports were received about a larger-than-expected Japanese force near the landing beach, on 14 August this force was reinforced by more troops from the 103rd Infantry. The force was then tasked with marking and holding the beachhead for the assault force and for securing Japanese prisoners in the vicinity. They subsequently captured seven Japanese.[9] As of 15 August, there were 250 Japanese personnel present on Vella Lavella. These men were a mix of soldiers evacuated from New Georgia and sailors who had been stranded on the island.[11]

Battle

US troop landings

The initial landing on Vella Lavella was undertaken by a landing force of around 4,600 (rising to 5,800) US troops under Brigadier General Robert B. McClure. The main maneuver elements came from the 35th Regimental Combat Team.[12] This regiment was commanded by Colonel Everett E. Brown. It was drawn from the 25th Infantry Division, under Major General J. Lawton Collins, and formed part of Major General Oscar Griswold's XIV Corps. These troops landed on 15 August as part of an expeditionary force (designated Task Force 31) under the command of Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson, which embarked from Guadalcanal.[13] The expeditionary force consisted of a variety of vessels including: seven destroyer-transports, three LSTs, two submarine chasers and many LCIs. It was escorted by a destroyer screen of 12 ships, while P-40 and Corsair fighters patrolled the air above.[14][15]

%252C_USS_Chevalier_(DD-451)_and_USS_Taylor_(DD-468)_underway_at_sea_on_15_August_1943_(80-G-58800).jpg.webp)

The Japanese dispatched a large number of Zero fighters and Val dive-bombers in response to the landing. They attacked the LSTs around noon but were driven off by massed anti-aircraft fire. A further attempt late in the day was also spoiled. The returning Japanese aircraft were attacked by US Marine Corsairs that had been tasked to conduct a strafing mission around Kahili. In the early evening, a small group of Japanese torpedo aircraft unsuccessfully attacked the LCIs, while several seaplanes attacked the LSTs around midnight. Losses during these attacks were light for the Americans, with no ships being sunk and only two defending US aircraft being shot down, against Japanese losses of between 17 and 44 aircraft.[16]

Casualties during the initial landing amounted to 12 killed and 50 wounded for the Americans. After the initial fighting, the Americans established a beachhead and began resupply operations. Meanwhile, the Japanese decided against a counterattack, electing to evacuate the island instead. A barge depot was established for the evacuation at Horaniu, on the northeast coast of the island. A group of destroyers (Sazanami, Hamakaze, Shigure, and Isokaze, under Rear Admiral Matsuji Ijuin) sailed from Rabaul while a group of reinforcements was also dispatched to secure Horaniu.[17] These consisted of two companies of the 13th Infantry Regiment, with a combined strength of 390 soldiers, and a platoon of Special Naval Landing Force troops.[3][11]

.jpg.webp)

In response, four US destroyers (USS Nicholas, O'Bannon, Taylor and Chevalier) sailed from Purvis Bay under the command of Captain Thomas J. Ryan to disrupt the Japanese landing. Throughout 18 August, US and Japanese destroyers engaged each other off Horaniu, during which two Japanese destroyers were damaged and several smaller vessels destroyed. While this fighting was taking place at sea, the troop-laden Japanese barges made for the north coast, where they camouflaged themselves and hid. Their landing at Horaniu was completed the following day on 19 August. While the Japanese worked to establish their barge depot, two more echelons of US troops and supplies were dispatched for Barakoma, on 17 and 20 August respectively. These were subjected to further Japanese air attacks, during which LST-396 was lost and several other ships were damaged, including the destroyer USS Philip which accidentally collided with USS Waller.[18] Gordan Rottman has written that the Japanese force on Vella Lavella eventually reached 750 men.[11] Jon Diamond provides a higher figure, stating that 1,000 Japanese served on the island.[3]

While the main action occurred at sea and in the air, US troops ashore worked to improve the defenses around the beachhead and began limited patrol operations. In late August, a US reconnaissance patrol searching for a suitable location for a radar site discovered a strong concentration of Japanese troops around Kokolope Bay. McClure subsequently began an advance along the east coast of the island supported by native guides and a small group of Fijian scouts, aimed at capturing Kokolope Bay in order to establish the radar site. As the troops from the 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry pushed beyond their beachhead, a battalion of the 145th Infantry Regiment arrived from New Georgia to hold the perimeter. The 3rd Battalion, 35th Infantry and the 64th Field Artillery Battalion also joined the advance up the east coast. Several small scale skirmishes followed, but largely the Japanese sought to avoid decisive engagement. On 14 September, Horaniu was captured after the Japanese garrison withdrew to the northeast of the island.[19][20]

In the aftermath of the US advance, the Japanese troops began concentrating between Paraso Bay and Mundi Mundi.[21] Meanwhile, there were 121 Japanese air raids on Vella Lavella between 15 August and 6 October. The Marine 4th Defense Battalion provided defensive support during this time[21] and claimed to have shot down 42 Japanese aircraft.[22]

Relief by New Zealand troops

In mid-September, the Americans were relieved by New Zealanders from Major General Harold Barrowclough's 3rd Division.[23] The New Zealand 14th Brigade, consisting of around 3,700 men under Brigadier Leslie Potter,[24] used a series of amphibious operations and cross-country marches to advance through the coastal areas, bounding from bay to bay and then clearing each area with patrols. Two infantry battalions, the 35th and 37th, each allocated eight landing craft, conducted a pincer movement to trap the 600-strong Japanese garrison, while the 30th Infantry Battalion was held in reserve around the main concentration of troops in the south of the island.[25]

Departing from Maravari Beach on 21 September, the New Zealanders established their forward areas around Matu Soroto and Boro and then began their advance on 25 September. Over the course of ten days, the New Zealanders fought a series of minor actions as the 35th Infantry Battalion advanced up the western coast and the 37th moved up the east. During the advance, the terrain prevented the use of armour, while artillery had to be moved by landing craft and dragged ashore to support the infantry, which struggled to advance through the thick jungle amidst torrential rain. Progress was slow, and initially combat was confined to skirmishes against small groups of Japanese hiding in well concealed jungle positions.[26]

The 35th Battalion advanced to Pakoi Bay and then pushed overland towards Timbala Bay, where they planned to attack the main Japanese garrison which was withdrawing on both fronts. In doing so, several patrols were pushed forward to block suspected Japanese withdrawal routes towards Marquana Bay. These patrols were subsequently ambushed and cut off, after which two platoons were dispatched to rescue them. These also came up against strong opposition and forced to turn back and the decision was made to wait for the 37th Battalion to join the 35th before attacking. While they waited, further patrols were sent out and the ambushed patrols fought their way out from Japanese lines, having inflicted heavy casualties and were subsequently rescued by barge.[27]

Meanwhile, the 37th's advance had slowed due to the breakdown of many of its allotted landing craft. They subsequently had to borrow some of the craft allocated to the 35th Battalion, and supplemented these with a barge that was captured from the Japanese when a patrol boarded a vessel that had pulled into Tambana Bay. By 5 October they cleared Warambari Bay, amidst heavy fighting. The following day, the two New Zealand battalions were close to linking up, having squeezed the Japanese into a small pocket, which was reduced further when the 37th Battalion finally reached Mende Point on the afternoon of 6 October. A large scale attack was planned on the Japanese around Marziana Point and that night a heavy barrage was dialled in on the position. The appearance of Japanese aircraft, however, silenced the guns and throughout the night, the Japanese garrison was withdrawn from the island, replicating the withdrawal that had taken place from Kolombangara between 28 September and 4 October.[28][29]

Aftermath

Japanese withdrawal and casualties

During the night and early of the morning of 6–7 October, Rear Admiral Matsuji Ijuin led a force consisting of three destroyer transports and twelve small craft,[30] which was able to evacuate 589 personnel by sub chasers and transports from Marziana Point in Marquana Bay. A large naval battle subsequently took place north of Vella Lavella, as a group of six US destroyers engaged Ijuin's covering force.[6] For the loss of one destroyer, the Japanese transports were successful in evacuating the ground troops from Vella Lavella, while the US lost one destroyer sunk and two heavily damaged.[31]

The evacuated troops were disembarked at Buin, on Bougainville.[32] There, they joined many of the roughly 12,000 Japanese troops that had been withdrawn from Kolombangara; they would subsequently take part in the fighting on the island against Allied forces from late 1943 to 1945.[33] Casualties during the fighting around Vella Lavella during this phase of the campaign amounted to 150 US and New Zealand naval and military personnel killed.[4] The postwar official New Zealand history reports estimate Japanese casualties at between 200 and 300.[6] In contrast, Rottman has written that "less than 150" Japanese were killed.[5] The fighting on Vella Lavella took place concurrently with fighting on Arundel Island as US troops secured western New Georgia, which represented the end of the New Georgia campaign.[34] It was followed by operations to secure the Treasury Islands and the landings at Cape Torokina on Bougainville.[35]

Base development

Seabees of the 58th Naval Construction Battalion began landing on 15 August and set to work unloading the landing ships under frequent air attack. Among the first items unloaded were bulldozers, which were used to construct roads inland to sites where supplies could be dumped, dispersed away from the beach and each other. The Seebees built 9 miles (14 km) of roads during August. Their next task was the construction of a dispensary and an underground sick bay. An underground radio room was also built. The 4,000-by-200-foot (1,219 by 61 m) airstrip was surveyed and cleared during August, followed by the construction of the signal tower, operations room, avgas storage tanks and an accommodation camp for personnel in September. The first landing was made on the airstrip of 24 September. Work continued on developing the airbase into December, including the provision of an avgas tank farm with six 1,000-US-barrel (120,000 L; 31,000 US gal; 26,000 imp gal) tanks.[36] Vella Lavella became an important Allied airbase from which they were able to project air power towards Rabaul. It was the home base of Major Gregory Boyington's VMF-214, and other units.[37]

The channel through the reef was deepened to allow the passage of PT boats into the lagoon.[36] PT Squadron 11 established a base on the northeast coast of Vella Lavella on 25 September with seven PT boats and a small coastal transport.[38] A ramp was built for LSTs, and the jetty at Biloa was upgraded with the addition of an L-shaped end. This was subsequently improved by raising the surface, deepening the water, and adding pilings and ship camels. The 77th Naval Construction Battalion arrived on 25 September, in the midst of a Japanese air raid. During its tour on Vella Lavella, it would be bombed 47 times and suffer ten casualties. Its main task was the construction of hospital facilities with 1,000 beds for the upcoming Bougainville campaign. This included wards, operating rooms and administrative buildings. The 58th Naval Construction Battalion established a sawmill that produced 5,000 to 6,000 board feet (12 to 14 m3) of cut lumber per day. The 77th Naval Construction Battalion operated two more to satisfy the demands of the campaigns in the Treasury Islands and Bougainville. A detachment of the 53rd Naval Construction Battalion operated two more sawmills between November 1943 and January 1944.[36]

Two New Zealand field engineer companies (the 20th and 26th) were also sent to the island following the commitment of New Zealand troops. These worked alongside the Americans to improve roads and constructed several bridges.[39] The last of the US naval construction battalions left Vella Lavella in January 1944, and responsibility for the installations on Vella Lavella passed to the 502nd Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit (CBMU). Salvage operations commenced in May 1944, and the airstrip was abandoned on 15 June 1944. The final task was dismantlement of the tank farm. The 502nd CBMU then departed for Emirau Island on 12 July 1944.[36]

Notes

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel, p. 176; Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 128. Ground forces included 5,888 U.S. and 3,700 New Zealanders.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, pp. 128 & 139.

- 1 2 3 Diamond, The War in the South Pacific, p. 90.

- 1 2 Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 142. Includes ground force and naval support personnel.

- 1 2 Rottman, US Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle, p. 290

- 1 2 3 Gillespie, The Pacific, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 172–175, 185.

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 173.

- 1 2 Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Horton, New Georgia: Pattern for Victory, p. 130

- 1 2 3 Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II, p. 68

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 229; Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 176.

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 175–178.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 228–230.

- ↑ Horton, New Georgia: Pattern for Victory, p. 135

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 234–238.

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 183.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 233–239.

- 1 2 Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 126.

- ↑ Shaw and Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, p. 157

- ↑ Crawford, Kia Kaha, p. 150.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 127.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 130.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, pp. 133–136.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, pp. 136–138.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 229–243.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 243–250

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 251.

- ↑ Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 184–186.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 142.

- ↑ Newell, The Battle for Vella Lavella, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Bulkley, At Close Quarters, p. 135.

- ↑ Gillespie, The Pacific, p. 141.

References

- Bulkley, Robert J. Jr. (1962). At Close Quarters: PT Boats in the United States Navy. Washington: Naval History Division. OCLC 4444071. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- Bureau of Yards and Docks (1947). Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940-1946, Volume II. US Government Printing Office. OCLC 816329866. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Crawford, John, ed. (2000). "A Campaign on Two Fronts: Barrowclough in the Pacific". Kia Kaha: New Zealand in the Second World War. Auckland: Oxford University Press. pp. 140–162. ISBN 978-0-19-558455-4.

- Diamond, Jon (2017). The War in the South Pacific. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-7064-2.

- Gillespie, Oliver (1952). The Pacific. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War, 1939–1945. Wellington: War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs. OCLC 491441265.

- Horton, D. C. (1971). New Georgia: Pattern for Victory. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-34502-316-2.

- Miller, John Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. VI. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-1307-1.

- Newell, Reg (2016). The Battle for Vella Lavella: The Allied Recapture of Solomon Islands Territory, August 15 – September 9, 1943. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7327-4.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). US Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939–1945. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31906-8.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Anderson, Duncan (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-870-0.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Isolation of Rabaul. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Vol. II. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47282-447-9.

Further reading

- Craven, Wesley Frank; Care, James Lea. The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. IV. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-10. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons. World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- McGee, William L. (2002). "Occupation of Vella Lavella". The Solomons Campaigns, 1942–1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville—Pacific War Turning Point. Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: BMC Publications. ISBN 978-0-9701678-7-3.

- Rentz, John (1952). Marines in the Central Solomons. Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

External links

- Hughes, Warwick; Ray Munro. "3rd NZ Division in the Pacific". Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.