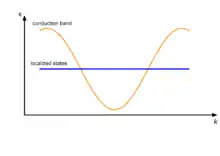

In solid-state physics, Kondo insulators (also referred as Kondo semiconductors and heavy fermion semiconductors) are understood as materials with strongly correlated electrons, that open up a narrow band gap (in the order of 10 meV) at low temperatures with the chemical potential lying in the gap, whereas in heavy fermion materials the chemical potential is located in the conduction band. The band gap opens up at low temperatures due to hybridization of localized electrons (mostly f-electrons) with conduction electrons, a correlation effect known as the Kondo effect. As a consequence, a transition from metallic behavior to insulating behavior is seen in resistivity measurements. The band gap could be either direct or indirect. Most studied Kondo insulators are FeSi, Ce3Bi4Pt3, SmB6, YbB12, and CeNiSn, although there are over a dozen known Kondo insulators.[1]

Historical overview

In 1969, Menth et al. found no magnetic ordering in SmB6 down to 0.35 K and a change from metallic to insulating behavior in the resistivity measurement with decreasing temperature. They interpreted this phenomenon as a change of the electronic configuration of Sm.[2]

Gabriel Aeppli and Zachary Fisk found a descriptive way to explain the physical properties of Ce3Bi4Pt3 and CeNiSn in 1992. They called the materials Kondo insulators, showing Kondo lattice behavior near room temperature, but becoming semiconducting with very small energy gaps (a few Kelvin to a few tens of Kelvin) when decreasing the temperature.[3]

Transport properties

At high temperatures the localized f-electrons form independent local magnetic moments. According to the Kondo effect, the dc-resistivity of Kondo insulators shows a logarithmic temperature-dependence. At low temperatures, the local magnetic moments are screened by the sea of conduction electrons, forming a so-called Kondo resonance. The interaction of the conduction band with the f-orbitals results in a hybridization and an energy gap . If the chemical potential lies in the hybridization gap, an insulating behavior can be seen in the dc-resistivity at low temperatures.

In recent times, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy experiments provided direct imaging of band-structure, hybridization and flat band topology in Kondo insulators and related compounds.[4]

References

- ↑ Dzero, Maxim; Xia, Jing; Galitski, Victor; Coleman, Piers (2016-03-10). "Topological Kondo Insulators". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 7 (1): 249–280. arXiv:1506.05635. Bibcode:2016ARCMP...7..249D. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031214-014749. ISSN 1947-5454. S2CID 15794370.

- ↑ Menth, A.; Buehler, E.; Geballe, T. H. (17 February 1969). "Magnetic and Semiconducting Properties of SmB6". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 22 (7): 295–297. Bibcode:1969PhRvL..22..295M. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.22.295. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Kondo Insulators, G. Aeppli, Z. Fisk, 1992, Comments Cond. Mat. Phys. 16, 155-170

- ↑ Hasan, M. Zahid; Xu, Su-Yang; Neupane, Madhab (2015), "Topological Insulators, Topological Dirac semimetals, Topological Crystalline Insulators, and Topological Kondo Insulators", Topological Insulators, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 55–100, doi:10.1002/9783527681594.ch4, ISBN 978-3-527-68159-4

- Coleman, P. (2007). "Heavy Fermions: Electrons at the edge of magnetism". Handbook of magnetism and advanced magnetic materials. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons. arXiv:cond-mat/0612006. Bibcode:2006cond.mat.12006C. ISBN 9780470022177. OCLC 124165851.

- Riseborough, Peter S. (2000). "Heavy fermion semiconductors". Advances in Physics. Informa UK Limited. 49 (3): 257–320. Bibcode:2000AdPhy..49..257R. doi:10.1080/000187300243345. ISSN 0001-8732. S2CID 119991477.