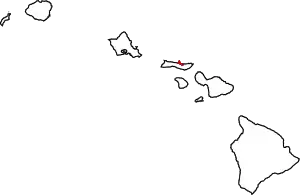

Kalaupapa | |

|---|---|

Most of the village of Kalaupapa as seen from an airplane. This photo also includes a section of the sea cliffs that form a natural barrier between the Kalaupapa Peninsula and "Topside" Molokaʻi. | |

Kalaupapa | |

| Coordinates: 21°11′22″N 156°58′54″W / 21.18944°N 156.98167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Hawaii |

| County | Kalawao |

| Elevation | 66 ft (20 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 82 |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (Hawaii-Aleutian) |

| ZIP codes | 96742 |

| GNIS feature ID | 360096[1] |

Kalaupapa (Hawaiian pronunciation: [kəlɐwˈpɐpə])[1][2] is a small unincorporated community and Hawaiian home land[3] on the island of Molokaʻi, within Kalawao County in the U.S. state of Hawaii. In 1866, during the reign of Kamehameha V, the Hawaii legislature passed a law that resulted in the designation of Molokaʻi as the site for a leper colony, where patients who were seriously affected by leprosy (also known as Hansen's disease) could be quarantined, to prevent them from infecting others.[4][5] At the time, the disease was little understood: it was believed to be highly contagious and was incurable until the advent of antibiotics. The communities where people with leprosy lived were under the administration of the Board of Health, which appointed superintendents on the island.

Kalaupapa is located on the Kalaupapa Peninsula at the base of some of the highest sea cliffs in the world, rising 2,000 feet (610 m) above the Pacific Ocean. In the 1870s a community to support the leper colony was established here. The legislature required people with severe cases to be quarantined on the island in the hope of preventing contagion.[6] The area has been preserved as the Kalaupapa National Historical Park, which takes in the entire county.

Despite the declining population, the post office is still active,[7] having a zip code of 96742.[8]

Leprosy settlement

The village is the site of a former settlement for people with leprosy. At its peak, about 1,200 men, women, and children were exiled to Kalaupapa Peninsula.[9] The isolation law was enacted by King Kamehameha V and remained in effect until its repeal in 1969. Today, about four people who formerly had leprosy continue to live there.[10] The colony is now included within Kalaupapa National Historical Park.

The original leper colony was first established in Kalawao in the east, opposite to the village corner of the peninsula. It was there where Father Damien settled in 1873. Later it was moved to the location of the current village, which was originally a Native Hawaiian fishing village. The settlement was also attended by Mother Marianne Cope and physician Arthur Albert St. Mouritz, among others. In 1893–1894, the Board of Health tried to remove the last fishing village inhabitants in order to expand the colony to encompass the entire Kalaupapa peninsula, including Kalawao.[6]

Shortly before the end of mandatory isolation in 1969, the state legislature considered closing the facility entirely. Intervention by interested persons, such as entertainer Don Ho and TV newsman Don Picken, resulted in allowing the residents who chose to do so to remain there for life. The opponents to closure pointed out that, although there were no active cases of leprosy in the colony, many of the residents were physically scarred by the disease to an extent that would make their integration into mainstream society difficult if not impossible.

In total over the decades, more than 8,500 men, women and children living throughout the Hawaiian islands and diagnosed with leprosy were exiled to the colony by the Hawaiian government and legally declared dead.[11]

Geography

The Kalaupapa Peninsula remains one of the most remote locations in Hawaii due to unique volcanic and geologic activity over millions of years.[12] Specifically, Molokai’s famous sea cliffs, which reach up to three thousand feet above sea level and are among the tallest in the world, are most responsible for restricting access. Geologists thought that these cliffs were carved by wind and water erosion, but it is now believed that they formed after a third of the northern portion of the island collapsed into the sea. The offshore islands—'Ōkala, Mōkapu, and Huelo—support this theory, housing original plant species found on Molokai over two thousand years ago such as the rare native loulu palm.[12] Mōkapu also hosts a remnant population of Emoia impar, the dark-bellied copper-striped skink, which was introduced to Hawaii more recently.

Around 230,000–300,000 years ago, an offshore shield volcano named Pu’u’uao erupted from the sea floor. The extremely hot and fast flowing pāhoehoe lava created a flat triangle of land which eventually cooled and connected to the main part of the island.[12]

Among residents' most pressing challenges to survival was the scarcity and preservation of freshwater.[13][14][15] An interest in the Kalaupapa coastal aquifer was captured by conflicting early accounts of visitors Jules Remy (1893) and Nakuino (1878) who described Kauhako Crater lake, a central geomorphic feature of the Kalaupapa peninsula as containing salt or freshwater, respectively. Kauhako lake, a freshwater resource during certain times in Kalaupapa’s history, has largest depth-to-area ratio for any lake on earth. The lake has a weak tidal connection to the ocean and the Kalaupapa peninsula is underlain by only a thin freshwater lens.[16]

Access to the Peninsula

Until the construction of the Kalaupapa Airport in 1935, the only way into the peninsula was by boat or descending down the Kalaupapa Pali trail.[17] Nowadays, accessing the peninsula via boat requires a special use permit. It is prohibited to come within 1,300 feet (400 m) of the Kalaupapa shoreline.[18]

The Kalaupapa Trail

The 3.5-mile (5.6 km) Kalaupapa Pali Trail is the only land access into Kalaupapa. The trail consists of 26 switchbacks with a 2,000-foot (610 m) elevation change over the course of the trail. The National Park Service describes the hike as extremely strenuous due to the steep, uneven surfaces and varied trail conditions.[19] Many visitors also ride Molokai mules down the trail into Kalaupapa.[20]

Trail collapse

On the evening of December 25, 2018, a postal service worker discovered significant damage to the trail from an enormous landslide. According to the Star Advertiser, the landslide took out a bridge on one of the switchbacks, and the trail is indefinitely closed.[21] There has been no report of a damage assessment, likely due to the government shutdown happening at the time. The State Department of Health's Kalaupapa administrator Kenneth Seamon says that supply deliveries shouldn’t be affected since they come via barge and plane. The barge arrives once a year in the summer, and Kamaka Air stops weekly.[21]

The Kishin Shinoyama photoshoot

In 1972, Japanese photographer Kishin Shinoyama photographed fashion-model Marie Helvin and some of her family more or less naked on the beach of Kalaupapa. These photos were edited in the book 'Marie's seven days in Molokai'. In her 2007 biography Helvin explained that, according to Japanese custom, these photos were meant to be innocent and artistic.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park

The Kalaupapa National Historical park was established December 22, 1980.[18] The park only allows 100 visitors a day and each visitor must have a sponsor; either through one of the tour companies or a resident. The National Park Service outlines several key pieces of information to know before planning a visit:

- Persons under 16 years of age are not permitted to visit Kalaupapa.[22]

- There are no medical facilities at Kalaupapa. Any emergency medical response can take hours and may require a helicopter flight to Oahu or Maui.[22]

- There are no dining or shopping facilities available in Kalaupapa. All food and sundries must be brought in and all trash taken out.[22]

- Photography of patient-residents and their property is strictly prohibited without their express written permission.[22]

- The 3.5 mi (5.6 km) trail to the park is extremely steep and challenging with uneven surfaces. Rock and mudslides on the trail are common. Hiking the trail is physically demanding and careful consideration should be given to one's physical fitness level before beginning the hike.[22]

- Overnight accommodations are available only to guests of residents.[22]

See also

- Kalaupapa National Historical Park

- Molokai: The Story of Father Damien

- Kalaupapa Peninsula and Molokai's Sea Cliffs. Aerial Interactive Images.

- Marie Helvin. The autobiography. Published in 2007 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, ISBN 978-0-297-85311-4.

References

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kalaupapa, Hawaii

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of Kalaupapa". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ https://dhhl.hawaii.gov/po/molokai/kalaupapa-nhp-nps-general-management-plan/

- ↑ Dutton, Joseph (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10.

- ↑ "Fear and Loathing in Hawaii: 'Colony'". NPR.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of Kalaupapa - Kalaupapa National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Photos of Molokai, Hawaii: An unspoiled island for adventurous travelers". About.com Travel. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Zip Code 96742 Profile, Map and Demographics for the Week of 26 November 2016". Zipdatamaps.com.

- ↑ Bowman, Sally-Jo (December 1995). "Remembering the time of separation". National Parks. 69: 30 – via EBSCO Host.

- ↑ "A Dwindling Kalaupapa Population Honors 1st Exiles With Tributes And Tears". January 8, 2023. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023.

- ↑ "Background | Ka 'Ohana O Kalaupapa". Kalaupapa ‘Ohana. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- 1 2 3 National Park Service U. S. Department of Interior (March 23, 2016). "Geography of Kalaupapa" (PDF). NPS.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Flexner, James L. (March 1, 2012). "An Institution that was a Village: Archaeology and Social Life in the Hansen's Disease Settlement at Kalawao, Moloka'i, Hawaii". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 16 (1): 135–163. doi:10.1007/s10761-012-0171-4. ISSN 1573-7748. S2CID 254538930.

- ↑ Somers, Gary F. (1985). Kalaupapa, More Than a Leprosy Settlement: Archeology at Kalaupapa National Historical Park. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

- ↑ Oberle, Ferdinand K. J.; Cheriton, Olivia M.; Swarzenski, Peter W.; Brown, Eric K.; Storlazzi, Curt D. (February 1, 2023). "Physicochemical coastal groundwater dynamics between Kauhakō Crater lake and Kalaupapa settlement, Moloka'i, Hawai'i". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 187: 114509. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114509. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 36610300. S2CID 255502022.

- ↑ Oberle, Ferdinand K. J.; Cheriton, Olivia M.; Swarzenski, Peter W.; Brown, Eric K.; Storlazzi, Curt D. (February 1, 2023). "Physicochemical coastal groundwater dynamics between Kauhakō Crater lake and Kalaupapa settlement, Moloka'i, Hawai'i". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 187: 114509. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114509. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 36610300. S2CID 255502022.

- ↑ State of Hawaii. "KALAUPAPA AIRPORT". Hawaii Aviation.

- 1 2 National Park Service (November 5, 2018). "Kalaupapa: How To Visit Our Park". Kalaupapa National Park Service.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ National Park Service. "Trail Safety" (PDF). National Park Service.

- ↑ Kalaupapa, Mailing Address: P. O. Box 2222 7 Puahi Street; Us, HI 96742 Phone: 808 567-6802 Contact. "Directions - Kalaupapa National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Associated Press (December 31, 2018). "Kalaupapa trail closed indefinitely after landslide". The Star Advertiser.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 National Park Service (September 27, 2017). "Plan Your Visit". National Park Service Kalaupapa.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Further reading

- Jack London — "The Lepers Of Molokai"

- Brennert, Alan. Moloka‘i: A Novel. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2003. ISBN 0-312-30435-8.

- Nalaielua, Henry, with Sally-Jo Bowman. No Footprints in the Sand: A Memoir of Kalaupapa. Honolulu: Watermark, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9779143-0-2.

- Puahala, Cathrine. We Had a Life: My Years at Kalaupapa. Hilo, Hawaiʻi: Pili Productions, 2016. ISBN 978-0-9913778-3-1

- Tayman, John. The Colony: The Harrowing True Story of the Exiles of Molokai. New York: Scribner's, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-3300-X.

- The Leper, Steve Thayer 2008

- Kirby Wright. The Queen of Moloka‘i Book 1: Based On a True Story. California: Lemon Shark Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-7307661-7-6.

- Arthur Albert St. Mouritz. The Path of the Destroyer, 1916.

- Greene, Linda W. Exile in Paradise. National Park Service, 1985.

- Wade, H. W. Human Inoculation Experiments in Hawaii Including Notes On Those of Arning and Of Fitch. International Journal of Leprosy. Volume 19 Number 2, 1951.

External links

- "Fear and Loathing in Hawaii: 'Colony'" (NPR Fresh Air, February 2 2006)

- "Last days of a leper colony" (CBS News article, March 22 2003)

- Dutton, Joseph (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10.

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin obituary: "Sheriff of Kalaupapa demystified disease", February 5, 2008.

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin obituary: "Newsman thrived amid 'shenanigans", December 1, 2008.

- Pictopia.org 1667769 (26-Kalaupapa, HI-1) Plan for Proposed Lighthouse Keeper's House