| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Draco |

| Right ascension | 18h 57m 44.03831s[1] |

| Declination | +49° 18′ 18.4965″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 13.9[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | F9 IV/V[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −15.54±2.91[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −4.350(12) mas/yr[1] Dec.: −3.256(14) mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 1.1695 ± 0.0112 mas[1] |

| Distance | 2,790 ± 30 ly (855 ± 8 pc) |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.2±0.1[4] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.2±0.1[4] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 1.7[1] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.4[4] cgs |

| Temperature | 6,080+260 −170[4] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.12±0.18[4] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 4.6±2.1[4] km/s |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| KIC | data |

Kepler-90, also designated 2MASS J18574403+4918185, is a G-type star located about 2,790 light-years (855 pc) from Earth in the constellation of Draco. It is notable for possessing a planetary system that has the same number of observed planets as the Solar System.

Nomenclature and history

Prior to Kepler observation, Kepler-90 had the 2MASS catalogue number 2MASS J18574403+4918185. It has the designation of KIC 11442793 in the Kepler Input Catalog, and was given the Kepler object of interest number of KOI-351 when it was found to have a transiting planet candidate.[5]

The star's planetary system was discovered by NASA's Kepler Mission, a mission tasked with discovering planets in transit around their stars.[4] The transit method that Kepler uses involves detecting dips in brightness in stars. These dips in brightness can be interpreted as planets whose orbits move in front of their stars from the perspective of Earth. The name Kepler-90 derives directly from the fact that the star is the catalogued 90th star discovered by Kepler to have confirmed planets.[6]

The whole star and planet system is designated by just "Kepler-90", without a postfix, with Kepler-90A specifically referring only to the star, if needed for clarity. The first planet discovered is Kepler-90b, with subsequently discovered planets given subsequent lowercase letters in order of discovery, up to Kepler-90i, for the last planet found to date.[7][lower-alpha 1]

Stellar characteristics

Kepler-90 is likely a G-type star that is approximately 120% the mass and radius of the Sun. It has a surface temperature of around 6,100 K.[4] In comparison, the Sun has a surface temperature of 5,772 K.[8]

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 14.[2][9] It is too dim to be seen with the naked eye, which typically can only see objects with a magnitude around 6.[10]

Planetary system

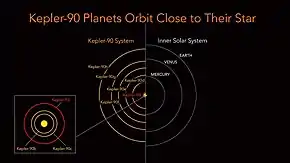

Kepler-90 is notable for similarity of the configuration of its planetary system to that of the Solar System, in which rocky planets are nearer the star and gas giants farther away. The six inner planets range from super-Earths to mini-Neptunes in size. The two outermost planets are gas giants. The most distant known planet orbits its host star at about the same distance as Earth from the Sun.

Kepler-90 was used to test the "validation by multiplicity" confirmation method for Kepler planets. Six inner planets met all the requirements for confirmation. The penultimate planet showed transit-timing variations, indicating that it is a real planet as well.[11]

On 14 December 2017, NASA and Google announced the discovery of an eighth exoplanet, Kepler-90i, in the Kepler-90 system. The discovery was made using a new machine learning method developed by Google.[12][13]

The Kepler-90 system is one of only two eight-planet candidate systems from Kepler, together with Kepler-385, and the second to be discovered after the Solar System. It was also the only seven-planet candidate system from Kepler before the eighth was discovered in 2017. All of the eight known planet candidates orbit within about 1 AU of Kepler-90. A Hill stability test and an orbital integration of the system show that it is stable.[14]

The five innermost exoplanets, Kepler-90b, c, i, d, and e may be tidally locked, meaning that one side of the exoplanets permanently faces the star in eternal daylight and the other side permanently faces away in eternal darkness.

A 2020 analysis of transit-timing variations of the two outermost planets, Kepler-90g and h, found best-fit masses of 15+0.9

−0.8 M🜨 and 203±5 M🜨, respectively. Given a transit-derived radius of 8.13 R🜨, Kepler-90g was found to have an extremely low density of 0.15±0.05 g/cm3, unusually inflated for its mass and insolation. Several possible explanations for its apparently low density include a puffy planet with a dusty atmosphere or a smaller planet surrounded by a tilted wide ring system (albeit the latter option is less likely due to the lack of evidence for rings in transit data).[15]

.

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | — | 0.074 ± 0.016 | 7.008151 | — | 89.4° | 1.31 R🜨 |

| c | — | 0.089 ± 0.012 | 8.719375 | — | 89.68° | 1.18 R🜨 |

| i | — | 0.107 ± 0.03 | 14.44912 | — | 89.2° | 1.32 R🜨 |

| d | — | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 59.73667 | — | 89.71° | 2.88 R🜨 |

| e | — | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 91.93913 | — | 89.79° | 2.67 R🜨 |

| f | — | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 124.9144 | 0.01 | 89.77° | 2.89 R🜨 |

| g | 15+0.9 −0.8 M🜨 |

0.71 ± 0.08 | 210.60697 | 0.049+0.011 −0.017 |

89.92+0.03 −0.01° |

8.13 R🜨 |

| h | 203 ± 5 M🜨 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 331.60059 | 0.011+0.002 −0.003 |

89.927+0.011 −0.007° |

11.32 R🜨 |

Near resonances

Kepler-90's eight known planets all have periods that are close to being in integer ratio relationships with other planets' periods; that is, they are close to being in orbital resonance. The period ratios b:c, c:i and i:d are close to 4:5, 3:5, and 1:4, respectively (4: 4.977, 3: 4.97, and 1: 4.13) and d, e, f, g, and h are close to a 2:3:4:7:11 period ratio (2: 3.078: 4.182: 7.051: 11.102; also 7: 11.021).[11][12] f, g, and h are also close to a 3:5:8 period ratio (3: 5.058: 7.964).[4]

Relevant to systems like this and that of Kepler-36, calculations suggest that the presence of an outer gas giant planet (as exemplified by g and h in this system) facilitates the formation of closely packed resonances among inner super-Earths.[18] The semimajor axis of any additional nontransiting outer gas giant must be larger than 30 AU to keep from perturbing the observed planetary system out of the transiting plane.[19]

See also

- TRAPPIST-1, star with seven known exoplanets

- HD 10180, star with at least six known exoplanets, and three exoplanet candidates

- Kepler-385, star with at least three known exoplanets, and five more candidates

- HD 219134, star with six exoplanets

- 55 Cancri, star with multiple planets

- Tau Ceti, star with at least four exoplanets and four more candidates

Footnotes

- ↑ Designations with postfix letters b, c, d, e, f, g, h, and i follow the order of discovery; postfix letter A (Kepler-90A) is used for the host star (or often no suffix at all, Kepler-90, which also refers to the entire system of star and planets as a whole). The letter b specifies the first planet discovered orbiting a given star, followed by the other lowercase letters of the alphabet.[7] In the case of the Kepler-90 star system, there have been eight planets discovered orbiting the star Kepler-90A, so far, so letters up to i are used to distinguish them, with Kepler-90i being the last planet discovered thus far.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- 1 2 Zacharias, N.; Finch, C. T.; Girard, T. M.; Henden, A.; Bartlett, J. L.; Monet, D. G.; Zacharias, M. I. (2012). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: UCAC4 Catalogue (Zacharias+, 2012)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: I/322A. Originally Published in: 2012yCat.1322....0Z; 2013AJ....145...44Z. 1322. Bibcode:2012yCat.1322....0Z.

- ↑ Gray, R. O.; Corbally, C. J.; De Cat, P.; Fu, J. N.; Ren, A. B.; Shi, J. R.; Luo, A. L.; Zhang, H. T.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y. (2016). "LAMOST Observations in the Kepler Field: Spectral Classification with the MKCLASS Code". The Astronomical Journal. 151 (1): 13. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...13G. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/1/13. S2CID 126346435.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cabrera, J.; Csizmadia, Sz.; Lehmann, H.; Dvorak, R.; Gandolfi, D.; Rauer, H.; et al. (31 December 2013). "The planetary system to KIC 11442793: A compact analogue to the Solar System". The Astrophysical Journal. 781 (1): 18. arXiv:1310.6248. Bibcode:2014ApJ...781...18C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/781/1/18. S2CID 118875825.

- 1 2 "Kepler-90". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- ↑ "Kepler numbers". NASA Exoplanet Archive. Pasadena, CA: California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- 1 2 Hessman, F.V.; Dhillon, V.S.; Winget, D.E.; Schreiber, M.R.; Horne, K.; Marsh, T.R.; et al. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ↑ Williams, D.R. (1 July 2013). "Sun Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "Planet Kepler-90 b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ Sinnott, Roger W. (19 July 2006). "What's my naked-eye magnitude limit?". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- 1 2 Lissauer, Jack J.; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Bryson, Stephen T.; Rowe, Jason F.; Jontof-Hutter, Daniel; Agol, Eric; Borucki, William J.; Carter, Joshua A.; Ford, Eric B.; Gilliland, Ronald L.; Kolbl, Rea; Star, Kimberly M.; Steffen, Jason H.; Torres, Guillermo (25 February 2014). "Validation of Kepler's multiple planet candidates. II: Refined statistical framework and descriptions of systems of special interest". The Astrophysical Journal. 784 (1): 44. arXiv:1402.6352. Bibcode:2014ApJ...784...44L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/784/1/44. S2CID 119108651.

- 1 2 3 Shallue, Christopher J.; Vanderburg, Andrew (16 December 2017). "Identifying exoplanets with deep learning: A five planet resonant chain around Kepler-80 and an eighth planet around Kepler-90" (PDF). Retrieved 14 December 2017 – via Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

- ↑ Chou, Felicia; Hawkes, Alison; Landau, Elizabeth (14 December 2017). "Artificial intelligence, NASA data, used to discover eighth planet circling distant star" (Press release). JPL / NASA. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Schmitt, J.R.; Wang, J.; Fischer, D.A.; Jek, K.J.; Moriarty, J.C.; Boyajian, T.S.; et al. (26 June 2014). "Planet hunters. VI. An independent characterization of KOI-351 and several long period planet candidates from the Kepler archival data". The Astronomical Journal. 148 (28): 28. arXiv:1310.5912. Bibcode:2014AJ....148...28S. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/148/2/28. S2CID 119238163.

- 1 2 Liang, Yan; Robnik, Jakob; Seljak, Uros (2021). "Kepler-90: Giant transit-timing variations reveal a super-puff". The Astronomical Journal. 161 (4): 202. arXiv:2011.08515. Bibcode:2021AJ....161..202L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abe6a7. S2CID 226975548.

- ↑ "Kepler-90". Open Exoplanet Catalog. MIT. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "New Worlds Atlas". Exoplanets.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Hands, T.O.; Alexander, R.D. (13 January 2016). "There might be giants: Unseen Jupiter-mass planets as sculptors of tightly packed planetary systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 456 (4): 4121–4127. arXiv:1512.02649. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456.4121H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2897. S2CID 55175754.

- ↑ Becker, Juliette C.; Adams, Fred C. (2017). "Effects of unseen additional planetary perturbers on compact extrasolar planetary systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 468 (1): 549–563. arXiv:1702.07714. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.468..549B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx461. S2CID 119325005.