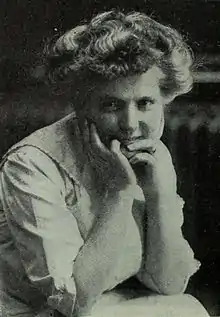

Kate Langley Bosher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Kate Lee Langley February 1, 1865 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | July 27, 1932 (aged 67) Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, suffragist |

| Spouse |

Charles Gideon Bosher

(m. 1887; died 1931) |

Kate Langley Bosher (February 1, 1865 – July 27, 1932) was an American novelist from Virginia, best known for her novels Mary Cary (1910) and Miss Gibbie Gault (1911).[1] She was also a suffragist and founding member and officer of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia.[2]

Early years, education, and marriage

Kate Langley was born in Norfolk, Virginia to Charles Henry and Portia Victoria Deming Langley in 1865. She graduated from the Norfolk College for Young Ladies in 1882.[2]

She married Richmonder Charles Gideon Bosher, a part owner of a carriage manufacturing business, on October 12, 1887. The Boshers lived in downtown Richmond before moving to Monument Avenue after World War I. The couple had no children.[2]

Writing career

Bosher was best known for writing popular fiction; her works were typically set in Virginia or in other locations in the American South and focused on the experiences of southerners after the American Civil War.[2]

Bosher's first book Bobbie (1899) was published when she lived in Richmond under the pseudonym Kate Cairns while the rest of her books were written under her real name.[2]

Her most successful novels were Miss Gibbie Gault (1911), Kitty Canary (1918), His Friend Miss McFarlane (1919), and Mary Cary, Frequently Martha (1910). Mary Cary, Frequently Martha was the most popular, selling over 100,000 copies within a year of release. It was the only one of Bosher's novels to have a film adaptation. Mary Cary, Frequently Martha was received well by readers as soon as it was written. Readers of the novel love the story of the spunky orphan Mary who navigates her unfortunate life living in an orphanage with a corrupted caregiver as she makes friends and makes the best out of a bad situation. In 1910, The Chicago Record-Herald said about the novel, “Let’s be glad for books like Mary Cary. It isn’t so much what Mary Cary does, however, as what she is, bless her! That warms the cockles of the chilliest, most snugly corseted heart.”[3]

Mary Cary was adapted to film in the 1921 silent feature Nobody's Kid starring Mae Marsh (as Mary), Kathleen Kirkham, and Anne Schaefer, and directed by Howard Hickman.

The 2006 reference work Southern Writers: A New Biographical Dictionary describes Bosher's work as "sentimental and romantic; her characters are lively and their adventures amusing."[4]

Additionally, Bosher contributed short stories to newspapers and magazines.[2]

Women's suffrage advocacy

Bosher believed that women had earned the right to vote as taxpayers and citizens. She believed women deserved to be able to vote for what they wanted rather than to rely on men to vote on their behalf or in their interest. In Bosher's eyes, women were responsible for the health and education for their families and should be able to vote on things that affected these responsibilities. [2]

Bosher was an "ardent suffragist"[1] and joined forces with friend Lila Meade Valentine and others to found the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (ESL) in November 1909. She was also an officer of the ESL. That same year, Bosher wrote and the ESL published The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, a pamphlet articulating the ESL's purpose and strategy.[2]

On January 20, 1912, Bosher and others testified in the chamber of the Virginia House of Delegates before a state legislative committee on the subject of women's suffrage. On June 25, 1916, Bosher spoke about women's suffrage at the Virginia Press Association's convention in front of the governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and secretary of the navy.[2]

Bosher worked hard to ensure women got the right to vote, and when, after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the ESL disbanded, she reorganized it as the Virginia League of Women Voters;[5] Bosher chaired the new organization's child welfare committee.[2]

Other advocacy work

Bosher was actively involved in relief work during World War I, and also worked for orphans' welfare.[1]

In 1916, Virginia's governor appointed Bosher to the board of the Virginia Home and Industrial School for Girls, a reform school for girls. She was reappointed in 1922.[2]

Bosher was also a member of the Richmond Education Association and a founding member and two-term president (1922 and 1923) of the Woman's Club of Richmond.[2]

Death

Bosher died in Norfolk on July 27, 1932, less than a year after her husband, and was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.[2]

Selected works

- Bobbie (1899) (under pseudonym Kate Cairns)

- When Love Is Love (1904)[6]

- Mary Cary, Frequently Martha (1910)

- Miss Gibbie Gault (1911) (sequel to Mary Cary)[7]

- The House of Happiness (1912)

- The Man in Lonely Land (1913)

- How It Happened (1914)

- People Like That (1916)

- Kitty Canary (1918)

- His Friend, Miss McFarlane (1919)

References

- 1 2 3 (29 July 1932). Mrs. Kate Bosher, Author, Dies at 67; Widely Known Virginia Writer Published "Mary Cary" and "Gibbie Gault", The New York Times (Associated Press story)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gushee, Elizabeth M. "Kate Lee Langley Bosher (1865–1932)". Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ "Mary Cary, Frequently Martha". Librivox. Retrieved 27 Sep 2019.

- ↑ Flora, Joseph M. & Ambel Vogel (eds.) Southern Writers: A New Biographical Dictionary, p. 36 (2006)

- ↑ McDaid, Jennifer Davis (1 August 2019). "Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (1909–1920)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ (31 January 1904). A Glance Here and There At The Books of the Day, Richmond Times-Dispatch

- ↑ (18 July 1911). New Books By Popular Writers - Including Sequels to "Mary Cary" and "The Rose of Old St. Louis", The New York Times

External links

- Works by Kate Langley Bosher at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kate Langley Bosher at Internet Archive

- Works by Kate Langley Bosher at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Kate Langley Bosher at IMDb

- Nobody's Kid at IMDb