The Knights of Honor (K. of H.), was a fraternal order and secret society in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century. The Knights were one of the most successful fraternal beneficiary societies of its time.[1]

History

The origin of the order goes back to disputes in the state of Kentucky among members of the Order of United American Mechanics and the Ancient Order of United Workmen in Kentucky in the early 1870s. Dr. Darius Wilson was a Louisville physician and avid fraternalist. In addition to being a Freemason and an Oddfellow, in 1872 he was elected State Council Secretary for OUAM of Kentucky. According to his own account, his work leading the OUAM made him so well known that he was approached by the leadership of the AOUW to help organize lodges for that Order as well. After being initiated in 1873 by Grand Master Workman Handy and the Grand Lodge of Kentucky, Dr. Wilson successfully organized Louisville Lodge #6, the sixth lodge of the order in Kentucky, with twenty four of Louisville's most prominent citizens as members and himself as Master Workman.[2]

While Dr. Wilson was studying the ritual of the AOUW he learned the national leadership of the OUAM had refused to charter a new Council of its youth affiliate, the Junior Order of United American Mechanics because they had adopted the name "Robert E. Lee". After becoming aware of this "intolerance", Dr. Wilson resigned as Secretary of the Kentucky Council and withdrew from the Order. A local chapter of the JOUAM had also surrendered its charter in protest over the senior Orders actions. This posed a problem, as the members of the Junior Order were only eighteen to twenty ones years old and none of the existing fraternal orders would accept them, other than a few temperance groups. At the request of Council president J . A. Demaree, Dr. Wilson drew up a constitution and helped the Council reorganize as the Gold Lodge #1, Knights of Honor at a meeting held on June 30, 1870.[3]

Dr. Wilson never intended to create further lodges of the Knights of Honor and was devoting his time to the organizing more lodges of the AOUW when his commission from the latter was revoked on October 24, 1873. That night Grand Master Workman Handy went to Louisville Lodge #6 and had charges drawn up against him for creating a new fraternal order and copying the AOUWs constitution. A committee was set up to investigate the charges. According to Wilson, the members of this committee were, like him, also Freemasons and Oddfellows, and could see that the constitution of the AOUW was a copy of the constitution of the Oddfellows Grand Lodge of Ohio, itself a copy of the constitution of a Masonic Grand Lodge.[4]

Grand Master Workman Hardy maintained that the creation of a rival order while holding a commission from the AOUW was a breach of trust on the part of Dr. Wilson. Other have questioned whether the constitutions and laws were essentially those of the Oddfellows or Masons.[5]

In any event, Dr. Wilson ignored Hardy's opposition, abandoned his medical practice and devoted his energies to organizing the Knights of Honor. The meeting he had called to organize Lodge #8 of the AOUW, he instead made Louisville Lodge #2 of the Knights. By his own account he secured all the members and organized 80 of the first 81 lodges. He also tried early on to get the group on a graded assessment formula. However, his associates disagreed, feeling that people would not want to join an order that charged more than the $1 flat assessment and wanted to set the age limit for membership at 44. A compromise was reached with all members under 44 paying the $2 flat assessment rate and a graded assessment for ages 44 to 45.[6]

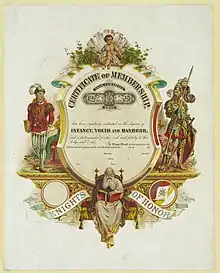

Sick benefits were paid out by the local lodges, but death benefits were managed by the Supreme Lodge. Members could buy certificates of $500, $1000 or $2000 plus assessments. The Knights differed from other orders such as the AOUW by using a graded assessment plan for its death benefits. Members between 45 and 55 paid more than those between 21 and 45. Soon the society admitted men 18 to 21 years old and expanded its graded assessment plan for all new members under the age of 45. By the mid 1890s, however, it became clear that this system of paying a fixed assessment year after year, based on the date the member joined the society would eventually be "found wanting". After prolonged investigation the Knights adopted a new insurance system with each age paying a different rate of assessment from 18 to 61, the effect being that each member in any one year would only pay out the benefits for the other members his age based on mortality tables.[7]

Unfortunately, when the Knights changed to a more actuarially sound financial basis in 1895 membership declined as insurance began to cost more. The group disbanded in 1916.[8]

Organization

The Knights were organized along the same three tier structure as most fraternal orders of the era. Local groups were "Subordinate Lodges", state or regional groups were "Grand Lodges" and the national authority was the "Supreme Lodge". In 1896 the Knights had thirty six Grand Lodges and 2,600 Subordinate Lodges with an average of fifty members each[9] By 1910, however, the number of Subordinate Lodges was down to 1,234. The national headquarters of the organization was in St. Louis, Missouri.[10]

Membership

Membership was open all acceptable white men of good moral character, who believed in God, were of good bodily health and able to support themselves and their family.[11] In 1875, the Supreme Lodge created a female auxiliary called the Degree of Protection open to the wives, mothers, sisters and unmarried daughters of the Knights, as well as males who were already members of the Knights of Honor. However in the years that followed only a few Lodges of this degree were created and in 1877 the Supreme Lodge abolished the degree. Thereafter, representatives of the degree met in Louisville and organized a new society, the Order of Mutual Protection of the Knights and Ladies of Honor, subsequently known as the Knights and Ladies of Honor.[12]

The Knights were founded by an original group of 17 men in 1873 and increased to 99 by the end of the year. By the end of 1874 it had increased to 999 members. The group was hit hard by the yellow fever epidemic of 1875–1878. In 1878 alone, the order had to pay out $385,000 for death benefits for 193 members.[13] Despite this, the Knights disbursed large sums of money to suffers of the yellow fever who were not members of the order.[14] Over the next 18 years, the order steadily increased its membership, reaching 126,000 in 1895. That year, as stated, the group changed from the graded assessment program to a more actuarially sound one, causing costs to go up and membership began to decline.[15] There were 96,000 members in 1897 and 90,335 in 1898.[16]

Ritual

Unlike most fraternal orders of its day,[17] the Knights of Honor did not require prospective members to swear an oath in the initiation rite, but merely to promise to obey the rules of the order and "protect a worthy brother in his adversities and afflictions". The secrecy of the order was declared to be only that which was necessary to keep "intruders and unworthy men" from gaining benefits.[18]

References

- ↑ Alvin J. Schmidt Fraternal Orders (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 1930, p.178

- ↑ Sackett, Myron Ward, 1841-Early history of fraternal beneficiary societies in America Meadville, Pa., The Tribune publishing company p.220

- ↑ Sackett pp.220-1

- ↑ Sackett pp.221-2

- ↑ Sackett pp.222-3

- ↑ Sackett p.222

- ↑ Stevens, Albert Clark, 1854- The Cyclopædia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Authentic Information and the Results of Original Investigation as to More than Six Hundred Secret Societies in the United States (New York: Hamilton Printing and Publishing Company), 1899, p.146

- ↑ Schmidt p.179

- ↑ Stevens p.147

- ↑ Frank Wilson Blackmar ed. Kansas; a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. ... with a supplementary volume devoted to selected personal history and reminiscence Chicago, Standard publishing company Vol. II p.79

- ↑ Stevens p.146

- ↑ Stevens p.147

- ↑ Stevens p.146

- ↑ Blackmar p.79

- ↑ Stevens p.147

- ↑ Schmidt p.179

- ↑ Schmidt p.178

- ↑ Stevens p.147

Further reading

- O'Donnell, Terence History of Life Insurance Chicago : American Conservation Company, 1936.