| Jumpman | |

|---|---|

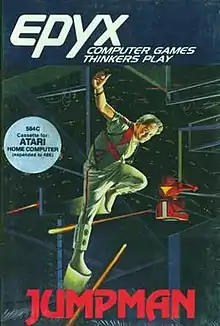

Original cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Epyx |

| Publisher(s) | Epyx |

| Designer(s) | Randy Glover[1] |

| Platform(s) | Atari 8-bit, Apple II, Commodore 64, IBM PC, ColecoVision |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Jumpman is a platform game written by Randy Glover and published by Epyx in 1983. It was first developed for the Atari 8-bit family, and versions were also released for the Commodore 64, Apple II, and IBM PC.

The game received very favorable reviews when it was released and was a major hit for its publisher, Automated Simulations. It was so successful that the company renamed itself Epyx, formerly their brand for action titles like Jumpman. Re-creations on other platforms, and new levels for the original versions, continue to appear.

Jumpman was published on diskette, but a version of the game with 12 new levels instead of 30 was released on cartridge as Jumpman Junior.[3] It was available on the Atari 8-bit computers, Commodore 64, and ColecoVision.

Gameplay

According to the story, the base on Jupiter has been sabotaged by terrorists who have placed bombs throughout the base's three buildings. The object of the game is to defuse all the bombs in a platform-filled screen. Jumpman defuses a bomb by touching it. Jumpman can jump, climb up and down ladders, and there are two kinds of rope each allowing a single direction of climbing only.

The game map is organized into a series of levels, representing the floors in three buildings. When all of the bombs on a level have been deactivated, the map scrolls vertically to show another floor of the building. When all of the levels in a building are complete, a screen shows the remaining buildings and moves onto the next one. The order of the maps is randomized so players do not end up trapped on a level they cannot complete.

Hazards include falling "smart darts" (small bullets that fly slowly across the screen, but when orthogonally lined up with Jumpman, greatly speed up and shoot straight in his direction), fall damage, and other hazards that are unique to a certain level. Upon being hit or falling from a height, Jumpman tumbles down to the bottom of the screen, with a measure from Chopin's Funeral March being played.

Points are awarded for each bomb defused, with bonus points available for completing a level quickly. Jumpman's game run-speed can be chosen by the player, with faster speeds being riskier but providing greater opportunity to earn bonus points.

Development

Randy Glover was living in Foster City, California and had been experimenting with electronics when he saw his first computer in 1977 when he played Star Trek at a Berkeley university open house.[4] This prompted him to purchase a Commodore PET in 1978[5][lower-alpha 1] and then upgrade to a TRS-80 due to its support of a hard drive.[6]

Jumpman came about after Glover saw Donkey Kong[7][8] in a local Pizza Hut.[9] This led him to become interested in making a version for home computers. He visited a local computer store who had the TI-99/4A and Atari 400. He initially purchased the TI-99 due to its better keyboard,[10] but when he learned the graphics were based on character set manipulation, he returned it the next day and purchased the Atari.[11]

The initial version was written by Albert Persinger, using a compiler on the Apple II, moving the software to the Atari. A prototype with 13 levels took four or five months to complete. After looking in the back of a computer magazine for publisher, in early 1983 he approached Broderbund.[12] They were interested but demanded that their programmers be allowed to work on it. The next day he met with Automated Simulations, who were much more excited by the game and agreed to allow Glover to complete it himself.[13]

At the time, the company was in the process of moving from the strategy game market to action titles, which they released under their Epyx brand. Jumpman was the perfect title for the brand, and the company hired him.[14] Aiming the game at the newly enlarged RAM available on the Atari 800 led to the 32 levels of the final design.[15] The Atari release was a huge hit, and the company soon abandoned their strategic games and renamed as Epyx.[16] Glover then moved on to a C64 port, which was not trivial due to a particular feature of the Atari hardware Glover used to ease development.[17]

Other programmers at Epyx ported it to the Apple II, with poor results,[18] and, a year later, contracted Mirror Images Software for an IBM PC/PCjr port. The Atari and Commodore versions were released on disk and cassette tape, the Apple and IBM versions only on disk. The Atari version used a classic bad-sector method of preventing copying, but this had little effect on piracy.[19]

After developing the original versions, Glover moved on to Jumpman Junior, a cartridge title with only 12 levels. He stated that it wasn't really a sequel to Jumpman, but more of a "lite" version for Atari and Commodore users who didn't have disk drives. These versions removed the more complex levels and any code needed to run them.[20] Two of its levels (Dumbwaiter and Electroshock Traps) were turned into Sreddal ("Ladders" backwards) and Fire! Fire! on the latter. The C64 version was later ported to the ColecoVision, which used the C64 levels.[21]

Glover continued working at Epyx, working on the little-known Lunar Outpost and the swimming section of Summer Games. He remained at the company for about two years[22] before returning to the cash register business.[23]

Technical details

Movement was controlled through the collision detection system of the Atari's player/missile graphics hardware. This system looks for overlap between the sprites and the background, setting registers that indicate which sprite had touched which color.[24]

Glover separated the Jumpman sprite into two parts, the body and the feet. By examining which of these collided, the engine could determine which direction to move. For instance, if both the body and feet collided with the same color, it must be a wall, and the Jumpman should stop moving. If there was no collision with either his feet or body, Jumpman is unsupported and should fall down the screen. Variations on these allowed support for ramps, ropes, and other features.[25]

This not only saved processing time comparing the player location to an in-memory description of the map, but also meant that maps could be created simply by drawing with them and experimenting with the results in the game.[26]

Reception

Jumpman became a best-seller for Epyx, selling about 40,000 copies on the Atari and C64 until 1987,[27] reaching somewhere between #3 and #6 on the then-current Billboard top 100 games chart.[28][29] Sales were hindered by the release of Miner 2049er only a few months earlier, which held the #1 spot at that time.[30]

Softline in 1983 liked Jumpman, calling it "wonderfully addicting" and stating that it was as high-quality as Epyx's Dunjonquest games. The magazine cited its large number of levels ("Not one screen faster and harder each time; not ten screens three times; but thirty screens, one at a time"), and concluded that "it's bound to be a hit".[31] Compute! awarded it a lengthy review. They point out that it might be dismissed as yet another platform game, but goes on to state that "Jumpman easily conquers that skepticism and establishes itself as a software classic." They also note the variety of clever level designs that makes each map unique. They go on to compare it to Miner 2049er and suggested Jumpman is "much, much more."[32]

In 1984 Softline readers named the game the seventh most-popular Atari program of 1983,[33] and it received a Certificate of Merit in the category of "1984 Best Computer Action Game" at the 5th annual Arkie Awards.[34]: 28

K-Power rated the Commodore 64 version of Jumpman 7 points out of 10. The magazine stated that the game "has very good—not great—graphics, color, and sound. But because it's so enjoyable to play, it will be a long time before it's put away."[35] Stating that "the care that goes into its products is obvious in Jumpman", The Commodore 64 Home Companion wrote that "it's really 30 games in one, with seemingly endless variants on the simple jumping theme to keep you interested".[36]

Legacy

In 1998, Randy Glover became aware of the many fans of Jumpman and started working on Jumpman II, keeping a development diary at the now defunct jumpman2.com site. The last recorded diary entry was made in 2001.[37]

In 2008, the original Jumpman was released on the Wii's Virtual Console.[38]

In 2014, Midnight Ryder Technologies shipped Jumpman Forever[39] for the OUYA micro-console, with planned releases for PC, Mac, iOS, and Android platforms. Originally titled Jumpman: 2049, the game is considered to be an official sequel based on rights given to Midnight Ryder Technologies [40] back in 2000 by Randy Glover.

In 2018 Jumpman was re-released on THEC64 Mini as one of the 64 built in games. A game called Jumpman 2 was also on the machine, but in reality is just Jumpman Junior rebranded.

Unofficial ports and fan remakes

In 1991, Jumpman Lives! was released by Apogee Software. The game consists of four "episodes", each with twelve levels: the first is free, the rest for sale. The game contains levels from Jumpman and Jumpman Junior, new levels, and a level editor. Apogee withdrew the game soon after release at the request of Epyx, who owned the rights to Jumpman at the time.[41]

In 1994, an unofficial MS-DOS port of Jumpman, missing the level "Freeze", was released by Ingenieurbüro Franke.[42] An updated version which included Freeze was released in 2001.

In 2003, The Jumpman Project, an MS-DOS version of the game that can be run under Microsoft Windows, was released.[43]

See also

- Miner 2049er (1982)

- Lode Runner (1983)

- Mr. Robot and His Robot Factory (1984)

- Ultimate Wizard (1984)

Notes

- ↑ Glover refers to this as a VIC-20, but this was not introduced until some years later.

References

- ↑ Hague, James. "The Giant List of Classic Game Programmers".

- ↑ "Jumpman (Registration Number TX0001337562)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Faughn, David (March 1984). "Jumpman Junior". Antic. 2 (12): 100.

- ↑ Glover, 3:00.

- ↑ Glover, 4:00.

- ↑ Glover, 5:00.

- ↑ Guenther, Darryl (Fall 1999). "Doin' the Donkey Kong" (PDF). Classic Gamer Magazine: 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ↑ "I talked to Randy Glover about Jumpman". Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ↑ Glover, 10:30.

- ↑ Glover, 12:30.

- ↑ Glover, 11:30.

- ↑ Glover, 14:00.

- ↑ Glover, 15:00.

- ↑ Glover, 15:45.

- ↑ Glover, 18:00.

- ↑ "Epyx Journey". The Dot Eaters.

- ↑ Glover, 48:45.

- ↑ Glover, 52:15.

- ↑ Glover, 39:30.

- ↑ Glover, 48:00.

- ↑ Glover, 53:00.

- ↑ Glover, 49:00.

- ↑ Glover, 1:06:00.

- ↑ Crawford, Chris (1982). "Hardware Collision Detection". De Re Atari. Atari Program Exchange.

- ↑ Glover, 20:00.

- ↑ Glover, 22:00.

- ↑ Glover, 36:15.

- ↑ Glover, 37:00.

- ↑ Glover, 1:12:15.

- ↑ Glover, 38:00.

- ↑ Yuen, Matt (May–Jun 1983). "Jumpman". Softline. p. 45. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Trunzo, James (October 1983). "Jumpman". Compute!: 150.

- ↑ "The Best and the Rest". St.Game. Mar–Apr 1984. p. 49. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (February 1984). "Arcade Alley: The 1984 Arcade Awards, Part II". Video. Reese Communications. 7 (11): 28–29. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ↑ Schussheim, Adam (February 1984). "Jumpman". K-Power. p. 61. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ Beekman, George (1984). "Epyx Software". The Commodore 64 Home Companion. p. 170-171. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ↑ "OLD NEWS". Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ "Jumpman". Nintendo UK.

- ↑ Kickstarter-based Jumpman Forever Ships This Week on Wichita Business Journal website

- ↑ The History of Jumpman (and Jumpman Forever) Archived 2014-05-20 at the Wayback Machine On JumpmanForever.com

- ↑ "DAVE SHARPLESS INTERVIEW". Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ↑ Classic Jumpman

- ↑ The Jumpman Project

Bibliography

- Randy Glover, Kevin Savetz, Rob McMullen (12 May 2016). ANTIC Interview 171 - Randy Glover, Jumpman. Antic Podcast.

External links

- Jumpman at Atari Mania

- Jumpman at Lemon 64

- Jumpman can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive