| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

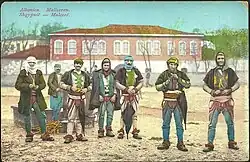

Kelmendi is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region in Malësia (Kelmend municipality) and eastern Montenegro (parts of Gusinje Municipality). It is located in the upper valley of the Cem river and its tributaries in the Accursed Mountains range of the Dinaric Alps. The Vermosh river springs in the village of the same name, which is Albania's northernmost village. Vermosh pours into Lake Plav.

Kelmendi is mentioned as early as the 14th century and as a territorial tribe it developed in the 15th century. In the Balkans, it is widely known historically for its longtime resistance to the Ottoman Empire and its extensive battles and raids against the Ottomans which reached as far north as Bosnia and as far east as Bulgaria. By the 17th century, they had grown so much in numbers and strength that their name was sometimes used for all tribes of northern Albania and Montenegro. The Ottomans tried several times to expel them completely from their home territory and forcefully settle them elsewhere, but the community returned to its ancestral lands again and again.

Kelmendi's legacy is found throughout the region. Kelmendi is found beyond the Cem valley (Selcë, Vukël, Nikç and others), Gusinje (in particular, the villages Vusanje, Doli, Martinovići and Gusinje itself) and Plav (Hakaj) to the east in Rožaje and the Pešter plateau. In Kosovo, descendants of Kelmendi live in the Rugova Canyon and western Kosovo mainly. In Montenegro, half of the tribe (pleme) of Old Ceklin and a part of Kuči which settled there in the 16th century come from Kelmendi. The northernmost settlement from Kelmendi is in the villages of Hrtkovci and Nikinci in Syrmia when 1,600 Catholic Albanian refugees settled there in 1737.

Name

A folk etymology explains it as Kol Mendi. The historical origin of the toponym is traced to the Roman fort of Clementiana which Procopius of Caesarea mentions in the mid 6th century in the road that connected Scodra and Petrizên. As a surname it first appears in 1353 in a Latin document which mentions dominus Georgius filius Georgii Clementi de Spasso (Lord Georgius, son of Georgius Clementi of Spas) in northern Albania.[1]

Geography

The Kelmendi region is located in the District of Malësi e Madhe in northern Albania, situated in the northernmost and most isolated part of the country. It borders the Albanian tribal regions of Gruda to the west, Hoti to the southwest, Boga to the south, Shala to the east, and the Montenegrin tribal regions of Kuči and Vasojevići to the north.

History

Early

There are many theories on the place of origin of the Kelmendi. Before the 20th century, several travellers, historians and clergymen have recorded various oral traditions and presented their own interpretations. In modern times, archival research has provided a more historically grounded approach. Milan Šufflay in the 1920s found the first reference to the Kelmendi name in the Venetian archives. The publication of the Ottoman defter of the sanjak of Scutari in 1974 marks the publication of the first historical record about the people of Kelmendi, their anthroponymy, toponymy and social organization.

In the early centuries of Kelmendi, in the 15th and 16th centuries the only information that is mentioned about them is their language, ethnic group and religion. As Catholic bishop Frang Bardhi writes in his correspondence with the Roman Curia, they belong to the Albanian nation, speak Albanian, hold our holy Roman Catholic beliefs.[2] The first writing about Kelmendi's area of origin is from Franciscan missionary, Bernardo da Verona who in 1663 wrote that it is not easy to make comments about Kelmendi's origin, but it has become customary to say that they came from Kuči or one of the neighbouring tribes.. The second commentary about Kelmendi's place of origin comes in 1685 in a letter by Catholic archbishop Pjetër Bogdani who writes that according to oral stories the progenitor of Kelmendi came from the Upper Morača.[3]

French consul Hyacinte Hecquard (1814–1866), noted that all of the Kelmendi (Clementi) except the families called Onos believe that they descend from one ancestor, Clemens or Clement (Kelment or Kelmend[4] in Albanian).[5] A Franciscan priest in Shkodra, Gabriel recounted a story about a Clemens who was a Venetian who was a priest in Venetian Dalmatia and Herzegovina before taking refuge in Albania.[6] The story went on to say he originated from either of those two provinces, and that he was encountered by a pastor in Triepshi.[6]

Johann Georg von Hahn recorded the most widely spread oral tradition about Kelmendi's origins in 1850. According it a rich herdsman in the region of Triepshi (which administratively in the past fell within Kuci) employed as a herdsman a young man who came to Triepshi from an unknown region. The young man had an affair with Bumçe, the daughter of the rich herdsman. When she became pregnant, the two were married but because their affair was punishable by customary law they left the area and settled to the south in the present Kelmendi area.[7] Their seven sons are the historical ancestors of the settlements of Kelmendi in Albania and the Sandžak.[8] Kola, the eldest is the founder of Selcë. Johan Georg von Hahn placed the settlement of Kelmendi's progenitor in Bestana, southern Kelmend.

Yugoslav anthropologist Andrija Jovićević recorded several similar stories about their origin. One story has it that the founder settled from Lajqit e Hotit, in Hoti, and to Hoti from Fundane, the village of Lopare in Kuči; he was upset with the Hoti and Kuči, and therefore left those tribes. When he lived in Lopare, he married a girl from Triepshi, who followed him. His name was Amati, and his wife's name was Bumçe. According to others, his name was Klement, from where the tribe received its name. Another story, which Jovićević had heard in Selce, was that the founder was from Piperi, a poor man that had worked as a servant for a wealthy Kuči, there he sinned with a girl from a noble family, and left via the Cem.[9]

In oral tradition, Bumçe, the wife of Kelmendi came from the Bekaj brotherhood of Triepshi.[10]

The first historical record about Kelmendi is the Ottoman defter of the sanjak of Scutari 1497, which was a supplementary registry to that of 1485. The defter of households and property was initially carried out in 1485, but Kelmendi doesn't appear in the registry as they resisted the entry of the Ottoman soldiers in their lands.[11] It had 152 households in two villages divided in five pastoral communities (katund). The katund of Liçeni lived in the village of Selçisha, while the other four (Leshoviq, Muriq, Gjonoviq, Kolemadi) lived in the village of Ishpaja.[12] The heads of the five katunds were: Rabjan son Kolë (Liçeni), Marash son of Lazar (Gjonoviq), Stepan son of Ulgash (Muriq), Lulë son Gjergj (Kolemadi).[12] Kelmendi was exempted from almost all taxes to the new central authorities. Of the five katuns of Kelmendi, in four the name Kelmend appears as a patronym (Liçeni, Gjonoviq, Leshoviq, Muriq), an indication of kinship ties between them. The leader of Liçeni in Selca Rabjan of Kola recalls the oral tradition of the son Kelmend, Kola who founded Selca and who had three sons: Vui, Mai and Rabin Kola.

The katun that was spelled as Kolemadi in the defter belongs to the historical tribe of Goljemadhi that became part of Kelmendi.

In the Ottoman register of the area of Corinth (southern Greece), there are two Albanian villages called Kelmendi. Their names indicate that the settlers who founded them came from the region of Kelmendi.[13]

Ottoman

The self-governing rights of northern Albanian tribes like Kelmendi and Hoti increased when their status changed from florici to derbendci, which required mountain communities to maintain and protect land routes, throughout the countryside, which connected regional urban centres. In return they were exempted from extraordinary taxes. The Kelmendi were to guarantee safe passage to passengers in the route from Shkodra to western Kosovo (Altun-ili) and that which passed through Medun and reached Plav.[14][12]

As early as 1538, the Kelmendi rose up against the Ottomans again and appear to have done so also in 1565 as Kuči and Piperi were also in rebellion.[15][16] The 1582–83 defter recorded the nahiya of Clementi with two villages (Selca and Ishpaja) and 70 households.[17] The katunds of the previous century had either settled permanently or moved to other areas like Leshoviq which moved northwards and settled in Kuči.[17] Thus, the population in Kelmendi was less than half in 1582 in comparison to 1497. Anthroponymy remained roughly the same as in 1497 as most names were Albanian and some showed Slavic influence.[17][18] In the mid-1580s, the Kelmendi seemed to have stopped paying taxes to the Ottomans.[15] They had by this time gradually come to dominate all of northern Albania.[15] They were mobile and went raiding in what is today Kosovo, Bosnia, Serbia and even as far as Plovdiv in Bulgaria.[15]

Venetian documents from 1609 mention the Kelmendi, the tribes of the Dukagjin highlands and others as being in a conflict with the Ottomans for 4 consecutive years.[19] The local Ottomans were unable to counter them and were thus forced to ask the Bosnian Pasha for help.[19]

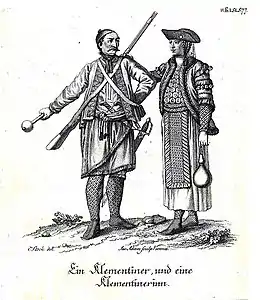

Kelmendi was very well known in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries because of it constant rebellion against the Ottomans. This caused the name of Kelmendi to be used as a synonym for all Albanian and Montenegrin tribes of the Ottoman borderlands as they were the best known community of that region to outsiders. Thus, Marino Bizzi (1570–1624), the Archbishop of Bar writes in 1610 that the Kelmendi peoples, who are almost entirely Latin, speak Albanian and Dalmatian and are divided in ten katuns: Kelmendi, Gruda, Hoti, Kastrati, Shkreli, Tuzi all Latins and Bjelopavlici, Piperi, Bratonosici, these are Dalmatians and Kuci of whom half are schismatics and half Latin.[20]

In 1613, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the rebel tribes of Montenegro. In response, the tribes of the Vasojevići, Kuči, Bjelopavlići, Piperi, Kastrati, Kelmendi, Shkreli and Hoti formed a political and military union known as “The Union of the Mountains” or “The Albanian Mountains”. The leaders swore an oath of besa to resist with all their might any upcoming Ottoman expeditions, thereby protecting their self-government and disallowing the establishment of the authority of the Ottoman Spahis in the northern highlands. Their uprising had a liberating character. With the aim of getting rid of the Ottomans from the Albanian territories[21][22] Bizzi reported an incident in 1613 in which an Ottoman commander, Arslan Pasha, raided the villages of the Kelmendi and started taking prisoners, until an agreement was reached with the Kelmendi clans. According to the agreement, the Kelmendi would surrender fifteen of their members as slaves, and pay a tribute of 1,000 ducats to the Ottomans. However, as Arslan Pasha waited for the payment of the tribute, the Kelmendi ambushed part of his troops and killed about thirty cavalrymen. After this incident the Ottoman troops retreated to Herceg Novi (Castelnuovo).[23] Mariano Bolizza recorded the "Climenti" in his 1614 report as being a Roman rite village, describing them as "an untiring, valorous and extremely rapacious people", with 178 houses, and 650 men in arms commanded by Smail Prentashev and Peda Suka.[24] In 1614, they, along with the tribes of Kuči, Piperi and Bjelopavlići, sent a letter to the kings of Spain and France claiming they were independent from Ottoman rule and did not pay tribute to the empire.[25][26]

Clashes with the Ottomans continued through the 1630 and culminate in 1637-38 where the tribe would repel an army of 12,000 (according to some sources 30,000) commanded by Vutsi Pasha of the Bosnia Eyalet.

According to Albanian bishop Frang Bardhi writing in 1638, the Kelmendi tribe grew very rich by attacking and stealing merchandise from Christian merchants in Albania, Bosnia and Serbia, killing those who resisted them.[27] After merchants travelled to Constantinople, and representative of the local population of Novi Pazar and northern Kosovo sent a petition, to complain about Klemendi raids and ask for protection,[28][29] the Sultan ordered Vučo Pasha, the Pasha of Bosnia, to lead the 1638 Ottoman expedition against Kelmendi.[30]

According to Bardhi after being ambushed by the tribe in the mountains and suffering heavy casualties the Ottoman force returned to Bosnia.[29] Robert Elsie calls Bardhi's report a "glorified text about the Kelmendi tribe".[29] The legend of Nora of Kelmendi would come to life during this epic struggles.[31]

According to French historian Ernest Lavisse and to François Lenormant, in 1638 Sultan Mourad IV asked Doudjé-Pasha, the governor of Bosnia, to lead a punitive expedition, in the heart of winter, against the Kelmendi. The tribe weakened by famine and lacking ammunition, put up a desperate defense, rolling huge blocks of rock from the tops of the mountains onto the Turkish army. The death of their knèze Vokodoud, killed in a fight, and a few days after that of the Voivode Hotasch, whom the Pasha himself surprised by climbing an inaccessible peak with crampons, deprived the Clementi of their best chiefs and determined their submission,[32] the other Kelmendi leaders were decapitated by the Ottomans and their heads sent to the Sultan.[31]

When Pasha of Herzegovina attacked city of Kotor 1657, Albanian tribes of Kelmendi and Bjelopavlići also participated in this battle[33]

In the Cretan War the Kelmendi played a tactical role between the Ottomans and the Venetians.[34] In 1664, Evliya Çelebi mentioned Kelmendi Albanians among the "infidel warriors" he saw manning Venetian ships in the harbour of Split. The Kelmendi promised support to whichever side would fulfil their requests. in 1666, for instance some of the Kelmendi supported the Ottomans on condition that they be exempted from paying tribute for five years. Some of them also converted to Islam.[35]

In 1651, they aided the army of Ali-paša Čengić, which attacked Kotor; the army raided and destroyed many monasteries in the region.[36] In 1658, the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Kelmendi, Hoti and Gruda allied themselves with the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called "Seven-fold barjak" or "alaj-barjak", against the Ottomans.[37]

The Kelmendi appear in a report of 1671 written by the apostolic visitor Stefano Gaspari. According to the report, the Kelmendi had constructed a church dedicated to Saint Clement in the settlement of Speia di Clementi (Ishpaja) 20 years earlier in 1651, that was used by the entire tribal community to attend mass and receive the holy sacrament. Gaspari also reports that the Kelmendi were primarily concentrated in the following villages: Morichi (Muriqi) with six households and 40 inhabitants; Genovich (Gjonoviq or Gjenoviq) with seven households and 60 inhabitants; Lesovich (Leshoviq) with 15 households and 120 inhabitants; Melossi with seven households and 40 inhabitants; Vucli (Vukël) with 32 households and 200 inhabitants; Rvesti with six households and 30 inhabitants; Zecca (Zeka) with seven households and 40 inhabitants; Selza di Clementi (Selcë) with 28 households and 250 inhabitants; and the villages of Rabiena and Radenina which, together, had 60 households and 400 inhabitants. However, it is also reported that the Kelmendi had come to occupy and absorb the plateau of Nixi (Nikç) and Roiochi, which collectively had 112 households and 660 inhabitants, following a series of incursions and attacks on the local population.[38]

In 1685, Süleyman, sanjak-bey of Scutari, annihilated the bands of Bajo Pivljanin that supported Venice at the Battle on Vrtijeljka.[39] Süleyman was said to have been aided by the Brđani (including the Kelmendi[36]), who were in feud with the Montenegrin tribes.[40] The Kelmendi lived off of plundering. Plav, Gusinje, and the Orthodox population in those regions suffered the most from the Kelmendi's attacks.[40] The Kelmendi also raided the Pejë area, and they were so powerful there that some villages and small towns paid them tribute.[40] In March 1688, Süleyman attacked the Kuči tribe;[41] the Kuči, with help from Kelmendi and Piperi, destroyed the army of Süleyman twice, took over Medun and got their hands of large quantities of weapons and equipment.[37] In 1692, Süleyman defeated the Montenegrins at Cetinje, once again with the help of the Brđani.[40]

In 1689 the Kelmendi volunteered in the Imperial Army of the Holy Roman Empire during the Kosovo campaign. Initially they were serving Süleyman, but after negotiations with a Venetian official, they abandoned the Ottoman ranks.[42] In October 1689, Arsenije III Čarnojević allied himself with the Habsburgs, gaining the title of Duke. He met up with Silvio Piccolomini in November, and put under his wings a large army of Serbs, including some Kelmendi. However, Noel Malcolm does not support this statement at all since he has found sources which confirms that, Arsenje III Čarnojevíc, did not meet with General Piccolomini in Kosovo, but instead Pjeter Bogdani did since he was there in the name of the Kelmendi army, he was then given the name Patriarch of Kelmendi, by the Habsburgs.[43] [44]

_7832.NEF_10.jpg.webp)

In 1700, the pasha of Pejë, Hudaverdi Mahmut Begolli, resolved to take action against the continuing Kelmendi depredations in western Kosovo. With the help of other mountain tribes, he managed to block the Kelmendi in their homelands, the gorge of the upper Cem river, from three sides and advanced on them with his own army from Gusinje, In 1702, having worn them down by starvation, he forced the majority of them to move to the Peshter plateau. Only the people of Selcë were allowed to stay in their homes. Their chief had converted to Islam, and promised to convert his people to. A total of 251 Kelmendi households (1,987 people) were resettled in the Pešter area on that occasion. Other were resettled in Gjilan, Kosovo. However five years later the exiled Kelmendi managed to fight their way back to their homeland, and in 1711 they sent out a large raiding force to bring back some other from Pešter too.[35]

In the 18th century, Hoti and Kelmendi assisted the Kuči and Vasojevići in the battles against the Ottomans; after that unsuccessful war, a part of the Kelmendi fled their lands.[45] After the defeat in 1737, under Archbishop Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta, a significant number of Serbs and Kelmendis retreated into the north, Habsburg territory.[46] Around 1,600 of them settled in the villages of Nikinci and Hrtkovci, where they later adopted a Croat identity.[47]

In ca. 1897, the Boga would become a fully integrated bajrak of the Kelmendi tribe.[48]

Modern

During the Albanian revolt of 1911 on 23 June Albanian tribesmen and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with three of the signatories being from Kelmendi.[49] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build one to two primary schools in the nahiye of Kelmendi and pay the wages of teachers allocated to them.[49]

On May 26, 1913, 130 leaders of Gruda, Hoti, Kelmendi, Kastrati and Shkreli sent a petition to Cecil Burney in Shkodër against the incorporation of their territories into Montenegro.[50] Baron Franz Nopcsa, in 1920, puts the Kelmendi as the first of the Albanian clans, as the most frequently mentioned of all.[51]

By the end of the Second World War, the Albanian Communists sent its army to northern Albania to destroy their rivals, the nationalist forces. The communist forces met open resistance in Nikaj-Mertur, Dukagjin and Kelmend, which were anti-communist. Kelmend was headed by Prek Cali. On January 15, 1945, a battle between the Albanian 1st Brigade and nationalist forces was fought at the Tamara Bridge. Communist forces lost 52 soldiers, while in their retaliation about 150 people in Kelmend people were brutally killed.[52] Their leader Prek Cali was executed.

This event was the starting point of other dramas, which took place during Enver Hoxha's dictatorship. Class struggle was strictly applied, human freedom and human rights were denied, Kelmend was isolated both by the border and by lack of roads for other 20 years, agricultural cooperative brought about economic backwardness, life became a physical blowing action etc. Many Kelmendi people fled, some others froze by bullets and ice when trying to pass the border.[53]

Tradition

During Easter processions in Selcë and Vukël the kore, a child-eating demon, was burnt symbolically.[54] In Christmas time alms were placed upon ancestors' graves. As in other northern Albanian clans the Kanun (customary law) that is applied in Kelmend is that of The Mountains (Albanian: Kanuni i Maleve).

Families

Kelmend

The region consists of six primary villages: Boga, Nikç, Selcë, Tamarë, Vermosh and Vukël, all part of the Kelmend municipality. In terms of historical regions, Kelmendi neighbours and Hoti neighbours are Kuči , to the west, and the Vasojevići to the north. In the late Ottoman period, the tribe of Kelmendi consisted of 500 Catholic and 50 Muslim households.[55] The following lists are of families in the Kelmend region by village of origin (they may live in more than one village):

- Hysaj

- Peraj

- Cali

- Racaj

- Lelçaj

- Lekutanaj

- Lumaj

- Macaj

- Mitaj

- Mernaçaj

- Naçaj

- Miraj

- Pllumaj

- Preljocaj (also Tinaj)

- Bujaj

- Selmanaj

- Shqutaj

- Vukaj

- Vuktilaj

- Vushaj

- Bardhecaj

- Pepushaj

- Vukel

- Nilaj

- Vucinaj

- Vucaj

- Mirukaj

- Gjikolli

- Drejaj

- Martini

- Aliaj

- Dacaj

- Gjelaj

- Nicaj

- Kajabegolli

- Delaj

- Smajlaj

- Preldakaj

- Nikçi

- Rukaj

- Gildedaj

- Prekelezaj

- Hasaj

- Nikac

- Kapaj

- Ujkaj

- Alijaj

- Hutaj

- Bikaj[53]

- Bakaj

- Rukaj

- Mernaçaj

- Lelcaj

- Vukaj

- Cekaj

- Tataj

- Lelcaj

- Selcë

- Lumaj

- Miraj

- Tinaj

- Mernaçaj

- Vushaj

- Pllumaj

- Vukaj

- Bujaj

- Hysaj

- Mitaj

- Tilaj

Montenegro

- Plav-Gusinje

- Ahmetaj or Ahmetović, in Vusanje. They descend from a certain Ahmet Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj and grandson of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Bacaj

- Balaj (Balić), in Grnčar. Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from the village of Vukël or Selcë in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year. The clan's closest relatives are the Balidemaj. Legend has it that the Balaj, Balidemaj and Vukel clans descended from three brothers. However, a member of the Vukel clan married a member of the Balić clan, later resulting in severed relations with the Vukel clan.

- Balidemaj (Bal(j)idemaj/Balidemić), in Martinovići. This branch of the clan remained Catholic for three generations, until Martin's great-grandson converted to Islam, taking the name Omer. Since then, the family was known as Omeraj. Until recently was the family's name changed to Balidemaj, named after Bali Dema, an army commander in the Battle of Novšiće (1789). The clan's closest relatives are the Balajt. Legend has it that the Balaj, Balidemaj and Vukel clans descended from three brothers.

- Bruçaj, they are descendants of a Catholic Albanian named Bruç Nrrelaj, son of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Cakaj

- Canaj, in the villages of Bogajići, Višnjevo and Đurička Rijeka. Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from the village of Vukël in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year.

- Çelaj, in the villages of Vusanje and Vojno Selo. Claims descendance from Nrrel Balaj. The Nikça family are part of the Çelaj.

- Dedushaj, in Vusanje. They are descendants of a Catholic Albanian named Ded (Dedush) Balaj, son of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukel in northern Albania.

- Berisha

- Hakaj, in Hakanje.

- Hasilović, in Bogajiće.

- Goçaj, in Vusanje.

- Gjonbalaj, in Vusanje, with relatives in Vojno Selo. Their ancestor, a Catholic Albanian named Gjon Balaj, immigrated with his sons: Bala, Aslan, Tuça and Hasan; along with his brother, Nrrel, and his children: Nika, Ded (Dedush), Stanisha, Bruç and Vuk from the village of Vukël in northern Albania to the village of Vusanje/Vuthaj in the late-17th century. Upon arriving, Gjon and his descendants settled in the village Vusanje/Vuthaj and converted to Islam and were known as the Gjonbalaj. Relatives include Ahmetajt, Bruçajt, Çelajt, Goçaj, Lekajt, Selimajt, Qosajt, Ulajt, Vuçetajt.

- Kukaj, in Vusanje

- Lecaj, in Martinovići. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Lekaj, in Gornja Ržanica and Vojno Selo. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Lekë Pretashi Nikaj.

- Martini, in Martinovići, GusinjeMartinovići. The eponymous founder, a Catholic Albanian named Martin, immigrated to the village of Trepča in the late 17th century from Selcë.

- Hasangjekaj, in Martinovići, GusinjeMartinovići. They descend from a Hasan Gjekaj from Vukël, a Muslim of the Martini clan.

- Prelvukaj, in Martinovići. They descend from a Prelë Vuka from Vukël, of the Martini clan.

- Musaj, Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from village Vukël in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year.

- Novaj

- Pepaj, in Pepići

- Rekaj, in Bogajići, immigrated to Plav-Gusinje circa 1858.

- Rugova, in Višnjevo with relatives in Vojno Selo and Babino Polje. They descend from a Kelmend clan of Rugova in Kosovo.

- Qosaj/Qosja (Ćosaj/Ćosović), in Vusanje. They are descendants of a certain Qosa Stanishaj, son of Stanisha Nrrelaj and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Selimaj,

- Smajić, in Novšići.

- Ulaj, in Vusanje. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Ulë Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj.

- Vukel, in Dolja. They immigrated to Gusinje in 1675 from the village of Vukël in northern Albania. A certain bey from the Šabanagić clan gave the clan the village of Doli. Also, they are ancestors of Shala brtherhood in Rugova.

- Vuçetaj (Vučetaj/Vučetović), in Vusanje. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Vuçetë Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj.

- Zejnelović in Gusinje, oral tradition shows that most Zejnelović migrated east to Rozhaje, and Kruševo

- Skadarska Krajina and Šestani

- Dabović, in Gureza, Livari and Gornji Šestani. Can be found in Shkodër. Their relatives are the Lukić clan in Krajina.

- Lukić - Related to the Dabović clan in Krajina.

- Radovići, in Zagonje.

- Elsewhere

The families of Dobanovići, Popovići and Perovići in Seoca in Crmnica hail from Kelmend.[56] Other families hailing from Kelmend include the Mujzići in Ćirjan, Džaferovići in Besa, and the Velovići, Odžići and Selmanovići in Donji Murići.[57] The Mari and Gorvoki families, constituting the main element of the Koći brotherhood of Kuči, hail from Vukël.[58]

In Rugova, Kosovo, the majority of the modern Albanian population descends from the Kelmendi. The Kelmendi fis in Rugova also include immigrant Shkreli, Kastrati and Shala families, but later is confirmed that Shala brotherhood is not related to that tribe, indeed they came from the Vukel brotherhood. A number of families of Kelmendi descent also live in Prizren and Lipjan. The oldest Kelmendi families in Rugova, the Lajqi, claim descent from a Nika who settled there.[59]

Notable people

- By birth

- Prek Cali (1872–1945), Kelmendi chieftain, rebel leader, World War II guerrilla. Born in Vermosh.

- Nora of Kelmendi (17th century), legendary woman warrior.

- By ancestry

- Ahmet Zeneli, Albanian freedom fighter. Born in Vusanje.

- Ali Kelmendi (1900–1939), Albanian communist. Born in Peja.

- Ibrahim Rugova, former President of Kosovo.[60] Born in Istok.

- Majlinda Kelmendi, Kosovo Albanian judoka, Born in Peja.

- Jeton Kelmendi, Kosovo Albanian writer. Born in Peja.

- Sadri Gjonbalaj, Montenegrin-born American footballer. Born in Vusanje.

- Bajram Kelmendi (1937–1999), Kosovan lawyer and human rights activist. Born in Peja.

- Aziz Kelmendi, Yugoslav soldier and mass murderer. Born in Lipljan.

- Faton Bislimi, Albanian activist. Born in Gjilan.

- Emrah Klimenta, Montenegrin football player.

References

- ↑ Milan Šufflay (2000). Izabrani politički spisi. Matica hrvatska. p. 136. ISBN 9789531502573. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ↑ Zamputi, Injac (1963). Relacione mbi gjendjen e Shqipërisë veriore e të mesme në shekullin XVII (1634-1650) [Correspondence on the situation in northern and central Albania in the 17th century]. University of Tirana. p. 161. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ↑ Ukgjini, Nikë (1999). "Vështrim i shkurtër historik për fisin e Kelmendit [A short historical summary about the fis of Kelmendi]". Phoenix Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, p. .

- ↑ Hecquard 1859, p. 177.

- 1 2 Hecquard 1859, p. 178.

- ↑ von Hahn, Johan Georg; Elsie, Robert (2015). The Discovery of Albania: Travel Writing and Anthropology in the Nineteenth Century. I. B. Tauris. pp. 120–22. ISBN 978-1784532925.

- ↑ Santayana, Manuel Pardo de; Pieroni, Andrea; Puri, Rajindra K. (2010-05-01). Ethnobotany in the new Europe: people, health, and wild plant resources. Berghahn Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84545-456-2. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ Jovićević 1923, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Shyti, Nikollë. "Të parët e Kelmendit erdhën nga Trieshi" (PDF). Zani i Malësisë [Voice of Malësia]. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ Pulaha, Selami (1974). Defter i Sanxhakut të Shkodrës 1485. Academy of Sciences of Albania. pp. 431–434. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 Pulaha, Selami (1975). "Kontribut për studimin e ngulitjes së katuneve dhe krijimin e fiseve në Shqipe ̈rine ̈ e veriut shekujt XV-XVI' [Contribution to the Study of Village Settlements and the Formation of the Tribes of Northern Albania in the 15th century]". Studime Historike. 12: 102. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ Machiel, Kiel (2016). "Corinth in the Ottoman period (1458-1687 and 1715-1821)". Shedet. 3 (3). doi:10.36816/shedet.003.05. S2CID 211648429.

- ↑ Kola, Azeta (2017). "FROM SERENISSIMA'S CENTRALIZATION TO THE SELFREGULATING KANUN: THE STRENGTHENING OF BLOOD TIES AND THE RISE OF GREAT TRIBES IN NORTHERN ALBANIA FROM 15TH TO 17TH CENTURY" (PDF). Acta Histriae. 25 (25–2): 361–362. doi:10.19233/AH.2017.18. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Elsie 2015, p. 28.

- ↑ Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Pulaha, Selami (1972). "Elementi shqiptar sipas onomastikës së krahinave të sanxhakut të Shkodrës [The Albanian element in view of the anthroponymy of the sanjak of Shkodra]". Studime Historike: 92. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ Vasić, Milan (1991), "Etnički odnosi u jugoslovensko-albanskom graničnom području prema popisnom defteru sandžaka Skadar iz 1582/83. godine", Stanovništvo slovenskog porijekla u Albaniji : zbornik radova sa međunarodnog naučnog skupa održanog u Cetinju 21, 22. i 23. juna 1990 (in Serbo-Croatian), OCLC 29549273

- 1 2 Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 98.

- ↑ Shkurtaj 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Kola, Azeta (January 2017). "From serenissima's centralization to the selfregulating kanun: The strengthening of blood ties and the rise of great tribes in northern Albania from 15th to 17th century". Acta Histriae. 25 (2): 349–374 [369]. doi:10.19233/AH.2017.18.

- ↑ Mala, Muhamet (2017). "The Balkans in the anti-Ottoman projects of the European Powers during the 17th Century". Studime Historike (1–02): 276.

- ↑ Elsie 2003, p. 159.

- ↑ Bolizza, Mariano. "Mariano Bolizza: Report and Description of the Sanjak of Shkodra (1614)" – via Montenegrina History.

- ↑ Kulišić, Špiro (1980). O etnogenezi Crnogoraca (in Montenegrin). Pobjeda. p. 41. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Lambertz, Maximilian (1959). Wissenschaftliche Tätigkeit in Albanien 1957 und 1958. Südost-Forschungen. S. Hirzel. p. 408. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, p. 31.

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 "Frang Bardhi: The Pasha of Bosnia attacks Kelmendi". Robert Elsie. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ↑ Winnifrith, T.J. (2021). Nobody's Kingdom: A History of Northern Albania. Andrews UK. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-909930-95-7. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- 1 2 François Lenormant (1866). Turcs et Monténégrins (in French). Paris: Didier. pp. 124–128. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Lavisse, E.; Rambaud, A. (1895). Histoire générale du IV siècle á nos jours: Les guerres de religion, 1559-1648 (in French). A. Colin. p. 2-PA894. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ↑ Tea Perinčić Mayhew (2008). Dalmatia Between Ottoman and Venetian Rule: Contado Di Zara, 1645-1718. p. 45.

- ↑ Galaty, Michael; Lafe, Ols; Lee, Wayne; Tafilica, Zamir (2013). Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1931745710. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- 1 2 Elsie 2015, p. 32.

- 1 2 Bartl, Peter (2007). Albania sacra: geistliche Visitationsberichte aus Albanien. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-447-05506-2. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- 1 2 Mitološki zbornik. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. pp. 24, 41–45.

- ↑ Gaspari, Stefano. "Stefano Gaspari: Travels in the Diocese of Northern Albania". Robert Elsie: Texts and Documents of Albanian History. Robert Elsie. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ↑ Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih slavena. 1930. p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Karadžić. Vol. 2–4. Štamparija Mate Jovanovnića Beograd. 1900. p. 74.

Дрногорци су пристали уз Турке против Клемената и њихових савезника Врћана20), а седамдесет и две године касније, 1685. год., СулеЈман паша Бушатлија успео је да продре на Цетиње само уз припо- моћ Брђана, који су били у завади с Црногорцима.*7! То исто догодило се 1692. год., кад је Сулејман-пагаа поново изишао на Цетиње, те одатле одагнао Млечиће и умирио Црну Гору, коЈ"а је била пристала под заштиту млетачке републике.*8) 0 вери Бр- ђани су мало водили рачуна, да не нападају на своје саплеме- нике, јер им је плен био главна сврха. Од клементашких пак напада нарочито највише су патили Плаво, Гусиње и православнн живаљ у тим крајевима. Горе сам напоменуо да су се ови спуштали и у пећки крај,и тамо су били толико силни, да су им поједина села и паланке морали плаћати данак.

- ↑ Zapisi. Vol. 13. Cetinjsko istorijsko društvo. 1940. p. 15.

Марта мјесеца 1688 напао је Сулејман-паша на Куче

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: a short history. Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ Grothusen 1984, p. 146. "popoli quasi tutti latini, e di lingua Albanese e Dalmata ... dalmatinisch, d.h. slawisch und ortodox"

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 33.

- ↑ Mita Kostić, "Ustanak Srba i Arbanasa u staroj Srbiji protivu Turaka 1737-1739. i seoba u Ugarsku", Glasnik Skopskog naučnog društva 7-8, Skoplje 1929, pp. 225, 230, 234

- ↑ Albanische Geschichte: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung, p. 239 (in German)

- ↑ Borislav Jankulov (2003). Pregled kolonizacije Vojvodine u XVIII i XIX veku. Novi Sad - Pančevo: Matica Srpska. p. 61.

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 27.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Pearson 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Südost Forschungen, Vol 59-60, p. 149, (in German)

- ↑ Ndue Bacaj (Gazeta "Malësia") (March 2001), Prek Cali thërret: Rrnoftë Shqipnia, poshtë komunizmi (in Albanian), Shkoder.net, archived from the original on 2013-12-24, retrieved 2013-12-25

- 1 2 Luigj Martini (2005). Prek Cali, Kelmendi dhe kelmendasit (in Albanian). Camaj-Pipaj. p. 66. ISBN 9789994334070.

- ↑ Elsie 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 31. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ Petrović 1941, p. 112.

- ↑ Petrović 1941, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Erdeljanović, Jovan (1907). Kuči - pleme u Crnoj Gori. p. 148.

- ↑ Petrović 1941, pp. 175–176, 184.

- ↑ "VOAL - Online Zëri i Shqiptarëve - PAIONËT E VARDARIT I GJEJMË KELMENDAS NË LUGINËN E DRINITShtegëtimi i paionëve nga liqeni i Shkodrës në luginën e VardaritNga RAMIZ LUSHAJ". www.voal-online.ch.

Sources

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78453-401-1.

- Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: a reader of historical texts, 11th-17th centuries. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04783-8. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture. C. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Grothusen, Klaus Detlev (1984). Jugoslawien: Integrationsprobleme in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Beitr̈age des Südosteuropa-Arbeitskreises der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft zum V. Internationalen Südosteuropa-Kongress der Association internationale d'études du Sud-Est européen, Belgrad, 11.-17. September 1984 [Yugoslavia: Integration Problems in the Past and Present: Proposal of the South-East Europe Working Group of the German Research Foundation to the Fifth International Congress on South-Eastern Europe of the Association internationale d'études du Sud-Est européen, Belgrade, 11-17 September 1984] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-27315-9.

- Hecquard, Hyacinthe (1859). "Tribu des Clementi". Histoire et description de la Haute Albanie ou Ghégarie (in French). Paris: Bertrand. pp. 175–197.

- Jovićević, Andrija (1923). Malesija. Rodoljub.

- Malcolm, Noel (2020). Rebels, Believers, Survivors : Studies in the History of the Albanians (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198857297.

- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania in the twentieth century: a history. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0.

- Petrović, Mihailo (1941). Đerdapski ribolovi u prošlosti i u sadašnjosti. Vol. 74. Izd. Zadužbine Mikh. R. Radivojeviča.

- Shkurtaj, Gjovalin (2013). E folmja e Kelmendit [The idiom of Kelmendi]. Artjon Shkurtaj. p. 23. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.

Further reading

- Wolff, Martine (2022). "Transhumance in Kelmend, Northern Albania: Traditions, Contemporary Challenges, and Sustainable Development". In Bindi, Letizia (ed.). Grazing Communities: Pastoralism on the Move and Biocultural Heritage Frictions. Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology. Vol. 29. Berghahn Books. pp. 102–120. ISBN 9781800734760.