| Battle of Blackett Strait | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

Track chart of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3 cruisers, 3 destroyers | 2 destroyers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

2 destroyers sunk, 174 killed [1] 2 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Blackett Strait (Japanese: ビラ・スタンモーア夜戦 (Battle of Vila–Stanmore)) was a naval battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought on 6 March 1943 in the Blackett Strait, between Kolombangara and Arundel Island in the Solomon Islands. The battle was a chance encounter between two Japanese destroyers that had been undertaking a resupply run to Vila and a U.S. Navy force of three light cruisers and three destroyers that had been tasked with bombarding the Japanese shore facilities around Vila. The two forces clashed as the Japanese destroyers were withdrawing through the Kula Gulf. In the short battle that followed the two Japanese destroyers were sunk, after which the U.S. ships completed their bombardment of Vila before returning to their base.

Background

After the American victory in the Guadalcanal campaign in early 1943, operations in the Solomon Islands shifted to the west, where the Japanese maintained a substantial garrison on Kolombangara. Airbases had been established at Munda on the western coast of New Georgia and at Vila on the southern coast of Kolombangara. Allied efforts to reduce these airbases initially focused on air strikes but later included naval bombardment in preparation for a ground campaign to capture New Georgia that would eventually commence in late June and early July 1943. Meanwhile, the Japanese continued to build up these bases as part of their efforts to reinforce the southern defenses to their main base around Rabaul.[2][3]

On the night of 5 March 1943, the Japanese destroyers Murasame and Minegumo took supplies to the Japanese base at Vila.[4] Together, these ships formed part of the 2nd Fleet's Destroyer Squadron 4, which was under the command of Captain Masao Tachibana.[5] Their passage to Vila was undertaken through the Vella Gulf and Blackett Strait, while they decided to return to the Shortland Islands via the shorter route through the Kula Gulf.[6]

Order of Battle

| US Task Force MIKE[7] | |

| Ship | Commander |

|---|---|

| 3 Cleveland-class light cruisers | |

| USS Montpelier (F) | Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill Capt. Leighton Wood |

| Cleveland | Capt. Edmund W. Burrough |

| Denver | Capt. Robert B. Carney |

| 3 Fletcher-class destroyers | |

| USS Conway (F) | Comdr. Harold F. Pullen Lt. Comdr. Nathaniel S. Prime |

| Cony | Lt. Comdr. Harry D. Johnston |

| Waller | Comdr. Laurence H. Frost |

| Japan Destroyer Squadron 4[5][8] | |

| Ship | Commander |

|---|---|

| Shiratsuyu-class Murasame (DD)(F) | Capt. Masao Tachibana Lt. Comdr. Yoji Tanegashima |

| Asashio-class Minegumo (DD) | Lt. Comdr. Yoshitake Uesugi |

Battle

As the Japanese ships withdrew through the Kula Gulf after landing their cargo, they encountered Task Force 68 (TF 68), consisting of three light cruisers (USS Montpelier, Cleveland, and Denver) and three destroyers (USS Conway, Cony, and Waller) commanded by Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill. This force was en route to commence bombarding Japanese positions at Vila. Two submarines, Grayback and Grampus, had been assigned to support Merrill's force and were stationed along likely Japanese withdrawal routes out of the Kula Gulf. Merrill's attack on Vila was timed to coincide with another attack on Munda by four destroyers under Captain Robert Briscoe.[4]

.jpg.webp)

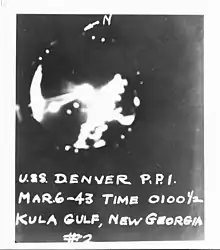

In a short battle, both Japanese destroyers were sunk. The U.S. force was proceeding in a southwesterly direction about 2 miles (3.2 km) off the New Georgia coast, cruising at about 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). Meanwhile, the Japanese ships were sailing in the opposite direction along the east coast of Kolombangara, northeast from Sasamboki Island, roughly offshore from Stanmore. First contact was established by the U.S. radar operators around 00:57 on 6 March and firing commenced at 01:01. The U.S. cruisers engaged to starboard with their 6-inch guns at a range of around 11,000 yards (10,000 m).

Radar-controlled gunnery was in its infancy as a technique and there was a tendency for the initial barrage to fall on the same, usually nearest, target. In earlier naval battles in the Pacific, this tactical deficiency had allowed the Japanese to successfully engage attacking U.S. ships with torpedoes and had resulted in several losses for U.S. forces previously.[4][9] In this case, the entire opening salvo straddled Murasame. As Minegumo's captain began passing orders to his crew, Murasame was hit by the sixth salvo of American gunfire, which was followed shortly afterwards by a salvo of five torpedoes that had been fired by the destroyer Waller. At around 01:15, one of these torpedoes hit Murasame, which exploded, caught fire and eventually sank. The explosion was reportedly heard by Briscoe's force about 25 miles (40 km) away around Munda.[10] The U.S. cruisers then rapidly shifted target, doing so before Minegumo could release any torpedoes.[9]

Meanwhile, Minegumo attempted to return fire, aiming for the flashes of the U.S. gun batteries off their starboard bow. After a few minutes, though, the second Japanese destroyer was also hit and began sinking in short order. As the surviving Japanese crew abandoned ship, firing ceased at 01:14. After the engagement, the U.S. vessels completed a turn to starboard when they were roughly due east of the Blackett Strait and north of Tunguirili Point. At 01:24, they commenced a northerly bombardment run off the Kolombangara coast, having been delayed by only 16 minutes. Under the direction of a reconnaissance aircraft flying overhead, the U.S. gunners targeted "supply dumps, runways, bivouacs and dispersed aircraft", according to Samuel Morison. The bombardment was reportedly very destructive and accurate. Several Japanese shore batteries responded by firing on the bombarding ships but were knocked out quickly with counter-battery fire. After completing their task at 01:40, Merrill's force withdrew through the New Georgia Sound.[11]

Aftermath

A total of 174 Japanese sailors lost their lives during the battle on 6 March; 128 of these were from Murasame, while the rest were from Minegumo. The survivors swam to shore on Kolombangara. Fifty-three survivors from Murasame and 122 from Minegumo managed to reach Japanese lines. Two other survivors from Minegumo were later captured by U.S. forces.[1][12] One of the U.S. submarines assigned to support the operation, Grampus, went missing and did not return to base at the end of its patrol. The submarine's fate remains unknown, and it is uncertain if it was lost as a result of actions during the Blackett Strait operation or before. It was officially listed as missing, presumed lost on or before 3 March although there is a possibility it was attacked by Minegumo during the evening of 5/6 March.[4][13]

Mining operations

On 20 March, the Allies began mining operations in the central Solomons using U.S. Navy and Marine Corps torpedo bombers to sow mines throughout the northern Solomons.[9] After a month, these operations were briefly suspended as a result of Operation I-Go to free up AirSols aircraft to respond in the event of further attacks. In May, these operations resumed. On 7 May, the minelayers USS Gamble, Breese, and Preble, escorted by Radford, laid mines across Blackett Strait in an attempt to interdict Japanese ships traveling through the strait. The next day, the Japanese destroyers Oyashio, Kagero, and Kuroshio all hit mines in that area. Kuroshio sank immediately. Kagero and Oyashio sank later that day after being attacked and further damaged by U.S. aircraft from Henderson Field following a radio report from an Australian coastwatcher on Kolombangara.[14]

PT-109

Later in the year, with the ground campaign around Munda reaching a climax, another engagement occurred in Blackett Strait when a force of 15 PT boats, including Lieutenant (Junior Grade) John F. Kennedy's PT-109 were sent to intercept the "Tokyo Express" supply convoy on 2 August. In what National Geographic called a "poorly planned and badly coordinated" attack, 15 boats with 60 available torpedoes went into action. However, of the 30 torpedoes fired by PT boats from four sections, not a single hit was scored.[15] In the battle, only four PT boats (the section leaders) had radar, and they were ordered to return to base after firing their torpedoes on radar bearings. When they left, the remaining boats were virtually blind.[16][17]

Patrolling just after the section leader had departed for home, PT-109 was run down on a dark moonless night by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, returning from the supply mission.[18] The PT boat had her engines at idle to hide her wake from seaplanes.[19] Conflicting statements have been made as to whether the destroyer captain spotted and steered towards the boat. Members of the destroyer crew believed the collision was not an accident, though other reports suggest Amagiri's captain had not intentionally rammed PT-109.[20] Kennedy's crew was assumed lost by the U.S. Navy[21] but were found later by Solomon Islander scouts Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana.[22]

Notes

- 1 2 Nevitt, Allyn D., Combinedfleet.com. Murasame & Minegumo. Retrieved 5 June 2020

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 106

- ↑ Stille 2018, backcover & p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Morison 1958, p. 107.

- 1 2 Muir, Dan. "Battle of Blackett Strait, 6 March 1943". NavWeaps. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ ONI 1944, p. 34.

- ↑ Senshi Sōsho (40), p. 206a, select "115" on web page.

- 1 2 3 "Central Solomons campaign". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 110.

- ↑ "Grampus V (SS-207)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 112–115.

- ↑ Donovan 2001, pp. 95–99.

- ↑ "John F. Kennedy and PT-109". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ↑ Roos, David. "The Navy Disaster That Earned JFK Two Medals for Heroism". History.com. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ↑ Donovan 2001, pp. 73, 100–107.

- ↑ Donovan 2001, pp. 60–61, 100.

- ↑ Donovan 2001, pp. 105, 108–109.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (16 August 2014). "Eroni Kumana, Who Saved Kennedy and His Shipwrecked Crew, Dies at 96". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

References

- Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-914-X.

- Crenshaw, Russell Sydnor (1998). South Pacific Destroyer: The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-136-X.

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. ISBN 0-8159-5302-X.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253018779.

- Donovan, Robert J. (2001) [1961]. PT-109: John F. Kennedy in WW II (40th Anniversary ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-137643-7.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Hara, Tameichi (1961). Japanese Destroyer Captain. New York & Toronto: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-27894-1.

- Hove, Duane T. (2003). American Warriors: Five Presidents in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Burd Street Press. ISBN 1-57249-260-0.

- Kilpatrick, C. W. (1987). Naval Night Battles of the Solomons. Exposition Press. ISBN 0-682-40333-4.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 6. Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1307-1.

- Office of Naval Intelligence, United States Navy, ed. (1944). Bombardments of Munda and Vila-Stanmore, January-May 1943. Combat Narratives: Solomon Islands Campaign. Vol. IX.

- Roscoe, Theodore (1953). United States Destroyer Operations in World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-726-7.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47282-447-9.

- Office of War History, National Institute for Defense Studies (December 1970). 『南太平洋陸軍作戦<3> ムンダ・サラモア』 [Army Operation in the South Pacific (3) Munda-Solomons]. Senshi Sōsho (in Japanese). Vol. 40. Tokyo: Asagumo Shinbunsha.